Original Publication — Newsweek: January 6, 1975

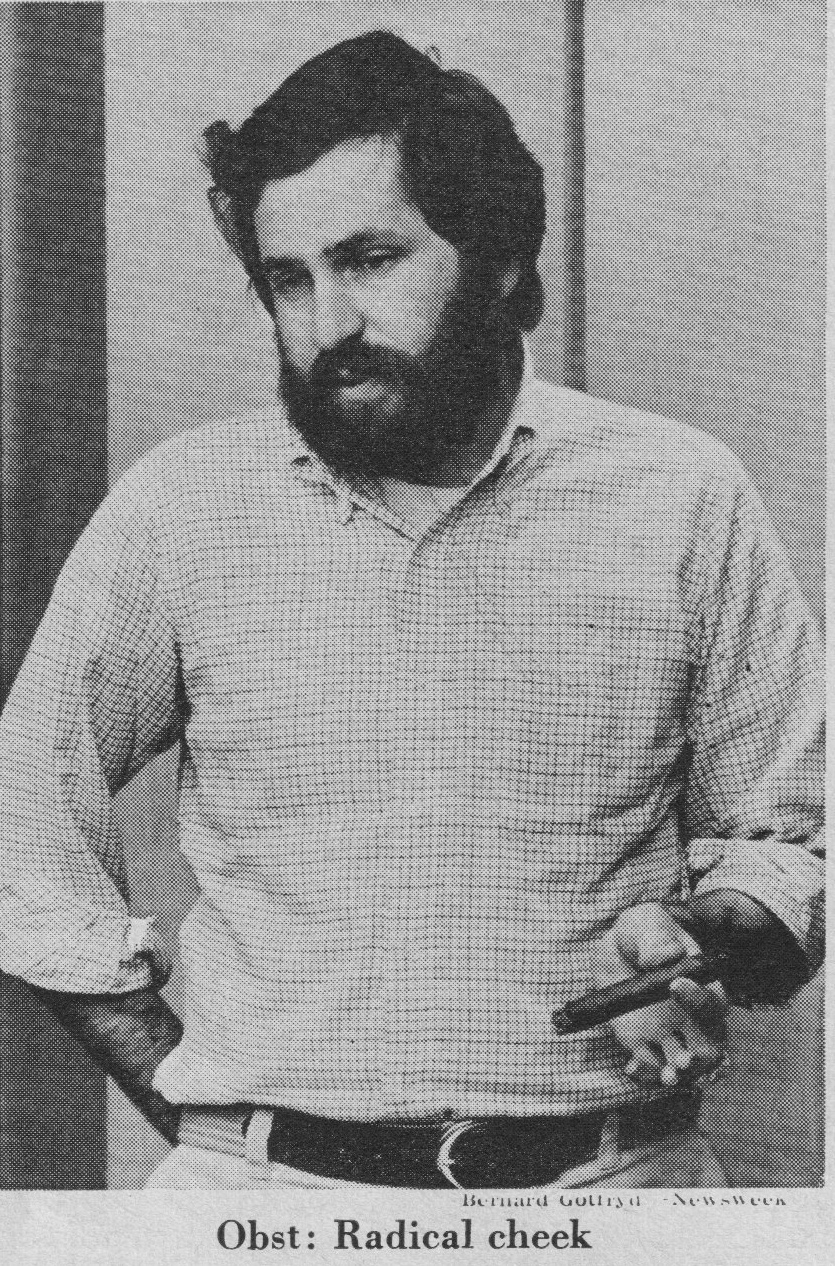

If the nation has a trauma, it’s a good bet that hustling young literary agent David Obst has 10 per cent of it. A 28-year-old walking advertisement for radical cheek, Obst broke into the media by peddling Seymour Hersh’s exclusive My Lai stories when no major newspaper or magazine would touch them, represented Daniel Ellsberg at the time of the Pentagon papers and is literary agent for two of Watergate’s more disparate couples – Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein and John and Maureen Dean.

Obst has turned Watergate into a personal gold mine. In 1972 he was able to coax a $55,000 advance from Simon and Schuster for Woodward and Bernstein’s “All the President’s Men.” The advance for their new book on Richard Nixon’s last 100 days is a whopping $300,000. John Dean’s book, “Decision of Consequence,” won’t be offered to publishers until he gets out of jail, but to tide the family over, Obst has gotten Bantam Books to advance Maureen $125,000 for a love story – hers and John’s.

Other Obst clients range from Watergate burglar Eugenio Martinez to the Senate Watergatge committee’s majority counsel Sam Dash and ex-CIA agent Victor Marchetti. Obst also represents Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle and Uri Geller, the Israeli psychic who bends keys with his bare vibes. Not bad for a kid who surfed his way through high school in Culver City, Calif., and skipped college altogether. “It isn’t easy being a functional illiterate and a literary agent,” says Obst.

After high school Obst spent a few years in Taiwan studying Chinese and, on the strength of a research project he helped with, he talked his way into Berkeley’s graduate school of Asian studies without an undergraduate degree. Obst was radicalized when he was beaten up in the “police riot” at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. Shortly thereafter, he quit school, moved to Washington and set up the Dispatch News Service.

Throught DNS Obst scored his first coup when he finallyh persuaded some newspaper editors that Hersh’s stories breaking the My Lai massacre were legitimate. Hersh was a Washington neighbor of Obst’s. “It was really a high time,” Obst told NEWSWEEK’s Maureen Orth. “We thought if only the America people knew the truth we could end the war. Sy would be flying all around the country trying to find witnesses to the massacre. I would sit on my kitchen floor sixteen hours a day phoning every managing editor in the country.” Meanwhile Hersch would be home at a hot typewriter. “Sy would call and say ‘Touchdown! Start selling’.”

Obst has been selling ever since. After DNS died in late ’71, he briefly toyed with the idea of editing Ramparts, the leftish California magazine, but gave it up. “I thought it was the moment to organize America,” says Obst. “Then I looked over my shoulder and saw no one was following.” No one except the FBI. While setting up a book deal for Ellsberg, Obst flew around the country picking up extra sets of Pentagon papers. “I got to Ellsberg’s footlocker at Bekins Moving and Storage in Los Angeles three hours before the FBI,” he says. “If it weren’t for Watergate I’d probably be in jail now. I was slated to be indicted in a grand jury in Boston as a co-conspirator with Ellsberg.”

‘Eavesdropper’: As events exploded around him, Obst, who prides himself on being a “cultural eavesdropper happiest at the center of the universe,” realized the black clouds of national tragedy had a silver lining in prospective book deals. Obst combed news stories and magazines and called up reporters asking if they were interested in writing books. Then he called publishers and got huge advances. But he knew next to nothing about the mechanics of a book contract. “I’m still learning about negotiating,” Obst admits.

Obst’s unorthodox working habits drive his authors crazy. He disappears for days at a time, to see the comet Kohoutek in Peru or to play backgammon with Hugh Hefner, and he has never answered one piece of correspondence. Woodward and Bernstein threatened to fire him unless he hired a secretary. Obst compromised by hiring an answering service. “I suppose we could have some famous agent,” says Bernstein, “and everything would come in neat little folders, but that’s not the way we operate either. David is our friend.”

Today Obst’s cigars are longer than his hair, and he admits that hobnobbing with publishing fat cats has teneded to deradicalize him. “You get so caught up in the day-to-day activities you don’t notice you’re wearing a three-piece-suit,” he says. Still, Obst gives large chunks of money away and is always ready to help an author whose book he believes in if he can’t get a high enough advance for it. “My consciousness has been altered,” says Obst, adding, “I’ve made a good livng and a good reputation from national tragedies, and I think I’m far from out of business.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments