Village Voice – November 25, 1971

New York is dead, everyone complained. The last thing to hit town was “Jesus Christ Superstar,” and it was so unbelievably crass. The major art openings were over, and the holiday parties hadn’t yet begun. Dull dull dull. But didn’t Rex and Truman rave about some divine hippie drag queens from San Francisco who actually wear glitter on their “private parts” as well as their eyelids? Right. “The Rockettes like rocks, and the Cockettes like — ” How utterly outrageous!

And weren’t they opening down in the slummy crummy East Village along with Sylvester, a black rock queen who sings falsetto? How off off can you get? And isn’t this the Year of the Gay? — it’s all right for men to dig other men in public. Everyone understands now. And hasn’t the underground press been covering the Cockettes favorably for over a year, even though the regular San Francisco press accepts their ads but doesn’t review them? Isn’t it time for something different? Let’s discover the Cockettes!

Not since Andy and Edie had New York made a group of society’s freaks its very own darlings in one short week — seven days to scale the highest media peaks, only to fall opening night with a great dull thud. How come? One reason is that the media-heavy audience came opening night expecting to see some sort of new art form and got comatized instead; but more importantly, the Cockettes were victims of the Big Hype — that peculiar New York phenomenon whereby people and things are declared hot, cool, in, out, under, and over. The poor little gold differs of ’71 from San Francisco made a big mistake — they believed it.

Reality is fantasy and fantasy is reality to the Cockettes. Their life style is carefully contrived to blur if not actually diminish the distinction between the two. So when the Big Apple gave them the Hype they were ready for it. “Darling, we’re the toasts of the town, they love us to death!” said Big Daryl, a Cockette leader. Never mind the hassles with the producers, the el cheapo production, the lack of a sound system to rehearse with, the cockroaches and the broken plumbing in the hotel, or even the parties the nights before that made rehearsing almost impossible, because the Tinsel Tarted Broadway babies were having their pert little behinds kissed bought up and downtown and Ziegfield wasn’t around to ask if they could sing or dance. Nobody did. “I’m Goldie Glitters, and I go to all these ritzy penthouses every night, and these photographers keep wanting to take my picture.”

Performance for the Cockettes is mostly an excuse to live a freaky life style. Why be a hairdresser or work in a third-hand store if you can be a Cockette and spend all day getting dressed up like your favorite movie star? The drag’s the thing — the Tinsel Tarts spend a lot more time on themselves than they do on the shows. In San Francisco the Cockettes are pure hippie-nostalgia street theatre with rinky tink piano, clever lyrics, and tons of glitter thrown in for good measure — gay hippies plus women who love to show off for their friends. There are far too many freaks in San Francisco for them to be considered avant garde, political, or revolutionary. It’s a $2.50 midnight show at a funky old Chinese movie house where you can watch Betty Boop festivals and dig the spectacle. Stoned at 2 in the morning, you don’t care if it moves. The indulgent audience is half the show, and knows it.

But the Big Apple declared the Cockettes media myths, the “fashion and faggot aristocracy” came out en masse to view their drag for inspiration, the ticket price shot up to $6.50, and Time, Life, Women’s Wear Daily, etc., all showed up to review them. The opening night’s theme song should have been “Please baby,” pant pant, “give us some new freaks to love.”

It’s easy to love the Cockettes. Their zany behavior turns on even the most hostile people, and every personal appearance is a major production. Integral to the making of the myth were the word-of-mouth reports spread around town by key writers, editors, or celebrities who saw the Cockettes behave outrageously at the Whitney, in Max’s, and at all the posh parties where they were honored guests. Everyone expected they’d be better on stage, but that’s a misconception. The Cockettes are much better in real life. I traveled with them for 10 days, and it was pure insanity all the way.

At the San Francisco airport pandemonium reigned from the moment the Cockettes stepped off their chartered bus, along with three tons of luggage that was heavy on the cardboard and tinsel. “Remember, girls,” Pristine Condition yelled, “The password for New York is Sugar Daddy.”

