Original Publication: Los Angeles Times West Magazine, October 31, 1971.

Inside a phone booth at a gas station in Northern California an electronics student was shedding his no so mild-manner guise to become Captain Crunch, Super-Blue-Box Commander Man. Able to leap whole continents at a single bound and get his dime back.

A few minutes later, Crunch started shrieking to his partner: “Get in here, get in here, I’ve got the American Embassy in Moscow on the line.”

“This is the American Embassy in Moscow,” said the male voice with a faint Midwestern twang. The connection was beautifully clear.

“Are you the night guard?” Crunch’s partner asked

“Yes, sir.”

“What time is it there?”

“It’s seven minutes after 4 in the morning.”

What kind of small talk do people make to the night guard at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow?

“How’s the weather?”

“It’s about 65, it’s warming up.”

“Do you get American newspapers?”

“Yes sir, the come in on ticker tape.”

“And Russian papers?”

“They’re translated for us.”

“What did the Russians think of our last space shot?”

Klunk. Instantly the conversation was cut off.

“Don’t hang up, don’t hang up,” yelled Crunch, “I’ll lose my dime!”

“It was probably the Russians, “ he added nonchalantly. “They monitor incoming calls. They’ll did when they find out their phone system is as vulnerable as ours.”

Capitan Crunch is one of California’s heavy “phone freaks” – a group of 200 or 300 pranksters concentrated up and down the West Coast and scattered throughout the country – who, with the aid of “little blue boxes,” command illegally the world-wide telephone network for free.

In the mid ’60s, Bell, and almost every other phone company in the world, decided to convert billions of dollars of telephone equipment to a compatible system based on 12 tones. Ever since, groups of college students high on electronic circuitry, freckle-faced teenagers and blind kids with sensitive hearing have kept up with the latest telephone technology. They call themselves “phone freaks,” and they know American Telephone and Telegraph the way Ralph Nader knows General Motors, for they have discovered Ma Bell’s fatal mechanical flaw: All the “control signals” – telephone tones – which activate most of the equipment come over the same circuit we speak on. This means phone freaks can send control signals down the wire just like operators do.

Armed illegally with a little blue box, an ingenious electronic device which duplicates the 12 tones, with an expert knowledge of tandems, test boards and crossbar switching, and a repertoire of other secret telephone techniques passed on by friendly phone company personnel, phone freaks win radio contests by calling in first, listen to Dodger games from anywhere in the world, and even know how to call the President on his private line.

“I have Nixon’s number in Key Biscayne,” one freak revealed, “and the number of one of his private lines in the White House. It’s hooked up to the military phone system, Autovahn. I can call him whenever I want, but that would just be inviting trouble. It would be easier to tap into whoever he’s calling if that’s what you’re into.”

Five young phone freaks from peninsula suburbs near San Jose, including one blind boy, had come to study Captain Crunch as he performed on the world’s largest technological playground. They explained why they preferred phone freaking to hobbies like ham radios or hot rods.

“The phone company’s a monopoly, isn’t it?”

“Phones fascinate me, and I like bugging technology.”

“I just dig having a hobby.”

These teenagers admit to Cs and Ds in algebra and calculus but spend hours every day figuring out the phone network.

They all arrived carrying customized MFers – multi-frequency tone signals – the phone freak term for a blue box. The homemade MFers varied in size and design. One was a sophisticated pocket transistor built by a PhD in engineering, another the size of a cigar box with an acoustical coupler attaching to the phone receiver. The boxes, blue and black and gray, cost an afternoon’s work and anywhere from $15 to $30; they can be made from materials available at radio supply stores or ‘liberated’ from the local phone company.

So far, these phone freaks had devised 22 ways to make a free call without using credit cards. In case of a slipup, the phone freaks also know how to detect “supervision,” phone company jargon for a nearly inaudible tones which comes on the line before anyone answers to register calling charges. As soon as phone freaks detect the dreaded “supervision,” they hang up fast.

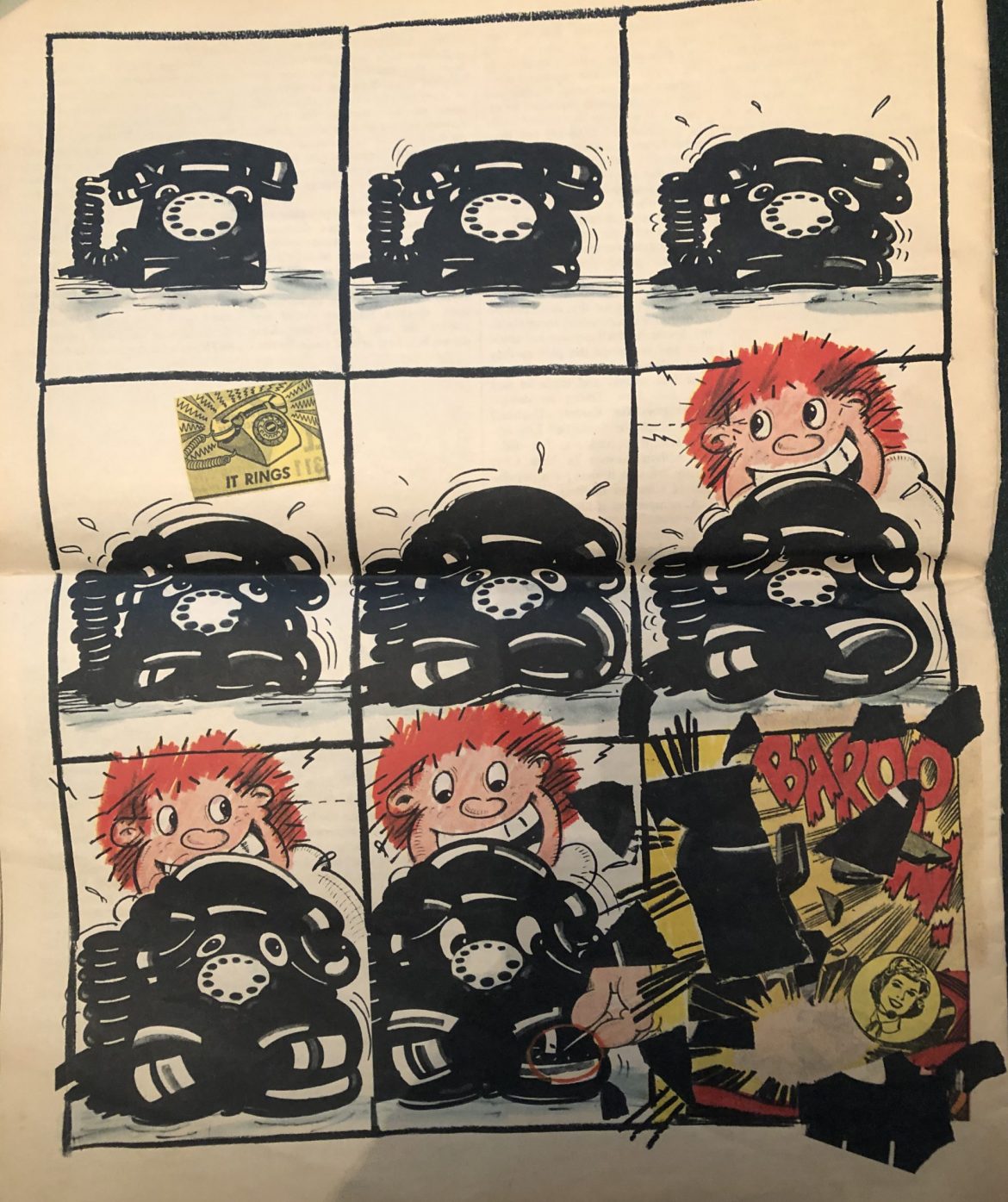

Captain Crunch was still in the phone booth pulling the red switches on his fancy computerized box. He got his name from the whistle found in the Cap’n Crunch breakfast cereal box. Crunch discovered that the whistle has a frequency of 2600 cycles per second, the exact frequency the telephone company uses to indicate that a line is idle, and of course, the first frequency phone freaks learn how to whistle to get “disconnect,” which allows them to pass from one circuit to another.

Crunch, intent, hunched over his box to read a list of country code numbers. He impersonated a phone man, gave precise technical information to the overseas operator, and called Italy. In less than a minute he reached a professor of classical Greek writings at the University of Florence. It was the middle of the night there, and the professor was motto affabile as Crunch’s partner talked to him.

“Always call me at this hour, Signor, it is a good time to find me at home.”

“Don’t hang up!” Crunch screamed again to his partner. So far he was still on the same dime.

“How about calling the National Observatory in Athens?” someone suggested. “They have a neat telescope.”

“All right,” Crunch said. “Let’s see, I use ‘Gateway City’ 183, the country code is 052 plus one plus the number.

“Don’t come on the line, operator. I’m transmitting data.”

Evidently the stars weren’t falling over the Aegean that night because nobody answered.

“Here,” said Crunch to the disappointed star gazer, and handed him the receiver to listen to Dial-A-Bedtime Story in London, where an impeccable Oxford accent was reading all about some creatures called Harem Scarem and Little Yo-Yo.

“The British are great,” the blind boy whispered. “You can Dial-A-Disc, Dial-A-Dish, or find out What’s On In London This Week.”

Crunch pocketed his dime.

With his eyes still blazing from his transatlantic triumphs, he explained his favorite method for calling free:

“First I call a number with an 800 area code; you know, the kind hotels have so you can call free for reservations. Personally I prefer the Army Recruiting 800 number. I dial direct and just before it rings Army Recruiting, when I hear I’m into the long-distance equipment, I either whistle off 2600 cycles or release “Start” on my MFer. The 2600 disconnects me from Army Recruiting but still leaves me in the long-distance circuit. Then I press another switch on the box ‘Key Pulse,’ and pulse out the number.

“I can dial anywhere.”

After school that day the phone freaks met at the blind boy’s house near San Jose to trade tales of their adventures and swap technical information. Being blind may mean lonely hours inside all day with nothing to do; being a phone freak means fun and friends who appreciate your acute powers of hearing, perfect pitch and encyclopedic knowledge of how the entire phone system works.

“The farthest out thing I ever did,” began the blind boy, “was call myself around the world. I had two phones right next to each other. First I called Hertz Rent-A-Car, whistled off, then MFed to London, Paris, Athens, Tokyo, Sydney and home. You get an echo on the line and about a three second delay. I pressed both receivers to my ears and said ‘hello, hello.’ Then I started screaming into the phone and doing all this weird stuff; it was blowing my mind. The operator in Sydney must have been listening because she broke in, ‘Sock it to me, Baby! Sock it to me!’ ”

He suddenly stopped.

“Hey, cool it gang, cool it. I hear my mom coming.”

Josef Engressia Jr., 22, the world’s number one phone freak, is also a blind phone genius with “perfect pitch.” He took his first phone apart at age three, and a few years later correctly identified the frequencies of the tones going through the long distance trunks which he could duplicate perfectly by whistling.

Joe’s family never could understand their son’s passion for phones and didn’t have one in the house for five years.

Joe, who can remember 30-digit numbers and 4,000 to 5,000 telephone numbers, recalls “the most painful period of my life. I was between the ages of 12 and 16. The only time I could use the phone was when Mother took me with her to the Laundromat once every three weeks, and I got to use their pay phone. That whole period retarded my phone development, but I’m convinced it made my motivation stronger.

“I went without lunch three times a week for two years to save $100 for a phone. I hid the money between the pages of my Braille Bible, and then called the phone company pretending I was my father saying his poor little blind son and daughter needed a phone in the house. That way they didn’t charge me the $25 deposit.”

Before blue boxes, Joe and the early phone freaks recorded combinations of multifrequency tones on tape which they then plugged into the telephone. They got the tones from an electronic organ after discovering that certain organ keys when played together exactly duplicated the 12 multifrequency tones. Phone tone number one was 700 and 900 cycles pressed together – A and F played in the fifth octave on the organ. The kids recorded the tones at half speed, edited them onto tape, then sent the tones out over the long-distance wires and doubled the speed. Sometimes they just plugged the organ wires into the phone and played their way around the world. A few budding rock stars experimented with their amplified instruments, and one 15-year-old from Santa Monica used his guitar to call “time” in Tokyo.

To make a free call anywhere in the U.S., all Joe had to do was whistle. In 1968, while a student at South Florida College in Tampa, Joe was caught for charging a dollar to whistle free phone calls anywhere in the country for his classmates. The local press dubbed him “The Whistler,” the Tampa phone company gave him a stern warning; South Florida College placed him on disciplinary probation and told Joe to knock it off.

Early last June, Joe, who had left college, was arrested in Memphis for possession and use of a blue box, but found guilty only of malicious mischief, fined $10 and given a 60-day suspended sentence by a sympathetic judge. South Central Bell, alerted to The Whistler in their territory, became suspicious when Joe phoned, left his number, reported he’d had trouble making a long-distance call, and explained precisely how to correct it. Joe’s bill, of course, didn’t show any long-distance charges.

