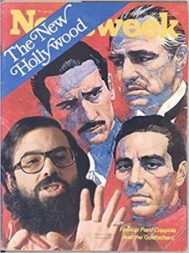

Original Publication – Newsweek – November 25, 1974

“Give me a minor chord, Nino.” Seated at an editing machine in Rome, director Francis Ford Coppola is scoring reel 23, the final reel of “The Godfather Part II,” with Nino Rota, one of the masters of movie music. As the last images flicker, Rota starts to play the haunting “Godfather” waltz theme at the piano, and Coppola speaks of what he’s tried to do in his unprecedented, two-film, nearly seven-hour epic which will be completed when the long-awaited sequel is released next month. “I want to show how two men, father and son, were born into the world innocent,” he says, “and how they were corrupted by this Sicilian waltz of vengeance.” Rota plays a final chord, and Coppola says, “Just so there will never be a Part III, give me one more bong.” Rota bongs. “It’s over,” sighs Coppola. “If the audience doesn’t walk out crying, I’m going to cry.”

It’s doubtful whether Coppola or anyone connected with “Godfather II” will be crying – except perhaps tears of pure venal joy. The original “Godfather” has grossed a mind-boggling $285 million-plus; and last week Coppola himself introduced the film to an estimated 90 million people on NBC, which paid a reported $10 million for a one-time-only showing. Already the sequel has the largest advance rental guarantee of any film in history – more than $28 million. (Coppola gets 13 per cent of the gross.” And “Godfather II” is almost certain to repeat the critical raves that hailed the original as that rarely achieved ideal in a schizoid business split between art and commercialism – the big-grossing film that is also a classic of craftsmanship, seriousness and entertainment.

This evasive trophy is the Holy Grail of the film industry, and, by acclamation, Francis Ford Coppola has found it. At 35, Coppola stands alone as a multiple movie talent: a director who can make the blockbuster success and the brilliant “personal” film, such as his powerful study of electronic eavesdropping, “The Conversation”; a superb writer whose script for “The Great Gatsby” escaped the general obloquy heaped upon that film; a shrewd and beneficent discoverer and developer of young talent; and a sound businessman respected by every iron-fisted budget squeezer in Hollywood. “Francis exudes an aura of boyishness,” says John Calley, incoming president of Warner Bros., “but he’s one of the most sophisticated production people around. He has that very rare mastery of both high- and low- budget filmmaking.”

Ironically, this black-haired, black bearded fair-haired boy is no cool human computer but a volatile, passionate sensibility very much aware of the pressures upon him. “You know what it’s like to be a director?” he asks. “It’s like running in front of a locomotive. If you stop, if you trip, if you make a mistake, you get killed. How can you be creative with that thing behind you? Every day I know it’s $8,000 an hour. It forces me into decisions I know will work. I can’t afford to take a chance.”

Yet Coppola is a gambler who lives to take chances. He has shunned Hollywood to live in San Francisco, where he’s developing his own mini-arts empire, centered in the Coppola Co. He pushed the introverted 30-year-old director George Lucas to write “American Graffiti” and lent his name to the project as producer after the script has been turned down by eleven studios. “Graffiti” is on its way to grossing $85 million. Actors Al Pacino, James Caan and Karen Black all got their first big movie breaks from Coppola. Not only was Marlon Brando’s star reborn in “The Godfather,” but both Pacino and Robert DeNiro will undoubtedly emerge from “Godfather II” as the two hottest young talents on the screen today.

And in his most daring and significant move, Coppola has begun to acquire the means of distribution for his own and other films, thereby undercutting the chief power the major studios still hold. Unsatisfied by conventional success and chafing under the present system, Coppola is out to become the first truly successful artist-mogul, thereby setting up an alternative to the system by which the movie business has always been run.

It was to help further this aim that Coppola agreed to do a sequel to “The Godfather” – that and the challenge to top the untoppable. The deal he got from Paramount enabled him to become “my own subsidy,” to establish his own film company based on the people he admired. And, he admits, he loves the power: “Imagine having millions and millions of people all over the world sit in a room and totally surrender their brains to you for two hours. What would General Motors pay to have that? So I thought that maybe I could take this popular art form and escalate it one notch – put out tough ideas about the character of violence and turn the myth back on itself. The same principles that drive a gambler drove me.”

