Original Publication – Doug – September, 1985

Martin Scorsese has given us some of the most aggressively unlikable but powerful screen protagonists of the last decade. From Travis Bickle, the psychotic Taxi Driver who John Hinkley says inspired him to try to assassinate President Reagan, to Jake LaMotta, the self-destructive ex-middleweight champ of Raging Bull,Scorsese, teamed with his favorite actor, Robert De Niro, creates a horrifying and lurid universe – but one that we can’t stop watching.

The world according to Scorsese is filled with evil, temptation, menace, and sometimes paranoid humor, all drenched in operatic intensity. He first stunned audiences in 1973 with Mean Streets, the gritty portrait of the Little Italy neighborhood in New York City where he grew up. His last film, the brilliant King of Comedy, cast De Niro as a deranged fan, desperate for fame, who kidnaps a TV talk-show host.

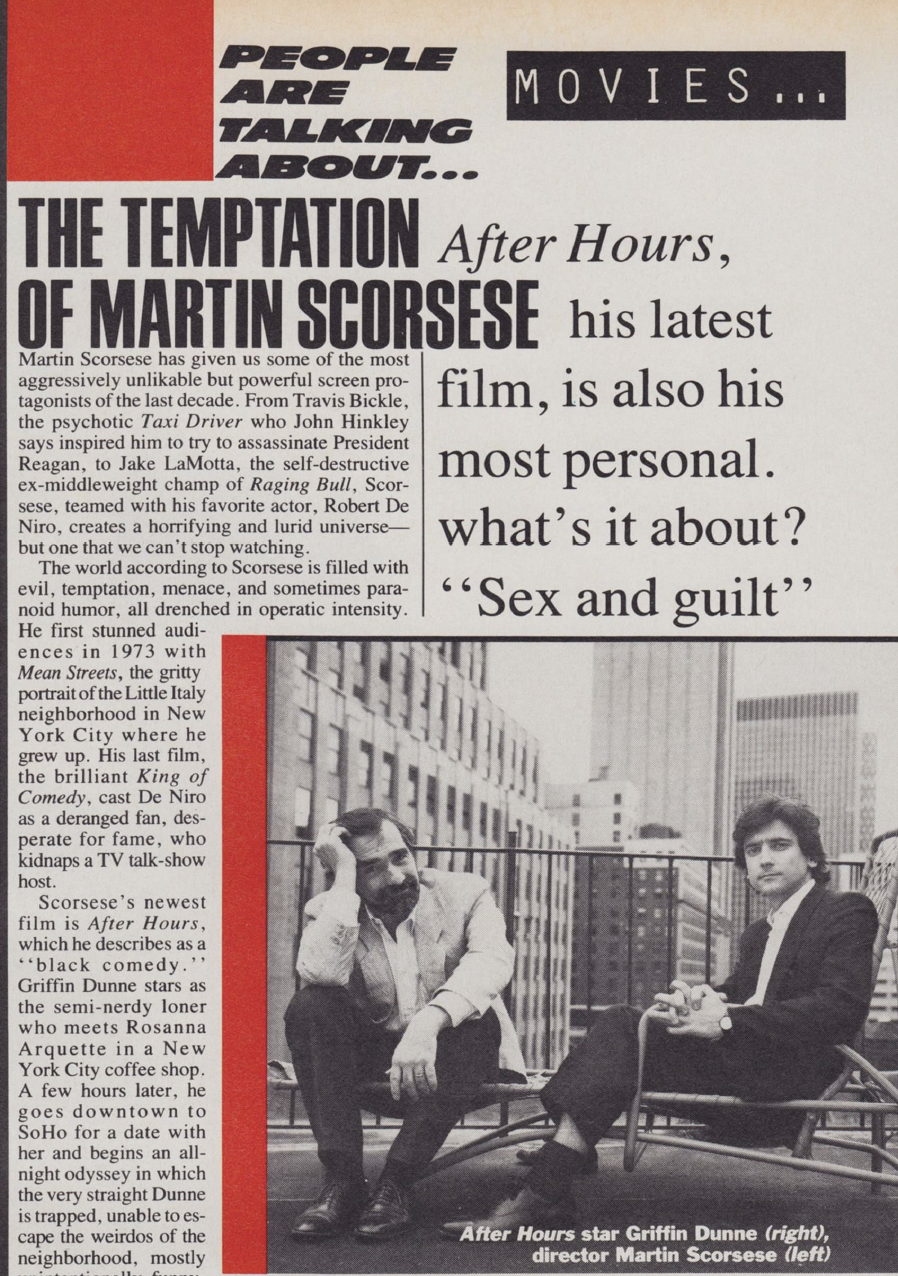

Scorsese’s newest film is After Hours, which he describes as a “black comedy.” Griffin Dunne stars as the semi-nerdy loner who meets Rosanna Arquette in a New York City coffee shop. A few hours later, he goes downtown to SoHo for a date with her and begins an all-night odyssey in which the very straight Dunne is trapped, unable to escape the weirdos of the neighborhood, mostly unintentionally funny, neurotic women. All his money is gone and his life is in danger. Not surprisingly, Scorsese didn’t much care if Dunne escaped the nightmare. Others, however, persuaded him to reshoot a new, “happy” ending. In the editing room, Scorsese says, he discovered that After Hours is one of the most personal films he has made.

“It’s not just about weird neurotic girls,” he says, “it’s about sex and guilt.” “But there’s no sex in the film,” I point out. “Of course not. That’s the beauty of it,” Scorsese answers. “But they all feel guilty. He feels guilty.”

Despite four marriages and despite highly praised films in which unrepentant sinners always outnumber saints, Martin Scorsese at forty-two remains a captive of his strict Catholic upbringing, one in which sex and guilt are intertwined. At one point in his youth, he even studied for the priesthood but was kicked out for poor grades. He says he was obsessed by girls, and during meditation images of women’s ankles would pop into his brain. “Then you’re doubly in trouble with the guilt. It’s the old concept of mortal sin: you’re in the wrong if you’re tempted. And if you give in it’s a mortal sin. That’s what they taught us, right?”

Scorsese seems as self-absorbed as haunted. “It’s really a self-examination I’m trying to do, and the only way I know how to do it is on film. I seem to be trying to analyze the negative. It’s dangerous. The people around you may not survive, relationships may break up, but maybe you remain alive . . . In a sense it gets down to a very religious idea, which is salvation. How do we redeem ourselves?”

Interestingly, Federico Fellini, one of Scorsese’s heroes, portrays himself in Amarcord as the little boy who bounded out of bed to gaze upon the magic of the circus tent unfolding beneath his window. Scorsese, however, spent much of his asthmatic childhood cramped into a tiny apartment watching the violence of the street. Always catered to by doting parents, little Marty would often watch old movies on TV, listen to the radio, and sketch tiny drawings, storyboards of his first “movies.” He still frequently isolates himself in bed or in his trailer on the movie set. His mother still brings him homemade pasta for dinner, and he still uses the same tiny drawings to plot all of his shots. “He breakfasts off images,” British director Michael Powell has written, “eats tapes for lunch, and comes surfing over sound waves to dinner.”

Scorsese is a key member of the original “movie brat” generation of directors – Francis Coppola, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg. All but Lucas went through periods of wretched excess – making movies that went way over budget and then bombed at the box office. Scorsese’s failure was nonetheless interesting, his 1977 homage to ‘forties and ‘fifties musicals, New York, New York, starring De Niro and Liza Minnelli. Today, studios are much more cautious. After Hours cost under $4 million and was made after Scorsese’s two-year effort to film Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel The Last Temptation of Christ (with a $14 million-plus budget) was suddenly canceled a month before shooting. “If you want to do something unique today,” says Scorsese, “you have to do it cheaply.”

There was a time when fame came so fast and furiously that Scorsese seemed hell-bent on self-destruction. His second marriage broke up, he had a relationship with Liza Minnelli, he married model Isabella Rossellini, and eventually divorced. Friends feared he might end up like John Belushi. “I think at a certain point you reach the limit, and the next thing is either total – death – or you decide to go on. You have to get to that point to know what you really want to do.”

Now, Scorsese is as healthy as he has ever been. He has recently remarried, and his goals are clear: “To do some really good work, to lead a good life according to Christian values, and to find out the way life is supposed to be led.”

But up there on the screen, original sin will probably still linger.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments