Original PublicationNewsweek February 9, 1976

Everyone in Hollywood will tell you that Tatum is worth every penny of that extraordinary deal. From Jackie Coogan, who started it all in 1921 in Charlie Chaplin’s “The Kid,” to Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, Margaret O’Brien and the young Elizabeth Taylor, the child star has been a lucrative–if recently rare–commodity. Tatum O’Neal, Hollywood is convinced, has as much “wanna-see” appeal (as the current jargon puts it) as Temple and Garland every had. In “The Bad News Bears” she plays a Little League pitcher on an otherwise all-boy team. This week she begins filming “Nickelodeon,” in which she stars as a movie groupie, circa 1910, who ends up writing scripts and driving a Stutz Bearcat. Mengers claims to receive at least three scripts a month tailor-written to Tatum’s personality. What everyone has in mind is another “Paper Moon.”

A brown Porsche pulled up to the Beverly Hills Hotel at lunchtime one day last year, and out stepped Tatum O’Neal in white gloves and a hat. She marched straight into the Polo Lounge, met her agent, Sue Mengers, ordered Perrier water and got down to business. “Sue,” said Tatum, then 11, “I don’t feel very comfortable with children my own age now, and I’d like to work again.” “It’s just a stage you’re going through,” replied Mengers. “I know it,” said Tatum, “but while I’m going through it I’d like to work.” Mengers got the message. A few months later Paramount Pictures signed Tatum to star with Walter Matthau in the soon-to-be-released “The Bad News Bears” for a fee of $350,000 plus 9 percent of the net profits, making her the highest-paid child in the history of movies.

For “Paper Moon,” her first and only released movie to date, Tatum got paid $16,000 and Paramount grossed more than $45 million. Her part was straight from the Hollywood of the 1930s: an orphan in search of a father during the Depression. But her take was strictly 1970s: as Addie Loggins, the 9-year-old cigarette-smoking con artist, she was as precocious as Shirley Temple without the lollipop sweetness, as game as Judy Garland without the wide-eyed anxiousness to please. Hip to adult hypocrisy, tough but vulnerable, she walked off with the movie and later an Academy Award, and her triumph was all the more appealing because her co-star and father figure in the movie was her own real-life father, Ryan O’Neal.

Almost as soon as “Paper Moon” opened, however, Tatum “retired” from the movies–at her father’s insistence. He explained that he wanted her to have a “normal” childhood: it was rumored that Tatum had developed ulcers from all the interviews with the press. But she hardly retired from the public eye. She was photographed by Irving Penn for Vogue magazine dressed up as Charlie Chaplin and as Raquel Welch—wearing balloons in her bust. She appeared on a Cher show, playing a 12-year-old wife suing for divorce, imitating Cher in full-length sequins and platform shoes and spoofing a Catherine Deneuve perfume commercial with her own French-accented pitch for Bubble-Loo Bubble Bath.

In London, she went on well-publicized shopping sprees with Bianca Jagger. Andy Warhol interviewed her. She vacationed in Hawaii with Cher. And she and her father emerged as Hollywood’s oddest in couple, bumping in discos, tablehopping in nightclubs—Tatum wearing jewels and necklines slashed to there. To her pre-pubescent contemporaries, Tatum’s life looked as if it dripped with grown-up glamour. But the reality of being a Hollywood kid was—and is—less enviable.

Last month, police burst into the old John Barrymore house in Beverly Hills, where Tatum lives with her father, and arrested Ryan O’Neal for possession of 5 ounces of marijuana. The arrest was prompted by an irate parent who had discovered that his 10-year-old son had been given marijuana at the O’Neal house by a 28-year-old maid. For Tatum this was only the latest chapter in a childhood that reads like a cross between Nathanael West and Jacqueline Susann.

Do I think other girls my age envy me or wish they were like me? It’s like watching the Osmonds walk by. Everyone must think, Oh look at the Osmonds! What a great life they have. It must be so much fun. Well, look at all the troubles I have.

