Original Publication: Newsweek – Special Issue – The Arts in America December 24, 1973

Pop: Messiah Coming?

I’m not going back to Woodstock for a while

Though I love to hear that lonesome hippie smile.

I’m a million miles away from that helicopter day –

No, I don’t believe I’ll be going back that way.

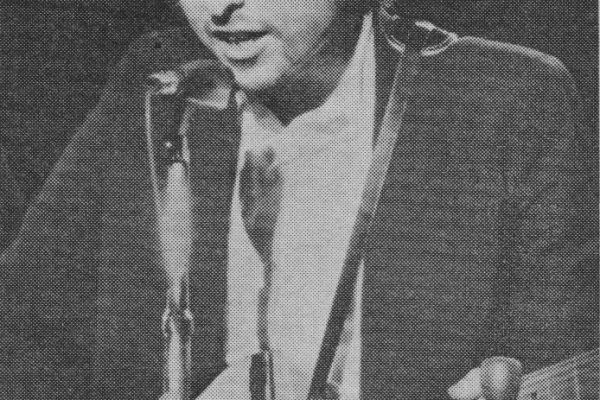

A dirty linen jacket thrown over his carefully patched blue jeans, rock superstar Neil Young sang an elegy to the long-gone days of Woodstock at the opening of The Roxy, a chic new rock ‘n’ roll nightclub on Los Angeles’s Sunset Strip. Peering through violet-tinted glasses at the crowd – a mix of eager teeny-boppers and blasé recording executives – the millionaire singer muttered, “Welcome to Miami Beach.” As a further ironic gesture toward the flash and theatricality that have taken over rock music, Young hung a dozen painted and spangled high-heeled boots from the band’s grand piano.

Meanwhile, in a recording studio on a dingy West Side street in Manhattan, singer-songwriter Carly Simon, seven months pregnant, was rehearsing her new album. One number commented on the current state of the record industry:

There are too many phonograph records out,

I think I’ll have a baby.

The 60’s are over, and nowhere is it more evident than in the world of popular music. In the astonishing creative outburst of the 60’s, pop became rock and dictated the rhythms of a generation. Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix electrified and amplified the basic black and folk roots of American popular music. Rock resurrected the blues, dealt a temporary death blow to jazz, taught country singers to plug in their gee-tars and buried Tin Pan Alley forever. To a generation turned off by war and turned on to drugs, rock was the catalyst of a whole new life-style.

Rock changed the way youth related to authority, to learning, to sex and to government. “For a long time, America has been selling out,” wrote Douglas Kent Hall in a preface to a book about rock stars. “Rock culture and its minstrel heroes are seeking something better.” But the search was also laced with violence and self-destruction. Young idols like Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Brian Jones died directly or indirectly from drugs. Thousands of other believers were permanently scarred by bad trips.

Today, the minstrel heroes have been swept from the streets and into the corporate headquarters of huge conglomerates where they sign contracts worth millions of dollars. Rock has bounced off the barricades, split in a hundred different directions and converged into a new pop mainstream packaged as pure entertainment. Only one heavy message still prevails – pop music is big business. And right now the business, in a lull for the first time in a decade, is anxiously waiting for a new messiah to come along – just as Elvis did in the ‘50s and the Beatles did in the ‘60s – to give the recording industry a nice, swift kick into a brand-new era. “We hope this marvelous genius will come out,” says Mo Ostin, chairman of the board of Warner Bros. Records, “but he hasn’t emerged yet.”

Nobody knows where the new genius is coming from, but the talent search is on and the stakes are enormous. Pop music is America’s most pervasive art form. It wakes us up in the morning. It rides along in our cars. It accompanies us through the bars, supermarkets and bedrooms of our lives.

Nobody knows where the new genius is coming from, but the talent search is on and the stakes are enormous. Pop music is America’s most pervasive art form. It wakes us up in the morning. It rides along in our cars. It accompanies us through the bars, supermarkets and bedrooms of our lives.

