Original Publication: New York Magazine, August 27, 1979

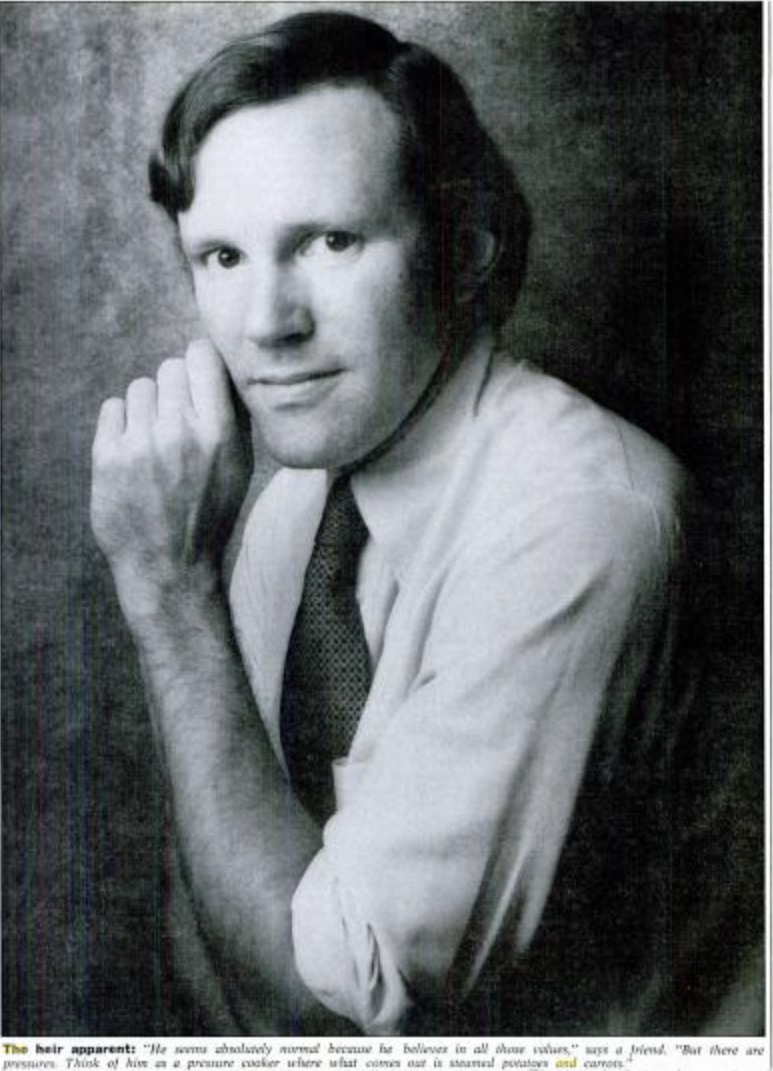

“. . . Now that 34-year-old Don Graham has taken over the Post, he has become one of the most powerful men in Washington . . .”

Katharine Graham, chairman of the board of the Washington Post Company, was sitting in her darkly elegant Georgetown library, talking about “the best job in the world”—being publisher of the Post. Last January Mrs. Graham named her son Donald, then 33, to take her place in that job. “You know publishers’ sons are famous dopes,” she said. Then she told a story about Don Graham—who was always called Donnie until his job titles got too big for diminutives. “Shortly after he arrived on the paper, I asked him, ‘Well, how is it being my son?’ He sort of shrugged and said, ‘Oh, it’s all right. At least you have one thing going for you: You can’t possibly be as stupid as people think you are.’”

Stupid he is not. “Thank God it’s he,” exults Joe Alsop, a close family friend, former syndicated columnist, and chief drumbeater for the Vietnam war. “He’s the ablest younger man of his time.” Alsop wore the expression of a wise old frog, who, by God, had maintained his position on the same lily pad for years and if he croaked you were supposed to listen. “I told them all to read. He’s the only one who took my advice.”

“Of course he’s rigid, forbidding, awkward,” says his best friend, Tim Mayer, an acerbically witty theater director. “Does he describe himself as that? Yes! But the noun is ‘Man’—seen that many around lately?”

