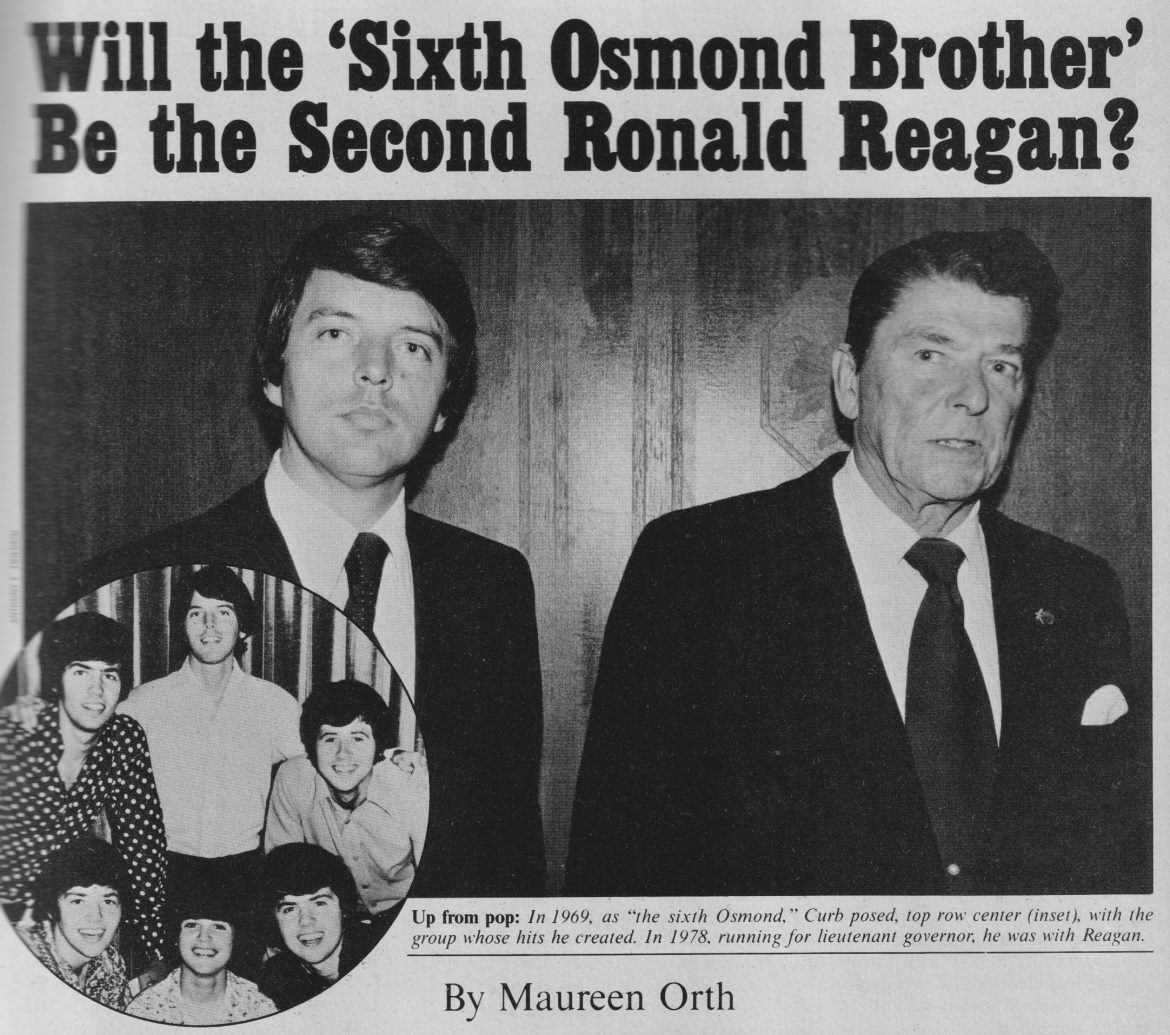

Original publication: New West, March 27, 1978

Mike Curb looks and moves like a grown-up Ken doll and, characteristically, when he doesn’t think you’re looking, he frequently sprays Binaca breath freshener into his mouth. He was just about to take a squirt during Warner Bros. Records’ post-Grammys party at Chasen’s when, abruptly, Jerry Weintraub, John Denver’s manager approached. Weintraub wanted to introduce Mike Curb to John Denver, a meeting that would be auspicious because Denver, it should be understood, has confided to friends that he has presidential aspirations, and so does Mike Curb. “Mike,” said Denver, “I hear you’re a candidate. That’s wonderful. I wish I were a candidate.” But John Denver has to wait. He hasn’t had any hits on the charts lately, and Mike Curb has.