Last year in the U.S. the retail sales of records and tapes amounted to $2 billion. That figure tops the movies by a whopping half billion and doesn’t even take into account the millions more realized from live concert appearances. Rock impresario Bill Graham estimates that the historic 21-city “comeback” tour Bob Dylan will undertake with The Band next January will gross $5 million. Columbia record labels provided CBS with 33 per cent of its net profits in 1972 – even after paying the inflated expense accounts of those fired as a result of the payola scandal. And the three record companies of the Warner Communications conglomerate racked up profits after taxes last year of $23.8 million, compared with $15.8 million earned by Warner’s entire film and feature division. In less than a decade pop music has become America’s most commercially successful art form.

But the explosive growth that began in the ‘60s has slowed somewhat, and many critical listeners feel the quality of the music is increasingly bland. To keep the momentum going, the record companies, while riding out the still unresolved payola scandal and awaiting the messiah, continue to produce a plethora of what they call “product.” This ranges from nostalgia – the Pointer Sisters scatting songs from the ‘40s and ‘50s, Fats Domino peddling his “golden oldies” on TV – to the amazingly popular “decadent” rock, in which Alice Cooper, the queen of rock ‘n’ rouge, chops off the heads of rubber baby dolls, Iggy Pop flagellates himself, and the ultra-decadent New York Dolls, in outrageous bisexual drag, just stand there looking like mutants visiting earth from outer space. Wedged between the regression of nostalgia and the perversity of deca-rock is the real core of the pop product – the myriad soft and hard rock bands, and the individual singer-songwriters, both black and white.

Since rock has become big business there has inevitably been a clash of artistic and commercial values. An inordinate number of records is being released, artists are lost in the shuffle, and the product is often mediocre. “It’s heartbreaking when you put so much work and love into your art and then somebody walks right over you like you don’t exist,” says a promising young singer who’s been on three record labels. “Every time you join with a company they promise you tours and promotions which don’t happen. After you’ve signed, the top people won’t even talk to you. If you’re not going to bring any money in, they’re not that interested. They use a loser for tax write-offs.” And Joe Smith, the dynamic president of Warner Bros. Records, frankly admits: “I wish we weren’t owned by a big conglomerate. We’d prefer saying let’s not grow this year, let’s not make any more money, but the pressure is on to keep trying.”

The competition is fierce. Radio airplay is the single most important ingredient in selling a new song, and current “Top 40” play-lists on AM radio are actually down from 40 singles to around 27 or even twenty. The result is that fewer new artists are getting heard. “The record business is unique because the consumer gets to judge the product before buying it”, says Lou Adler, owner of Ode Records and producer of Carole King and Cheech and Chong. “When Top 40 rules the market it’s unhealthy.”

The competition is fierce. Radio airplay is the single most important ingredient in selling a new song, and current “Top 40” play-lists on AM radio are actually down from 40 singles to around 27 or even twenty. The result is that fewer new artists are getting heard. “The record business is unique because the consumer gets to judge the product before buying it”, says Lou Adler, owner of Ode Records and producer of Carole King and Cheech and Chong. “When Top 40 rules the market it’s unhealthy.”

A few years ago the so-called underground FM stations, which played long album cuts and even whole albums, promised to break the stranglehold of the Top 40 AM stations with their requirement that a song not be longer than two and a half minutes. But lately, while AM has started to vary its programming, FM is jammed with advertising and is considerably less innovative. “It’s a very risky business,” says Anthony Hoffman, a financial analyst who studies the recording industry. “The peak demand for a record lasts from six to twelve weeks. Records are a perishable product like butter and eggs. The advantage with butter and eggs is you know what the demand will be. With records you simply have no idea how they’ll go over.”

To many record people the risks are exhilarating. The business is filled with high rollers who love the kind of life that asks: “Will it be a hit or a miss?” Pete Marino, a flamboyant, fortyish former promotion man for Warner Bros. Records, is both nostalgic and decadent. When he was recently let go after thirteen years with the label, he had to decide first what to do with the big “WB” tattooed on his arm. The problem was solved when he got a new tattoo right underneath the old one. It says, “That’s all, folks.” Now Marino is making his own records and has signed his first two acts: the cable-car-bell-ringing champion of San Francisco and the girls who sing during half time at the 49er football games.

Actually the sheer size and success of the pop product have given rise not to one huge audience, but, as with films, to many differentiated audiences. Teenagers who buy the blasting, raunchy, primitive sounds of bands like Deep Purple and Teenage Lust, which are scorned by rock critics, are not turned on by the softer, more intellectual moods woven in the work of a performer such as Joni Mitchell. A band like Black Oak Arkansas is one of the South’s hottest acts and makes most of its impact below the Mason-Dixon line. Yet black soul music, which used to be confined largely to the ghetto, has crossed over to suburbia.

Thanks to the musical genius of singer-composers like Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder and the big-selling scores of black movies like Isaac Hayes’s “Shaft” and Curtis Mayfield’s “Super Fly,” black music right now is dominating the Top 40 play-lists. Then there is a whole slew of performers who write and sing what is essentially country, blues or even classical material, but all have been influenced by rock. “Rock began as music by the inept for the untutored,” says Jerry Wexler, executive vice president of the Atlantic Recording Corp. “Today it has become as sophisticated in virtuosity and harmonic expression as classical music.”

Not only is the general level of musicianship in rock higher than before; so is the level – at least the energy level – of entertainment. Spurred by late-night TV rock shows such as ABC’s “In Concert” and NBC’s “Midnight Special,” which emphasize the visual side of the music, and by today’s audiences, who tend to be bored with bands that just stand up and play, pop performers are adding elaborate theatrics to their acts. English performer Elton John, one of today’s most successful superstars, is known as the Liberace of soft rock. While he sings space-age fairy tales like “Rocket Man” and “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” he flips, flops, scrambles and screams over seven pianos. Offstage John appears in 8-inch Day-Glo platform shoes, “outasight” heart-shaped spectacles, a $40,000 diamond watch, and various ruby, sapphire and diamond pins and necklaces from Cartier. “Rock stars are the glamorous movie stars of today,” says John. “We’re the ones everybody talks about. I think we should look the part.”

It’s true that rock stars, with their fleets of limousines and gaggles of groupies, do occupy the Plaza suites and Beverly Hills Hotel bungalows much like the movie stars of old. They make so much money they’re the new aristocracy of the entertainment world. Freaks like Alice Cooper, who scare the daylights out of parents who can’t even tell what sex their kids’ idols are, are running around with carefully managed real-estate investments and pension plans. But Alice has plans for the movies too. “I want to be the great American villain just like Bela Lugosi,” declares Alice. “Actually I think he was a romantic because even when he bit girls on the neck they always went ooh and aaah.”

Maybe more rock stars ought to plan ahead like Alice. Warner’s Joe Smith says that because of “future shock and the intense glare of the media,” most acts stay at the top only three years. Generations are three to five years now,” says Smith. “Every generation needs its own idols.”