At the time of his arrest, unemployed and living on a $97 a month welfare check for the disabled, Joe was unable to get a job with Central Bell where he had applied for work. However, subsequent publicity about his arrest brought Joe several well-paying offers from big business not related to phones, and his first job. He is now a troubleshooter on the lines at the nearby Millington, Tennessee, phone company, his lifelong dream of being a “real telephone man.”

“I would never think of MFing again, not even from a strange motel,” Jose said will all the fervor of a recent convert. “I make enough money now to put calls on my own telephone bill.” He paused, whistled 2600 cycles three quick times – not enough to disconnect the call but enough for the operator to come on the line. “Make sure the other party gets time and charges on this operator.”

Then Joe nonchalantly revealed a previously untold story about his arrest – he had planned it all along, he confessed, gambling that the phone company would play right into his hands.

“I was desperate for a job to get off welfare, so I really went out on a limb to get arrested. I knew I might have to spend three months in jail, but I figured the publicity would land me some sort of job, hopefully with the phone company.

“I knew the phone company was monitoring my calls because I could hear them doing it. You see,” Joe said with barely controlled glee, “I had a special high-powered amplifier and some other equipment rigged up to my line so that every time I clicked off from an illegal call I could listen to what the security agents were saying about me. It took them about six weeks to gather the evidence. They wanted to build up a good case.

It was lonely in that room all by myself, and every time I got turned down from a job I’d go and MF about 20 illegal calls. ‘Anyone for Moscow?’ I’d yell into the amplifier. “We’re gonna start rushing’ around here in a minute.’ And I could hear them exclaiming, ‘Did you hear what he just said?’ ”

But Joe bears no malice toward the security men who tried to catch him. I really have a soft spot in my heart for all three agents who tried to nail me. I credit them all with helping me to further my goals. The guy in Tampa was actually trying to get me job with Bell, but the higher ups wouldn’t go for it. Then when I left school and went home to Miami, the agent there used to visit me all the time. He’d always bring an engineer along to explain my answers, but in two and a half years he could never catch me. He got really furious once when I made 1,200 free calls in one week, and my bill didn’t show anything illegal. If he hadn’t pursued me so relentlessly and banned me from all three Miami phone offices, I might never have had the courage to take buses to faraway phone companies or stay in motels by myself. Those tours gave me self-confidence and helped me cut the apron strings from my parents.”

Babe Howard, president of the small independent phone company in Millington, describes Joe as “brilliant.” “With a brain like his, he should be in a phone research lab where he can capitalize on his hearing, but some companies don’t hire the blind. Of course if I spent billions of dollars setting up a foolproof system, I probably wouldn’t want some school kid telling me how easy it was to break. But I believe I’d want him on my side.”

Young electronics wizards at the nation’s top technical universities got their first inkling of phone freaking from reports of Joe’s arrest in 1968. Professors and students at major institutions pounced on telephone technical journals in their libraries. Especially coveted was the International Telecommunications Union’s Blue Book, published in 1966 which gives complete details on how the worldwide telephone system works. At one famous eastern university the book was in shreds in three days.

Phone freaks also ran technology seminars, courtesy of Ma Bell, often meeting 10 or 12 hours on huge nationwide conference calls (including Alaska and Hawaii). Sometimes a group of people would simultaneously call the same number, the busy signal would diminish and everyone talked on one big party line. A couple in San Jose who met on a busy signal were married recently, and some phone freaks serenaded them with the “Wedding March” on their blue boxes.

Some of the cleverest phone freaks work for the phone company and constantly contribute to the common data bank by feeding in secret information. Phone freaks know how to tap phones, although they rarely do so. Their code of honor forbids listening to other people’s conversations, although they have no qualms about monitoring one another or trying to find out what their girlfriends are saying about them.

But the “heavy number” in phone freak circles isn’t tapping into lines or even calling the President. It means stacking tandems, an elaborate and spooky technical process that can tie up millions of dollars worth of long-distance circuits by interlocking or “stacking up” long-distance trunks to each other.

A tandem is a piece of equipment which ties two long-distance trunks together. Here’s how it works: A phone freak in Los Angeles will call New York on a special three-digit code number, using the blue box which gets him into the New York area code. That way he can lock the circuit and the tandem in New York which in turn will connect him to another long-distance circuit connecting, for example, to San Francisco. To call Chicago or any other city, he repeats the process. Thus, the phone freak in Los Angeles has called Chicago via New York and San Francisco, locking the circuits or stacking the tandems along the way. He can criss-cross the country, stacking as many as 30 tandems, although the average is seven or eight. Eventually he can tie up all the long-distance circuits from a medium-sized city and “busy out” the city so that no one can call in or out.

