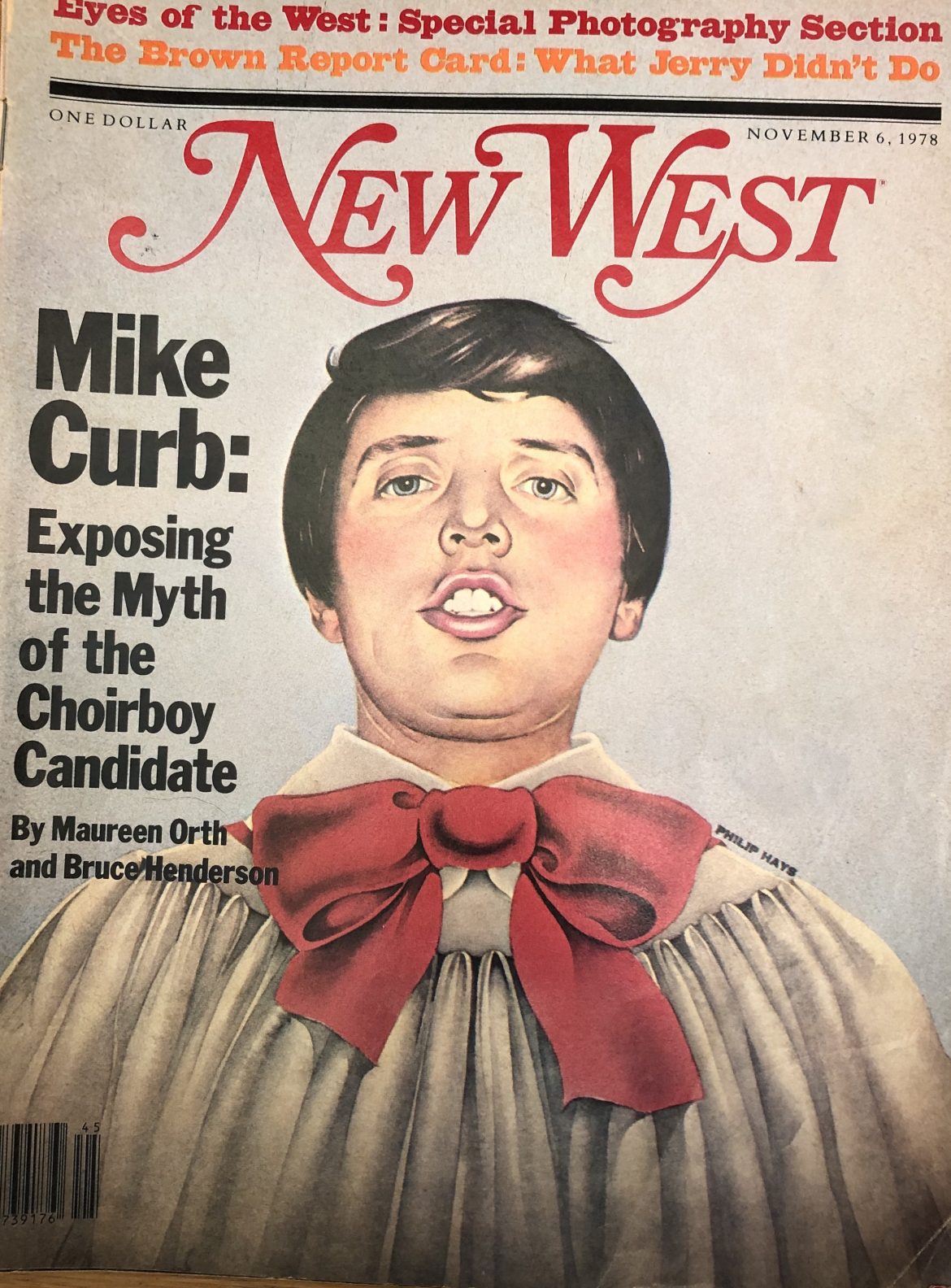

Original Publication: November 6, 1978. By Maureen Orth and Bruce Henderson.

