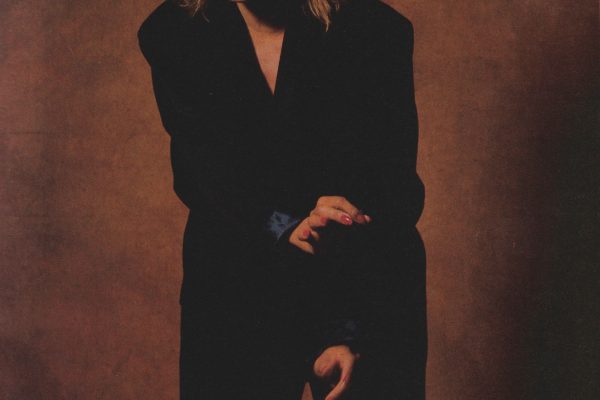

In approaching her death from AIDS, Tina Chow found the sense of mission that had eluded her in her years as the stylish enchantress who reigned over the beau monde in-spot restaurants she created with her then husband, Michael Chow. As MAUREEN ORTH reports, Tina fought the disease and its preconceptions–especially the lack of respect for women with AIDS — with her unerring grace, making her death her most bravely beautiful statement.

Shortly after the memorial service for Tina Chow in Los Angeles on Valentine’s Day, her family who had been a model of selfless devotion through her long struggle with AIDS, gathered to discuss whether they couldn’t have done yet more to help her. Had they been right, they asked themselves to let her reject conventional treatment and battle the disease in her own way, without AZT? However agonizing it had been for them to see their beautiful Tina suffering so, especially with the added disadvantage of being a woman with the disease, Tina’s sister, Adelle, known as Bonny concluded that the answer was yes. “I told my parents what I felt when I was sitting alone one night getting anxious about missing Tina and then suddenly feeling this great warmth around me, and what I felt she was saying. It was ‘Our choices, are our own.’ ”

By the end, the once glamorous and often imitated Tina Chow had had it with chic thrills. In battling AIDS, she recreated herself, from passive to aggressive from enabler to achiever. She retreated totally from her earlier, gilded life in London and New York to the rugged California coastline, and in the last year she began to sculpt in wood. According to Bonny, the act of creation was the one thing “that transformed and enlivened her.”

Her family had respected her choices because they understood that Tina’s transformation would give the meaning to her life that she desired, “We were raised in this Asian way, in that we’re not really adept at expressing our feelings and our rights,” says Bonny. “The most important thing to Tina was that she learned to be honest and much more open with everyone, across the board.”

Tina Chow’s story is the classic woman’s tale of the struggle to define herself–in her case, beyond the social world in which she dazzled so effortlessly, beyond her former husband’s image of her, beyond the satisfaction of being a fabulous clothes hanger for others’ creations. It’s about going from The Look to The Work. That she succeeded in the end was expressed by her brother-in-law, David Byrne, in the words of a song he wrote and sang at the Valentine’s Day memorial:

Runnin naked like the day when I was born

They’re all naked in the land where I come from

I’m a long, long way from New York City now.

We’re all naked if you turn us inside out.

Tina never thought she was beautiful, but she was the one everyone came to see. Mick would be there with Bianca back then, and Jerry Hall with Bryan Ferry. There was Issey Miyake on the left. Karl Lagerfield on the right. David Hockney, Manolo Blahnik. David Bailey, Joan Collins, Peter O’Toole, Bernardo Bertolucci, Lauren Bacall. Mr. Chow in London in the seventies was a glamorous bath of the visual hip-snob elite—artists, designers, photographers, models, all crunching on green-black seaweed as the champagne flowed. The nouvelle Chinese cuisine was superb the presentation by the Italian waiters flawless. Michael Chow had anticipated this new era of chichi restaurants that replaced the Old Guard’s private clubs: he had envisioned the Environment. People kept his menus as pieces of art.

You went to Mr. Chow to show off or to check out who was in town from everywhere that mattered. But what kept you coming back, night after night, year after year for almost a decade, was the aura of Tina Chow.

Tina Chow, Tina Chow, Tina Chow, whispered the slaves of style in her heady wake. What’s she wearing, where’s she going, who’s she talking to? When it came to taste, she was like DiMaggio at the plate or Marilyn on a subway grate-she knew she had it, and there was nothing she could do about it.

From the moment one passed through the glass doors with the tiny TORA TORA TORA engraved at eye level so that no one would crash into them by mistake, and ascended the spiral staircase, Tina Chow’s ineffable presence was immediately felt. “When she brought you upstairs or sat with you for a moment, it was like entering heaven.” says the artist Peter Schlesinger. “In those carefree days she was beautiful, fun, the center of everything,” adds Lagerfeld. If you were a star, there’d be a star by your name on the reservations list; if you were a friend, a heart.

Tina Chow was known for both her star quality and her heart; she was an unjaded, upbeat, enthusiastic half Japanese, half-American jewel set loose among mannered aesthetes. They worshiped her androgynous angularity. “She wasn’t like a woman, but an objet dressed,” says the fashionable London decorator Nicky Haslam. “Tina did have a depth of subtlety, but she was very, very simple at heart and rather dazzled by it all. She was very sure of her taste, but not sure of herself.”

Indeed, in those days one might even catch Bettina Louise Lutz Chow, daughter of an Ohio soldier and a Japanese war bride, glancing over at her husband for encouragement. Michael Chow, twelve years her senior, was not only an exacting impresario and connoisseur collector of Art Deco furniture but also the son of a Chinese theatrical legend. He had forged an ace team: he conceptualized, his wife executed. As she once said her job was “to keep the party going.” And nobody did it better: after Mr. Chow conquered London in the late sixties and early seventies, there was Mr. Chow in Los Angeles in the mid-seventies, and then Mr. Chow in New York in the late seventies and early eighties. There were Jackie O and John Lennon and Andy Warhol, Jack and Anjelica, the Beach Boys, and Francis Coppola. And always there was Tina Chow, rising at dawn to buy the flowers she put together so dramatically for the restaurant she had closed very late the night before, and somehow trying to mother her daughter and son at the same time.

As the years passed, the degree of control exercised by Michael and the self-imposed standards of chic perfection demanded by the Chows’ way of life took their toll on the marriage and by 1987 friends saw that Tina was trying to fill the void, reaching for an identity of her own. Yet she was still the dutiful partner, helping to supervise the restaurants. And she still cross-pollinated the fashion landscape just by dripping simplicity and elegance. She was a Gap ad, she was a Saint Laurent campaign – there was nothing in between. Every time she alighted in a fashion capital, the world’s greatest celebrity photographers lined up to take her portrait. Cecil Heaton, Helmut Newton, Richard Avedon, Snowden, Robert Mapplethorpe, Steven Meisel, Herb Ritts Tina Chow sat for all of them. “There are very few women who have quite the elegance, the taste, that she had,” says Helmut Newton. But for all of that, the polished femme du monde retained a kind of girlish vulnerability. Perhaps that was why, when Tina Chow died of AIDS in January, her mourners felt not only shock and profound grief but a sense too, that there was something hopelessly incongruous about the way her life had been torn from her.

Her family’s decision to reveal the cause of death made Tina Chow the most celebrated female to date to have succumbed to AIDS. But her friends will remember her as, among other things, the woman who would stroll down Fifty-seventh Street with antique silk flowers pinned casually to her severely cut jacket only to find the same look copied in all the best stores a few weeks later. After all, with her little shells under man-tailored suits and flats, she pioneered what became known as the Armani look. A few years ago she began glomping masses of chains and crystals around her neck. Soon a clothing store in New York’s SoHo featured in its window a vintage jacket hung with necklaces and a sign that said HOMAGE A TINA CHOW. Now hordes of young men in London and New York wake up, pomade their short-cropped hair, throw on her signature uniform of pressed white T, cashmere cardigan, and narrow slacks, and declare, “Today I’m Tina Chow!”

Officially, her legacy is being commemorated at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York in its latest exhibition, “Flair: Fashion Collected by Tina Chow.” A book of the same title is being published by Rizzoli in conjunction with the exhibition. But by the time the book was under way Tina had tired of gilding the lily and was moving away from accumulation becoming motivated instead by a nascent self-awareness perhaps reinforced by the precarious state of her health. For a decade she had struggled to assert her own presence within the magnetic force field of Michael Chow. Over the last few years she had begun crafting jewelry for some of the exclusive stores that tracked her every fashion statement, as well as developing New Age aromatic massage oils and sculpting in crystals and wood.

But the sad irony of it all was that before she was forty Tina Chow had basically run out of time. In June of 1989, five months before her divorce from Michael Chow became final, Tina Chow learned that she had full-blown AIDS.

“I can’t breathe,” she told her boyfriend the film producer Richard Roth, just before getting on a plane for Japan. When the gem dealer and jewelry designer John Reinhold, who was staying in the same Tokyo hotel as Chow called her, Tina said she couldn’t see him—-she had a bad cold or maybe the flu. “I had just seen her for lunch in L.A. the week before and she had looked extraordinarily well,” says Reinhold. “Tina was always so energetic that it wasn’t unlike her to travel if she didn’t feel well.”

Her illness quickly turned into severe pneumonia, and Tina went into the hospital, where she was given a battery of tests that produced the stunning news. No one close to her remembers any earlier warning signs of the illness, a story that is fairly common among women with AIDS. “During the first three to five years after infection, women often get vague symptoms – fevers, vaginal yeast infections, diarrhea, skin rashes, sinusitis, subtle kinds of things,” says Dr. Patricia Kloser, medical director for AIDS Services at the University Hospital of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey and a pioneer of AIDS care for women. “Early symptoms can quite easily be blamed on everything from traveling under stress to New York weather.”

According to Michael Chow, Tina was infected with the AIDS virus four years earlier, in late 1985. She contracted it from the handsome and wellborn bisexual French playboy Kim D’Estainvillle, who had been linked with the beautiful and the powerful of both sexes on at least two continents –“a walker who screwed them all,” according to one less than charitable description. D’Estainville’s long-running affair with Helene Rochas, one of Paris’s leading socialites, ended, the story goes, when she picked up the telephone extension one day and overheard a torrid conversation her lover was having with one of her best friends-a man who is among France’s leading cultural czars. D’Estainville died of AIDS just after Christmas 1990.

At least one friend had warned Tina at the time that D’Estainville might be a high-risk partner. But when Tina told D’Estainville what was being said about him, he became infuriated. “I was naughty,” Tina later told Jun Kanai, who runs Issey Miyake’s U.S. operations and is helping curate Chow’s fashion exhibition for the Kyoto Costume Institute. “I only slept with this man a few times and I got it, so this should be a warning.”

Tina Chow’s sexual experience was, by all accounts, limited. “Tina was not the kind of person to pass from one bed TO another,” says her close friend the photographer Eric Boman. But there was a moment when cosmopolitan Tina would melt from hot pursuit, a romantic who appeared to believe in fairy tales.