“Did you see that?” Mr. whispered to Mrs. Iowa at the baggage check as Link floated by in a one-piece latex bathing suit with a beauty queen banner of girl scout badges pinned to the front. And when Wally – in six-foot plumes and a pair of plastic Halloween pumpkins filled with gold tinsel suspended over his breasts – began beating his tambourine and asking for “tricks or treats,” four people canceled their flight.

Bystanders were treated to a wacked-out visual feast. In addition to 35 Cockettes, Sylvester’s musicians came with their old ladies, groupies appeared bearing gifts (Grasshopper, a favorite Cockette groupie, even flew to New York), several dozen awestruck airline employees gathered to gape, and one uptight tv cameraman was furious. “This is worse than a double X movie.” Nobody’s mother came to wave goodbye.

The “Cockette party” of 45 had to sit in the back of the huge 747, along with a few straight passengers who got mixed in. They either opted for stereo headphones and tuned out for the duration of the flight or slumped way down in their seats behind books on California redwoods.

The stewardesses couldn’t handle the commotion. One dropped her oxygen mask when the Cockettes applauded her act, and her partner, a blank-looking blond in a pinafore, just stood watching quizzically as one of the Cockettes called out, “Hey, we made a movie about a girl whose drag looks just like yours – ‘Tricia’s Wedding.’”

The Tinsel Tarts spent the rest of the flight “ritzing” around the economy lounge of the 747 where they allowed curious passengers and shy closet queens to buy them beers. One little old lady in an orlon sweater set and mink hat squinted at Wally. “Are you girls in high school or college?” “Neither. We’re Miss America contestants.” A belligerent drunk confronted Lendon, resplendent as Carmen Miranda: “Are you a man or a woman?” “We’re both, honey, and that’s just for starters!” By the end of the long flight everyone was getting very cozy. The Cockettes were singing show tunes for fellow passengers, who joined them, happily posing for one another’s Instamatics and Nikons just as if the Cockettes were some stray Indians they had found in the Grand Canyon. Smile click. Smile click. “My wife won’t believe this. Heh heh. Thanks a lot.”

The flight marked the culmination of more than three months of broken promises and tight money while trying to plan the New York tour. The New York people had originally come to them. The Cockettes were not actively seeking an eastern tour. Two New York producers had strung the Cockettes along from July to October, promising a Halloween opening at the Fillmore East. The Cockettes – most of whom are on welfare – stopped doing new San Francisco shows, and when the rent fell due at their three communes, they couldn’t pay it. One of Bill Graham’s yes men, after taking a month to make the decision on the Fillmore, decreed “The Cockettes will diminish the Fillmore East’s reputation as a rock palace,” which ought to be news to the neighborhood junkies.

Finally a San Francisco rock lawyer got them the Anderson Theatre, a block down from the Fillmore. Harry Zerler, a young, former talent scout at Columbia Records who had never produced a theatrical show before, but whose father, Paul Zerler, had been around the business for years, flew out to California and saw the same wild and funny Cockette show that Truman Capote loved and that sent Rex Reed to wondering enthusiastically, “Will the Cockettes replace rock concerts in the ‘70s?” The Cockettes were thrilled. Long snubbed by the local aboveground press, they had at last been discovered by the bigtime New York media. Zerler promised to bring the Cockettes to New York, and the myth began.

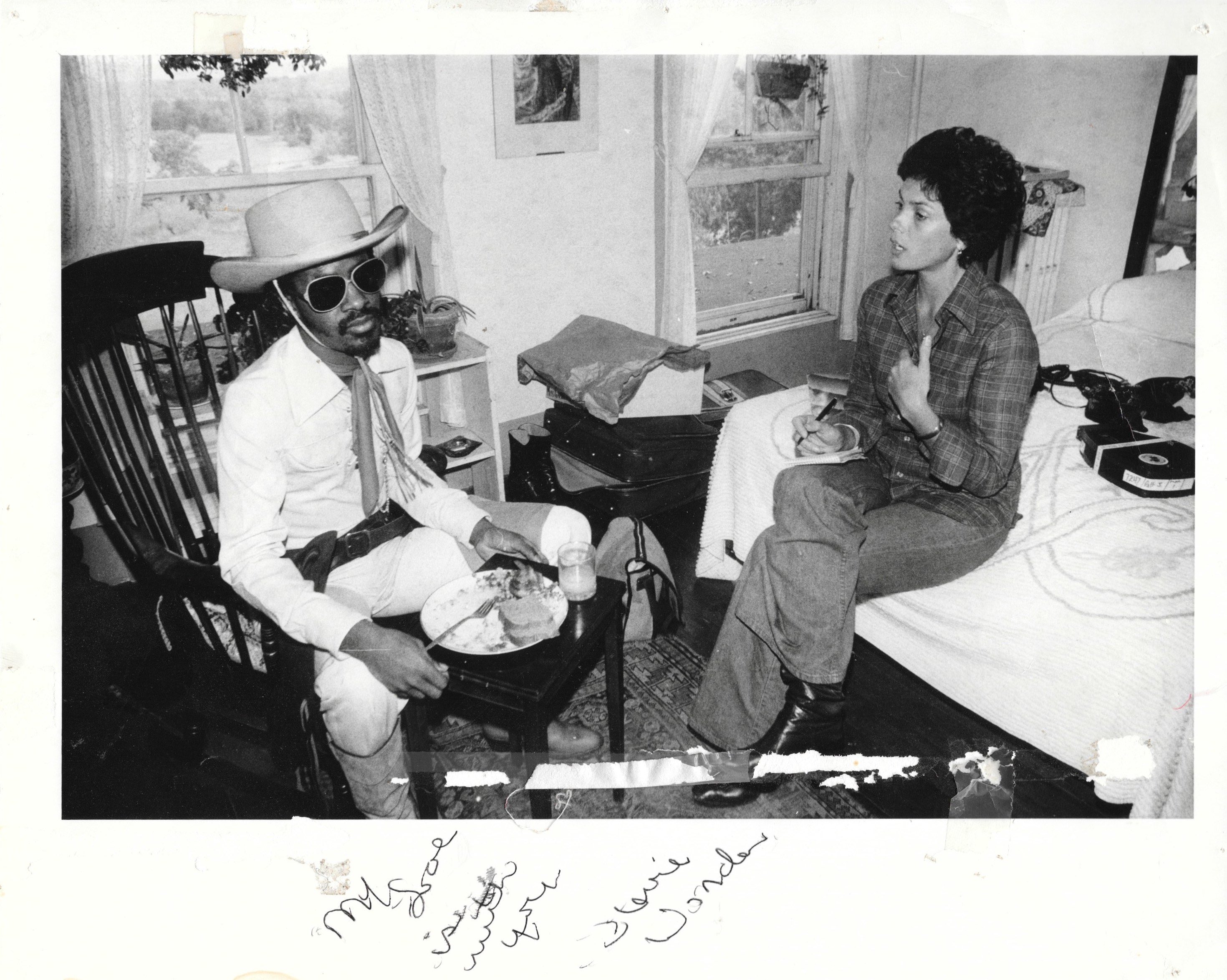

Even though the Daily News wouldn’t print Reed’s raving review, the Washington Post and many other papers throughout the country did. I wrote a favorable piece on the Cockettes for The Voice, and Rolling Stone published an article a short time later. Those three articles became the basis for all the hype in the Cockettes’ ads: “This is the most outrageous thing I’ve ever seen” – Truman Capote. “Insanity becomes reality, fantasy becomes truth,’ etc. – Village Voice. Both quotes were taken out of context, but that sort of hyperbole is justified by the producers in terms of the amount of money it takes to transport 45 people across the country and put them up for three weeks, especially people who sign the hotel register “Miss Creemah Ritz,” “Eatapuss Rex,” and Scrumbly. Paul Zerler figures it cost him $40,000. The Cockettes didn’t think setting the ticket price at $6.50 was fair, but they didn’t fight it – after dividing the money 40 ways they were only making $75 a week each plus lodging. The Cockettes have also yet to see a penny of the profits from their film, “Tricia’s Wedding,” but they are usually too engrossed in fantasy to seriously worry about finances.

Until the moment they landed, the Cockettes had no idea where they were going to stay. Rumor had it they were going to be put up in a one-bath, three-bedroom house in Connecticut with 25 cots set up in the basement. They got the Hotel Albert instead, in the Village, where on a good day the hallways smell somewhere between old socks and vomit. Miss Bobbie, 17, the youngest of the Cockettes and so beautiful he was offered a modeling audition at Harper’s Bazaar, cried upon seeing the Albert. She expected maybe the Plaza. The rest of the troupe amused themselves with cockroach counting contests in their suites. There was no room service. Pretty tacky for swishy West Coast queenies, but not so different from the Haight either.

It was very difficult to reach any of the Cockettes by phone at the Albert since several had changed their names when registering. Big Daryl vacillated between Harold Thunderpussy and Miss Creemah Ritz and confided his fears of being typecast forever as the whorehouse madam, especially after two janitors mistook him for Mae West on Halloween night.

If the hotel wasn’t “fabulous enough,” the Cockettes’ arrival at Kennedy had more than made up for it in advance. Danny Fields, the skilled rock PR man, had everything arranged. About 100 freaks were on hand, including two third-stringers from the Factory, and Superstar Viva’s husband, Michel, shooting videotape. Few of these people had actually seen the Cockettes perform, but that didn’t seem to matter. The rest of the New York airport crowd watched silently bemused with a so-what-else-is-new expression that contrasted sharply with the jovial hilarity at the San Francisco airport. I sensed New York would be a lot more difficult for the Tinsel Tarts and wondered if the Cockettes felt it too, but they were surrounded by local admirers, including suave Errol Wetson in total black velvet, the “fabulous millionaire hamburger king” as Dennis Lopez, Sylvester’s manager, referred to him. Suave Errol had wined and dined Dennis one night along with Warren Beatty and Roman Polanski. Dennis, used to paying for his own meals with fellow record company flacks, was properly impressed. (Actually Wetson is part owner of Le Drugstore and heir to a chain of 153 hamburger joints.) Suave Errol was dying to introduce the Cockettes to New York – there’s more to life than burgers – and thereby launch himself as the arbiter of a new social phenomenon in the process. “I heard about the Cockettes from my friend Truman, and New York’s been so quiet, so dead, something’s gotta happen. No, I haven’t seen the Cockettes perform. I don’t have to. I can feel their vibrations.”

Later that night Wetson hosted the Cockettes’ first New York party at this empty East 62ndStreet townhouse. Diana Vreeland, grande dame of Vogue, designer Oscar de la Renta, and executives of the hamburger corporation came along to catch the action. The Cockettes gave it to them – in wild costumes they uninhibitedly danced, sang, romped, and stomped. Wetson’s comptroller, perhaps sensing his young boss’s enthusiasm could have some future financial implications, commented, “They’re great at a party, but can they act?” Diana Vreeland was much more positive. She was truly impressed with the originality of the Cockettes’ drag and felt they had put on the best fashion show she had seen in a long time. “What’s so marvelous is that they look happy, truly happy, and that’s so rare these days, don’t you think?”

Meanwhile the Cockettes were digging the plush surrounding, their usual milieu being a couple of joints or a bottle of Cold Duck in the Haight. “Wow, we’ve never been treated like this before, with champagne and all,” said Lendon. After Suave Errol’s bash the group made a pilgrimage to Max’s Kansas City and turned the place upside down. In two days they completely revitalized the sagging dragging atmosphere at Max’s, and according to the regulars, “brought the place alive again.” After the third straight night there the Cockettes were allowed to charge hamburgers and Harvey Wallbangers, which was fortunate since they hadn’t been paid and were actually going hungry – but they were getting lots of attention, hype hype. The first night at Max’s, Pristine Condition fell out of her chair when she saw “Trash” star Joe d’Allesandro. She swiped his bread roll, brought it back to the Albert, shellacked it, and sewed it on a hat. That night rock critic Lillian Roxan told Prissie, “I always wondered what it was like to take New York by storm, now I know.” That was the sort of comment that got passed around town by word of mouth to turn on the general populace.