“Mike Curb will help the working man, the senior citizen, everybody,” announces one TV commercial. “He’s active, he’s dedicated, he has good, sound judgment,” proclaims another. “I think he best represents all of our interests,” says the man on the street in a third TV spot. The airwaves are inundated with paid announcements depicting Mike Curb as a Christian businessman, a self-made millionaire, a person tainted by nothing and rich in achievement. An intensive investigation by New West finds these announcements arguable. “Building a business is much tougher than building a political career,” Curb said on Day One of his campaign to become California’s lieutenant governor. Here are some of the ways in which he built his business:

- When he was staff producer for Mercury Records in the mid-sixties, Curb—according to his immediate boss there—was caught billing his employer for studio time that was actually spent working on records for Curb’s own independent production company, the existence of which his superiors at Mercury knew nothing about. The immediate boss told New West he warned Curb that those actions constitute “grand larceny”.

- In the late sixties, Curb negotiated for weeks with Paramount Pictures to buy prime studio property. When required to come up with a token payment to show his good faith in the negotiations, Curb gave Paramount a bad check for several thousand dollars.

- In 1969, after merging his Sidewalk Productions with Transcontinental Entertainment Inc., Curb wanted independent producer Chris Huston to become part of TEC. Curb told Huston to form a company. Curb said he would then arrange for TEC’s conglomerate to buy Huston’s new company for $2,175,000 in stock if Huston would kick back to Curb a percentage of the stock.

- From 1969 to 1971, Curb was twice placed on AFTRA’s unfair list, an action which forbade union members from working for him. He was put on the list after AFTRA performers complained of not receiving minimum payment for their services. In 1977, another complaint was filed with AFTRA, this time by members of Curb’s own Mike Curb Congregation singing group, who charged Curb had underpaid them $2,400 for a recording session. The singers later withdrew their complaint, telling AFTRA people that they were told they’d never again work for any major record companies if they made trouble.

- In California alone Curb has been named, or figures prominently, in sixteen lawsuits with a range of charges from breach of contract to fraud and conspiracy. In the past two weeks, he twice has been threatened in writing with new lawsuits that would charge breach of contract and unfair competition.

- While serving as president of MGM Records—from 1970 to 1973—Curb was responsible for financial irregularities, discrepancies, excessive billings and substantial budget overcosts, according to a former MGM administrator who eventually lost her job after constantly questioning the authenticity of bills for sessions of the Mike Curb Congregation.

- In 1976, after Curb was fired from his MGM Records post, the company was forced to pay an $8,000 settlement because Curb had claimed, in a letter to producers of a TV special, that his group, the Mike Curb Congregation, had the performance rights to a popular title when in fact it did not.

- In 1968, a rock group called Boston Tea Party agreed to record an album for Curb. According to the group’s manager, the group was to receive at least $4,000 payment for studio time, plus future record royalties, but none of this money was forthcoming even after the album was released.

- This month, Curb received a letter from the Grey Advertising Agency, threatening him with legal action if he does not stop making the claim that the first success of his career came when he wrote the commercial jingle, “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda.” The ad agency conceived the campaign and the copyline in 1963, a full year before Curb’s participation. Curb’s contribution was to write the music for the radio spot. The agency claims that Curb has twice before ignored its “cease-and-desist” demands. Curb has refused to discuss this fact—or this entire article—with New West.

Mike Curb’s manner of doing business began early. One of his first bosses, Doug Moody, met Curb in 1966 while Moody was director of A&R—artists and repertoire—for Mercury Records. At the time, Curb was an assistant staff producer for Mercury. “Curb had surreptitiously started his own production company, Sidewalk Productions,” says Moody, “and when he went into a studio, he’d make a recording for Mercury and another one for his own company which he’d also have Mercury pay for. This had been going on about a year when I found all these strange billings. I confronted Curb and told his what he was doing was grand larceny, and we could have him put in jail. We didn’t want a big legal stink, but he built his own label compliments of Mercury.” Curb was kicked off the company payroll, according to Moody, and was informed that henceforth Mercury would use him strictly as an independent producer. Moody says he remembers sitting with Curb in a car in a parking lot on New Year’s Eve, 1966, and telling him: “Mike, I’m giving up my New Year’s Eve to talk to you—to try to straighten you out.” To help Curb, Moody and Mercury assigned to him the two Osmond Brothers, who were then—in Moody’s words—“just a couple of little kids.” The deal was for Curb to produce their records independently, for distribution by Mercury. “I told Mike to live with them, learn how to handle them and don’t lose them.”