She grew up in the suburbs of Cleveland and attended Lutheran and public schools; she was a very well behaved girl who raced to keep up with her slightly older tomboy sister, Bonny. The family was so wholesome–her father had studied for the Lutheran ministry before he found his true vocation, importing and collecting bamboo objects—that the State Department featured Walter and Mona Lutz and their two baby girls in a propaganda film shown in Japan, titled A Japanese War Bride in America. “Bay Village, Ohio, was very Leave it to Beaver,” says Bonny Lutz, who is married to the musician and producer David Byrne. “We really did grow up in the perfect small-town suburb.

There was almost no consciousness, Bonny says, that theirs was an interracial family. “We ate sushi–about the only thing I remember is that we learned early not to tell our friends about eating raw fish. We were very integrated, and our mother’s level of refinement was so high that when our friends came over we were not allowed to eat potato chips out of the bag. We had to put them into a lacquer bowl and serve them. The close-knit Lutzes also adhered to a family dynamic that stressed traditional Oriental reserve. “We weren’t Italian–we didn’t discuss things. ”

Tina may have been shy – Bonny can’t remember that she ever had a date in high school – but there are indications she was aware of style. “When the Twiggy look came out, Tina was the first one sent home because her skirt didn’t touch the floor when she was kneeling. She begged me to cut her hair like Twiggy, but I wouldn’t. She did it herself and came out looking like one of the Three Stooges.”

In 1966, when Tina was a junior in high school, the family moved to Japan so that Mona Lutz could be with her family, the girls could learn that side of their cultural heritage, and Walter Lutz could pursue his passion; his job representing Helena Rubenstein products to U.S. Army PXs was just an excuse to hunt for bamboo.

It wasn’t long before the two sisters followed the lead of others in their high school for naval dependents and started modeling. Under their mother’s agenting, they became such a hit that Tina gave up on Tokyo’s Jesuit Sophia University after just six months. Shiseido cosmetics put both girls under contract. “Tina and Bonny were the first Eurasian model to be hot in Japan in the sixties,” says Jun Kanai. “Their faces were all over, an every cover.” Suddenly Tina was no longer tagging along as the litt1e sister. “Japan was her chance to be her own person,” says Bonny, “and we kind of traded places.”

“I loved being there,” Tina Chow once told Harpers & Queen “I didn’t realize then that I was a cross-breed.” But after four successful years of posing for Shiseido and doing runway modeling for Matsuda and Issey Miyake, supermodel Tina Lutz came to the conclusion that things weren’t quite so idyllic after all. Commercial success did not mean cultural acceptance: “Gradually I found out this terrible thing–that they don’t want half-breeds in Japan, not in fashion shows or anywhere. And when I knew that, I wanted to get out.”

Enter Michael Chow. The first person to tout her future husband to twenty-year-old Tina was the late fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez, who came to Tokyo to draw for a department store. “You have to meet Michael—he’s perfect for you,” Lopez decreed. When the two somehow missed connections as Michael passed through Tokyo, Lopez fumed at her, “I can’t believe you blew it.” Another chance presented itself about a year later, in 1971, when Michael reappeared under the guise of casting for a martial-arts film he was interested in directing, and met the Lutz sisters through a mutual friend, designer Zandra Rhodes. The girls were completely bowled over. “Both of us went ‘Wow!’ ” Bonny remembers. “He was adorable, just beautiful, with long blunt-cut hair parted in the middle. And so funny.” Was it love at first sight? “Yes, one of those,” Michael Chow says today, adding cryptically, “and the rest is history.”

By the time he met Tina, Michael had studied architecture, struggled as a painter, played bit roles in movies, become the proprietor of a go-go hairdressing salon, met and married three other wives –one for just a few days–owned four restaurants and a nightclub, and was on his way to becoming a millionaire. But then Michael Chow was descended from an adventurer: his great-grandfather was a Scotsman who may have dealt in tea or opium in China-whichever, he made a pot of money. His granddaughter, Michael’s mother, was a privileged and proper young woman whose feet were not bound and who was given a Western education. She scandalized her family by running off with Michael’s father, Zhou Xinfang, a matinee idol of the Peking Opera in Shanghai who happened to be already married with three children. The couple settled in Shanghai and had three daughters before Zhou was divorced. Michael was the pampered second son in a very exalted and elite household. At one point after the Communist revolution, his father, who had become China’s greatest classical actor, was said to be the highest paid man in all of China. Zhou Xinfang wrote more than a hundred plays for the theater company he directed. His prestige was such that he was declared one of China’s eight national treasures.

Michael wanted to be an actor, but his mother had other plans for him: in 1952, when be was only thirteen, he was sent to England along with his sister Tsai Chin. She studied at London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (later gaining theatrical fame in the role of Suzie Wong), and he was put in boarding school. Except for one visit his mother made in 1961 Michael Chow never saw his parents again.

Only much later would he learn that during the Cultural Revolution they were beaten and tortured almost daily. His father spent a year in prison; by the time be was released, his once proud and vivacious wife, who had been made to sweep the streets was dead. Zhou’s books were burned; the family lost everything, Michael’s brother, William, who had followed in their father’s footsteps to become an actor with the Peking Opera, spent five years in jail. “I’ll never forget when Michael found out,” says Bonny Lutz. “He just paced up and down the room repeating, “My brother. William, spent five years in jail, my brother William spent five yean in jail.’” Today Michael Chow simply says, “I am a professional refugee.”