Mike Curb, the man who brought “You Light Up My Life” to Debby Boone and who formerly produced Donny and Marie, is Ronald Reagan’s hand-picked candidate for lieutenant governor of California. A self-made millionaire, virtually unknown to the public, Curb, at 33, is suddenly being touted in the press as the squeaky-clean Young Man Most Likely to Succeed in the GOP. People who work with him also know him to be, in the business arena, “a baby-faced killer.”

Curb is president of Warner/Curb Records, and responsible for creating nearly $20 million worth of record sales for the once-hippest recod label, mostly by having golden oldies re-recorded by born-again plastics. On Grammys night, Curb’s clean-living angels dominated Chasen’s, a scene that would have been unimaginable at a Warners’ party three years ago. In one corner was Curb artist Debby Boone, flanked by her proud papa, Pat Boone. In another corner, another Curb product, tiny teen idol Shaun Cassidy, greeted his mother – Pat Boone’s old screen heartthrob, Shirley Jones. In the middle of the room sat Curb’s mother, father, sister, brother-in-law and fiancée, Linda Dunphy.

No wonder freewheeling Rod Stewart was leaning against the bar, scowling, his open-to-the-navel white ensemble a clashing contrast to Mike Curb’s neat, blue pinstriped suit. No wonder Fleetwood Mac had already retreated enmasse to the back room and Steve Martin chose to keep his eyes parallel to his plate. Most uncomfortable of all was Warner Records’ chief, Mo Ostin, an old-line liberal with an eye for the unorthodox. “You know,” Ostin reminded, “I signed Jimi Hendrix. I signed the Fugs and Frank Zappa and Tiny Tim.”

“And how do you explain all this?” he was asked.

“Just let me finish my dinner,” he answered.

Pat Boone, a Republican, was more relaxed. “I was asked to run for Congress ten years ago,” he said, “but I felt I was not qualified, so I said no.” Boone has appeared frequently at Republican fund raisers, many times at the request of Mike Curb. He is now on Mike Curb’s executive steering committee. Nevertheless, Pat Boone said, “In Mike’s case I’ve really voiced my serious concern if he should become lieutenant governor because as a record executive he’s helped shape the industry and the thinking of young people. Personally I wish he’d stick to the record business.”

Mike Curb is being trotted out as the man who can unite the GOP and appeal to the crucial 18- to 34-year-old vote. He is being pushed forward by the same right-wing elder fat cats who launched Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan – men like Holmes Tuttle, Justin Dart and Henry Salvatori. Because of Curb’s role as Ronald Reagan’s presidental campaign chairman for California in 1976, and then as co-chairman of Gerald Ford’s winning effort in California during the last election, he is perceived not only as a new young face, but also as a proven winner who has the grass-roots conservatives on his side. What’s most newsworthy about Mike Curb, however, is that he’s the first candidate from either party who has built a power base by providing entertainment for political functions. Reagan capitalized on show-business fame, on name recognition, to launch a political career. But with the recent strictures on campaign financing, Curb is pioneering a way of cashing in on show business as political power.

The tough campaign-spending law of 1976 contains a loophole that allows entertainers to donate proceeds of their performances to political candidates, thus making show business one of the last remaining sources of big-money contributions. For the last few years, show-business figures who can deliver big-name acts have become increasingly influential behind the scenes in political campaigns. Mike Curb is unique among them because he has decided to step personally into the limelight. Curb has no previous elective experience, but he’s been the Republicans’ man in pop music – a position few coveted.