Don Graham is the Prince Charles of Washington journalism, born to serve, carefully groomed, and dutifully diligent. He wears the armor of regulation Wasp; he is bright and enthusiastic in the face of huge responsibilities, and far more ambitious than he lets on. Yet to most he is also an enigma—this awfully nice, tensely wound, boyish-looking man with a manner so earnest it suggests either compulsive conscientiousness or that he’s got to be kidding. Soft-spoken and tall, with a tendency to blush bright red, Graham is usually surrounded by people far more colorful than he. Knowledgeable assessments of him range from “offensively Puritan” and “distantly rigid” to “absolutely first-rate”. Few think he’s easy to figure out. As the fourth member of his family in three generations to hold the title of Post publisher, his defense against the sneers and suspicions of being the prince regent has always been to hide under layers of self-effacement, gee-whiz good cheer, and impeccable control. Even when he hears a joke there is a split second when Don Graham does not react at all, when he is considering every explanation of what’s been said. Only then does he throw back his head and laugh.

“My whole goddamned life has been a soap opera,” says Katharine Graham, “and I don’t want to have him inherit it.” But that is precisely what is unavoidable about Don Graham’s life. As the quintessential inheritor, he carries the family banner; he gets all the power and wealth but he also has to bear the burden.

Everybody knows that his mother, who inherited the paper from her parents, Jewish philanthropist Eugene Meyer and his formidable German Lutheran wife, Agnes, is the reigning lady tycoon of America. She has presided over the Post during the heady triumphs of the Pentagon Papers and Watergate, reaping Pulitzers and the Hollywood glamour treatment. She’s also braved the chaos of a major strike. Now Don Graham, who’s grown up with the East Coast first string, surrounded by stars, high politics, and newspaper talk with the royalty of the business—named Lippmann, Reston, and Alsop—is faced with orchestrating an encore. Whether he’ll meddle with the Post’s lucrative formula (see end of article) or boldly expand the empire has got Washington guessing.

When he came of age in the sixties, Graham was the scion of the Establishment in an anti-Establishment time. By allowing himself to be drafted to fight in Vietnam right after Harvard and then becoming a Washington cop to learn the city, he proved he was shaped far more by his family’s empire than by the concerns of his generation. He has been a competent but diffident acolyte in his extensive training program at the Post. And as the happily married father of two little girls, he frequently indulges in lese majesty toward himself. He shuns the Georgetown social circuit; instead he and his wife, a lawyer, read the classics for fun, and in spite of being the heir to a $100-million media fortune, he rides the bus to work. So far he has been able to successfully walk the line between Establishment elders such as Alsop and trendier off-beats like Tim Meyer. But as publisher of the Post, he has automatically become one of the most powerful men in Washington and will have to take stands on controversial issues like nuclear power, future Vietnams, and his own company’s labor relations. Can Prince Charles stay Mr. Nice Guy?

Moreover, there are other, more immediate concerns. Today Don Graham still has to improve relations with unions, women, and minorities at the paper. He must also find the eventual replacement of brash and dashing 37-year-old Ben Bradlee, whom his mother chose to be her editor and confidant fourteen years ago. Looming over all this is Time Inc., which recently purchased the formerly weak crosstown rival to the Post, the afternoon Star. Time says it’s willing to lose $60 million in Washington over the next five years to become competitive with the Post.

Then, in addition to the corporate challenges, is a tangled web of family affairs that contains the seeds of a great American saga. Don Graham must maintain a good working relationship with his mother, whom he calls Kay. He must keep at bay the sibling rivalry with his older sister, Lally Weymouth, a New York writer and socialite, who’s known to be irked as not having a larger share of the empire. He is also big brother to 31-year-old Bill, who teaches law at UCLA, and 27-year-old Steve, involved in the theater in New York, neither of whom is in the family business. And he must face the long dark shadow of his father’s suicide in 1963—one of the keys, many believe, to Graham’s own restrained, highly controlled character.

“Analyzing Graham was almost an intramural sport at Harvard,” says Marty Levine, who was managing editor of the Crimson when Graham was its president. “Maybe it’s because he keeps so much of himself hidden. He is someone who has perfected the impression of being absolutely normal, not to escape notice but because he believes all these values to be absolutely right. We always felt there were pressures inside Donnie. Think of him as a pressure cooker, where you have very high pressure and what comes out is steamed potatoes and carrots.”

Don Graham is moving up and down the aisles of the vast Post newsroom, his dark eyes darting everywhere, making his once-a-week night rounds of the entire plant. He greets every reporter, as well as the cleaning people, by name. He inquires about their families, also by name. After he became publisher, reporters were surprised to find notes from Don Graham on their desks, congratulating them for a good story. “They were like little Oscars,” said one recipient.

Graham is noticeably silent, however, when he passes a group of union printers waiting to change shifts, and his silence is eloquent testimony that the convulsive Post strike of 1975-76 has left deep scars. This year several union contracts are up. Only in the last month, after more than three years, have management and the Newspaper Guild, which represents the editorial and commercial employees, come to an agreement. Unsurprisingly, Graham is viewed with suspicion by Guild activists who remember how much management was helped by the Guild’s voting to cross the picket line during the strike. “The only thing we have to go on is what we can see on the bargaining tables, and it has been a very hard line against the union,” says reporter Charles Babcock, unit co-chair of the Guild at the Post. “Donnie won’t win any Samuel Gompers awards.” “Donnie apparently feels he can separate himself personally from the conduct of some of the people acting for the company,” says veteran reporter Morton Mintz. “But can an active, involved owner of what is only nominally a public corporation divorce himself from the acts of his managers?” “He makes a point of being friendly and genuine,” says one Post editor, “but there are people who think Donnie is lying through his teeth.” “Look,” says reporter Karlyn Barker, the other Guild co-chair, “if Donnie were soft on unions he wouldn’t be there.”

The 1975 strike was Don Graham’s baptism by fire in the managerial ranks of the Post, the moment when it was no longer possible to have it both ways, being the media prince and also Mr. Nice Guy. The strike began with blood and violence in October of 1975 when a group of union pressmen destroyed property worth more than $200,000 and beat up a foreman. That attack would prove more costly for the pressmen. In December, when the pressmen rejected the Post’s final offer, scab labor was brought in to man the presses. The union was busted.

Katharine Graham calls the strike a “war”. Don Graham speaks about it with a fervid but controlled intensity, describing it as the most concentrated pressure he’s ever been under. “It was hard mentally, emotionally, psychologically. I remember the first day and the last day. The rest is kind of a blur.” During the strike Graham, who had just been named assistant general manager a few weeks before, went to the mattresses, his territory under siege. He slept on his couch inside the office, saw his wife, Mary, about twice the first month, and lost twenty pounds. As head of production, he also got the paper out with a skeleton crew of 125. Though not in a policymaking position, he performed a vital function. To the dismay of many, he seemed to emerge as a much narrower and tougher manager with a less than liberal attitude towards labor. “His attitude is that of a plantation owner,” says a reporter. “’We own you, we built this plant, my grandfather bought this paper on the auction block.’ But he never tells you what his vision of a great newspaper is.” To others, Don Graham’s performance during the strike proved something very different. “After the strike,” says a Post Company executive, “Don no longer simply inherited the paper, he had earned the paper.”

Donald Edward Graham was born in 1945, the year before his father, Philip, onetime law clerk to Felix Frankfurter and considered one of the brightest and most dazzling men of his generation, became publisher of the Post. The paper was losing a million dollars a year. Donnie, who taught himself to read off the Post sports page at age three, has always put newspapers at the center of his life. In 1954 the Post took off by buying out the other morning paper, the bigger Times-Herald. His grandfather reportedly remarked. “The real significance of this event is that it makes the paper safe for Donnie.” By then little Donnie was already in his room writing his own newspaper.

Nobody in the big house in Georgetown where Donnie grew up remembers that he was especially preordained to take over the paper. “He wasn’t one of those Tibetan babies doomed to be the lama fairly off the mark,” protests friend Tim Meyer. Katharine Graham says, “It was a decision that sort of made itself. He was there.” His mother remembers that he was always very conscientious, and today she still finds his degree of concern, his earnestness—qualities shared by his wife, Mary—highly unusual. “They’re the only people I know who actually buy government reports,” says Katharine Graham. She adds there is room for two of her children to work in the family empire. “It’d be great if Bill wanted to come on the paper, but he likes law, and Lally and Steve went a different way.”

Among his siblings Donnie was always the square. His sister says she can’t recall the trip now, but a friend of the family relates the story of a vacation trip the Grahams took—all of them except Donnie. As their small plane flew over the Alps it suddenly hit bad weather and began bouncing up and down. In the middle of the turbulence, Lally turned to her parents. “If this plane crashes and we all die, then that damn Donnie will get all the money,” she said, “and he won’t even know how to enjoy it.”

Whether in high school at St. Albans in Washington, where he was editor of the school paper, or in college, Donnie earned his reputation for being bright, earnest, and the once and future media prince. “Everybody knew he was the heir to a great media fortune,” says a college friend. “He always had to carry so much baggage. There were bound to be jealousies, and others sucked up.” At Harvard, where he majored in English history and literature, he first introduced himself by saying, “Hi, my name’s Graham as in cracker,” but he quickly wised up and emerged as the respected president of the highly charged daily, the Crimson, an elite meritocracy which became the focus of his life. “I don’t remember him being a flashy writer,” says Joe Russin, who oversaw Graham’s induction onto the school daily, “but a good one.”

To test him, Russin and other reporters fed Graham a phony story. (One of them blond and brainy Mary Wissler, daughter of a University of Chicago medical professor, was ironically to become Graham’s wife shortly after graduation.) He refused to fall for it. Then they fed him phony page proofs. “Okay, you guys,” Graham teased. “I’ll buy any damn paper you’re on just for the fun of firing you.” “That’s when I realized here was a guy who was going to have a lot of responsibility,” said Russin. “He was like a good king brought up to realize everything he does would have a moral resonance,” said Faye Levine, another Crimson writer, “and so he knew to be very careful in everything he did.”

During the summer between his freshman and sophomore years, Graham’s father took his first leave from a mental hospital. After years of erratic behavior, his brilliant, witty, and hard-drinking father was being treated for severe manic depression. Suddenly Kay Graham heard a shot. Her husband had committed suicide. The tragedy brought Don Graham one step closer to inheriting the empire. On the day of her husband’s funeral, Katharine Graham stepped forward to ensure that inheritance. She would not sell, she told the Post board of directors. “There is another generation, and we intend to turn it over to them.” Everybody knew whom she was talking about.

“After Phil died I wanted to do what I could as a substitute father,” says Alfred Friendly Sr., Don Graham’s father’s best friend and former longtime managing editor of the Post. “He didn’t come to me.” Friendly thinks the suicide has obviously taken its toll on Graham. “Living through his father’s madness must always be in the back of his mind.” “After his father died he changed,” says Marty Levine. “People will tell you about a wall, a shell—that’s when I first noticed it. He grew up a lot.” “He’s very ambivalent about his father,” says a college friend, “very proud and very embarrassed about his carryings-on. It made people protective of him because he’s a sensitive guy.”

When Graham talks about his father’s death, his voice drops down to a whisper. He admits that of course it affected him, but says with typical obfuscation, “Nobody knows all about how, exactly, we’re affected by such things.” Until recently Don Graham, possibly still haunted by his father’s drinking, barely touched alcohol. These days, Mary, who many think is the best thing that ever happened to him, has gotten him to sip a little wine at dinner.

During those earlier years of the sixties, perhaps under the influence of “Uncle Joe” Alsop and the other gung-ho-Vietnam writers at the Post, Graham stood to the right of many of his peers. Comments from those years in Crimson logbooks portray DEG—Donald E. Graham—as an unremitting apologist for Vietnam: “Hear the forces of evil—DEG—support bombings, poison gas, napalm, despotism…”

By the time Graham graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in June of 1966, Post reporter Murray Marder had already accused Lyndon Johnson of having a “credibility gap.” Walter Lippmann had already written on the Post op-ed page, “We are in deepening trouble because we are too proud to recognize a mistake.” Editorially, however, the Post still favored the war, and Graham followed through on his own similar political convictions: He decided to let himself be drafter. “I did not think that all American troops should be withdrawn from Vietnam in June of ’66,” says Graham, “and I knew that I ought to live my life the way I believed and not seek special privileges.” “Please,” he later told a fellow soldier from Harvard, “don’t tell them who my mother is.”