“He realized instinctively,” his sister Tsai Chin wrote in her absorbing autobiography, Daughter of Shanghai, “that success meant media exposure and that exposure was most easily found by associating himself with the glamorous world that newspapers and magazines depended on for copy: the world of theatre, film, society pop and such.”

“I never meant it as a business—I wanted to create a happening,” he says of the namesake venture he launched in London in 1968. The cynic in him said, “Chinese in the West can only do laundry or restaurants”; the entrepreneur said, “I want to communicate between East and West.” The timing was perfect. London’s culture quake — Mary Quant, the Beatles, the Stones – was forged by middle and working class kids who had no trouble admitting a Chinese immigrant into their midst. They needed a club, and Mr. Chow was just as innovative in its milieu as Carnaby Street was in fashion. It functioned as a stage set, like Rick’s place in Casablanca, and Michael traded food for art by the likes of Jim Dine and Richard Smith. Moreover, the total package couldn’t be copied. “The kitchen was Chinese, the waiters were Italian, and I was the only one who could communicate with both,” says Michael “I adopted the idea of British colonialism divide and rule.”

In his personal conquests, Michael was equally driven. He knew what he wanted, and he pushed pretty hard. He had gotten his previous wife, Grace Coddington, then of British Vogue to marry him by sending out hundreds of wedding invitations without her knowing a thing about it. Now Michael couldn’t wait to join the sweetly innocent Lutzes. “Our family was so important to him because he couldn’t reach his own,” says Bonny.

It wasn’t long before Tina, wide-eyed and eager but already in possession of a superior and quirky elegance, joined him in London to begin a life of serious glamour. They married in 1973 and celebrated at Mr. Chow, where Bianca Jagger upstaged the blushing bride by arriving late with nine-year-old Tatum O’Neal, both decked out in white dresses and wide-brimmed hats and carrying walking sticks. The bride was twenty-three – “but she was younger,” says Michael Chow, “It you know what I mean.”

The newlyweds flew to Los Angeles, where Jerry Moss, the M of A&M Records was backing a Mr. Chow in Beverly Hills. It was says Michael, “the first designer restaurant, light-years ahead,” in a locale that still mostly knew only from red checked tablecloths and Chianti-bottle candlesticks. Clint Eastwood showed up at the opening. Moss brought in the pop stars. The British expatriate directors of Hollywood–Alan Parker, Adrian Lyne, Ridley Scott—soon found a new home. Billy Wilder, Neil Simon, and Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw dropped in on Sunday nights, Anjelica Huston and Tina discovered they wore the same Shiseido perfume. Tina on her first trip to California, was suddenly in the thick of Hollywood. “She was kind of like teenager about it,” says Nadia Ghaleb, Tina’s closest girlfriend.

How could anyone be so adorable? “People used to go a lot just to see her–it was like her starring role,” says Peter Schlesinger. “She was chic and beautiful, always smiling and cheerful. She was a wonderful greeter and made everybody feel they were her best friend – and because she was so glamorous it made you feel just great.” If she didn’t care for you, you’d never know it. “She would give a big hello, then come back and sigh. ‘Oh, God,’ says Schlesinger, “But nothing more. She had that Oriental side—this great mask.”

“She was holding court and serving you at the same time,” says Nadia Ghaleb. “She was like the enchanted girl–nothing Tina ever did didn’t get reviewed well. The restaurants didn’t necessarily always get well reviewed, but Tina always got well reviewed.”

Michael was a tough taskmaster—several people who worked tor him referred to him as a “benevolent dictator.” His sister Tsai Chin tried to work for him in the Los Angeles restaurant as “the family representative” and quit after six months. “Michael had worked extremely hard for his success and was under enormous pressure,” she; wrote in her memoir. “He ran a tight ship and expected absolute obedience from his staff, which he always got. With me he acted the tyrannical patriarch and even outside working hours he wanted utter control over my life. The male chauvinist pig was stuck with a female one.”

Tina, of course, did not rebel. “She was unbelievably subservient,” says a friend from the early days. “Basically she had his identity,” says Grace Coddington, who remained friendly with them both. “You have to be someone, but you can’t be someone.” But even with two children—China was born in 1974 and Maximillian in 1978—Tina was just as determined as Michael to make the business a success; at one point he was the proprietor of seven different restaurants and clubs in London. If business was off at lunch, “Tina would get on the phone and get Jerry Hall to come in. She was always arranging parties, but the parties took place at Mr. Chow.” There were also plenty of hangers-on who knew that good-hearted and generous Tina was a soft touch – dozens ate for free. “A lot of those people she fed for years deserted her in the end,” says Mark Walsh, a·vintage couture dealer with whom she worked closely for a decade. “She really felt bad about that.”

Michael and Tina never spent money on fancy cars or country houses, choosing instead a luxuriously austere lifestyle, a very elevated “less is more.” In the mid-seventies they settled into a town house on Clancarty Road with a moon gate leading into the dining room and one of the few swimming pools in central London. Each object was meant to radiate form. From his childhood Michael had always been an avid collector. Now he was commissioning portraits of himself and gathering important pieces of Art Deco furniture, but all sorts of objects held fascination for him. “It’s not like today, when everybody knows something,” he says. “In those days only three people knew Montblanc pens were chic.

The writer Marie Brenner remembers Tina vividly during the early years of the marriage: “She was a very innocent, very fragile girl moving through these beautiful rooms explaining every piece of furniture, and I’m thinking, There is something about putting this girl in this atmosphere that will ultimately do her in.” Others saw nothing more sinister than and echo of Pygmalion. “Michael made her, taught her taste, but what was nice about Tina was that she was very down-to-earth,” says Jun Kanai.