During the week before opening I must have gone to 27 parties with the Cockettes, on the East Side, on the West Side, in the Village, in penthouses, lofts, museums, and basements, gotten a total of 15 hours sleep, met two thirds of the freaks of New York, and began to suspect that all of Manhattan was gay. New York was bored and the Cockettes were so joyous they were almost wholesome. The Tinsel Tarts became the hottest numbers in town. They got a standing ovation at the Brasserie on Halloween night, then a ride home to the Albert in Marlene Dietrich’s silver limousines, which stretched the fantasy beyond all imagination. “The chauffeur, who evidently just cruises around picking up freaks, told us she’s out of the country and doesn’t own a television set. Honey, it was outrageous, and lucky, because we didn’t have the money to pay for a cab.”

The fantasy hardly ever stopped. Robert Rauschenberg flipped for Pristine Condition, John Rothermel, and Goldie Glitters at a Whitney opening and gave them $1000 when he found out they were hungry and broke. “The only people who support artists are other artists.” “Honey, that was Bingo with a B,” Prissie said. Taxi drivers usually turned off their meters and often gave the Cockettes drinks and joints. After Goldie Glitters offered to put one particularly polite cab driver on the guest list for opening night, he declined, saying he had a “very square wife.” “That’s okay,” said Lendon, dressed in a girl scout uniform with saddle shoes, “so do I.” Candy Darling acted like a perfect lady and invited them to her press conference. Holly Woodlawn taught them how to scarf dinner from fancy hor d’oeuvre trays. The Fontainebleau wanted the Cockettes for December!

Throughout this madness the Cockettes starred, wherever they went – at the erotic film festival party, the Screw anniversary party, Le Drugstore, where Suave Errol gave them another party and fed them, and in front of the clicking camera phalluses of scores of photographers who invited them to pose. David Rockefeller, shy about attending opening night, sent his chauffeur down to the Anderson to buy 11 tickets for the second night’s performance. Rex Reed, given 30 free tickets by Paul Zerler, was organizing a busload of celebrities to attend opening night and Suave Errol was throwing the after-the-opening party at guess where?

Days began at 2 p.m. and ended at dawn. The Cockettes were living just like the girls in the ‘30s musicals they parodied. Stage door Johnnies that would have freaked Busby Berkeley were saying goodnight early in the morning. One evening at Max’s, after underground star Taylor Mead’s boyfriend stood on a table, sang to Taylor, and simultaneously stripped for the benefit of the Cockettes, I asked John Rothermel, “Madge the Magnificent” in “Tinsel Tarts,” and Big Daryl, in Eleanor Roosevelt drag for the evening, what they thought of New York. “I know we’re degenerate,” said John, flipping her boa, “but we weren’t prepared for the nihilism of New York.”

Early on in the week the New York establishment press began to get very interested. The Post ran a story saying the Cockettes were to drag shows as Niagara is to wet. Life’s entertainment department was dying to cover them, “but we’ll never get it past our managing editor.” They sent a photographer opening night anyway. Esquire decided to go ahead with a story, after having been told about the Cockettes over a year before. A Harper’s Bazaar editor was ecstatic. “That sounds just like the sort of thing we want to get involved with.” Time and Newsweek were coming to the opening, as was the Sunday Times. Women’s Wear was really in a tither. They wanted to run something but felt uncomfortable using the word Cockette in print, especially since they had recently run an interview with rock star Sly Stone and quoted him as saying he was “happy as a motherfucker,” and a big Chicago garment mogul had canceled his subscription. The Washington Post, already hipped to the Cockettes from Rex Reed’s review, sent the same reporter to cover opening night who had just returned from writing about some other queens at the Shah of Iran’s 2500thanniversary bash. Even the local tv news, usually much too conservative to cover drag shows was sending a crew to film at the Anderson. I was approached to revive a Cockettes film project I had begun and then dropped. We decided to go ahead, and got the Maysels Brothers to shoot opening night.

The producers were spending an inordinate amount of time hyping instead of insisting the Cockettes rehearse, but Harry Zerler still wasn’t satisfied that the Cockettes had done enough to promote the show(!). “I haven’t seen any handbills passed out on the streets of New York,” he yelled at Sebastian, the Cockettes’ mild-mannered manager, and why are they so filthy? All the front rows are littered with bottles of Ripple. Next time I’m going to produce a bunch of compulsive anal retentive people.”

Danny Fields said the Cockettes were the easiest act he had ever promoted. “I haven’t seen such enthusiasm from the press since the Rolling Stones’ tour of the U.S. in 1969.” Opening night was over-sold and everybody was clamoring for tickets. “No,” barked one of the theatre staff. “I don’t care if John and Yoko come to opening night. There’s no excuse for mediocrity.”

Every once in a while reality would rear its ugly head. Dusty Dawn felt terrible. It was bad enough that New York laws prevented her from dancing on the stage with her son, 16-month-old Ocean Michael Moon, “the world’s youngest drag queen,” on her back, but Ocean had developed a terrible rash. Eight-and-a half-month-pregnant Sweet Pam’s baby dropped. And Wally, still wearing the plastic Halloween pumpkins, had had an emergency appendectomy five days before leaving San Francisco and was afraid he had glitter in his incision.

The producers didn’t have time for such mundane details. They were trying to cope with an inadequate budget – the Cockettes had kicked out 24 footlights and the soundmen were scrounging around for $25 mikes – but the Big Hype continued, so I took Wally and Dusty to the emergency room of Columbus Hospital for a check-up. Nonplussed would hardly be the word to describe the good sisters upon Wally’s arrival, but they remembered charity begins at home – they let him keep his 47 bracelets on. He had to leave his gold tinsel outside with me, however. The doctor told Dusty she obviously didn’t bathe her baby. She was indignant. “I bathe Ocean twice a day – it’s just in New York when he rolls around on the sidewalk he gets a lot dirtier.

By the end of the week the Cockettes had barely rehearsed. The sound system hadn’t been installed and the Tinsel Tarts insisted they needed a different set. Harry Zerler balked, so the Cockettes stayed up all night Friday anyway, building a new, special-for-New-York cardboard set. On Saturday they could barely keep their eyes open. At dress rehearsal Saturday night the hastily put together sound system broke down completely. Such was the power of the Sunday Times, however, that three Times photographers interrupted dress rehearsal for over an hour to get “exclusive” pictures.

Meanwhile, Sylvester’s three back-up singers had left for Washington to sing the Black National Anthem at the White House. From the Cockettes to Nixon? I would have believed anything at this point – but the girls didn’t return and nobody knew where to find them. “They were last seen with the President.”

Dress rehearsal was really the first full rehearsal. The Cockettes didn’t know how to use mikes or project their voices and on the big Anderson stage they came across like a parody of a parody, only it wasn’t funny – it hurt. Obviously opening night would be a painful experience, but the Cockettes didn’t understand.

They consistently refused to deal with reality. Sebastian, worried about technical difficulties, pronounced the show “great.” Suave Errol didn’t think so. What a dilemma – hundreds of people invited to his big party and his social standing was on the line. Where was Truman now that he needed him? Out in California.

The Cockettes declined rehearsals Sunday and toddled off to one more press party, at John de Coney’s, a hip barber shop on Madison Avenue where scores of reporters and photographers were invited to watch the Cockettes get their hair done. Before leaving I asked Goldie if she didn’t think it would be better to spend the time rehearsing, but the PR girl from the barber shop had arrived, not about to be thwarted. “But they’re waiting for you and Jacqueline Susann will be there.” Miss Susann never showed, but the Cockettes sipped wine under the dryers, posed endlessly for the 20 photographers present, and answered reporters’ questions that were definitely a case of life imitating Grade B flicks.

The Crawdaddy man: “Is it true the Cockettes had an orgy via closed circuit tv?” Answer: “No.” “Well then, what do you expect to get out of tonight’s performance?” “Enlightenment.”

Then Goldie divinely ensconced under the dryer, started telling her dreams to the film interviewer. “I dreamed I was an olive in a martini glass, but no one would swallow me – oh hello dahling, come be in my movie.”

Opening night was everybody’s movie, from “Footlights Parade” to “Phantom of the Opera.” According to Rex it was the “Craziest, wildest in New York’s history.” The Big Hype had really worked. The Anderson was jammed. Hundreds of fashionables pushed and shoved their way through the one open door. Beautiful People and big-time celebrities had to plough through just like the hoi polloi. Literati, glitterati, and culturati rubbed shoulders with dreaded freaks and every important drag queen in town. Some groupies had sprayed their bodies completely silver, others carried teddy bears, one even brought a whip.

The WWD photographer was beside himself. How could he shoot Gore Vidal, Allen Ginsberg, Angela Lansbury, Alexis Smith, Robert Rauschenberg, Rex Reed, Peggy Cass, Diana Vreeland, Nan Kemper, Clive Barnes, Sylvia Miles, Kay Thomson, Bobby Short, Elaine, Bill Blass, Estevez, Tony Perkins, Dan Greenburg, Nora Ephron, Mrs. Sam Spiegel, Jerry Jorgensen, Ultra Violet, Candy Darling, Taylor Mead, Gerard Malanga, John Chamberlain, Cyrinda Fox, Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis, the entire cast of “Jesus Christ Superstar,” The President of Gay Lib, a dozen Vogue editors, two real princesses, and the night clerk at the Hotel Albert?

At 8:30 Sunday night, when the doors to the Anderson were supposed to be open, Sylvester was still on stage rehearsing. His backup singers had suddenly reappeared at 7:30 and now he was arguing with one Sweet Inspiration and one Supreme who he had hired to take their place. The Cockettes, dead tired and not yet dressed, were quietly munching turkey sandwiches in the front row while half the “ritzy penthouse” people of New York were shrieking and fighting to get in the door. Truman sent an encouraging telegram – “keep it gay light and campy” – and the delighted Cockettes dedicated the show to him.

The audience came to get wrecked and thrilled by a fantastic new set of freaks. But as soon as the curtain went up it was all downhill. The audience was dying to be surprised, outraged, anything. They loved Sylvester, even after 45 minutes, but the Cockettes were hopeless. The sound system was terrible, the show was too slow to crawl, and the Tinsel Tarts were even too tired to be themselves. They forgot lines and bumped into each other, all this for the media heavies and literati. “My god, how could they disappoint us like this?” After 40 minutes, when Taylor Mead shouted “Bring back Jackie Curtis,” people began to get up and leave. (Jackie should love the Cockettes. After being panned everywhere when “Vain Victory” opened, he’s suddenly hot stuff in all the comparative reviews.)

One man in the audience, who had slept through the entire show, awakened and promptly vomited all over Princess Delores Rispoli, one of Rex’s guests. The usher was indignant. “What are you, some kind of vomit freak?” It was a fitting climax.

The critics were unanimous. “Having no talent is not enough,” declared Gore Vidal. “Dreadful,” pronounced Women’s Wear. The Sunday Times headlined, “For This They Had to Come from Frisco?” Lillian Roxon wrote the only favorable review, for the Daily News. She said the Cockettes were 15 years ahead of their time.

The party later a Le Drugstore was the expected mob scene. Inside Wally was trying to explain to an unsmiling woman reporter from Time, “But you don’t understand, we’re not professionals, we’ve never been professionals.” And outside, late-arriving Cockettes were barred from entering because too many people were already inside. “But it’s our party, let us in,” pleaded Reggie.

By the next morning Suave Errol had dropped the Cockettes forever. Ironically the strong dose of failure reality opening night was like a shot of adrenaline for the Cockettes. By the second night they had improved considerably, and the audience loved them, but none of the hypersters were around to see it. The Cockettes blew it. They had embarrassed the media moguls and weren’t about to get a second chance.

Harper’s Bazaar no longer wanted to get involved. Dick Cavett made them sit up in the balcony, and David Frost’s producer, alienated by Sylvester’s’ “being nothing but a queen,” canceled them one hour before showtime. The Big Hype was already looking for something new to swallow whole – and then spit out.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.