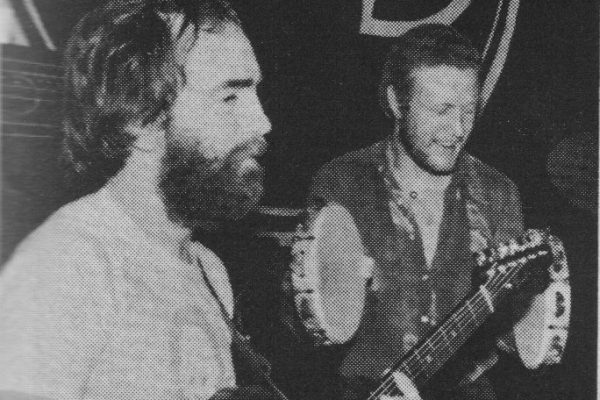

Anybody’s list of current idols has to include the Allman Brothers. They were the one true hard-rock band to achieve superstardom this year. They played at the gigantic Watkins Glen concert, which drew 500,000 fans, and both their album, “Brothers and Sisters,” and their single, “Ramblin’ Man,” were No. 1 on the charts. Visually unassuming, they may be the last of the pure stand-up-and-play bands. From Macon, GA, the Allmans are a closely knit Southern tribe whose tight, driving sound owes a lot to the blues, jazz, country and the hard red clay soil of their home state. Led by golden-haired Gregg Allman, 26, the lead singer who plays the organ and guitar, and Dicky Betts, the virtuoso guitar picker, the Allmans worked hard to make it to the top and can’t see themselves fading in three years. “Either you wear out or your music wears out,” says Gregg, “but we’re sure gonna hit it as hard as we can for as long as we can.”

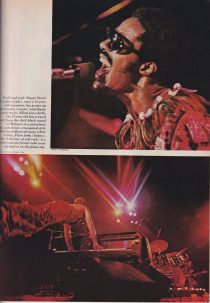

Stevie Wonder is a true prophet who’s been hitting it since he was 12 years old with songs like “Uptight” and “Signed, Sealed, Delivered.” According to another hit-maker, producer Richard Perry, “he’s our most important contributor now.” Blind since birth, Wonder, now 23, quit his original label, Motown, briefly when he turned 21. Wanting to make his own kind of music, he created a milestone LP, “Talking Book,” for which he not only wrote and sang all the songs himself but also played most of the instruments, including the Moog and Arp synthesizers. “Talking Book’s” songs, such as “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” and “Superstition,” stress Wonder’s intense love of people and life. On his latest album, “Innervisions,” he has written some haunting songs about the sufferings of blacks.

Wonder is presently recovering from a near-fatal auto accident that he says has brought him to yet another musical crossroads. “I do believe it’s time for a change,” he says. “I’m more aware of putting time in its perspective. I’ve been listening a lot to what’s happening in Egypt and Chile. The world may be going into another Dark Age.”

Pop music is still a long way from the Dark Ages. But 1973 has been a very rough year for the music business. The payola scandal broke and nobody knows its outcome. There’s a critical shortage of one of the main ingredients that goes into the making of records – vinyl. The fuel shortage prevents acts from hauling their heavy equipment around. And New York’s Sen. James Buckley has attacked the recording industry for glorifying the use of drugs.

Musically, pop has failed to break through to any new creative dimensions. What is discouraging is to hear great groups like The Band resort to mediocre and self-indulgent nostalgia as they do on their new album, “Moondog Matinee.” Pop music people are eagerly awaiting Dylan’s comeback on the concert trail as the most significant musical event in years. Nostalgia is nice when people need to look back, but it can’t be mistaken for creativity.

The man who first predicted the nostalgia boom in pop music, promoter Richard Nader, has a theory that it’s the fourth year of every decade that determine the music of the decade. “Elvis burst on the scene in ’54, the Beatles in ’64,” he says. What does Nader see of ’74? “Clockwork Orange,” he replies.

There may be more truth than poetry in Nader’s crack. Certainly the 13- and 14-year-old weeny-boppers who hang out at Rodney Bingenheimer’s discotheque in Los Angeles looks like some future vision of the apocalypse. They were just babies when President Kennedy was assassinated. They grew up with bad drug trips and the Vietnam war as a daily TV serial. And now, as they mature, there’s Watergate.

If pop music is the most spontaneous reflection of our lives and times, no wonder it presents such a confused spectacle. Bing Crosby crooned for a simpler time that wanted a white Christmas and pennies from heaven. Sinatra sang for a time that wanted the witchcraft of romance after the weariness of hot and cold wars. Dylan warned us that something new was blowing in the wind. The minstrels of Woodstock chanted anthems of togetherness and protest. And now we hear a scattered symphony – love, soul, peace, and give me my percent of the take.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments