Original Publication: Newsweek, February 10, 1975

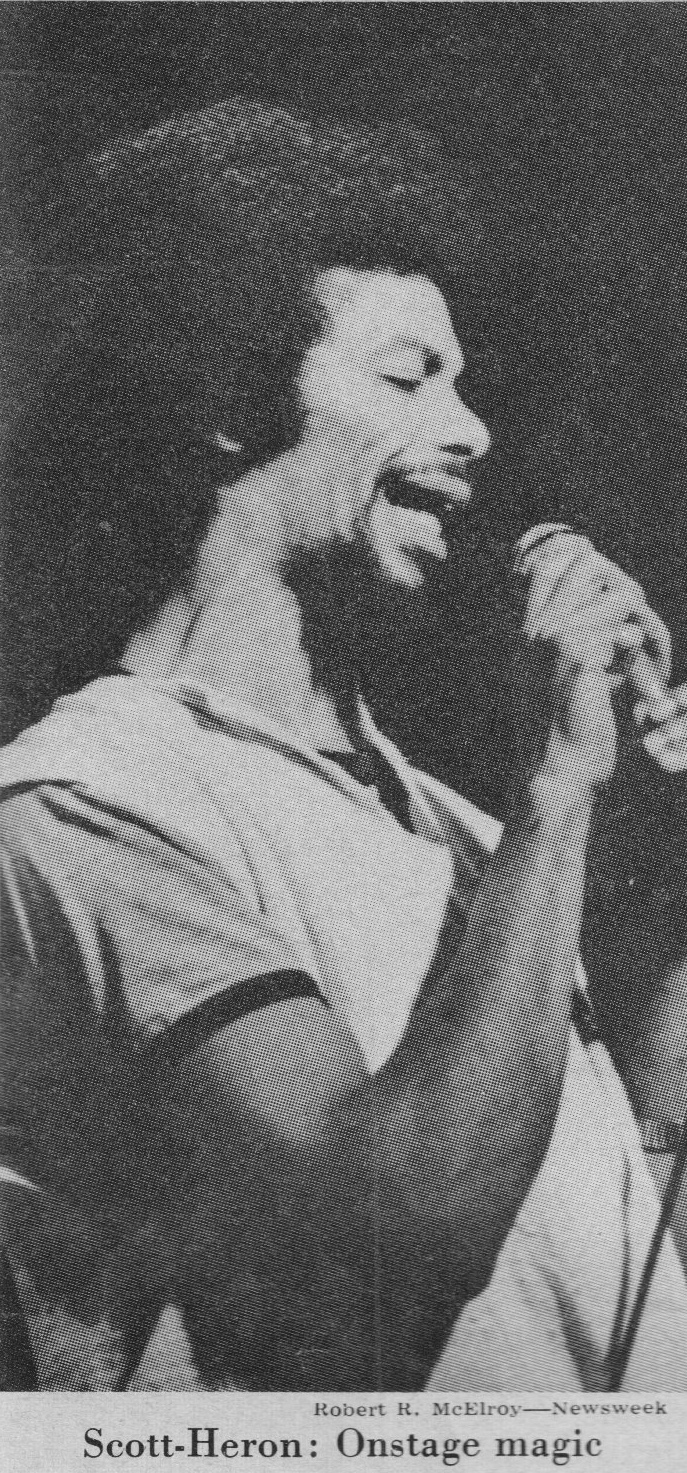

Gil Scott-Heron is a man with a plan. At a time when mindlessness and recycled rockers dominate the hit charts, his Midnight Band’s jazz-based music not only entertains, it enlightens. A poet, novelist and songwriter of the black experience, Scott-Heron, 25, wants to reach a young black audience that doesn’t read much and to continue the African oral tradition by speaking his poetry on records. Though not yet known to a wide national audience, Scott-Heron has both the onstage magic and on-record originality that are the makings of stardom.

In a recent New York nightclub appearance, Scott-Heron was a breathe of fresh commitment. Tall, gaunt, and dashiki-clad, he put down nostalgia as passé and socked it to the superflies by singing, “Ain’t No Such Thing As Superman.” Then he spoke a scathing sequel to his “H2Ogate Blues” – “Pardon Our Analysis,” a poem about the “Oatmeal Man’s” pardoning of “King Richard.” After the performance, Stevie Wonder, who is one of his fans, whispered, “Gil says things a lot of people are afraid to say.”

Evils: Scott-Heron became something of an underground sensation with the release of his last album, “Winter in America,” which he produced with his 21-year-old musical partner, Brian Jackson. Without a nickel’s worth of paid promotion, the album (put out by Strata-East, a small black cooperative label) sold 125,000 copies in the only three cities in which it could be bought – New York, Philadelphia and Washington. One of its songs, “The Bottle,” a danceable discourse on the evils of alcohol in the ghetto, became a national hit on a single, sung by another group, Brother to Brother. Now Scott-Heron has a new major label, Arista, and he is assured national distribution.

His new album, “The First Minute of a New Day,”has a soothing sound and outstanding lyrics that often transcend their raggedy presentation (especially in person, The Midnight Band sometimes sounds like ten guys jamming in the park on Sunday). But a deliberate anti-slickness is part of the plan. Neither Scott-Heron nor composer-pianist Jackson is into the choreographed flash, the love-and-sex sass of much black music. Their songs stress social themes – the need for black unity, brother- and sister- hood. “The black experience is 360 degrees,” says Scott-Heron. “Love and sex are probably two of them, but there are 358 more.”

Scott-Heron’s mother, a librarian, was a magna cum laude college graduate and his Jamaican father was a professional soccer player. But they soon split, and Gil was raised by his feisty grandmother in Jackson, Tenn. She taught him to read when he was 3, and he taught himself the piano by listening to the radio. He wrote detective stories in the fifth grade, inspired by the Agatha Christie novels he devoured around the house. “I missed TV until I was 12,” says Scott-Heron, one of whose best-known songs is “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” “and I still miss it whenever I can. It robs you of your imagination.”

Poets: In the eigth grade Scott-Heron was spat on and cursed when he was one of three blacks to integrate the local school in Jackson. His mother decided to bring him to New York, where they lived in the largely Hispanic Chelsea section. There he absorbed Latin rhythms, adding them to the repertoire of bluesy Memphis sounds he grew up with in Tennessee. Meanwhile, a teacher arranged for him to attend an exclusive private high school. There hs began playing in a band and discovered the black poets of the Harlem Renaissance, including his hero, Langston Hughes.

Folllowing the example of Hughes, Scott-Heron enrolled at Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University, where is was nicknamed “Spiderman” because of his proclivity for slippig through a spiked window at night to practice on the school chapel’s 9-foot grand. After a year he dropped out to write his first novel, “The Vulture,” and a book of poetry, “Small Talk at 125th and Lenox.” When he went back to Lincoln he met a 15 year-old freshman, Brian Jackson, and they began their musical colloboration. Scott-Heron earned a master’s degree in creative writing at John Hopkins University while writing another book, “The Nigger Factory.” Today he teachers creative writing at Washington’s Federal City College and lives communally with three other members of the Midnight Band in nearby Arlington, Va. Often topics of discusssion around the house end up as songs.

“I worry about the lack of movement among blacks,” says Scott-Heron. “We were active for fifteen years but we lost a lot of warriors, and sometimes you need to regroup. I think anyone who is capable has a responsibility to maintain the awareness. We need to turn to each other instead of to the government or white folks. We have enough talent, knowledge and ingenuity in our own community. If we were ever to find that magic plateau called unity, we could be free.” In these unpolitical days, Scott-Heron is using his music to search for that plateau.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.