But as a private in Vietnam, Graham, who had packed Dickens in his duffel bag, was treated more like Prince Charles doing his stint with the Royal Navy. Senator Edward Kennedy visited Vietnam and made a request to see Private Graham. Officers in Graham’s company rehearsed briefings for Uncle Joe Alsop. And Graham’s commanding officer, Major William Whitters, petrified something might happen to his star private, tried to keep him grounded. The major, however, failed: Graham was shot down in a helicopter. But even in Vietnam he found himself involved in journalism—as a flack for the war during the very period chronicled in the Pentagon Papers. As a public-information specialist in the First Air Cavalry, he wrote upbeat stories for army publications and hometown newspapers about the local boys at the front.

“Anyone going into a war wants to believe his country is right,” Graham says of those days, “but you can’t help but react to what’s going on around you and find it stupid and senseless and wrong. I was confused about the war when I went over and confused in a different way when I came back. I still am.” After returning in 1968, Graham was in a position to influence some of the most powerful men in Washington. The Times was against the war, but the Post still clung to its editorial support of the conflict. Yet Don rarely talked about it. “People didn’t ask me,” he says.

During his last three months in Vietnam, Graham was faced with getting a real job for the first time. He now abandoned any lingering questions about his fate in life: He would one day rule the Post. He thought about his father—the responsibility lay deep. “He cared so much. He was publisher when the paper had few resources.”

But the decision was less automatic than might be assumed, even for so dutiful a man as Don Graham. Today Graham’s touchy on the subject, and when he does discuss it, it’s in the third person. “It always occurred to me that one is pulled in two directions. One the one hand, one has a family engaged in a fascinating business and on the other there is a pull to do something exclusively your own.” “Yes, but how did you really feel?” he was pressed. “Ambivalent!” Graham snapped and abruptly left the room.

Graham’s first step in preparing to take over the Post was definitely thought odd even in his mother’s circle—it was simply not the sort of act of noblesse oblige they were used to. Typically, it was also totally out of sync with the rest of his generation. Many of his contemporaries called cops pigs. His younger brother Bill, was turning into a student radical at Stanford. But Don Graham became a cop. “I thought he’d been walking around with a gun long enough,” said his mother. Graham, however, wanted to understand the community he had decided to serve. “I’d been away six years,” he says. “I knew absolutely nothing about the city, and I thought it would be useful to see it from someone else’s point of view.”

As it was, Graham was assigned to the 9th Precinct, an area in the southeast section of Washington. It was 95 percent black and tough. As a cop he often responded to domestic quarrels and became convinced that in the ghetto, alcohol was more dangerous than heroin. And once again he was singled out as special. “Guys were looking for him to do something wrong so they could say, ‘See, he couldn’t cut it.’ I don’t think he was well liked at all,” says Inspector Rodwell Catoe of the D.C. police force, who was Graham’s superior at the time. In the end Graham made friends with a group of young black officers. Catoe thought he always took his work terribly seriously. “It was a turnoff to a lot of people—he didn’t let go at all.” But Graham earned the tough black officer’s respect. “He had an ability to deal interpersonally with people,” Catoe said. “I thought I’d have problems with the community people, but I never got any complaints. He was flexible, and I was convinced he was sincere.”

Graham said he loved being a cop and had he not gone to the Post might still be at police work today. While it’s hard to doubt his sincerity, it’s equally hard to accept such an act of noblesse oblige at face value. Having one of the world’s great media empires at your fingertips is not exactly the usual option for an ambitious young cop on the beat.

Finally, in January 1971, Don Graham, who had been in training for his job all his life, officially joined the Post to being a meticulous eight-year preparation that took him into almost every corner of the empire. It was also the year his mother made the decision to take the Post stock public—among other reasons, to save on future inheritance taxes and, above all, to maintain family control. As the chosen inheritor, Don Graham, of all the children, has the most stock.

