Original Publication: Newsweek – March 26, 1973

An exotic, international game of chance took place recently in Montevideo, Uruguay, where American publishers spent ten days bidding hundreds of thousand of dollars for book rights to a harrowing true-life adventure. Survivors of the October plane crash in the Chilean Andes – headlined around the world because they ate the flesh of their dead comrades – appointed four young friends who coolly conducted an auction to sell the story. Doubleday offered six figures plus the services of author Gay Talese – but this wasn’t good enough for them. The winner was J.B. Lippincott Company, which reportedly bid between $400,000 and $500,000, with novelist Piers Paul Read to do the writing.

Lippincott immediately made a deal with the Book-of-the-Month Club for more than $100,000 for book-club rights, then sold more than $400,000 worth of serialization and European rights, and will soon auction U.S. paperback rights. So far not one word of the book is written, but by the time the paperback deal is made, Lippincott should be holding more than $1 million worth of “subsidiary rights” to the book.

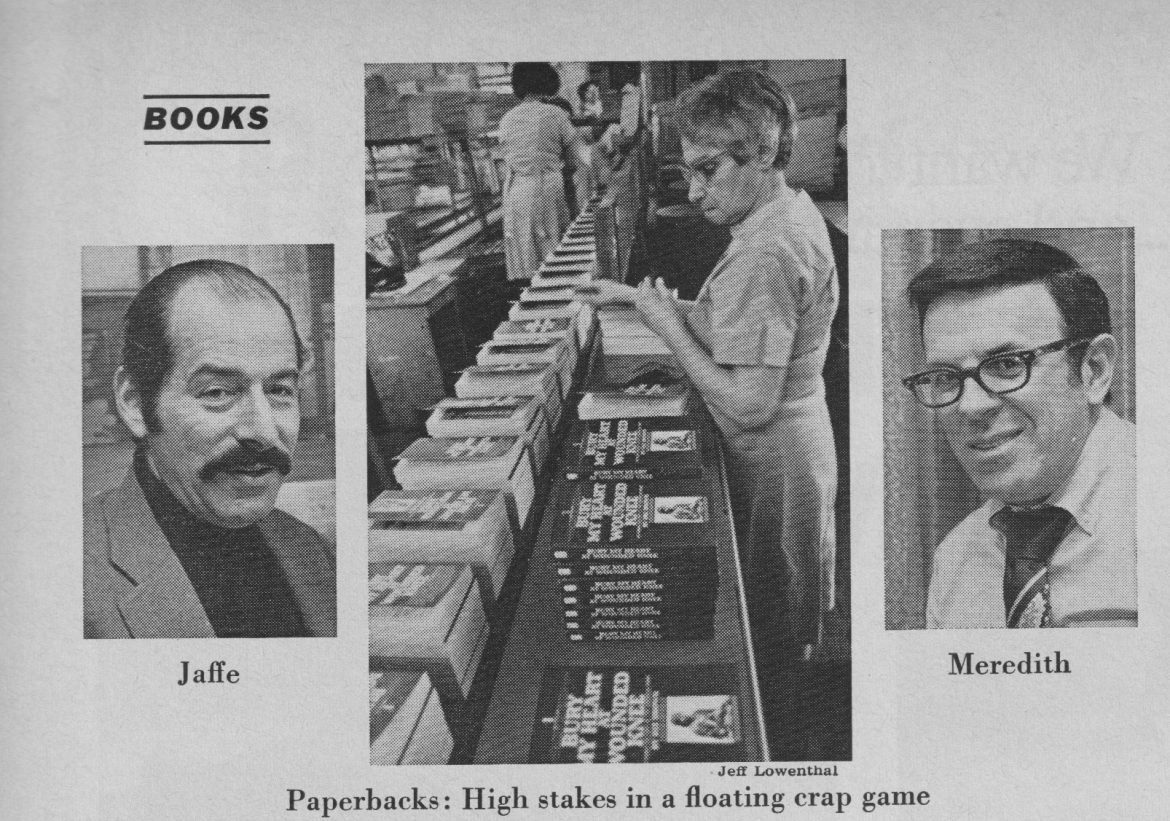

Almost all the important money in hardcover publishing today is in subsidary rights, and the competition has turned the once gentlemanly business of publishing into an enormous floating crap game. Seven or eigth major reprint houses (many financed by big congloerates), a few big book clubs and twenty or 30 hardcover publishers control the stakes. Bids of hundreds of thousands of dollars are routinely passed back and forth over the phone, and a major house can be bidding on four or five books at once.

“I’m O.K.—You’re O.K.,” the guide to transactional therapy, was sold to Avon Books for $1 million. Avon, owned by the Hearst Corporation, then topped all previous paperback prices by paying $1,100,000 for the current publishing phenomenon, “Jonathan Livingston Seagull”: Avon says it grossed that much the first day of sales. Bantam Books just bought Rose Kennedy’s memoirs sight unseen for a reputed $700,000 and Warner Paperback Library put up $700,001, before publication for Robert Crichton’s mildy best-selling novel about a nineteenth-centure Scottish family, “The Camerons.” Holllywood figures and razzle-dazzle hype have invaded U.S. publishing.

Search: “In 1964 ‘The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich’ went for $400,000 and everyone thought that was outrageous,” William Ewald, editorial director of Pocket Books told NEWSWEEK’s Maureen Orth. “Now it’s reeling out of control. There has never been such a search on for people who can write well.” Maybe, but the net effect of big-money book deals has been to treat books not as art or even craft but as commodities. “Publishers are often forced to buy books from one- and two-page outlines,” Says Richard Snyder, executive vice president at Simeon and Schuster. “You can’t tell whether they’re going to be quality-written or not.”

Meanwhile, the rich authors are getting richer and the poorer ones want a piece of the action. Celelbrity writers like Jacqueline Susann, Philip Roth and Irving Wallace negotiate up to seven-figure prices for their paperback rights. And instead of the usual 50-50 split with hardback houses, they demand and get 100 per cent of all subsidiary rights. But now even writers with only one successful book to their credit are demanding the same privileges, and they pose a threat to smaller publishers who relay heavily on the income from subsidiary rights. “Publishers like us will have to invest in young authors and hope to make that work through success and loyalty,” says Allan Lang of Viking. Even the concept of what constitutes a best seller is altered. “If a book sells a million copes it’s a best seller,” says Leona Nevler, publisher of Fawcett’s Crest-Premier Books, “but if you pay $700,000 for it [as Fawcett did for “The Best and The Brightest”], you’re stuck. You just break even at a million copies.”

“Big money is definitely changing the business,” admints Peter Mayer, publisher and editor in chief of Avon. “Fewer writers, agents, publishers are content to deveop gradually. Not too many great things get produced that way.” Some writers themselves feel that getting rich quick does little to enhance their craft. “I consider this whole absurd sweepstakes frightening,” says Larry McMurtry, author of the current best-selling paperback “All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers.” “It hurts authors to have a lot of money, particularly when they are developing.”

Decline: The search for the pot of gold cuts down on literary risk-taking. “We’re all a little more conservative, a little less pioneering,” says agent Scott Meredith, who first started literary auctions and whose agency moves 6,000 properties a year. “We all take on new writers,” add Meredith, “but it’s harder to get a first novel published today.” And as the stakes get higher, there has been a decline in careful line-by-line editing. The editing editor has become less important than the acquisitions editor who digs out and promotes new properties.

In fact, with subsidiary rights apparently controlling American publishing right now, the future of the hardcover book is in doubt. Paperback houses are publishing more originals, and some publishers foresee a day when only a few hardback versions will be offered for libraries, collections and institutions. Agent Peter Matson says flatly: “Anybody who specializes in hardcover publishing is doomed. Hardcover will not last the decade.” But Marc Jaffe, senior vice president and editorial director of Bantam Books, which has pioneered in the field of the fast, topical paperback, insists that “we definitely need hardcover publishing. It should be strengthened.”

At the moment, the chief function of hardcover seems to be what Michael Korda, the dynamic editor of Simon and Schuster, calls the “filter” through which manuscripts percolate to become hot properties. “I like gambles,” says Korda. “If I can buy a manuscript for $3,500 from a writer and, through promotion, book clubs, reviews, create a $350,000 property, the author is excited and happy – and so am I.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments