Original Publication: Newsweek, January 22, 1973.

If you’re young and lovely, brilliant, sensitive, intense, independent—capable of hitchhiking all over the world alone, having sex with whomever you choose, driving a Manhattan taxi—shouldn’t you feel liberated? The answer is no. Ingrid Bengis tells you why not in her remarkable book, probably the best answer yet to any man who wonders, “Just what is it you women want?”

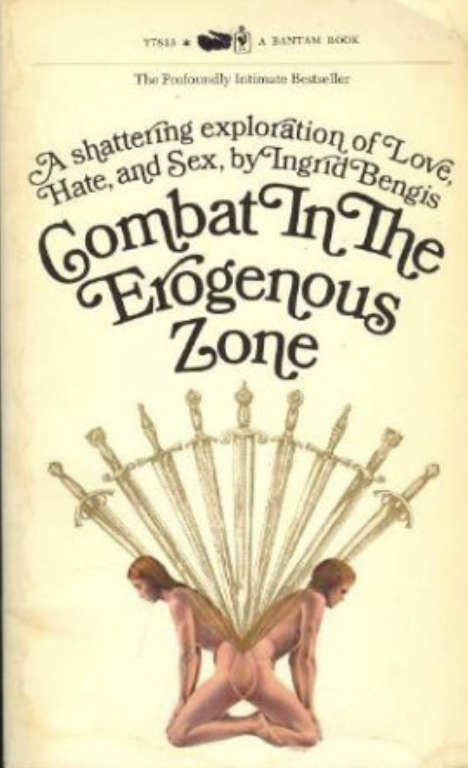

Despite its slick title, “Combat in the Erogenous Zone” is not another feminist polemic in which women are treated as so many oppressed statistics. The book, a series of very personal dialogues the 28-year-old Ms. Bengis carries on with herself, is intensely human, filled with pain and ambivalence—the same emotions many of us feel who cry out for “liberation” but then find difficulty in accepting the psychic isolation that liberation so frequently imposes.

With honesty as her chief weapon, Ingrid Bengis relentlessly probes her own life experiences, from the feelings of paralyzed fear at age 12 when anonymous hands feel her up on rush-hour subways, through a string of disappointing affairs with men who seem to substitute orgasms for intimacy. Finally, in her mid-20s, she ends up a reluctant man-hater. “I don’t think I ever chose man-hating to be part of my life,” she writes. “It is a defense against fear, against pain. It is a refusal to suppress the evidence of one’s experience.”

Body: Resentment towards men is not the core of the book, though Ms. Bengis displays a sharp awareness of the myriad ways they put down women—especially the type who specializes in “understanding” women. Rather, by exposing her own anguish and self-contradictions, she provides a devastating portrait of the human needs that prompted the women’s movement in the first place. She refuses to accept the idea of abortion easily or mechanically. She doesn’t know whether to be proud or terrified of the way men respond to her voluptuous body. She hesitantly gropes for the consequences of intimately loving another woman. As a self-defined “puritan romantic,” she can’t square her “forever after” fantasies with today’s super-cool relationships.

In the end she wants a deep and lasting traditional form of love. “I cannot be the completely feminine woman of the ‘50s,” she pleads, “the … sexually free woman of the ‘60s, and the militant, anti-sexist woman of the ‘70s. I cannot ignore the fact that my own life has unfolded slowly, that it has been a part of all those trends and none of them.” Ingrid Bengis’s book, the record of her struggle to “lead a decent life,” has probably moved both women and men on a deeper level than any other document of the new feminism.

Image: In person, Ingrid Bengis is even more intense than her book and surprisingly shy considering how intimately she reveals herself in its pages. “I was not involved in the women’s movement,” she says, “and although there are many things I sympathize with, I am very wary of conclusions that precede experience. It is just as easy to rest upon a contemporary image of ourselves as determined by the movement as it once was determined by our mothers.”

The daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants to New York, Ingrid Bengis grew up with a taste for Russian literature that parallels one of her ideas today—that women, in the process of realizing their potential, are far more interesting than men. “In every conversation I have with a man I ask myself, ‘What am I getting out of this?’ What’s missing is the growing part. With women it’s a vivid force, comparable to what took place in Russian literature in the nineteenth century. The female characters are complex, rich, vivid. The man is the superfluous man; he’s drifting, doesn’t have a focus.”

Ms. Bengis has had emotional and sexual relationships with women, but in this as in everything else she is responding to her own sense of the problem of being human. “Look,” she says, “I feel very tentative about all of these things. With a man the process of exploration is closed—either you end up in bed or get married. With another woman you don’t know what to expect, you have to invent it. There are mixtures of shyness and aggression: every possible emotional blend is granted a kind of respect that derives from uncertainty. I am impatient with women who are cold or insensitive and when I encounter men’s awareness I am moved by it. It sounds strange to hear myself saying these things—it’s like admitting to being a bigot.”

Ingrid Bengis dropped out of Brandeis after a year and a half and toiled as a file clerk, a waitress and a documentary film production secretary, until finally she hit on her favorite job—driving a cab. “I loved driving and talking to people,” she recalls. “Sometimes they’d look into the cab and say, ‘Oh, it’s a woman. Well … I’m in a rush.’ I’d say ‘I’ll get you there!’ and I’d feel like Superwoman and take off flying. I’m a damn good driver. I enjoyed proving it.”

Sills: Today Ms. Bengis drives between a tiny apartment in New York City’s Little Italy and a small house in Maine, which is becoming another proving ground of sorts. At her Maine house Ingrid Bengis chops the wood and does all her own carpentry. Recently she jacked up the entire house, axed out the sills and changed the foundation herself. “I just went down to the hardware store in town and asked them how to do it step by step,” she explained. “I enjoy a sense of my own physical powers.”

To write the book she went into complete seclusion in Maine for eight months, and her sense of apartness is perhaps what distinguishes Ingrid Bengis from other women writing in and around the movement today. “The only thing I’m militant about is the necessity for struggling to be as fully human as we can,” she says. “What’s really going on won’t come out in words, yet I love words. In writing I direct my energies to bringing words as close as I can to the bare bones of experience.” She pauses thoughtfully. “Life is a powerful, terrifying business.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments