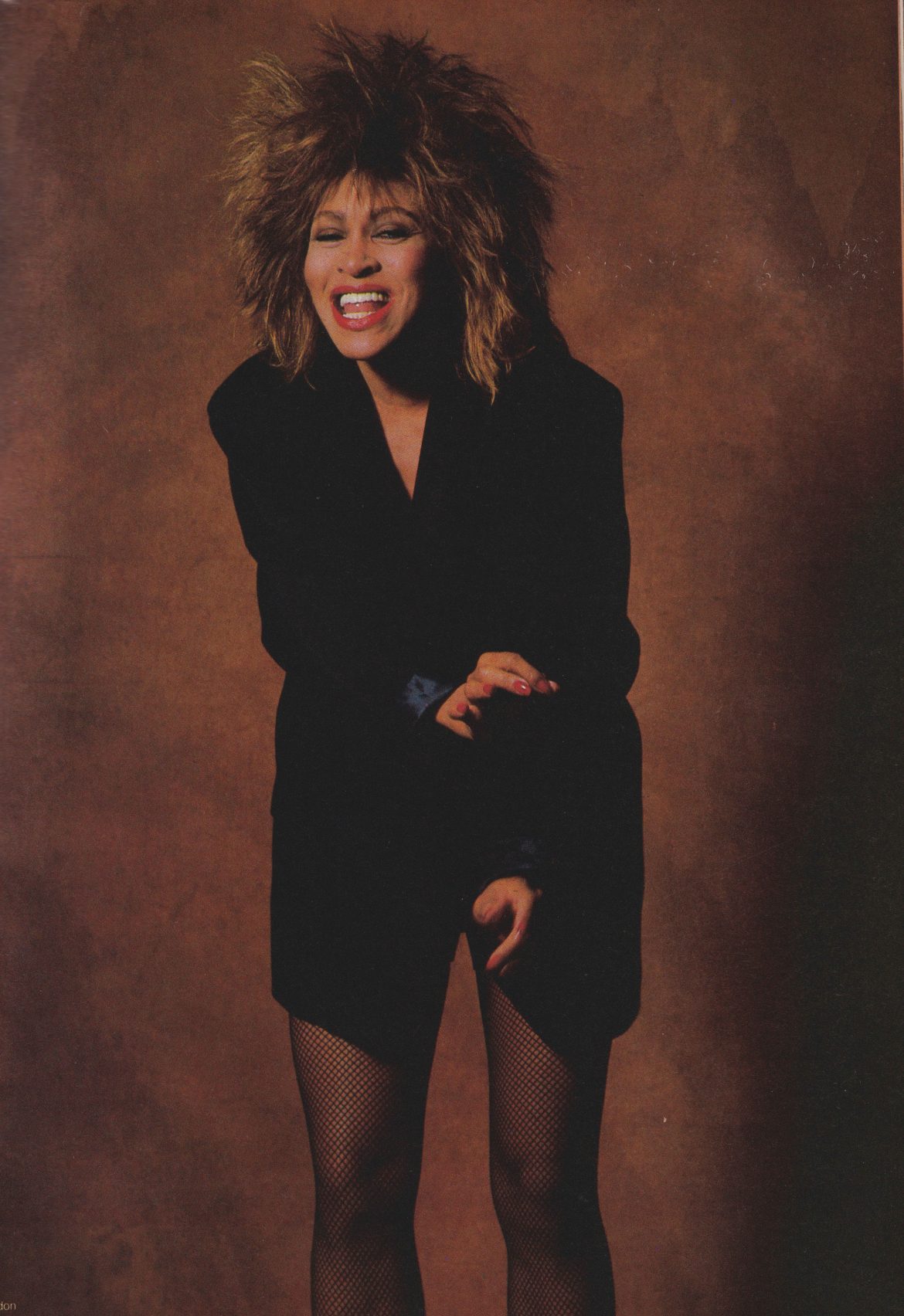

Tina Turner, swathed in full-length black mink, is riding in the back of a limousine to a rehearsal of Saturday Night Live. With her are her tall, blond Australian manager, Roger Davies, and her dresser, Teamer Washington. Preceding her is another limo carrying several trunks of her designer dresses and her royal-blue metal makeup case, about the size of a coffee table. She retired the night before at 7:00 P.M., having resolved to tell director Steven Spielberg that she wasn’t interested in a leading role in the important new film, the screen adaptation of Alice Walker’s novel, The Color Purple. Tina Turner felt it was too dark a tale for her newfound happiness.

“The part’s too old – she’s been with every man in town and this man brings her into his house with his wife. No. I know this already from my past,” Tina Turner says. “I want to do a Raiders or a Western next. There is no way I’m a drag right now.”

No way at all. Turner, known once as “the queen of raunch and roll” and as the wife of her musical partner Ike Turner, has survived being a battered wife and an over-the-hill ‘sixties rock star, as well as a divorce that left her penniless. A few years ago, her career was in ruins, and she was forced to trade on her legend by playing tacky lounges or appearing in remote parts of the world. Today, fueled by her electrifying performances, which lend themselves so well to MTV, she has been discovered all over again as the hottest female singer in the country.

On stage, Turner seethes sexuality –she screams, she sweats, she kicks up her famous stiletto-heeled legs, and in a sinuous growl halfway to a roar, she belts out the hits from her LP Private Dancer. Released last year, Private Dancer has sold over six million copies, spawned four hit singles, and has won her three Grammys. It’s been printed that William Morrow Publishers paid $440,000 for Turner’s life story. This month, she appears in an HBO in-concert special. In July, she’s featured onscreen with Mel Gibson in the third Road Warrior movie, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Later in the summer, she is scheduled to record a new album, then will complete the year touring the United States and Southeast Asia. In pop music, Turner’s is the comeback of the decade. Yet certain little things can still be a drag.

Glancing out onto Park Avenue through the hazed limousine window, Tina Turner tugs on her electrified-looking, streaked blond hair, then shakes a delicately manicured finger. “Mick Jagger, I’m not that much older than you!” She is referring to a comment she heard Jagger make on MTV that he used to watch her as a teenager and also copied some of her onstage moves. “I started out on the road so young, people think I’m ancient. There’s only four years difference between me and Mick. ”

Tina Turner admits to forty-five, well maybe forty-six.

But some people say she’s sixty. “There’s no way a sixty-year-old woman can look the way I look.” People are even rude enough to ask her point blank whether she’s gone through menopause. The answer is no.

In fact, Tina, the mother of two sons aged twenty-four and twenty-six, explains that a few years ago she wanted a little girl so much she took to walking around airports with a life-sized baby doll she bought in Spain. “She was the same color as me and looked so real. Then what happened to her, Roger?” she asks her manager.

“We put her in the trunk.”

“Right. One day I just said, ‘She goes in the trunk.’ ”

Fifteen years ago, Turner would drive young men wild by leaning back, planting her micro-minied legs firmly apart, and practically shoving the microphone down her throat before raucously rasping the introduction to “Proud Mary”:

“We nevah, evah, do anything nice and easy. We always do it nice and rough!”

Today she has a softer sounding, younger band (only her keyboard player is black); and the famous “Ikettes;’ her campy, choreographed back-up singers, are banished forever. Today, Tina says, it’s just “me and my boys.”

“What’s love got to do, got to do with it?” she coos at her Saturday Night Live rehearsal, handling the microphone like a snake charmer. Even at a sound check, she gives as much of herself as when she’s onstage for real. The bleachers are packed with cast and crew alike, all gawking at her sensational body. “No white woman can move like Tina Turner,” sighs someone in the crowd. By show time, two famous wives — actresses Jamie Lee Curtis, married to SNL regular Christopher Guest, and Susan St. James, married to executive producer Dick Ebersol — are joined in the front row by Faye Dunaway. The three women stars sit there mesmerized by Tina Turner, who is undulating in spike heels and black leather.

Her manager says she can go straight to bed after a performance that has left thousands screaming in the aisles and be asleep within one hour. A devout Buddhist, a believer in reincarnation — she is convinced she was once a Parisian dance hall girl and an Egyptian queen — Tina maintains her equilibrium by chanting every day and keeps a close eye on her future by consulting numerous readers and psychics. “I want to see the movie of my life, so I get psychics to see it for me.” Says her manager, Davies, “I can’t believe it. She just had her auras cleaned again!”

In this life, Tina Turner looks about thirty-six, and her skin is flawless. She does not deprive herself. She sips wine at dinner, does not diet, does not take vitamins. If she’s feeling particularly stressed, she consults a homeopathic doctor in London who gives her intravenous treatments “to cleanse the toxins from the blood.” The next day, he replenishes her with special vitamins and mineral supplements supplied via intravenous drips. Twenty-seven or so years of non-stop motion onstage, in five-inch heels no less, and walking for miles in airports have left Tina Turner with the figure she had at eighteen. “If I wasn’t in shape after all that, there’d be something wrong,” she says. As for those incredible legs, “They’ve stayed the same. I think I just came out singing and dancing.”

Tina Turner “came out” Anna Mae Bullock on a cotton plantation, in Nutbush, Tennessee, where her father was the major domo. She remembers her rural childhood fondly — riding bareback, fantasizing herself a cowgirl in westerns, and singing after school in the fields while picking crops. In high school in St. Louis, where she moved with her mother after her parents divorced, she was known as “Little Ann.” “Black women were very heavy in those days with big hips and things,” says Tina. “And I was very small, so I was ‘Little Ann.’ When my career started, Ike thought we had to get a name with a sound for the stage. He had a thing for the women in movies who swing on the vines–the jungle queens. ” One assumes “Tina” reminded him of “Sheena.”

Ann Bullock had met the Mississippi-born Izear Luster Turner as a teenager in 1956 when she went to a St. Louis rhythm and blues club where he was performing. He was married at the time and in 1951 had produced Rocket 88, which is widely considered the very first rock and roll record. One night at the club, Little Ann grabbed the microphone and startled everyone with her singing. Soon she began to sing on a regular basis with Ike’s “Kings of Rhythm,” and became pregnant with her first son by one of the band members. The father later returned to Mississippi. By the time” A Fool in Love,” the first hit single by “Ike and Tina Turner,” started climbing the charts in 1960, she was in the hospital, jaundiced, and pregnant with Ike’s child, though they didn’t marry for several years. Still sick, she crawled out of her hospital bed to go on the road to promote the record.

Ike always saw to it that Ann, as he called her, had beautiful clothes and fancy cars to ride around in. But the rise of Ike and Tina Turner to superstar status during the Woodstock years was always shadowed by whispered tales of Ike’s treatment of Tina. Even today, in his performances, Little Richard refers to his witnessing Ike beating Tina. There were stories, too, about Ike’s harem of Ikettes and thinly veiled references to drugs and guns. Still, Tina stayed with Ike for almost twenty years.

“I couldn’t leave him because I cared, so I endured it,” she says today. “But I always knew, ‘It’s not me, it’s not my life.’ He was like a brother to me. I thought that if I walk out, everything is lost.” (A psychic once told her, however, that she would leave Ike one day and be successful on her own.)

Tina finally decided to take the risk of losing everything in the middle of a tour in Texas in 1976. She sneaked away from Ike with nothing but thirty-six cents and a Mobil credit card. “What made me leave was the beating,” Tina says. “I thought, ‘I’m not going to be dragged down in the dirt one more time.’ I’m about harmony and happiness. 1 stayed because there was part of me that cared – but finally that can be abused.”

Two weeks later, Ike sent Tina her clothes, which was all she wanted despite the wealth they had accumulated together. He tried to continue on the tour on his own without warning local bookers he was without Tina. When they found out, they sued them both for breach of contract. Tina went into seclusion. On one occasion, a gun was reportedly shot into the home where she was thought to be staying. She was undeterred. Today, Tina no longer accepts Ike Turner’s phone calls “because it’s too sad.”

“I’m not ashamed of it,” Tina Turner says about the fact that she lived on food stamps after she left Ike. She rented a little house in Coldwater Canyon in Beverly Hills, bought cookware with green stamps she had saved, and rented furniture from Abbey Rents. “It was like playing house.” To earn money she started appearing on Canadian TV variety shows and The Hollywood Squares, “After I left Ike, I had my dream to find a rich man to protect me and take care of me. I haven’t found him yet.”

When she started working again in small cabarets, Tina was unused to managing herself and a band, and hired poor advisors. She owed bills and got slapped for back taxes.

“Roger had me get rid of everybody,” says Tina of her manager, Roger Davies, who started working with her in 1979. She fired her longtime band and threw away her chiffon and feathers. Davies started booking her into rock clubs to expose her to younger audiences. Her first big break came when the Rolling Stones asked her to tour with them in 1981. Then Rod Stewart had her appear on his TV special. Even so, Tina Turner could not get a record deal. Says Davies, “There was a terrible stigma attached to her because she walked out on the tour and because everybody still thought she was with Ike.”

Finally, Europe gave Turner her salvation. “We more or less survived off of Poland, Hungary, Yugoslavia, even Teheran — places like that,” Davies says. In 1982, an English band, Heaven 17, asked Tina to record an old Temptations’ song for an album and a video they were doing, and she became the first black female to appear on MTV.

Tina finally got a record deal from Capitol in 1982, but, a year later, there was still no album. Then, her version of Al Green’s “Lets Stay Together” — a top-five single in Europe — became the most-requested dance tune in New York. Capitol Records was astounded.

Roger Davies was desperate not to lose their momentum. “I hit the streets,” he says. “I called everyone I knew and begged for songs.” When Tina first heard “What’s Love Got To Do With It,” her Grammy-winning song, she hated it. “I can’t sing this wimpy crap,” Davies recalls her saying. A few chord changes helped change her mind, and Turner recorded her first album in almost a decade. The New York Times pronounced it a “landmark” in the “evolution of pop-soul music.” More importantly, it started to sell, and suddenly the woman who was dubbed a few years before “the Mae West of rock and roll” had a brand-new career.

“I’m going through being a girl again,” Tina announces today. As Private Dancer soared up the charts so has Tina Turner’s exuberance. A compulsive shopper — “that’s my vice” — she has indulged in fine things for herself and her house in Los Angeles, where she retreats after tours and where she may not answer the phone for a week. But it’s clear she never wants the music to stop. “She was so unhappy torso long, she can’t stand it to get too dark;” says Davies. “She hates people feeling sorry for her.”

Sometimes it’s hard not to. “Every relationship is a bad one,” she says of her love life so far. “I have not had love from a man.”

Perhaps that is why Tina refuses to assume the responsibility of becoming any sort of spokesperson for the other abused women. “I’m not finished educating myself yet to be able to explain it totally. I figure I’ve got a good seven years left of being onstage with the physical thing. When that’s over I’ll put my attention to teaching. ”

Teaching what exactly?

“Living without blame. That is the secret to life. People think I’m bitter or that I hold a grudge against my ex-husband. I’m not bitter. I had a road and I followed it.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.