During the next few years, Curb put together album and soundtrack deals with numerous companies, always managing to attract young, beginning artists and studio musicians who would work for little or no salary with the promise of future royalties. But for some, those royalties never materialized. One childhood friend of Curb’s, Larry Brown, had to sue Curb’s company, Sidewalk, in an effort to collect royalties for eight years of work. When Curb failed to produce financial records, Brown ended up agreeing to a lump-sum settlement. “We were all young and stupid, and he took advantage of us,” says a producer. “His game was to let you sue and sweat it out for years, waiting to get to court. Then he’d settle before it went to trial.”

According to dozens of people who have done business with Curb, he has always been hard to pin down on money matters. “He’d say he’d take care of it and pass it along to his lawyer,” says one producer. “Then his lawyer would say he’d have to check with Mike, Curb has a real knack for ignoring you when he doesn’t want to listen.”

On February 13, 1969, Curb and Sidewalk Productions were placed on AFTRA’s unfair list. Seven months later, they were taken off the list when Transcontinental Entertainment Corporation acquired Sidewalk and Curb said that Transcon would assume Sidewalk’s back debts. But those debts were never paid, so Curb was put back on the AFTRA unfair list in 1970 and remained there—even after he became president of MGM Records—until December, 1971. At that time, he agreed to pay $1,462.50 worth of back pay, plus additional union benefits, to four AFTRA performers, and was taken off.

Among the people Curb worked with was Robert Carl Cohen, who produced and directed the film Mondo Hollywood. The co-produced an album for Sidewalk Productions, Unpredictable Gypsy Boots and the Nature Boys, distributed by Tower Records. Says Cohen: “I had a 50-50 producers’ deal with Curb, but I never received any royalties. I finally asked his lawyer why I wasn’t getting any producer’s royalties on it. He said the album hadn’t made any money.” Today, Cohen, who has never received any money on the album, is still after Curb and the lawyer to give him, at least, a report on whether Curb ever received a producer’s delivery fee which the agreement called for Cohen to share in. The producer’s delivery fee is the money Cohen believes Tower Records paid to Sidewalk Productions, under traditional record-business procedure, upon delivery of the master tape for the album. Says Joe Smith, chief of Warner Communications’ Elektra-Asylum label and the man who negotiated the deal that set up Curb’s current firm, Warner-Curb: “A producer, if he delivers us a master, will get a fee. He’s got to get a fee because it’s his salary while he’s working. It’s an advance against royalties. Oh, sure. Absolutely. It’s common procedure.”

Cohen recently discussed his experiences dealing with Curb: “The lawyer made Curb’s contracts. Curb himself never talked about business deals. He’d always say that’s for the lawyer. Curb had this blank stare he’d turn on if you pushed him. He was so well greased you couldn’t get past this façade, especially if you were trying to find how much money was in a deal for him and for you. When I started not getting reports on the Gypsy album, I figured that they had this system worked out and I would never get paid.”

At Sidewalk, Curb had a deal to score and produce soundtrack albums for American International Picture’s B-exploitation films, some of which he invested in. Some of Curb’s former associated claim they were not paid proper payment for their work on these AIP film soundtracks. “I didn’t receive any payment for a Cycle Savages number of mine,” says songwriter Randy Johnson, “even though they used it. You have to understand that Curb didn’t run normal companies. You didn’t get paid when you were supposed to.” In 1971, even AIP had to sue Curb and one of Curb’s publishing companies. AIP charged that Curb had breached several contracts over a four-year period, had failed to pay royalties to AIP for its share of the soundtrack rights.