Graham’s first job was as a reporter on the “Metro” section. He called upon his police experience and wrote a series on alcoholism. He reviewed cop novels and covered Washington’s May Day riots. Not surprisingly, there most of all, in the Post’s palpably intense newsroom filled with restless talent and edgy egocentrics, his special status separated him from the rest. “I remember everyone bussing,” says Sally Quinn, “’Oh, Christ, here comes the publisher’s son.’ It was clear he’d have to pass some sort of test.” After people had avoided him for a couple of months, Quinn decided to break the ice. “I went up and said, ‘I want you to know people like you.’ He was very pleased; he felt enormously relieved.”

When the Post was going through Watergate, Don Graham was on the sidelines, working for Newsweek. He obviously prefers the editorial to the business side of the paper. Still, he trained obediently, including loading papers at 3 A.M. As the heir he could not afford to dislike any of it—nor will he admit that he did.

By 1978 Graham had long been ready to take over the reigns of the Post. Only his mother stood in his way. “She had the bends for a while,” says Ben Bradlee. “She worried unnecessarily that people would forget her. First she toyed with doing it in early ’78. Finally, last fall I said, ‘When are you going to do it?’ She said, ‘None of your business.’ So I knew she’s made up her mind. It was a bigger deal to her than anyone else. I think Donnie was dying to be publisher but he would have deferred to her for years. It’s not in his nature to rebel.” Last October Kay Graham called her son to her office and said she’s made her decision. He would be paid $90,000 a year. “He asked if I was sure,” said Katharine Graham, “then told me to let him know if I changed my mind.”

To most close observers Don Graham’s working relationship with “Kay” appears formal. “It is not a parent-son relationship,” says Mark Meagher, president of the Post Company and Don Graham’s boss. “They act like two people who aren’t related. It’s a business relationship. I’ve never seen any emotion flash between them.” One Newsweek editor was surprised to watch Don Graham arrive at his mother’s New York office, lean across the desk, and formally shake hands with her. “It’s tougher to be the son than the mother,” Katharine Graham says. “Both of us have a lot of respect for the other, and we make our relationship as close to a regular business relationship as we both want to. It is and it isn’t.” Graham himself refuses to speculate on how he’ll establish an identity for himself at the Post. “The uniqueness of my mother’s story is that she had something dropped in her lap. She had to fill in without warning, and she performed brilliantly. We aren’t much the same.”

The question remains, however, what exactly will Don Graham do with the Washington Post—except go to the bank? Judging from his past, it is unlikely Graham, who is known to have a strong commitment to both affirmative-action programs and local news, will undermine the liberal-establishment image the Posthas carved out for itself over the years—any more than it’s already been undermined by the strike. As a registered independent, Graham could pass for trendy Jerry Brown when he defines himself politically as “curious, eclectic, and open. I’ll take the pragmatic approach,” he says characteristically. “I have a sense of growing up in the fifties, sixties, and seventies, of how many times the conventional wisdom and sense have led to the wrong conclusion. We are going over every aspect of the paper and seeing how we can do it better. The changes will be gradual and evolutionary.”

As the new king, Graham, courteous and diffident as ever, is still playing it very close to the vest. Ben Bradlee, who offered to resign when Graham took over, can stay as long as he wants although he is known to be restless and asks rhetorically, “How long, oh Lord, how long?” It does appear that veterans like Dick Harwood, 54, and Howard Simons, 50, who might have thought they’d get first crack at Bradlee’s job, are being passed over as Graham grooms a host of younger hopefuls, new “Metro” editor Bob Woodward and London correspondent Leonard Downie chief among them. According to Katharine Graham, however, they are not the only candidates. “You have to bring up a lot of young editors: Shelby Coffey [“Style” editor], George Solomon [“Sports” editor], Peter Osnon [a foreign editor]—they’re all good.” Graham, of course, has no comment. In fact, shortly before his mother recently fired Ed Kosner as editor of Newsweek he gave Kosner a ringing endorsement. Later he laughed off his remarks, saying, “That just goes to show you how out of touch I am with the rest of the empire.” Sure. Then in the next breath he wanted to know what people were saying about it.

Graham’s most immediate challenge is the Star, and he has been holding a series of in-house lunches to solicit suggestions about it. Two months ago the Star brazenly stole the Post’s most popular comic strip, Doonesbury, so nonplussing Bradlee that he called the Star “the biggest challenge since Nixon.” In fact, the newly flush and aggressive Star has begun to sell morning editions on the newsstand in direct competition with the Post, has brought out zoned editions for the suburbs, and is gaining slightly in circulation. At 340,000 daily it’s up 20,000 since Time took over.

To meet the challenge, Graham is going over every section of the paper. This year, for example, the Post has hired a number of outstanding reporters: Marty Schram from Newsday to cover the White House, sportswriter Tony Kornheiser from the Times to write for “Style”, and Jonathan Neuman, Pulitzer Prize winner from the Philadelphia Enquirer. There are several new editors, a new “Style Plus” page, a Sunday food edition, and extended weather package, a new reporter in San Francisco, new bureaus in New Delhi and West Africa, and a Sunday tabloid book review. Next to come—an expanded TV magazine.

The major change since he became publisher, indeed the only surprise, was the firing of Phil Geyelin, the longtime and respected editorial-page editor. He was replaced by his equally respected deputy, Meg Greenfield. Graham did the actual firing, but it’s understood both he and his mother did not feel Geyelin had been producing first-class work. Their hand was forced prematurely, however, when word leaked to the Star and New York Times. The Post, in order to avoid being scooped, had to issue a clumsy announcement about Geyelin taking a sabbatical. But one must wonder whether the decision to fire Geyelin, the only editor except Bradlee who reported directly to the publisher, was initiated by Donald or his mother.

Meg Greenfield says that by 1980 the intensely political but usually non-partisan Post will begin to endorse both local and national political candidates on a regular basis, but Graham denies it. “I’m still ambivalent about that,” he says. Greenfield’s appointment, however, is not likely to change the Post’s basic editorial policy: strong commitment to civil liberties, support of SALT, and support of nuclear energy—if, Greenfield adds, “it can be made safe.”

The Post has been dubbed “the number-two source of power in Washington.” In assessing its future with Don Graham as publisher, it’s as difficult to forget his confusion over Vietnam—a confusion he still has today—as it is easy to realize how his pragmatic, issue-by-issue approach fits in with the current trend of declining party loyalty. But if he does have a vision for the Post, he isn’t telling how he wants to exercise his considerable power. The newly crowned ruler is ever orderly and obedient in the transition. “I don’t feel any compulsion to put my own stamp on the paper,” he says. “I feel it’s basically on the right track but that we can do better.”

It is not even that easy to assess Don Graham among the other bright young men in Washington today. “How can you?” says a friend who fits in that category. “His major struggle was over before he was born. Donnie has never had to develop the skills most men who aim for his position do—the manipulation, the infighting, the reliance on gut reaction that someone like Hamilton Jordan has. He started where everybody else wants to end up.”

Perhaps Ben Bradlee puts it best. “Donnie can do anything he wants,” cries Bradlee, leaping up from his desk. “He’s got the A stock.” He pauses to let the power of the empire sink in. “The A-hyphen stock!”

The $500-Million Empire

The Washington Post is not just one of the most powerful newspapers in the country; it is also one of the richest. Must reading for thousands in and out of government, the Post has the advantage of publishing in recession-proof Washington, where it dominates the market as does almost no other daily in a major city. While the New York Times reaches only an elite 11 percent of New York households, the Post—circulation 600,000 daily, 822,000 Sundays—penetrates 47 percent of all Washington households (62 percent Sundays). Most important, the Post publishes 72 percent of all newspaper advertising in the Washington area. Next year, the Post will open a new $60-million printing plant in Fairfax County, Virginia, giving it the capacity to print another 200,000 papers daily.

Such dominance is one reason the Post, with sales of approximately $213 million, was the highest-grossing arm of the Washington Post Company, which also owns Newsweek, the Trenton (New Jersey) Times, the Everett (Washington) Herald, four TV stations, a book division, and is about to launch a new sports magazine, Inside Sports. Gross sales from those enterprises totaled $520 million in 1978. For all its wealth, the corporation is a very closely held, conservatively run media empire very much under the Graham’s control, with the family voting nine of the Post’s thirteen directors. Katharine Graham alone votes 50.1 percent of the Class A stock. The four children and a trustee vote the remainder, with Donald Graham, an heir and publisher, having the largest block, 12.6 percent. –M.O.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.