“She had innate good taste,” Michael acknowledges. “I think it was master teacher, but I didn’t feel aware of it. My sister did remind me the other day that when she first met us, when she asked a question of Tina, Tina looked at me first.” Yet he remembers that “at that age Tina already had a very good eye.” Indeed, says Nadia Ghaleb, “Tina’s eye was bulletproof –with objects, furniture, clothes, jewelry. Michael has great spontaneous instincts; she was the editor.”

As time went on, there was great reverence for them as a couple. “It was always Mr. and Mrs. Chow, like they were glued together,” says New York artist Sylvia Martins. Michael was busy amassing important Art Deco, Ruhlmann and Dunand furniture made in the twenties, and Tina had taken up collecting haute couture, Fortunys and Balenciagas. The Chows were united in their fanatic visual perfectionism. “Even her handwriting looked designed,” says Peter Schlesinger. “Tina was so organized it was frightening,” says Mark Walsh. “Her closets for her collection were beyond museums.” The clothes hung in acid-free tissue and were spaced-exactly, “The word ‘style’ is really lacking here — it’s really balance, justness, and love of quality and respect for craftsmanship,” says the photographer David Seidner. “Everything Tina did was so extraordinary from the way she handled chopsticks to the way she packed her bag; everything was wrapped so beautifully, in little Japanese boxes, in perfect paper and ribbons — it was like a puzzle.”

For Tina Chow, who made the best dressed lists so many times she graduated into the B.D. Hall of Fame, all of it reflected a deeply held belief. She once told an interviewer that her mission in life was to banish ugliness. “You have either to bring beauty or ugliness,” she said, “and you’re not allowed to bring ugliness.”

In retrospect, the denouncement for the sophisticated, gilded couple, so young and rice and charmed, began when they tried to live up to the lyrics from “New York, New York”: “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere,” In 1978, when the economy in Britain appeared on the verge of collapse, Michael and Tina decided to move to America, and in a fury of work and terror they opened Mr. Chow in New York.

“New York wasn’t good for either of them,” says Nadia Ghaleb. “It was a big gamble,” Michael concedes. But the restaurant took off like a rocket. During the early eighties, in those pre-AIDS moments of glittering bisexual punk, “Mr. Chow was extremely happening,” says Paige Powell, who was then Andy Warhol’s assistant. “You could come in crazy clothes –it was Fellini-like. It definitely drew an artistic crowd. Tina was very Zenlike, regal and serene, but very alluring, very removed.”

In New York it was up to Tina to “keep the party going,” often when neither one of them felt like partying at all. Michael’s brother, William, was finally allowed to leave China for the U.S., a joyous event that proved to be fraught with hidden traumas. Michael became immersed in mounting a theatrical tribute to his father’s memory. In August 1981, actors from China led by William performed Zhou Xinfang’s plays for ten days at Lincoln Center. The engagement was widely praised, but the long-delayed grieving it stirred up in Michael brought on a brooding depression that lasted several years. “America did not work out the way Michael had hoped,” says Eric Boman. “That [reliving of history] psychologically affected me,” says Michael. “I felt racism, all kinds of stuff. After that I couldn’t communicate in New York. I lost a lot of internal power,”

Meanwhile, says Grace Coddington, “Tina had to cover up and put on a jolly face in the restaurant.” Everything was proving difficult. The Chows purchased an apartment that had once belonged to a Satanist above the restaurant on Fifty-seventh Street, and in 1982 they began a major renovation, an ordeal few Manhattan marriages survive unscathed. What Michael and Tina ended up with was a museum for their collection of Art Deco. To some it was one of the most exquisite spaces extant. Others found it funereal, the atmosphere incredibly tense. “You become a slave to this stuff,” says Mark Walsh. “You have to have the humidifier going, you have to live in complete climate control. If the kids nicked anything, it would be immediately sent out to be lacquered.

Nadia Ghaleb watched the Chows metamorphosing from a “whimsical, lighthearted twosome” who combed flea markets to “a major museum collector duo.” Michael was getting bored with restaurants, and New York wasn’t making him the toast of the town. “I think he had a chip on his shoulder about being a restaurateur,” says Boman. “He saw himself cutting a larger figure.” Meanwhile, Tina was fast becoming the darling of the downtown art moguls, a pal of bad boy Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Kenny Scharf, Julian Schnabel.

By then, Tina had more male homosexual friends–for whom she was an object of worship—than female friends. According to Grace Coddington, the gay men’s chorus, quick to size up the strains in the marriage, was forever undermining Michael. “ ‘You don’t need him,’ they’d say. ‘Look at the way he treats you. Come out with us instead.’” Michael resented them and according to Coddington, blamed them for everything that happened afterward.

“Tina at that point started to flourish,” says Michael. “She connected better. I said, ‘O.K., Tina, you have all the publicity. O.K., I’ll be Mr. Hanae Mori’” — referring to the Japanese designer whose husband runs her business. “I did it consciously.” Michael, ever more morose, disappeared from the restaurant. At one stage he spent virtually nine months in bed and gained a great deal of weight. Still, he kept tabs on everyone by watching them on the closed circuit TV he had installed. Tina, her friends say, was drinking more champagne than usual. The atmosphere between them chilled.

“When he tried to get back into the restaurant,” says Coddington, “no one knew him—it had become Tina’s restaurant. She took it on because she had to, and he wanted it back.”

“There would be dinner parties with her friends when nobody talked to him,” says Walsh. “It was very bizarre. She was so much the center of attention.”

They began to travel separately. Still, few suspected the depth of Tina’s unhappiness, because she did not confide much in those days, and she never forgot her role at the restaurant. “When she was on, she was so on,” says Walsh. “But when she was off, she was coming unglued. In a weird way Tina had no self-esteem. To some Helmut Newton’s photograph from that period, showing Tina in a Chanel gown, her wrists roped to the bar of Mr. Chow as Michael looks on warily, says it all. “That picture is their marriage,” observes Peter Schlesinger. (Nonsense, says Newton: “Anyone who knows anything about me knows how much I like to tie women up.”)

In January 1985, Michael and Tina moved to Los Angeles–definite1y Michael’s idea. He said that tending his collection in the newly done New York apartment was making him ever more obsessive and stifling his creativity. “I was a prisoner of Ruhlmann furniture. That’s what depressed people do—they go around straightening the furniture.”

But the move didn’t seem to help. “They came to L.A. and they never quite hit a groove out here,” says Jerry Moss sadly. Tina had never liked L.A. anyway, and the family ended up spending that summer back in New York. It was then that Andy Warhol started pressuring Tina to do something on her own, design a line of clothing, something. And it was then, as she was casting about for that something, that she had her fatal encounter with Kim D’Estainville during a visit to Paris.

For a long time Tina held back from beginning anything on her own. Certainly, her husband wasn’t amenable–he needed her in the restaurants. And surrounded as she was by the highest-paid and most successful pop stars of art and fashion, whatever she did had better be pretty good.

But Warhol insisted. (“He always played the evil fairy,” someone remarked.) He would phone Tina in the morning and say, “O.K., what are we doing today?” pushing her to begin. “Tina seemed so confident, and she was about her taste, but when it came to her own creativity, it took her a long time for it to come forth,” says Maggie Salamone, who helped Tina restore her vintage-couture collection. “When I found out she was sick, it was so painful, because I felt like she was finally dealing with doing something on her own.”

One day Warhol showed Tina two crystal pendants he’d been wearing, and told her they had powerful healing properties. From then on she was hooked on beautiful rocks, and they went with her everywhere. After a proposal to work on an accessory line with the famed French bead embroiderer Lcsage fell through in 1986, she decided to design jewelry using crystals. “She wanted people to be beamed up without even knowing it,” says Ann Moss, who is married to Jerry Moss and also collects crystals. Michael Chow was not pleased: “She had the jewelry, I had nothing.”

The pursuit of a career was clearly imperiling her marriage, but Tina forged on. In 1986 she finally learned to drive. “I think when she started driving we got into trouble,” says Michael only semi-facetiously. He dates ‘86 as the year “Tina kind of went out in space with crystals and speaking of universal love. But what about your own children–you know what l mean? I wanted family, roots, all that boring stuff.” By that time Tina’s dear friend Antonio Lopez was dying of AlDS. The Chows took him in. Michael paid his medical bills and Tina nursed him, never knowing that by then she was already infected herself. She worked on AIDS benefits, helping Louisiana-born London socialite Marguerite Littman found the AIDS Crisis Trust in Britain.

By 1987, Michael admits, “there wasn’t much of a marriage.” Tina was flying around the world pursuing perfection in jewelry design. There was only one man, in Hong Kong who could polish the hole that held the cord to her pendants. She worked with a bamboo master in Japan. “Nobody else could make those tiny perfect knots,” says Bonny.

It was the year of living dangerously. She started an affair with Richard Gere, who excited her interest in Tibetan· Buddhism and brought her into contact with the Dalai Lama. (According to Gere, it was five or six years ago that he and Tina had a relationship. Tina tested positive for H.I.V. in 1989. He has been tested for H .I. V, a number of times since he was first aware of the disease, and has tested negative every time.) “She was longing to express her own talent – she’d never had something that was just her own little oeuvre,” says Bonny. “A spiritual search was beginning. The old was breaking up for the new. It was kind of like a bird molting.”

“I was sheltered for a long time,” Tina told a Texas newspaper while promoting her jewelry line a scant month before she collapsed in Tokyo. “I’m only now standing on my own two feet.”

The death of Andy Warhol in February 1987, followed by those of Antonio Lopez in March of that year and Jean Michel Basquiat in 1988, made Tina feel “that this circle around her, link by link, these people were evaporating,” says Bonny. “The times were definitely changing.” On May 16, 1988, ·Tina Chow gave a quote, which now truly sounds eerie, to a New York Times reporter for a story on drugs going out of style in the fashion world: “For years I subsisted on a diet of espresso and champagne. Now I don’t drink. I lost several friends to AIDS, and I felt my life slipping away while I continued to party. The fashion industry and the arts have been hit so hard by illness, many people are paying more attention to just sticking around.” Tina Chow did not know there was a silent time bomb ticking inside her.

The news that his wife had contracted AIDS scared and shocked Michael. “I was at risk for a period of time, of course I was.” He subsequently tested negative for H.I.V. and in January of this year he married fashion designer Eva Chun. He describes the experience of going through Tina’s illness and death “a little like the Cultural Revolution, a little like what my parents went through.”

Michael was present at Tina’s deathbed, but the two never came to terms. “That’s only for movie scripts. There was no forgiveness scene — it wasn’t articulated like that.” Could he look back on his relationship with Tina without rancor? Michael Chow had been staring out the glass doors in his Los Angeles living room toward the patio. He slowly turned his head around, took off his glasses, and looked straight at me.

“No,” he said. “No, I cannot.”

“I am going to be the best AIDS patient ever.” Tina announced to friends once she could bear to admit that she had the disease, in the fall of 1989. She began to research the virus and document her illness with the thoroughness and meticulousness that characterized everything she attempted in life. But even Tina Chow, surely one of the most privileged females with AlDS in the world, was frustrated by the utter disregard the government and the medical community have shown so far toward women with AIDS.

Women with full-blown AIDS survive for a shorter time than men, some experts believe, owing to the fact that they are frequently diagnosed later than men. It is not known whether AZT and DDI, the two drugs approved by the F.D.A. for people who are H.I.V. – positive, affect women differently than men. In the heterosexual transmission of AIDS, which is increasing at a rate four to five times that of any other risk category for the disease, AIDS cases among women outstrip those among men: according to the most extensive study published in the United States on partners of people infected with the virus, women are up to seventeen times move vulnerable to being infected than men. “The questions of why AIDS happens any faster or slower in women and what its manifestations are – these questions are only now being tackled,” says Dr. Farley Cleghorn, an AIDS researcher with the National Institutes of Health. (In the early years of the disease, 69 percent of those affected were gay men.) “Certainly the issue of women with AIDS came to light later, but what’s lacking now for women is the initial high-powered organizational push gay men had. Women were not admitted to any clinical trials for AIDS until 1990, and the National Institutes of Health did not even begin an office of women and health until 1990.” So far, it seems that the prominent women associated with fighting AIDS have not spoken up loudly enough for their own sex.

AIDS in women is complicated by the fact that it can often present itself initially with gynecological symptoms, such as yeast infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and cervical cancer. “If a woman has had severe or repeated yeast infections,” says Dr. Patricia Murray, who was one of Tina Chow’s doctors, “her physician should be sure to do a more detailed sexual history.” Yet so far the government’s Centers for Disease Control has not accepted such symptoms as criteria for an AIDS diagnosis. “Tina thought it was terribly unfair that women’s symptoms were not given more attention” says David Seidner. “For example, she was plagued by yeast infections, and she was resentful that there wasn’t more attention to women and the disease.” Despite her privileged status, Tina told her friends she often felt that as a woman with AlDS she had nowhere to turn. Says Seidner, “I remember her saying that she went to a meeting of an AIDS group in New York and she was the only woman. It made her feel uncomfortable. In certain instances she felt ostracized by groups who were supposed to be there for support.

Tina quickly decided not on1y that she was going to be a full participant in her treatment but also that she would eschew conventional Western medicine—rejecting AZT for a strict macrobiotic diet, holistic treatments, Tibetan medicines, and psychic healers. “Tina had a detailed, scientific approach to things, but there was a tendency to put a voodoo-hoodoo sense to it,” says Nadia Ghaleb. As the disease progressed, Tina was forced at crucial moments to accept the conventional treatment of American doctors, but she would submit only to those who were willing to consult with her macrobiotic counselors, one of whom became her “case manager.” At least a dozen doctors weren’t interested. “Tina was probably lucky,” says Bonny. “She had societal connections, she was well-to-do, and still it was hard for her to find doctors who respected her as a woman, as a person, as a participant in her care. She was supposed to follow blindly. Tina never followed; she asked too many questions.

Illness struck Tina when she was going through the final stages of what had become a very bitter divorce. Those fights continued while her relationship with Richard Roth fell apart. (Roth is now writing a screenplay about Tina Chow.) She kept the diagnosis hidden from the world at large, and for a long time she was unavailable to many who tried to contact her.

Tina told her children that she had AIDS over the Thanksgiving weekend in 1989. Even then it was supposed to remain a secret. The next day eleven-year-old son, Maxie called home crying, in a total panic. The teacher had asked the class what they wanted most for Christmas. Maxie’s hand had shot up instantly: “I wish there could be a cure for AIDS so my mother could be cured.” He was afraid he had done something terrible. “My darling,” Tina answered, “this is the most wonderful thing to have asked for. Never feel bad about that.”

“The greatest pain for Tina in all this was as a mother,” says Bonny. “Not being able to look after her children on a daily basis was so hard.” (The children now live with their father.)

Tina Chow was able to survive two and half years after the onset of critical symptoms, “a pretty long period of time that did beat the odds,” says one of her doctors, Brian Saltzman, co-director of the AIDS inpatient unit at New York’s Beth Israel Medical Center. While her restless search for treatment led her from a macrobiotic retreat in Pennsylvania to the beach in Hawaii, she also took the opportunity to re-evaluate her life spiritually, and she never stopped encouraging others. She even stayed in touch with Kim D’Estainville and offered him advice on their mutual illness. “I was going through a separation and divorce,” says Maggie Salamone, “and Tina counseled me about pain. She said the tendency was for the first year and a half to try to make a deal with God: If I do this, will you do that? She said she went through a long period of that.”

Tina Chow was a fighter. “Patients do better if they get more involved in their care,” says Dr. Saltzman. “Tina was one of the feistiest, most dedicated I’ve ever cared for, the most involved in her care, with the strongest will to live—and I’ve seen hundreds of AIDS patients.” Tina came to Dr. Saltzman last May in an extremely weakened condition—she was on a rigid macrobiotic diet and she had a serious yeast infection. He prescribed protein and vitamin supplements, which she took for a short time before returning to a still terribly strict but modified macrobiotic regimen. Her yeast infection which she described to Maggie Salamone as “an open sore all the way up to my belly button,” eventually disappeared. “I starved it out of my system.” she triumphantly told Mark Walsh. (“I would not say candida cleared through diet,” says Dr. Saltzman. “I’m not sure I can support that medical claim.”)