Jim DePerna, manager of Boston Tea Party, says he never received any sales reports on the group’s 1968 album for Curb, despite continuous requests to get such information. Curb produced the record independently, and it was released on an MGM label. DePerna says Curb was to receive a fee from MGM upon completion of the album, and was to then pay for the group’s recording time, which ultimately figured out, DePerna says, “to at least $4,000.” DePerna says one of Curb’s associates told him Curb got paid “and never paid us. I never sued him because the group had a lot of potential at the time and I wanted to get away from him. We just chalked it up as a loss.” They never received their money for recording time or any royalties.

One person who did sue over the Boston Tea Party album was photographer Tom Denove, who—after an exhaustive effort to serve papers on Curb—got a judgment against him in small claims court for pictures of the group that Curb solicited and never returned nor paid for.

Even while nickel-and-diming over promotional photos on the one hand, Curb thought big on the other. Among his dream deals was an effort to buy a prime parcel of studio land in Hollywood owned by Paramount Pictures. The property already had several sound studios on it and would have been an excellent location for a recording complex. The asking price was more than $2 million. After a series of conversations over a five-or-six-week period, without Paramount having received any money from Curb, the late Seymour Adler, head of Paramount’s television operation, reportedly required Curb to come up with some “good faith” money in order to continue negotiations. Late on a Friday afternoon, Curb handed over a check for several thousand dollars. Adler immediately called a friend of his who was an official at Curb’s bank and asked if the check was good. “Don’t even bother to deposit it,” Adler later recalled the banker telling him. “There’s less than $10 in his account.” A Paramount consultant who was involved in the negotiations remembers: “This type of thing had been going on for months with Curb swearing up and down he’d do something and never coming through. Finally, with the bad check, Paramount threw up its hands and said to forget it, there would be no more negotiations with Curb. I can still remember those baby-blue eyes staring at me and his assuring me the check was good.”

A few months later, Curb entered into an agreement with Joseph Justman for Justman to buy the Paramount property for $2.7 million on behalf of both of them. In a partnership agreement, signed on August 2, 1968, Curb agreed to come up with $700,000 within six days, and secure a line of credit, not to exceed $300,000, for working capital. According to a legal action filed later by Justman, Curb failed to live up to the agreement. A short time after the suit was filed, Justman died.

Curb’s official biography states how he got the money to begin his first business: by writing the song, “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda.” It is a story he commonly tells on the stump, too. Actually, Courtenay Moon, vice-president and senior creative officer at Grey Advertising, conceived the print campaign a year before Curb was ever involved, and the advertising agency has notified Curb, through its attorneys, that if he does not stop claiming credit, the agency will sue. As a subcontractor for the agency, Curb wrote the music for the radio spot. “Our lawyers have written Curb twice to cease and desist [from taking credit],” says Moon. “We should have sued when he started this in 1966, but we figured our clients, the Japanese, knew the difference.” They did. “When Curb came to Japan with the Mike Curb Congregation, he called Mr. Honda and wanted to meet him,” says Robert Humphreys, president of Grey’s western division, “and said he was responsible for the campaign. But Mr. Honda checked and learned the truth. Mr. Honda refused to see him.”

In the late sixties, Curb went to his old boss, Doug Moody, and offered him 2.5 percent of the gross of any new business Moody could bring Curb’s companies. Moody accepted, and spent time at Curb’s house where Mike lived with his sister, Carole Curb. According to Moody, Curb would regularly practice hypnosis in front of a mirror. Moody decided this “was to induce control over himself, so he could still look you in the eye while he made all those deals. Once, I heard a crash and Carole came out and told me, ‘Mike had an accident.’ He had bashed the mirror in.”

Meanwhile, Moody was in the process of negotiating a deal for Curb’s company, Sidewalk, to do music publishing and movie soundtracks for Transamerica and United Artists Music. Curb had given Moody authority to act as his broker and make the deal on behalf of Sidewalk. “We were going to make $200,000 on it,” Moody says. “Then all of a sudden Curb tells me he’s made a deal with Transcontinental. I think he used my paperwork to make the deal. He told me I was out. He screwed me, then tried to buy me off.”

