Original Publication: Newsweek, October 24, 1975.

Suddenly a mirror shattered. “Maureen, bring me a virgin!” shouted Lina. After five weeks in Italy working as an assistant to Lina Wertmuller, I thought the request utterly normal. When a mirror breaks, according to an old superstition, a virgin must urinate over it within 24 hours. Then, to wash away the evil spirits, it must be thrown into the Tiber. “I’ll get one of those teen-agers in wardrobe,” I replied. “Absolutely not,” said Lina. “In this day and age I trust no one over the age of 8. Bring me an 8-year-old virgin.” We finally settled on a 4-year-old whose parents wanted to be extras. That night I put the mirror in a plastic bag and dumped it in the Tiber.

Working with Lina Wertmuller, you never know whether you’re learning about making movies or testing your threshold of survival. When Lina and I met several months earlier in New York, she invited me to work as a production assistant on “Seven Beauties.” I accepted and suddenly found myself on a feverish eleven-week merry-go-round. We traveled from a Neapolitan insane asylum to a bombed-out factory near Rome that Lina transformed into the film’s Nazi concentration camp. My friends were dwarfs, giants and Lina’s other two female assistants – voluptuous Alessandra, who lived with a deaf clown, and Lucy, a young radical from California. When Lucy resisted being cast as a topless Nubian slave in a warehouse scene, Lina scoffed: “Cinema is all tricks and fantasy. If you don’t want to participate in the fantasy, go back to the university.”

Snores: Wertmuller likes to use non-professional actors, the more grotesque the better, and she sent me through the back streets of Naples to search for “interesting faces.” I discovered a lot of Neapolitans have goiters. “Scusi, ” I said to one fat man seated at his door, “le interessa fare un film?” “Si, ” he replied and he became Totonno the pimp, one of the male leads. He never saw the script, but then Lina wasn’t interested in his understanding of the character – she wanted him for his face. Her forte is spontaneous invention, and one day during his post-lunch snooze she hushed the set and recorded his snores. “I have no idea what this film means yet,” she had confided to me. “I will only know in the editing room.” Later the snores became a key element in the scene in which he is murdered by the film’s hero.

Before making her first film, “The Lizards,” in 1963, Lina spent years writing and directing plays, and her life and personality are infused with theater – the theater of paradox. “I dedicate my films to the masses,” she told me one day in her throaty voice, twirling the chunky necklaces she always wears. “They must hurry up and understand the problems of the world or the world will come to an end.” A few days later she allowed the “masses” – a hundred extras – to sizzle for hours in the hot Mediterranean sun without so much as a water break. “Remember, girls,” she liked to say, “Napoleon lost Waterloo through lack of communication.” But on the set, her main means of communication was to scream creative curses.

Lina also “acted” out all the characters herself, crouching under the camera lens, feeding – or changing – dialogue and expressions during takes. (In Italian movies all of the real sound is dubbed in later.) She had the actors – even in love scenes – a lay their closeups to her face. Incredibly agile, she thought nothing of hanging from a rooftop to get a camera angle she wanted. Once, she stopped me from translating a point to Shirley Stoler, the American actress who plays the Nazi commandant, saying, “I don’t care if she understands what I say, I just want her to imitate what I do.” When her renowned director of photography, Tonino Delli Colli, complained that her insistence one subdued interior lighting would make other cinematographers think he no longer knew how to light a scene, tiny Lina (she’s just over 5 feet) would plop down on even tinier Tonino’s lap, put her arms around him and murmur, “Amore, trust me.” He never did.

Adoration: But she became a genuine kitten whenever her husband, Enrico Job, appeared. With Enrico, a sculptor, conceptual artist and the production designer of her films, Lina was almost childlike in her adoration. She also adores Giancarlo Giannini, the only other person to whom she never raised her voice. Giannini’s Pasqualino was based on a real person, an Italian-Jewish survivor of a concentration camp who had murdered his sister’s pimp – and who was cast as a prisoner in the film. But while everyone else was straining to recreate his life, the real Pasqualino sat around every day virtually unnoticed – a gnarled, hook-nosed extra.

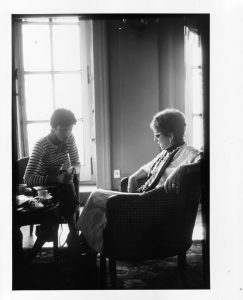

In the course of the filming, my mother visited me and, to everyone’s astonishment, Lina cast her as the madam of a bordello and me as a whore. Our eyebrows were shaved and we both got red Betty Boop mouths. For three days, we were pulled, powdered and pampered. My god, I thought, this is how Cher must feel every day. Lina told me that I moved my face in “too American” a way. “Try to look mysterious,” she said. When it came time to do close-ups, Lina jumped around like a cheerleader. “Look this way, breathe, now this way. Brava!” she said, and blew me a kiss. Later, Raffaele, the prop man, told me, “I like working for Lina because she’s crazy and has the strength of a hundred men. She’s the kind of person who, while she’s beating you to death, makes you believe it is really you who are killing her,” D’accordo.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.