“Oh, sure,” said a phone freak casually. “I could kill a city. With a lot of precalculation, I could kill a city the size of Bakersfield in 45 minutes.”

The ultimate phone freak trip is listening to the chirping noises of stacked tandems collapsing after a few phone freaks has hung up, then counting how many he’s stacked to make the call.

Phone freaks could get away with their games because the telephone system then so deftly manipulate was designed in the early ’40s, and is now technologically out of date. The newest phone system, ESS (Electronic Switching Systems), has a separate band for sending control signals down the line, making it impossible for anyone outside the phone office to control the switching network. ESS, which costs billions of dollars, won’t be fully in use until the year 2000. Meanwhile, the phone freaks are hard at work figuring ways to break it.

“If you steal from the phone company, their first response is not to get you but to redesign their equipment so you can’t do it again,” said one highly trained freak. “They use security people just to harass you and chase down winos who break into pay phones.”

He also explained why he felt no qualms calling all over the world free. “The more sophisticated machines become, the easier they are to mess up. They get farther and farther away from human control. To a machine something is either right, or it isn’t. they can’t tell if something is weird. We couldn’t do a thing if we had to go through a manual cord board operator.

“The kids are smart, but they’re not smarter than the phone company. AT&T knows the freaks are there, they know how to correct the system. But it’s more than a question of economics. It’s admitting they’ve made an engineering error and are willing to fix it.”

Until recently, phone security agents took a lenient view toward youthful offenders, probably figuring Ma Bell had enough image problems without sending little blind boys to jail, but now the Bell System has declared all-out war on phone freaks.

AT&T spokesman Dennis Mollura explained that in the first eight months of this year there were 37 arrests and 17 convictions for blue box fraud. None arrested were gamblers or dope dealers; most were college students who placed calls through long-distance information numbers, including five students who were arrested at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo for calling Russia.

AT&T uses three methods to look for blue box frauds. They spot-check lines or investigate suspicious lines at individual plant service centers. They conduct “traffic pattern analyses” of suspect phone lines and use computers to scan for unusually large numbers of calls placed to 500 or 800 numbers from the same place.

All states have laws governing “fraud by wire.” California has one of the toughest, making it a felony to use or conspire to use, to purchase, manufacture or assist in the manufacture of “mechanical devices” to defraud the phone company. And any calls placed across state lines using a blue box are a criminal offense.

The phone company is getting tough about phone fraud with good reason. Overall phone fraud is up 700 percent since 1965, from $2.7 million to $21.6 million in 1970, mostly due to illegal use of credit cards and illegal billing to a third number. These figures do not include estimated losses from blue box fraud, probably because the phone company has not until recently considered it much of a problem. Mollura said blue box fraud costs the corporation “somewhere between $50,000 and $100,000 a year,” but that estimate seems unusually low.

At present commercial rates, five gamblers (or one very active phone freak) can use up to $50,000 worth of phone time just by calling Miami to Las Vegas less than two hours a day, five days a week.

Neal Hasbrook, president of the California Independent Telephone Association, tells a different story. He says it’s impossible to tell the revenue loss from blue box fraud because blue box callers leave no records.

“We’ve heard speeches all across the country about these boxes from phone company officials who aren’t worried so much about the kids using them as they are about gamblers and members of crime syndicates. There’s equipment in the works to catch them, but it’ll take some time to install.”

At a security seminar of independent telephone companies, held in Los Angeles last May, curious officials called Hawaii with a recently seized blue box. They estimated blue box fraud at “$50 million annually in unbillable tolls,” a far cry from the AT&T estimate of $50,000 to $100,000.

Do old phone freaks die? Never. Some lose interest in the crossbar switching game; they get married, go to work, even for the phone company. But others still pursue electronic fantasies.

One ex-freak on the West Coast is an executive at his local Bell Office. At his family’s country home he has set up a private telephone network featuring a number to dial to turn on the sprinklers in the organic vegetable garden. Next year he plans a light show on a nearby lake, all via direct dialing.

Even Captain Crunch plans for the future.

“I can’t wait for my city to change its traffic lights to radio control. I’m going to build a little transmitter so that every time I come to an intersection I can press a button and the light will turn green.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.