The deal Curb made with Transcontinental Investing Corporation (TIC) was as follows: The conglomerate would buy Sidewalk Productions and Curb would become president of a subsidiary of the conglomerate, which would be called Transcontinental Entertainment Corporation. TIC, the parent corporation, already had another subsidiary, Transcontinental Distribution Corporation, which owned retail record outlets. TIC wanted to get into the production business to supply their “racks” with product: records. The creative, or production, end would be Transcontinental Entertainment, headed by Curb.

Now Curb really began to roll, offering astronomical sums of the parent company stock to producers if they would create companies to bring out records for Transcontinental. To appease Moody, Curb offered him a stock deal, too. He first offered Moody $2,175,000 in Transcon stock over a seven-year period for a company Moody would create. According to Moody, the understanding was that some of the stock would be kicked back to Curb personally. Moody agreed, set up offices, and called in British producer Chris Huston to help create the company. Without Moody’s knowledge, Curb took Huston to New York a short time later and made a similar, $2,175,000 deal with Huston alone—including a kickback. Then he withdrew from his deal with Moody. “He aced me out a second time,” says Moody. Why had Moody continued to do business with Curb? “To this day,” says Moody, “I don’t know why. Mike can take three shots at you. He would apologize for the way he had to do things or treated you. He was like a little boy.”

Huston set up shop, calling his new business Chris Huston, Ltd. Huston says that he and Curb then met with Transcon officials in New York, where Huston signed a contract that called for him to receive the stock and a modest, guaranteed annual salary of $17,000 from Transcon. “Mike told me I had to kick back 25 percent of the stock to him,” Huston says. “That was all right with me.”

Part of the deal was for Huston to get Mystic Sound studio in Hollywood—for which Curb held the lease—so Huston would have a place to record. When Huston visited the studio, before signing the agreement, it was fully equipped and ready to go with a modern, eight-track machine. “When I visited the studio,” recalls Huston, “Mike said, ‘This is it, it’s yours.’” But when Huston returned from New York to start his new operation, the studio was empty. All the equipment had been moved to another studio Curb owned. Says Huston, “I certainly had the impression I was going to get the equipment, too.” Huston called Curb, who promised to send over more equipment. Curb did, and a week later Huston got a bill, charging him $100 a day for the rented recording machines. “We ended up paying for several rental bills,” says Huston. He says he tried to send some of the bills to Curb, only to have Curb disappear on him. “When I couldn’t find him, I had to pay the bills myself or lose the machines and not be able to record,” Huston says. Six to eight months passed, without Huston receiving any paychecks or stock. He lost the house he was renting and his car. He never did get his checks or stock.

After a year, the parent conglomerate decided Transcontinental Entertainment wasn’t doing well enough to continue. Eventually, Transcontinental Entertainment dissolved and the parent stock—for other reasons—proved worthless.

But Curb had once again landed on top. James Aubrey, then president of MGM, had brought him in to head that company’s ailing record division. When he became president of MGM records and a stockholder in the MGM corporation—and while still a stockholder in Transcontinental International—Curb implemented an arrangement he’d insisted upon as a condition of employment at MGM: To bail out Transcon’s distribution subsidiary, which was not doing well, he had TDC distribute MGM records for 15 percent of MGM’s gross sales. Within a year, MGM sought to buy back the distribution rights, and it cost them around $1 million to do so. “Curb’s decision to have Transcon distribute for us was a disaster,” says Andrew Benson, currently director of internal audit at MGM. “Their collection effort was not as good as ours.”

As president of MGM Records, Curb received a salary and stock. He was allowed to collect publishing royalties on songs he co-wrote, which were recorded on the MGM label. And he continued to produce the Osmonds and the Mike Curb Congregation. “It was the Osmonds who were actually carrying the whole label,” says a person who worked there. Curb had signed many older, middle-of-the-road acts—including Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme and Robert Goulet—and none of them was selling huge amounts of records.

At Curb’s side were Richard Whitehouse, his lawyer, who was serving as executive vice-president of MGM Records, Curb’s sister, Carole, and on occasion Curb’s father—an attorney for Continental Oil—who was called in for special decisions. Curb moved quickly to hire close friends for independent production deals, and production budgets often went over by more than 100 percent. Expenses also ran high. “I questioned expense accounts often to Whitehouse,” says Ed Beulike, the former vice-president of administration of the music division of MGM. “I said I would not approve them and sent them to corporate without approval. I didn’t agree with them, but I didn’t have the power to turn them down.” MGM corporate brought in a man to try to keep the fiscal reins on Curb. “When the corporation told Curb to get rid of his chauffeur,” says Beulike, “he kept him by putting him in the mailroom. But he continued to drive Curb places.”

Joan Brown Olesen, an administrator at MGM under Curb, says, “We were upset. He’d cut corners, was resistant to procedures and didn’t pay attention to budgets. We figured, okay, it’ll take him two years to learn, but he never learned how…Mike’s not a good businessman. If you’re a good businessman, you don’t have your friends all over the place. That’s why MGM went down the tubes—there were too many friends around.”

Curb’s political aspirations became apparent during his MGM days. Crucial to his political needs was the Mike Curb Congregation. Eventually, his ability to provide the Congregation for Republicans fund-raising events gained him entry into the highest GOP circles, and undoubtedly helped lead to his own candidacy.

The Congregation was not signed to MGM, but to one of Curb’s own companies. Each member—as many as 21 at a time—was guaranteed a minimum salary of $250 per week to be paid from that company. As MGM Records president, Curb hired his own group to sing back-up in the recording studio for as many MGM acts as he could, and if they earned $250 a week in studio time, he was then free and clear of his financial obligation.

In addition to other financial duties, it was Joan Brown Olesen’s job to administer the reports of the time spent in the studio by the Congregation. Almost immediately she began to notice that bills submitted by Carole Curb for the group’s time often did not jibe with studio logs. “I was getting daily bills for the Congregation singers that would claim more time than the corresponding bills for studio time,” she says. Olesen could not figure out how, if the Congregation’s studio had been in use, say, only two hours, the Congregation itself could have been working in that studio for four-and-a-half hours. Olesen says she once complained to her boss about a questionable bill and was told, “Don’t argue about it—pay it.” Says Olesen: “It began to rankle me that I had to put my signature on things I knew to be wrong. We’re talking about several thousand dollars a bill. Every time a bill was turned in, it amounted to a couple of thousand dollars. Then Mike started sending bills for his or his friends’ sessions directly to MGM, Inc., with his okay on it, and they would buck it back to me. If I questioned it, he got mad. Eventually there were irregularities. My demise began when I started seeing discrepancies in bills that came out of Mike’s office. By the end of 1971, MGM, Inc., did not trust Mike. We began to hear stories that the record company was going to be sold.” Olesen was fired, she says, when she refused to approve a group of bills she describes as “outrageous.” She says, “I went to my boss, Eddie Ray, and said, ‘This can’t be.’ The following Monday, he said, ‘I have to let you go.’ I asked why and he shrugged his shoulders.”

Olesen’s charges are backed up by former MGM vice-president of administration Beulike. “I remember Joan coming to me and I think I told her to go back and tell Carole Curb that the reports don’t agree with the studio log, that we can’t overpay,” says Beulike. “But when it keeps happening, after a time, you’re just fighting City Hall and you get to be realistic about it.” Eddie Ray, Olesen’s boss after Beulike, denies her charges, dismissing her as “a bitchy woman.” MGM’s Andrew Benson admits, “If Mike attached an invoice, it could get paid.” But Benson refused a request from New West to probe further. Says Benson: “I’m not going to go in and look at the records. We’re a publicly owned company and I’m not interested in finding anything that will make us look bad. I can’t give you information that makes MGM look incompetent.”

Says one of the men sent in by the MGM Corporation to be a fiscal watchdog at MGM Records: “There was concern at corporate because the company was losing money. The recording costs were high, the advances were high, the overhead costs were high. The revenues were not sufficient to recoup the costs. Mike Curb may have been a personal millionaire, and he may have been a good producer, but MGM didn’t make any money under him.”

In the spring of 1972, MGM, Inc., was able to unload its record division on the Polygram Group, owned jointly by Phillips and Siemens, the huge Dutch and German corporations. Polygram already distributed MGM’s records in Europe and “the Germans”—as everyone at MGM referred to them—were high on Curb. “He got a piece of the company plus a salary,” says Benson. “The Polygram people wanted a prestige label and they were impressed with Steve and Eydie.”

Trouble soon developed between Curb and Polygram, however, because the Germans were even more cost-conscious than MGM, and Curb was continuing to sign acts frenetically. “At one point there were more than 300 acts on the label,” says a former MGM employee. “Curb would go around making all these deals on a handshake, and the lawyers were going nuts trying to keep up with the number of contracts.” Polygram officials were also reportedly upset with Curb’s increasing involvement in Republican politics. Even Curb’s executives protested when, after the 1972 election, Curb brought in Ken Rietz, who had no previous experience in the record business, and wanted to make him head of business affairs. Rietz had been chairman of Youth for Nixon. He is now managing Evelle Younger’s campaign, on leave from Mike Curb’s current company, Mike Curb Productions.

Reportedly, the Polygram officials were particularly incensed at the expenditures of Michael Viner, MGM “director of special projects,” who managed to spend about $1.2 million in a year and a half. It was Viner who first brought Curb into Washington, D.C., politics. Viner’s mother, a Washington PR woman, was influential in Republican circles. Viner once described her as “Nixon’s press agent,” and it was that link to the White House that Curb found so attractive. “Mike collects people he feels can be valuable to him for other purposes,” says an ex-MGM executive. Viner co-produced Sammy Davis Jr.’s only hit in years, “Candy Man,” but, according to one studio musician and arranger who worked under Viner, “he didn’t even know there was a hole in the middle of the record.” “He was a joke among the troops,” says an ex-MGM exec. By the time the Germans took over, Viner—thanks to Curb—had his own label at MGM: Pride.

Viner’s most flamboyant move was his chartering of an American Airlines 747 that carried a number of celebrities, including Bob Hope and Charlton Heston, to the second Nixon inaugural, of which Curb was named a chairman. After the inauguration, Viner submitted the bill–$40,000—as travel expenses. MGM Records eventually ended up having to exchange promotional services for the fee.

Several months later, Polygram, fed up with its big-spending record-company president, pulled the plug on Curb. “It all happened quickly,” says one observer. “Curb and his father flew to Germany, came back and he was out.” Polygram’s short involvement with Curb reportedly cost them millions, and even today they’re still paying him off on his contract. Curb, who owned 20 percent of MGM under Polygram, continued to produce the Osmonds for them. “They wanted him removed from a position of control,” says one executive who worked at MGM under Curb, and remained there after the sale of Polygram.

After Curb was long gone from the company, MGM Records continued to foot the bill for some of his actions. One involved the unauthorized use of the song “Jonathan Livingston Seagull,” performed by the Mike Curb Congregation on a TV special in 1973. In a letter on his MGM president’s stationery, Curb wrote the program’s producer, “…let me assure you that you have the complete right to see these tunes on your show. MGM will indemnify you against any claim that should arise in the event anyone questions your right to have this song performed.” Actually, Curb, his group and the TV show had no right to use the song title. After the show, a lawsuit was filed against MGM Records by Pacific Indemnity Company, which insured the producers of the show against losses and claims. For rerun use, the producers were forced to delete the words “Jonathan Livingston Seagull” from the production number, at a cost of nearly $12,000. And in January, 1975, two years after Curb’s departure, MGM Records was forced to settle with the insurance company for $8,000. Attorney Dan Sklar, who represented MGM in the action, says it was Curb’s fault all the way. “He consulted with no one at MGM and didn’t care that MGM ended up paying $8,000,” says Sklar. “He’s a man without principle. He’ll say anything for the moment. He’s a scary person. If he’s going to run the government like he runs business,” says Sklar, “we can expect a great deal of dishonestly and a lack of integrity.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.