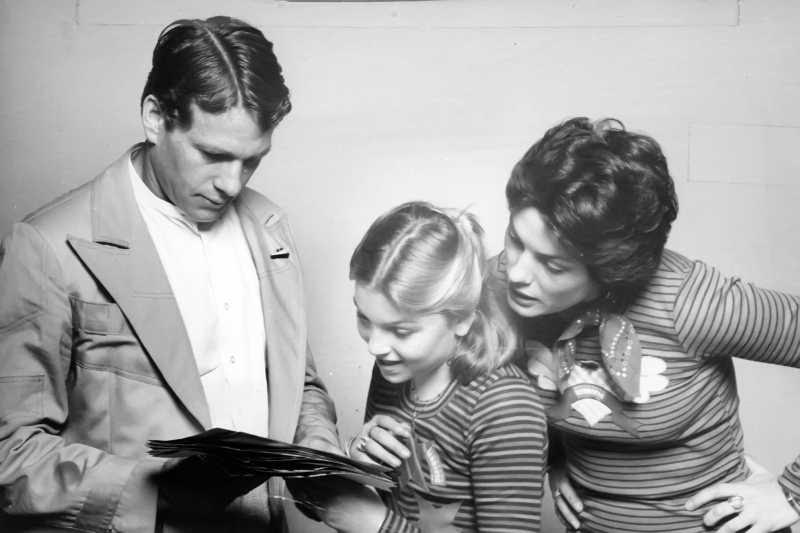

Ryan O’Neal was 21 and an aspiring TV actor when he met Tatum’s mother, Joanna Moore, who was almost ten years older than he and a more established performer. “She was pregnant within days of our meeting,” he says, “and we were married within weeks.” Ryan was the son of a Hollywood scriptwriter of modest success, Charles (Blackie) O’Neal, and his glamorous wife, Pat, an actress who gave up her career to raise her family. The family has always been extremely close-knit. “Ryan wanted the same kind of family for himself,” says his mother, “but he happened to choose strange wives.”

When Tatum was born, Ryan took to fatherhood instinctively. “I was the nanny,” he says. “Joanna was working and for the first ten months of Tatum’s life I trained her. She could stand up balanced in the palm of my hand at four months. One day I threw her off the roof of the house into the deepest part of the pool. I dived in and brought her up standing in my hand and she was laughing.”

One year later a son, Griffin, was born and Ryan’s career began to blossom when he landed a leading boy-next-door role in the TV series “Peyton Place.” But his marriage had become, by his description, “desolate.” When Tatum was 2, her parents separated and a year later were divorced, with Joanna retaining custody of the children. Ryan, who had been linked romantically with nearly all of his leading ladies on “Peyton Place,” married one of his co-stars, Leigh Taylor-Young, who was pregnant. Joanna took the kids to live on a small ranch in the north end of the San Fernando Valley.

“At first,” says Joanna Moore, “I thought the ranch would be a beautiful existence, but it turned into a nightmare.” For years Joanna had taken diet pills to stay thin, and that habit had turned into a serious dependence on methedrine. “I used to take a little pill to help me through,” she says, “and before I knew it, I had taken enough to eventually undermine me. I was strung out.” “They were living in this shack with a dying horse and some dead chickens,” says Ryan, “and I was paying her $30,000 a year in alimony. Tatum was growing flowers in a wrecked car in the front yard and cooking breakfast and lunch for herself and Griffin.”

Ryan’s parents pitched in to try to bring some order to the chaos. “There were such emergencies for so many years,” says Pat O’Neal, “it nearly killed us. The experience would have destroyed some children, but they were so used to being left with strangers in the neighborhood or in a bar that they made fantastic adjustments.”

When Tatum was 8, Joanna went to Ryan to ask for help. She wanted to be cured of her addiction. Ryan wanted something too—custody of the children as the price of his support. Joanna entered a hospital. Within months she was cured—and has stayed cured—and in due course they compromised on custody. “Griffin wanted to stay with me,” says Joanna, “and Tatum wanted to stay with Ryan. She really hated me then. One of the first things Tatum did when she saw me after the hospital was spit in my face. It was the most painful experience of my life—like having a child die. It was the most undisguised, outrageous hate I have ever known.”

I have a bunch of favorite child stars. Margaret O’Brien is one. Shirley Temple? She wasn’t very good. She was only good when she was 6 or 7. Did you ever notice she couldn’t act when she was 14? She sure was pretty, though.

For Tatum, child stardom came just in time. Anything but a model student, she had been expelled from a private school for stealing and fist-fighting when she was offered the chance to act in “Paper Moon.” “It was a school for rich kids with neurotic problems,” says Ryan, “and the movie answered the question of what to do with this strange little girl I was living with.” (He and Leigh Taylor-Young were divorced in 1974.)

It was Polly Platt, “Paper Moon’s” production designer and the ex-wife of director Peter Bogdanovich, who “discovered” Tatum. “Tatum had come to visit Ryan on the set of ‘The Thief Who Came to Dinner,’ and I noticed her raspy voice,” says Platt. “I could also see she was very advanced.” Some months later Bogdanovich called Platt to say he had been offered a script that had originally been intended for Paul Newman and his daughter, but he couldn’t think of any reason to do it. Platt read the script and called right back. “It’s brilliant,” she told him, “and I know who should play the little girl.” That weekend she took Bogdanovich to Ryan’s beach house in Malibu to meet Tatum, who was supposed to know nothing about the visit. As soon as Tatum met him she turned to her father and said, “Is this the guy who’s going to direct the movie?” Then she looked Bogdanovich up and down and said, “You don’t have a very good body.” Bogdanovich was charmed—more or less—and Tatum, at 8, got the part.

Tatum was a natural onscreen—but not without a great deal of help. During “Paper Moon’s” grueling twelve weeks of filming in Kansas, Bogdanovich coached her heavily—to the point of bribery (what started out as 50 cents for getting her lines right gradually reached $50). “Even so,” says Bogdanovich, “I never coddled her.” Now as he prepares to reunite Tatum with her father as co-star (along with Burt Reynolds) in “Nickelodeon,” Bogdanovich admits to “feeling guilty sometimes” about the impact of “Paper Moon” on Tatum. “I feel a little bad she’s not getting the childhood some people wish she’d have,” he says. “We put Tatum in ‘Paper Moon’ without thinking deeply about the consequences. But it’s too late now to think about them.” “’Look what we’ve done to Tatum’ is such a boring cliché,” says Platt. “Would you prefer she just stay in that big house with Ryan and watch the parade of freaks coming through?”

At 9 I was a little brat. I had not grown up at all. At 10 I started growing up a little bit but not really. At the end of 11 I was pretty good and now—at 12—I’ve grown up but it hasn’t blossomed yet. Now I’m just a bud. At 40 my blossoms will be open. At 70 they’ll be bending back and then I’ll die. It’s a pretty good way of looking at it, don’t you think?

Although Ryan insisted that she not accept any more acting offers, movies dominated her life after “Paper Moon.” She lived with him in London while he was filming “Barry Lyndon” for Stanley Kubrick and was tutored with the Kubrick children. When she got back home, she found going to school difficult. She seemed indifferent to her studies. “I had to do her homework just like I used to have to do Ryan’s,” recalls Pat O’Neal. And she did not get along well with her schoolmates. “One day,” says Ryan, “she came home and told me that when she told the children in her class she wasn’t coming back the next year, they applauded.”

In and out of various schools, Tatum was finally given a private tutor. At one point she announced that she wanted to use her “Paper Moon” earnings to buy a horse ranch. “You only made $16,000,” said Ryan. “That won’t buy it.” In that case, said Tatum, “I’d like to go back to work. How much could I get?” Ryan said that he’d talk with Sue Mengers.

I don’t play dummies.

“What’s so good about Tatum onscreen,” says Bogdanovich, “is that she’s got a certain toughness—a maturity beyond her years. It’s always amusing if a child behaves older than she is by about 30 years.” In Hollywood today, Tatum is one of the few actresses who consistently get offered intelligent roles, and she is well aware of her special status. She fired three chauffeurs from the set of “The Bad News Bears” and last fall, in the great Hollywood tradition, clashed with her co-star, Walter Matthau, although they ended up friends. “In Tatum’s case,” says Matthau, “people treat her like a spoiled child star and they get the same treatment back. I found her to be cooperative and interesting. She knew what was happening, say, in China. She knew the news. She was intelligent, bright, well-mannered. And she knew that acting was a team game. She’s serious, yet she has fun.” “Inside a 29-year-old 11-year-old,” says “Bears” director Michael Ritchie, “there is a 12-year-old struggling to get out.”

To the press I’m “Taticums” or precocious. They hate me because I’m at parties and act like a grown-up. But if you’ve been to one Beverly Hills party, you’ve been to them all. I don’t consider myself a child or a grown-up. I don’t try to do a lot of the grown-up things that are intimate. I don’t have sex yet. I don’t take drugs. Just because I go to parties or dress or act like an adult it’s not that I’m so grown-up. I act poised. I’m not rambunctious. After all, I’m 13—I mean 12.

“Underneath, Tatum is a sensitive, kind little girl,” says Polly Platt. “She desperately needs a mother.” Today, Tatum sometimes seems like a mother herself—especially to her own parents. She now sees her mother regularly, and when the family sat down to discuss the drug bust Tatum was “the mediator,” says Ryan. “I let her do all the talking to Joanna. I just sat back and ate walnuts.”

Although he now encourages the rapprochement between Tatum and her mother, Ryan at first felt threatened by it. “One day Tatum and I were playing pool and she was beating me,” he recalls. “Joanna phoned to say she’d seen ‘Paper Moon,’ that she liked me in it but thought Tatum was too cold. Tatum got on the other line and said, ‘But, Mother, I was playing a part.’ Those were the first words they’d spoken to each other in a year. They talked for 45 minutes and I thought, ‘My God, I’m going to lose her.’ I felt like a dying lover. I thought, ‘I’ve fallen in love with this little girl’.” The call was a false alarm. Tatum’s heart still belongs to Daddy.

I think independent relationships are great. But women are so free nowadays. I notice how they come on to my father and flirt. Some women—if the man says, ‘I’m going to the bathroom,’ the woman says, ‘Oh, can I come too?’ It’s gross. There aren’t many women in Beverly Hills who are interesting. There’s nothing real or down-to-earth about them.

Ryan bought his and Tatum’s current house with the furnishings of its previous owner intact. Tatum has her own bathroom with a picture window next to the tub overlooking Beverly Hills. Her brown-and-white canopied bedroom—with her Louis Vuitton luggage neatly stacked in one corner—is just a few steps away from Ryan’s red-canopied one. Tatum makes no secret of the fact that she barely tolerates the beautiful women she often finds across the hall. And when they go out with Daddy, she goes too.

Tatum fights with Ryan’s dates over who gets to sit in the front seat of their big gray Mercedes, but more often than not she is his only date. “I take Tatum to parties,” says Ryan, “because I decided I would raise my child, and I found she wouldn’t let me go anywhere without her. Tatum has a very strong jealousy syndrome. I set that up, though. It was an accident, but I did it because we were inseparable.”

My relationship with my dad is extremely precious. Nobody in the world has a relationship like that. Me and my dad—it has nothing to do with sex. It’s not perverse. Some people think like that because we’re too close. People are weird. My mother? Just say Tatum’s mother is a very good actress. Go see her in “The Hindenburg.” She should be getting more job offers.

Her father has a bizarre theory that Tatum’s energy was infused before birth. “It’s her mother’s speed in her,” he says. “That chemical goes into the fetus. Tatum can go all night without sleep. She clicks into another gear. What do you think makes her such a beautiful actress?”

While waiting for her shooting to begin, she visited the “Nickelodeon” set to watch her father play a scene. After a take, he would look over at her for approval. While Bogdanovich was giving instructions, she put her arms around him, then made horns with her fingers and held them behind his head. Bogdanovich said softly, “If you don’t be quiet, Tatum, I’m going to get very angry.”

Later, in her father’s dressing room, her mood ring had turned black. “Peter had no right to yell at me like that,” she said. “It was so insensitive. I may quit this picture.” She opened her make-up case to prepare herself for a photo session, explaining, “I like a European look,” then requested to be left alone while she did her face. “Please, I just need a minute.”

Tatum claims to have “come totally off that real glamour-girl thing.” But when she walked into the wardrobe room, she spied a red snakeskin pantsuit and shrieked: “Jesus Christ, I’m in love! I have to have that.” Next she spotted the elaborate Cecil Beaton hats left over from “My Fair Lady.” She made a series of grand entrances with them, announcing, “Ooh, ladies, I feel flush,” and “Saks Fifth Avenue, fifth floor please.” When a wardrobe woman told her to pick up a pair of overalls she had just tried on and left on the floor, she obeyed. When the wardrobe woman turned her back, she stuck out her tongue.

Nine and 10 were my hard times growing up. Now I think it’ll be easy. It’ll probably last this way until I’m 15 or 16. Then boys will be a heavy thing in my life, I guess. But I don’t have a worry in the world right now. I’m all organized. I’ve got my whole act together. I just need a couple more pairs of pants.

Now that she’s 12, 5 feet tall and losing her baby fat, Tatum won’t be a child star much longer. She sometimes says she’d rather be in school with her friends than act. But no matter what happens, Tatum O’Neal will be a survivor. “Tatum is into self-preservation,” says her grandmother. “The world could wither up and die but she’ll find her way through anything.”

Late one recent evening, Ryan bribed Tatum into going for a ride with him by promising that she could drive home. Tatum climbed into the back seat of the Mercedes, and as he swung behind the wheel Ryan sighed, opened his blue eyes very wide and remarked: “Basically it’s just Tatum and me. We try to keep everything very simple.” From the back seat came a loud “Harrrrumph. Daddy, who do you think you’re kidding?” Tatum O’Neal does not play dummies.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.