Richard Gere lent Tina his house in Westchester County for a few months last summer. From there she would have her driver load baskets of rocks, Tibetan furniture, pots and pans to prepare food, and her steamer into a red jeep to visit various close friends. “She gave very good hugs, long hugs at the end,” says Eric Boman. “She wanted to draw strength from you.”

One of Mark Walsh’s tasks was to pick up the messages on her answering machine in New York. Often there weren’t any. Although Tina’s family was selflessly and exceptionally dedicated to her, as were a few close friends, many of the rich and famous, the kissy-kissy socials and the moochers Tina Chow had once delighted with her beauty and sparkle, had all but disappeared. “She felt a lot of people had abandoned her—-and they did,” says Seidner.

Meanwhile, Tina was also tending to her material cleansing process. The woman who had lived most other life in appreciation of luxury, craftsmanship, and form blurted out one day, “It’s all stuff!”

By late summer she seemed to be failing. “In August she said she couldn’t stand the day-to-day struggle of it anymore,” says Seidner. “She was very depressed and she wanted to die.” Deep depression is common in terminally ill patients, and in her last months Tina Chow was no exception. According to Bill Spear, her case manager, the antidepressants prescribed had no effect. “She felt she had botched her life,” says Boman. “She felt it had all gone wrong, and she didn’t blame anyone except herself.”

But in October, Tina made an astounding rally. At the insistent urging of Michele Bohana—an activist for Tibet in . Washington and a friend who was unlike the visual aristocrats she was used to–she flew from Los Angeles to New York. The occasion was the appearance of the Dalai Lama for Kalachakra Initiation, a gathering of four thousand of the faithful to hear complex teachings and rituals. The Paramount theater at Madison Square Garden had been made to resemble a gigantic Buddhist temple, and for more than a week Tina sat through the grueling initiation and accompanying lessons. “There were seven straight days when His Holiness and other lamas spoke for ten hours,” says Bill Spear, who accompanied her.

“You’ve really done something wonderful for me,” Tina told Michele Bohana by the second day. “I brought her to His Holiness two to three days after she arrived,” says Bohana. “When she went in and when she went out, there were perceptibly two different Tinas,” The Dalai Lama personally gave her some Tibetan medicines and referred her to a very high lama, “a great mediator and practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism—very realized,” says Bohan. The lama’s counsel to Tina: “Put His Holiness in your hem. Heal yourself [and] all those others.”

“When he said that, it was like a light bulb went on—she realized what she was there for,” says Bohana. “If this woman had a regular life span, God knows what would have come out of Tina.” Back in Los Angeles, Tina tried to put the lama’s charge into practice. She decided Mae would endorse an AIDS hospice in Mexico which would be called Tina’s House, and she renewed her commitment to volunteering for Project Angel Food, a privately funded organization that prepares and delivers meals to people with life-threatening diseases, mostly AIDS. Tina Chow was back in a very different kind of kitchen. “She was fairly ill,” says executive chef Guy Blume, “but she had that really beautiful, soulful quality about her . . . ” She would come in once a week for three or four hours; she was very brave. One day she even fainted, but she was smiling when she came to—she was very calm about everything. And she was still beautiful. One day she decorated the tops of all the food boxes–three hundred of them.”

Early last December, Tina entered Saint John’s Hospital in Santa Monica. She had contracted toxoplasmosis, a parasitic infection that sometimes produces brain lesions and stroke like symptoms. She lost vision in one eye, was partially paralyzed, and could barely speak. “By then we were no longer dancing around the subject of ‘You’re dying,’” says Bohana. “I tracked down three monks. When the monks came, Tina was happy, She managed to whisper, ‘Oh, wow.’”

No one expected her to be able to leave the hospital, but she went home just before Christmas. “She was as clear as a bell.” says Bohana, who had flown to L.A. “Tina couldn’t speak, but she could look you in the eye. She spoke with her eyes. We talked about the end. I told her, ‘Everything is done, His Holiness is notified, all prayers are done.’ We locked eyes and recited prayers—she was totally and completely prepared.”

When the end finally came, eleven days later, Tina was fully conscious, without any drugs, and surrounded by love. Her bed had earlier been brought into the living room of her Spanish–style house overlooking the sea, where she had once delighted in watching whales float by. Now she stared at a picture of the Dalai Lama and fingered a mala, a Tibetan rosary. Her mother, her sister, her family were at her bedside. China was leaning over her mother and hugging her when she died. The moment was very peaceful.

Even in dying, Tina Chow couldn’t help looking elegant. Herb Ritts visited her in her last days, and recalls that she was perfectly turned out –“pressed men’s boxer shorts, little tank top, and silk robe thrown over her shoulders.” He held her hands. “Her hands were so beautiful that night.” Toward the end of her life, says Ritts, Tina was becoming a different woman. “She’d be a lot freer with herself, not so into the society stuff. She began to be more of a woman using her own creative energies.” And as she became more independent, he says, “Tina felt more a sense of herself. The memory of Tina that I will always have with me is seeing her one day in the sunshine out on her deck with no makeup on. She was kneeling down with her rocks and crystals all grouped around her, making her jewelry, smiling and very happy with it all. Her creativity was coming out.”