Original Publication: Newsweek, December 15, 1975.

Paul Simon should be on top of the world. His latest album, “Still Crazy After All These Years,” was No. 1 on the Billboard hits chart last week. His single, “My Little Town,” sung with ex-partner Art Garfunkel, was no. 10. In October he won high ratings as host of an NBC “Saturday Night” show. Last week he wound up a sold-out national tour with four performances at Avery Fisher Hall in New York City – and immediately began preparing for six concerts in Europe and a television special to be aired New Year’s Eve on the BBC.

But Simon, the cerebral and careful craftsman of some of pop’s most memorable melodies – “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Mrs. Robinson,” “The Sound of Silence” – is not exactly feelin’ groovy. “Pop music is in a terrible state right now,” he says. “It stinks. Only a handful of people are doing something good.” One of the handful is Bob Dylan, to whom Simon has recently been compared in the press – unfavorably. “Dylan comparisons make me emotional,” says Simon.

“There’s hardly a point of comparison except that we’re the same age. (Both are 34.) He writes a lot of words. I write few words. In the 1960s Dylan for the first time used the folk tradition of Woody Guthrie and sang a grown-up lyric. He singlehandedly took the folkie emphasis on words and made it the predominate style of music in the ’70s. But what he has spawned is boring.”

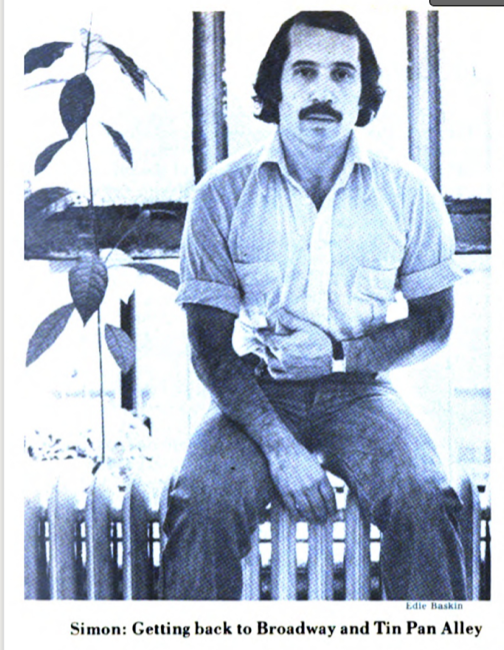

Pensive and soft-voiced, Simon gazes out his picture window overlooking New York’s Central Park. “When I listen to Dylan I think, ‘Oh no, not the same three of four chord melody again.’ Then I look on the back, read the lyrics and know he’s valid. But the staple of American popular music is all three or four chord, country or rock oriented now. There’s nothing that goes back to the richest, most original form of American popular music – Broadway and Tin Pan Alley – in which sophisticated lyrics are matched by sophisticated melodies.”

Space: Simon wants to extend that tradition. “When I started writing I didn’t think there was any space for me between Dylan and the Beatles – they had it covered. I was writing little psychological tunes based on wandering melodies. Now I’m trying to get closer to Broadway and Tin Pan Alley.”

In fact, rock’s most influential figures have roots in other traditions. Stevie Wonder knows what Duke Ellington composed and Charlie Parker played. Dylan has Guthrie and also Allen Ginsberg and the other beat poets. Paul McCartney filters American rock ‘n’ roll through the British music-hall tradition and European folk ballads. “It’s no fluke,” says Simon, “that me, Berlin, Gershwin, and Kern are all Jewish guys from New York who look alike.”

Simon, who usually takes three months to write a song, studied formal music theory and harmony for a year and a half. On his records he draws from a variety of musical forms – from Jamaican reggae and black gospel to Peruvian music and the gypsy guitar of Stephane Grappelli. He admits that his lyrics, as critics have charged, may sound cryptic and dispassionate. But he insists that they are deeply felt. “In my last album I wrote a line, ‘Love emerges and it disappears’,” says Simon, who was divorced this year. “Now that’s a big emotional coming and going. I’m aware of that, but I’m not attempting to analyze or sum it up, because I don’t understand it. Writing songs is cathartic. It’s a way of saying what I don’t say to people.”

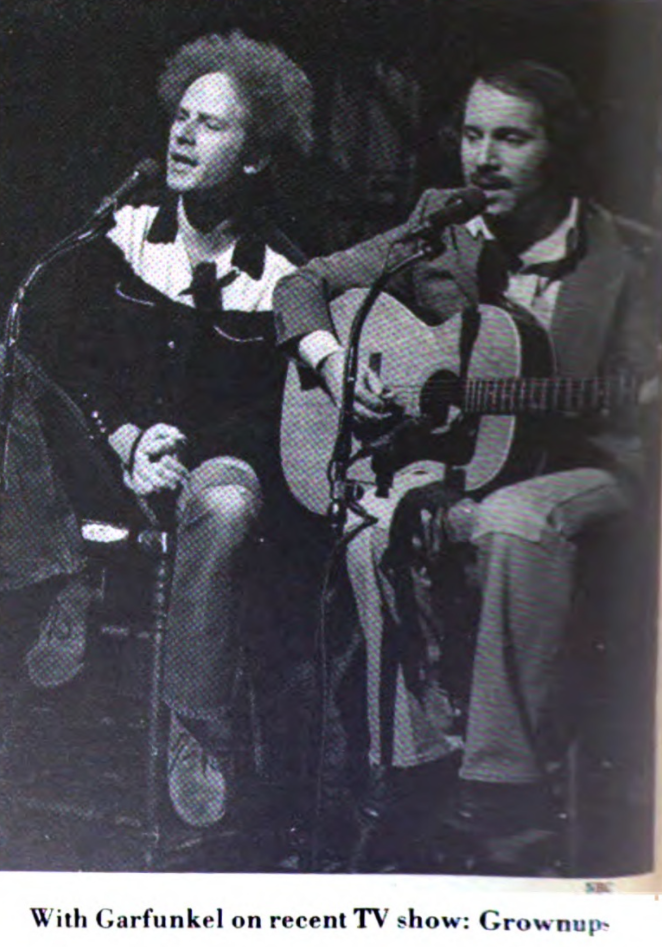

Prison: The most effective song on his “Still Crazy” album is “My Little Town,” sung with Garfunkel. In the five years since their partnership broke up, Simon has resumed a different friendship with Garfunkel, but he is adamant that he will stay on his own. “I can’t go back to doing anything with Artie,” he says. “That’s a prison. I’m not meant to be a partner. Besides, I don’t know if Simon and Garfunkel would be that popular if they did come back. Artie came out onstage with me three times on this tour and the reaction was intense and astounding. But if we’d done a 40-minute set, there wouldn’t have been that reaction.

“Poor Artie,” added Simon. “He’s really depressed now. (The critics drubbed Garfunkel’s current solo album, “Breakaway.”) If only Artie would sing as intelligent as he is. That’s why I wrote him ‘My Little Town’ – to write a nasty song about someone who hated the town he grew up in. Artie’s not all romance. He’s got brains, bitterness, pain and scars. He just happens to have a voice like an angel and curly hair like a halo. But he’s a grownup.”

Simon’s next album will not be ten random pop songs, he says. Instead, it might contain the score of a new Broadway musical or a movie based on his own family roots. All three networks would like to grab him for a special, and he’s also interested in doing music for an animated children’s-television show. And he’s determined about one thing: no more national tours (“They take up too much time”). “I’m entirely antagonistic to the mainstream,” says Simon in waving goodbye to the conventional pop star’s career. After all these years, that’s not so crazy.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.