Coppola’s gamble has paid off. “Godfather II,” even without Marlon Brando, is just as exciting and far more ambitious than the first “Godfather.” A juicy, old-fashioned melodrama staged on a grand operatic scale, it features stunning performances, spectacle, and Nino Rota’s richly expressive score. Coppola also pulls off the technical feat of telling two stories simultaneously. Moving both forward and backward in time, “Godfather II” picks up the career of Michael Corleone (Al Pacino), the young king of the mob that is now so established as Big Business that it buys U.S. Senators like used cars. Interwoven with Michael’s rule of money and blood are flashbacks of his father, Vito, played by Brando in the original and here played as a young man by Robert DeNiro. Speaking in Sicilian dialect (with subtitles), DeNiro falls afoul of the Mafia in Sicily, flees to New York, and slowly rises to the portentous power of the Godfather.

For “Godfather II” Coppola had twice as big a budget ($13 million) as for the original, and he used it like a master painter being given his first huge canvas. The social texture of the film is denser and more complex, and Coppola stages vivid episodes in Havana during the fall of Batista, swarming festivals in New York’s Little Italy, a Senate crime-committee hearing. Again there are large helpings of his shocking, gory, but strangely dispassionate violence – a violence that seems to rebuke itself with its own grim melancholy.

Coppola shot the film in nine months on various locations – Tahoe, Las Vegas, New York, Washington, Trieste, Sicily and the Dominican Republic. He thinks of the two films as one giant whole, and even went so far as to use the same extras. A fascinating new character with a major role is not Italian but Jewish. “Everybody knows there are a lot of Jews in the Mafia,” says Coppola. Hyman Roth is closely patterned after organized-crime figure Meyer Lansky and is portrayed marvelously by Lee Strasberg, the legendary director of Actors Studio – in his first formal acting role in 40 years.

In typically Hollywood fashion, Paramount both lusted after a new “Godfather” and was leery of it. “Paramount never took an official vote to back the movie,” says Coppola. “Everyone was terrified of it. They just kept authorizing money until there were 200 carpenters on location. I spent $1 million before I had a page of script written.” When Coppola did finish the script, with “Godfather” author Mario Puzo adding a few touches, Pacino wasn’t satisfied. So Coppola rewrote the entire script in three days. Copies for the first actors’ reading emerged from the Xerox machine with an hour to spare before filming started. When they read the script, the actors stood and applauded Coppola.

Accolades follow Coppola wherever he goes these days. His intelligence, talent and sophistication have not effaced a boyish ebullience (“239 pounds of fun,” he says) that allows him to enjoy his status as the hot property. His current life is itself like a wacky movie about the new – and old – Hollywood.

FADE-IN: A New York office building, Coppola emerges from his first board meeting since he acquired nearly 10 percent of the stock at Cinema 5, the film distribution company that owns eleven elegant theaters in Manhattan. “Yippee! That was easy!” he says. He persuades Donald Rugoff, president of Cinema 5 to change the name of the company to Cinema 7, because it is his lucky number. “Bergman is very high on you, Francis,” say Rugoff. “He’s interested in giving his films to us,” “Good,” say Coppola. “Try for Kubrick.”

DISSOLVE TO: Coppola’s lavish Art Deco apartment in the chic Sherry-Netherland Hotel. Dino De Laurentiis, the duce of independent producers, arrives. He wants Coppola to direct a new film, “King of the Gypsies.” The story is not unlike “Godfather,” although De Laurentiis denies this vehemently. “They’re alike only in one respect,” he says, “box-office potential! I say this not because he’s here, but no one but Francis Coppola could make ‘The Godfather’ more than just another gangster picture.” And the diminutive De Laurentiis adds earnestly, “Look, Francis, the only way to do business is to screw the major studios,” Coppola replies: “Dino, you should be the Godfather.”

CUT TO MONTAGE: Coppola races through London, Paris, Rome. In every city the biggest distributors are dying for a piece of his action. Can they buy into Cinema 5? Can they distribute his next film? Would he like some help in financing his projects?

DISSOLVE TO: Rome, an actors’ club. It’s Coppola’s last night in Rome, and he’s having dinner with Federico Fellini and his wife, actress Giulietta Masina. At dinner, Coppola, whose father was first flautist with Toscanini’s NBC Symphony, charms Fellini by singing the theme music to all Fellini’s films. Later the great Italian director, who despite his international reputation still has to battle with producers for financing, says to Coppola: “So, they tell me you have become very rich.” Coppola looks pained and answers, “It’s not that great. After you reach a certain level money just brings problems.” Fellini, who’s selling his villa to pay his taxes, looks as if he’d like some of those problems.

Coppola is tremendously ambivalent about his material success. “I’m at a Y in the road,” he says. “One path is to become a manager and an executive who brings about great changes. On the other, there’s a very private notion to put my energy into developing as a writer and an artist. In the next five years I want to break through creatively by my own standards. I don’t think any film I have made even comes close to what I have in my heart.”

Coppola has been deeply influenced by his wife, Eleanor, an artist, and by his older brother, August, a writer and professor of literature. Neither is much impressed with his fame or wealth. Yet Coppola, with his Havana cigars and his private plane, lives flamboyantly.

The newly refurbished Pacific Heights mansion in San Francisco, where he lives with Eleanor and their three children, is a miniature fun palace containing a ‘30s jukebox, a portrait of Mao, a life-size video screen at the foot of his bed and a fully equipped film theater. He’s in the process of buying a choice block of real estate across the street from the headquarters of the Coppola Co., a beautiful, partially restored 1906 triangular building topped with a baby blue cupola. Coppola throws lavish dinner parties, but most of all he loves to cook pizza for pals on Sunday nights in a North Beach restaurant.

At the Coppola Co., his production control center (he also owns American Zoetrope, a technical facility for editing and mixing, a theater and 83 percent of a magazine), the employees are called “the family.” They are a mixed bag of individualists not typical of the film industry and Coppola gives them their freedom. “The most crucial decision in filmmaking,” says Walter Murch, a Coppola editor-writer, “is whom you hire. Once Francis decides that, he steps back except to make special decisions. He gets a diversity of ideas, performances and textures he wouldn’t get if everything came out of him.” “I’ve never been involved with yes people,” says Coppola. “My closest friends always criticize.”

Coppola’s current goal, he says, is to become a character from the opera “La Boehme.” Mornings he will write in his tower – presently under construction at the top of the Coppola Co. building. The rest of the time will be given over to rehearsing and directing theatrical plays, radio plays and scenes from his upcoming movies with his own acting company, both in his theater and on location where he’ll make his films in 16 mm. Community participation will be welcome, the activities to be announced in his magazine, City. At the end of the day he will hold sway in his outdoor cafe, basking in the wit of intelligent friends and surrounded by beautiful women. “Their presence is enough – almost,” he says

Young beauties didn’t flock to Coppola when he was growing up. “I was funny-looking, not good in school, near-sighted, and I didn’t know any girls,” he says. “My mother called me the affectionate one of the family. My older brother was handsome, brilliant, the adored one of any group. I really took up writing to imitate him.”

When he was 14, Coppola made his first film. He cut up the family’s home movies to recast himself as the hero. But the seeds of creativity were planted earlier. When Coppola was 9, he contracted polio and had to stay in bed for a year. “I played with puppets, watched television and read comic books,” he recalls. “I got immersed in a fantasy world. The popular kid is out having a good time. He doesn’t sit around thinking about who he is or how he feels. But the kid who is ugly, sick, miserable or schlumpy sits around heartbroken and thinks. He’s like an oyster growing this pearl of feelings which becomes the basis of an art.”

Coppola’s father, Carmine, was constantly moving the family from Long Island to California while he looked for a break as a classical composer. By the time Coppola finished high school he had attended 24 different schools. It wasn’t until his last two years at New York’s Hofstra College that Francis shed his mild-mannered ugly-duckling image and became “Joe Dynamite,” ace director of school plays.

At the UCLA film school, Coppola won the Samuel Goldwyn writing awards, which landed him, at 22, a staff writer’s job with Seven Arts. At 23, he married Eleanor, who is three years his senior. They met while he was doing a picture in Europe for producer-director Roger Corman, king of horror movies, who has given a start to many Hollywood notables, including director Peter Bogdanovich. At 24, Coppola co-wrote the screenplay for “Patton” for which he won an Oscar.

Coppola became the first film-school graduate the Hollywood establishment took a chance on. His master’s thesis film, “You’re a Big Boy Now,” was a free-wheeling farce with one of the first rock scores. Then Warners offered him a musical, “Finian’s Rainbow.” It flopped and Coppola next made a very personal film called “The Rain People,” a story of a pregnant woman who leaves her husband, although she loves him, because she doesn’t want to be married – a film ahead of its time.

On location in Nebraska for “The Rain People,” Coppola decided not to go back to Hollywood. In 1969, he made a deal with Warners to set up his own company, American Zoetrope. “Francis could sell ice to the Eskimos,” marvels George Lucas. But Zoetrope was a personal and financial disaster for Coppola. Slated to do “high-class low-budget movies” at the height of the “Easy Rider” youth-picture craze, Zoetrope was a mecca for radical young filmmakers. But Warners hated Zoetrope’s first project, the futuristic “THX 1138” directed by Lucas. They cancelled their deal and Coppola found himself $300,000 in debt.

“It looked as if we would never make another movie again,” says Lucas. Coppola had gotten five offers to direct films he didn’t like. “One was a cheap gangster movie budgeted for $2 million based on a book about to come out,” remembers Lucas. “Francis said no.” But one night Peter Bart of Paramount called, again asking Coppola to direct the cheap gangster movie – “The Godfather.”

Coppola put his hand over the receiver, relates Lucas, and said “George, what should I do? Should I make this gangster picture or shouldn’t I?” “Francis, we need the money,” Lucas told him. Coppola told Bart, “OK, I’m in.”

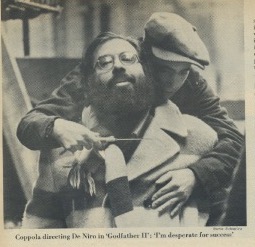

Many movie people were surprised that after the incredible triumph of “The Godfather” Coppola came out with a small, serious picture like “The Conversation.” “I’m desperate for success,” says Coppola, “and for people to leave the theater saying mine was the most wonderful movie they ever saw, but I won’t resort to the 22 sure-fire scenes every director knows to do it.” Coppola would rather probe ideas. One of his strengths as a filmmaker is his ability to draw the audience into other people’s worlds. In “The Conversation,” wiretapper Harry Caul has stripped his own identity down to near-zero, living on the shreds of other lives he picks up on his earphones. Is there something of Caul in Coppola? “Francis is an emotional voyeur,” says Al Pacino. “He looks, he sees, he watches people’s emotions. He can’t help it.”

Taking his fortune at its high tide, Coppola is going to bet his last dollar on himself and his talent. He is going to risk millions in the next eighteen months to produce four commercial films and attempt to distribute them worldwide without the help of a major studio. Two will be his own movies and two will be directed by others. His first will be “Tucker,” which he describes as “a tragic comedy” about Preston Tucker, the designer of the Tucker automobile, who went bankrupt in 1949 after a government investigation of his financing. He’ll also write one of his “personals” – the story of twins, a boy and a girl – as a way of exploring the male-female duality in every individual.

In addition he’ll serve as executive producer on “The Black Stallion,” a romantic adventure to be directed by Carroll Ballard, a UCLA classmate who Coppola predicts will be “a famous director in three years.” And John Milius, the controversial young writer-director (“Dillinger”), will direct his own macabre script about Vietnam, “Apocalypse Now,” for the Coppola Co. “The whole idea is to go counter to the Hollywood system,” says Ballard. “If you accept their money you have to accept their procedures and their motives.” Ballard acknowledges the Coppola people are on a tightrope. “Francis is a big man now,” he explains, “but he’s a flea compared to the establishment.”

Will the flea bite the elephant or the dust? Coppola doesn’t know, but true to form he has an answer. “Every year there’s a hot director,” he says. “And if he falls from grace with the critics or the public the next year, he often loses his balance and confidence in his own talent. I’ve lived in a state of anxiety the last twelve years. I was terrified of ‘The Godfather’ I was terrified of ‘The Conversation.’ But I want to keep rocking the boat. Taking chances is what makes you strong, makes you wise.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.