All those nights in which he schlepped the Mike Curb Congregation – his group of blown-dry, vinyl-booted singers created in his own image – to sing “God Bless America” at Republican fund raisers, are now paying off. Curb is collecting IOUs in the GOP; he was able to almost instantly “persuade” all but one opponent, State Assemblyman Mike Antonovich, not to run against him. And his rise to prominence in the Republican Party is attracting the attention, and the money, of the rich music industry. Last December, at a “Friends of Mike Curb” fund raiser, the largely industry crowd put up a cool $225,000 at $250 a plate to launch Curb’s campaign. The support was particularly thrilling to Mike Curb, because seven years ago he was one of the most hated and villified figures in his industry. Back then, as the 25-year-old president of MGM Records, he had denounced the use of drugs by rock bands, even linking drug use to rise in veneral disease, which prompted the Hollywood Reporter headline: CURB THE CLAP. He pledged to drop any MGM acts who admitted using drugs. Many in the industry, who knew he was already trimming acts, deplored the expedience of his stance as well as the philosophy.

Since that turbulent time, Mike Curb has come back in a big way. He has had four number-one records by four different artists on the hit charts in the last eighteen months. In the recording industry, that kind of uncanny ability commands respect. As a result, many people at his fund raiser were wiling to turn their backs on the usually liberal political beliefs in order to launch a pro-death penalty, antiabortion candidate. “I was flabbergasted at who showed up,” says Holmes Tuttle. “There were staunch Brown supporters there!”

What was partly at work at the fundraiser was old political cronyism in a new setting, that familiar rite of politics known as “supporting one’s own.” As members of a nouveau riche industry, record people are eager for certification of their clout. Moreover, according to Curb, “The entertainment industry is beginning to realize that its vested interests cannot be dealt with unless it gets more involved. It can no longer stay on the outside and be looked upon as a bunch of drug and payola people. By vested interests, I mean an image, a proper image for the industry.”

It is not surprising that Mike Curb would consider image to be a vested interest. He deals in image, and the image he projects is that of a new, bionic Ronald Reagan, a politician whose appeal will not depend as much on detailed ideology as Reagan’s does, but on a set of symbols that say, “I’m hard-working, rich and attractive. I believe in our system and, if we package it properly, it can work.” Through his public appearances, Curb wants to be perceived as a self-made millionaire workaholic, a nonpolitician, a man who’s never failed. However, he’s not yet mastered public speaking, he has no advance men, and he arrives everywhere late, with no real sense of the demands of a campaign.

Reagan, for one, does not regard any of this as a major handicap. The ex-governor was laughing recently as he said, “How could it bother me that Mike Curb has no previous political experience? I never served in political office when I started. The founding Fathers weren’t politicians.” Curb and Reagan were supposed to be paired on the dais at a San Gabriel Valley Explorer Scouts benefit luncheon in Pasadena. But as usual, Curb had not shown up. Reagan, who had arrived on the dot, wasn’t fazed. “Mike is an extremeley successful young man for his age,” said Reagan. “You’re always on the lookout for new, younger leaders in the party.”

Was the governor particulary fond of Mike Curb because he too comes out of show business?

“Well,” Reagan replied, “that didn’t hurt any.” The streamlining of the Republican image was thus assured. The leap had been made from Bedtime for Bonzo to “You Light Up My Life.”

When he finally arrived, Mike Curb was by far the youngest person on the dais, but none of the Explorere Scouts had ever heard of him. During lunch Curb played the respectful acolyte. He was introduced by chairman Wally Thor as “an articulate advocate of our free enterprise system.” Then Curb rose to introduce Reagan. Neither he nor the former governor ever mentioned scouting. “He left us with an $800 million surplus,” Curb told the audience of corporation presidents. “He believes in motivation and incentive.” When he spoke Mike Curb’s hands jutted out awkwardly. “He’s a man who I think is destined to be the greatest man America has had in years and years and years – the finest man I know – Ronald Reagan.” “I wish they’d talk about scouting,” said a committeeman.

A few days later, at an Optimist luncheon at the Los Angeles Statler Hilton, Curb and his fiancée were again the youngest people on the dais. To warm applause, Curb gave what was to become his standard speech.

“When I started my own business twelve years ago,” he said earnestly. “I remember hearing, ‘Be careful what you strive for – you might achieve it.’ ” The message was clear – he had. Curb then went on to tell how he earned $3,000 for writing the jingle, “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda.” He told how he began his first business, how he and his sister lived in the janitor’s quarters of their office building because they couldn’t afford the rent for an apartment. He then segued into a section about how businessmen should serve in the legislature for a time and then, as legislators, they should get out and “live under the laws they pass.” He made it sound as if Sacramento were an independent city-state. Curb then stressed that young people today were basically “giving up.” He said, “They know they won’t get jobs. They hear, ‘Small is beautiful.’ They hear, ‘Lower your expectations,’ and it has a detrimental impact. . . What exists on these campuses I’ve visited is a total lack of understanding of our system, and businessmen are not respected by their own families . . .”

The message is clear: Trust me, trust my face, trust my background, and I will bring back the old verities. I’m a success. I’m an example. I’m not a politician. I can attract youth. I can get jobs. I can be a dynamic new image for the party. “Linda,” the Optimist emcee said to Curb’s finacée, “we’d like you to take that floral centerpiece home.” Linda smiled and said nothing.

Later that night, at a fat-cat fund raiser in Rolling Hills, Curb told a small group that deregulation across the board was the answer to California’s energy problems, and a man answered, “Amen.” Then Curb returned to a favorite theme: “We must find new ways of packaging issues.” Curb constantly tells his audiences that Republicans are regarded as being against everything. “Republicans must express their philosophy positively.” As he moved around the room, Curb was earnest but disconnected. He’s there and he’s not there. It’s as if there’s an invisible plastic shield between him and the person to whom he’s speaking. “Hi. Nice to meet you! Hi.”

Finally, the third fund raiser of the day, a Long Beach dinner to help Republicans in two assembly districts. This time, Curb, driving his own baby-blue Continental, was 40 minutes late. He had no bio card to give the chairman and so he was introduced as the president of MGM Records, a post he gave up four years ago. The he gave The Speech. “We lost the governorship and lieutentant governorship last time by less than 174,000 votes statewide.” Curb admonished. “We have to make it up with our 18- to 34-year-olds.”

But, alas, just about the only 18- to 34-year-olds in the audience were singularly umimpressed with Mike Curb. “He didn’t say anything new really,” offered Roxanne Rayburn, 20. “I really didn’t listen,” said Debbie Guevertz, 25. “I don’t even know who he is. Debby Boone and Shaun Cassidey can only help with people who are too young to vote.”

On Washington’s Birthday, Mike Curb announced officially for lieutenant governor. He gave the standard stump speech with a few new twists including the line. “The Force will be with us.” And, in an attack on the man he would likely face in a general election, current lieutenant governor Mervyn Dymally, Curb said, “He is virtually invisible except for periodic appearances to avoid scandal.” Refusing to be specific when reporters asked what scandal he was referring to, Curb cited “previous media stories” about Dymally. “You’re resorting to classic political demagoguery,” a newspaper reporter told him. Mike Curb seemed surprised. He is accustomed to appreciation and maybe he thought he’d never be scrutinized. But it turns out that Mike Curb, and particullary his choir-boy image, can indeed bear some scrutiny.

Mike Curb was born in Savannah, Georgia, the son of an FBI agent who moved the family to Compton, California, when Mike was five. Mike and his sister, Carol, fifteen months younger than he, have been closer than most twins. Except when she attended college, they have always lived together, even sharing a home with Carol’s first husband, and now with her second. Mike grew up playing the piano and administering two papers routes. “He ran them like a business,” Carol says. “It seemed he was old before he was young.” “He always seemed to enjoy adults a lot,” said his mother. “He loved to talk to grownups more than kids,” Curb is “a great seducer of older men,” says one record company executive, “in that he’s able to convince them he’s today’s answer to young people.”

Almost as soon as he sold his first music — $3,000 for writing the Honda jingle – Curb dropped out of college to start his own company, Sidewalk Productions. The company did a lot of work cutting soundtracks for motorcycle and beach-blanket B movies. Carol took the job as Mike’s secretary and the two worked long hours. “Mike wanted a nice suite of offices and the rent precluded us from having a nice apartment,” says Carol. “So we slept in the janitor’s room. Mike felt the front of the office was more important than where we would sleep for a few hours.”

Curb owned Sidewalk Productions from its inception in 1965 until 1968 when he sold the company to Transcontinental Investing Corporation. Although Curb likes to date his first million from the time of his sale of Sidewalk, Robert Lifton, chairman of the board of the now defunct TIC, recently said, “Mike didn’t get near a milion in stock and the stock he got was unsaleable for three to five years.”

Curb’s new job was to start a record label for Transcontinental. But the label never got off the ground, because of difficulties with record distribution – a problem outside Curb’s bailiwick. Curb was working eighteen-hour days, six days a week. “His Sunday relaxation,” says Todd Schiffman, who had worked with Curb, “was to go to the studio and cut bubble-gum background music for Saturday afternoon kiddie shows. I thought it was an atrocious waste of time to produce that drivel. We never argued about it, but we didn’t see each other for three years. Mike doesn’t like to be criticized.”

As his dream at Transcon crumbled during 1969 and 1970, Curb found his salvation in a new mentor, James Aubrey, who had become president of debt-ridden MGM. Curb met Aubrey throught an agent who served both men, Bill Belasco. Belasco, who died last year in a car crash, was, by all accounts, a strange character. Openly gay, he was given to throwing kinky Hollywood parties. Producer Micheal Viner, who worked at MGM says, “He took Mike at a very young age under his wing.” “Belasco was unquestionably a door opener for Mike,” says Fredric Gershon, a prominent entertainment attorney who represented Curb. “I don’t know if they were always good doors.”

In 1969 Aubrey and Curb began doing business together, with Curb Records and receiving a 20 percent equity in the company. Curb inherited a company $14.5 milllion in the red and in a year, helped by massive cutbacks and firings, he was able to turn it around to show a small profit. Curb’s four-and-a-half year tenure at MGM, however, was uneven. His greatest success was taking a group from the Andy Wiliams show, a group with a barbershop-quartet style, and turning it into The Osmonds. In fact, Curb, who personally produced all of the Osmond records, became so closely aligned to them that he was known as “the sixth Osmond.”

The sixth Osmond was not exactly what some other MGM groups had in mind for their record-label president. So when Curb began denouncing drugs, his stand – and his taste in music – offended his largest selling act at the time, Eric Burdon and the Animals. Burdon admitted smoking doped and said he wanted to leave the MGM label. Along with scores of others, Burdon picketed the MGM offices carrying a sign that said, “I am a victim of MGM’s plastic fascism. Release me.” Curb had announced he would drop any MGM performers admitting to drug use, but most people in the business charge he meant only those that weren’t selling. Curb would not let Burdon out of his contract. “Eric Burdon never came to me and asked me to get off the label,” Curb said recently. “That’s not true,” counters Steve Gold, who was Burdon’s manger at the time. “We constantly asked to be released from the contract. We finally sued MGM for release and nopayment of royalties,” After two years MGM stopped fighting Burdon’s release. The royalties suit is still pending.

By 1974 MGM wanted out of the record business. “I don’t think we ever solved all the problems there,” says Curb. “It would’ve been easier to start from scratch.” “Mike grew up a lot at MGM,” says Schiffman. “It was a very sobering experience.”

MGM Records was taken over by its European distributor, the Polygram Corporation, which already owned Mercury and Polydor Records. Several months after purchasing the MGM label, Polygram bought out Mike Curb’s contract. Whether Polygram got a good deal is subject to question. The Osmonds were the only red-hot act on the label at the time Once again, it could be aruged, Curb had “failed upward.” He was certainly a millionaire by now.

In his time with Polygram, Curb claims, he never had any interest in pursuing an executive position with either of the other labels owned by the corporation. But that claim is subject to dispute. Periodically, over meals, Curb and some cohorts discussed his becoming president of Polydor and Mercury. To open the way, they fed information to columnist Jack Anderson about the man who was already Polydor’s president, Jerry Schoenbaum. The information given to the Anderson people alleged that Schoenbaum was paying black disc jockeys to get his records played on the air. When Les Whitten, Anderson’s assistant, told him the charges, Schoenbaum was furious. He convinced Whitten the charges were false and nothing was printed.

When they bought Curb out, the Europeans had him sign an eighteen-month noncompetition clause which stipulated that, except for producing the Osmonds for them, he would not work for any record company. It was during the time of the noncompetition clause that Mike Curb turned his attention seriously to politics. He had laid the groundwork earlier.

In 1967 Curb had formed the Mike Curb Congregation, some of whose members had been with him since his jingle days. When Curb’s political beliefs were widely disseminated through his drug stand at MGM, he began to get requests to provide enteratainment for certain political groups. “A lot of Republicans would call me or my sister if they wanted entertainment,” he says. “When possible, we provided it. And quite frankly the Congregation went over pretty good.” By 1972, Curb and the Congregation were meeting Republicans and community leaders, and Curb was happy to do so. “I’d be in the office putting on a tux, racing over there,” says Curb, who often performed with the Congregation as an organist and singer.

In 1972, Micheal Viner, a Washingtonian with lines into Nixon’s White House, was director of special projects at MGM Records. He had produced Sammy Davis Jr.’s hit single, “Candy Man,” and he asked Curb if Curb thought Sammy might perform for President Nixon. “So I spoke to Sammy,” says Curb, “and Sammy agreed to do it. Sammy went back and that’s when he put his arms around Nixon. If you remember, the Mike Curb Congregation was performing. I was on the stage at the time.” That year the GOP called on Curb to supply entertainment for 25 events. “It wasn’t very easy to find,” says Curb. “I’d use Pat Boone, The Osmonds, Eddy Arnold, Hank Williams Jr., the Mike Curb Congregation.” Julie Eisenhowever was reported to have said, “If I have to hear the Mike Curb Congregation one more time, I’ll puke.”

But supplying talent paid off. Curb was co-master of ceremonies with Billy Graham at the 1972 inaugural festivities. In 1973, the Mike Curb Congregation performed at a state dinner for King Hussein. “I was invited to the White House to talk to the President,” says Curb. “Actually, he asked me my thoughts on how he was communicationg with young people.”

“Nixon believed in Curb,” says Viner. “Mike nurtured and put a great deal into that relationship. If Nixon had survived, Curb would have been very importatnt. His downfall was a blow to a lot of time and effort Mike had put in.”

Most of the people who have known Curb well for ten years or more say that he has had long-time presidential ambitions. And by 1974, he was ready to take a first step. He had already become the chief fund raiser and chairman of a Rebulican group called the Statesmen – big donors to the GOP. In that capacity he became friendly with the inside power brokers of the party such as Holmes Tuttle. It was Tuttle who brought Curb to Reagan in early 1974 by introducing them at a fund raiser at Curb’s house in Trousdale Estates in Los Angeles. For a year and a half Curb organized support for Reagan, and was then named Republican National Committeeman.

When Reagan lost the nomination, President Ford invited Curb to Vail, Colorado, to ask him to be co-chairman of the Ford-Dole Executive Committee in California. After checking with Reagan, Curb said yes. He was able to talk 57 of the 58 Reagan county chairmen into supporting Ford, and not only did the unified party deliver California to Ford, it was also a big factor in S.I. Hayakawa’s victory in the U.S. Senate race.

A few months after the 1976 elections, Reagan’s finance chairman, Jack Courtemanche, who had worked with Curb on the presidential campaign, told Curb he should consider running for statewide office. Other people in the party did too. Courtemanche, who is now Curb’s campaign chairman, is very proud of his candidate. “You should see him with rock trivia,” he says. “And when we take him to Leisure World, the old people go crazy.”

In early April 1977, Curb’s backers formed the Friends for Mike Curb committee and got grass-roots people in both the Ford and Reagan wings of the party to raise money. Beyond the grass-roots support, big names from the Reagan kitchen cabinet and the enteratinment world dominate Curb’s committees. He has secured the endorsements of most major Republican candidates running for statewide office, among them Pete Wilson, Ken Maddy, Evelle Younger and John Briggs. “Mike used his business – entertainment – as a unifying tool,” says Courtemanche. “The gubernatorial candidates all saw the handwriting on the wall. They all ended up supporting Curb.”

“I made a complete investigation of Mike,” Holmes Tuttle says, “and I’ll do anything I can to help. Mike’s a good, sound conservative. He’s concerned about the system and wants to help. He can go on college campuses and he’s not classified as anything.”

“They’re real spoilers,” says Assemblyman Antonovich of Curb and his supporters. “They’ve put ambition over logic and common sense. I’ve been taking public positions for nine and a half years. I don’t know where he stands.” Antonovich, a leading young conservative who has never lost a race, was minority whip of the State assembly and has been out front for the conservatives in the Assembly on a number of their pet issues. He is Curb’s only opponent in the primary.

A few months ago there were four potential opponents. State Assemblyman Ken Maddy is now running for governor. State Assemblyman Dixon Arnett is running for controller with the help of Curb’s money people. And Bob Wian, the founder of Bob’s Big Boy Hamburgers, dropped out of the 1978 races completelty a week after a meeting with Curb at the Smokehouse restaurant in Burbank. Antonovich says Curb tried to presssure him, too, out of the race at a meeting in a West Los Angeles restaurant last fall, a charge Curb denies.

Curb recently insisted that he wants primary opposition: “My campaign people think I should have an opponent or else I won’t be judged a winner.” There are various scenarios about the importance of the current lieutenant governor’s race. Because Jerry Brown might either run for president in 1980 or be on Carter’s ticket as vice-president, whoever becomes lieutenant governor in 1978 will be in an excellent position to be governor of the state in two years. Republicans also think that while Brown will be tough, Dymally can be taken. “Lieutenant governor’s the one to win,” says Antonovich.

The worst mistake anyone could make about Mike Curb is to underestimate him. “I used to thing he was a fluke,” says Pat Boone, “that he was naïve, like a child. But you think he’s not paying attention to you, and he’s always soaking up all the information, like his antennae are perpetually out there. Mike is like a cat. It doesn’t matter which way you throw him in the air, he comes down on his feet.”

“He’s a rough, tough dealer,” says attorney Fredric Gerhon. “He’s very careful how he chooses his words and can moralize or justify whatever he does no matter how it turns out. The boy is a powerful force.”

Curb’s power produces a certain paranoia in the music business: many people in it don’t want to talk about him. “We have to work in this industry,” is a common excuse.

Curb can soft pedal, as well as be tough, to serve his means. Recently, in defense of his attacks on Dymally, he said plaintively, “Look, people want to say that if you’re in the record business you’re on payola. Or you’re into drugs. Dymally, out of a clear blue sky, says ‘You ought to look into Mike Curb.’ People say, ‘Do you have any specific allegations?’ And he says, ‘No I think you ought to investigate him,’ Of course, I can’t criticize. That’s sort of what I did, too.”

Another day Curb telephoned a reporter he feared might be writing something unfavorable about him. The tactic Curb chose was that of shy teasing. “Look,” he said, “you’re gonna at least let me win the primary, aren’t you?”

“He’s really a shy person and a private person,” says Todd Schiffman. “The best thing that could happen to Mike is if he lost because then he could start livng his life a little. He could relax. He’s never really had a life of his own. On a personal level I almost wish he’d lose.”

Up in his big Trousdale house with its unassuming utiltarian furnishings and a pool that looks as if it’s never used, Curb is torn between politics and pop music. Unilke most politicians who never get enough political talke, Curb would rather discuss music. “My favorite thing when I am campaigning up north around these little towns,” he said recently, “is to turn on the radio and see if my promo men are telling the truth. Are they really breaking a certain record in Yuba City?

“I fly up to San Francisco to do a rodio show. And the DJ askes me, ‘Okay, Mike, you’re running for lieutentant governor. What do you want to alk about, the issues or rock trivia?’ ‘Oh,’ I say, ‘lets talk about rock trivia.’” If Mike Curb wins, he will be the first lietunen goven Californians ever had who know the flip side to “Da Doo Ron Ron.”

To older men in the GOP, like Holmes Tuttle and Tex Talbert, Curb has given the impression he will sell his reocrd company and be a full-time politician. But his sister says no way: “Mike will never give up his business for politiics. It will be both of them at the same time.”

“I hope he can continue to cut Debby’s records,” says Pat Boone.

Such an agreement may not be ethical, but it would be unique, and could serve Mike Curb quite well. His qualifications for the office he seeks right now are questionable, but he has come very far, very fast, and who knows how much further he can go following his formula for turning top-ten hits into political clout? A while ago, two drunks were standing outside a Long Beach restaurant as Curb entered to speak at a fund raiser. “What’s going on? Who’s he?” one of them asked.

“He’s Mike Curb,” someone said. “He’s running for lieutenant governor.”

The drunks drew a blank.

“He’s the guy that produces Donny and Marie and found ‘You Light Up My Life,’” they were told.

“Really?” one asked. “Then, he should go for governor.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.