Original Publication: New York Woman – July/August 1987

When the rich want out they bring Julia Perles in. Of course, it is understood that before the grande dame of divorce lawyers will even receive a new client– and begin the billing at $300 an hour– the client’s check for $10,000 must already have cleared. That simple house-keeping detail aside, Perles will grant an initial two-hour interview seated in an overstuffed tangerine velvet armchair. At her side is a buzzer used to send minions scurrying to locate obscure passages of legal precedent, which she recalls with prodigious memory. The client quickly senses that this is a face best not lied to. That teensy indiscretion with the D’Agostino delivery boy that will cost you your share of the country house? Cough it right up. That secret equity account you don’t think your wife could possibly know a thing about? Don’t hold back. Nothing should ever surprise Julia Perles. And little does.

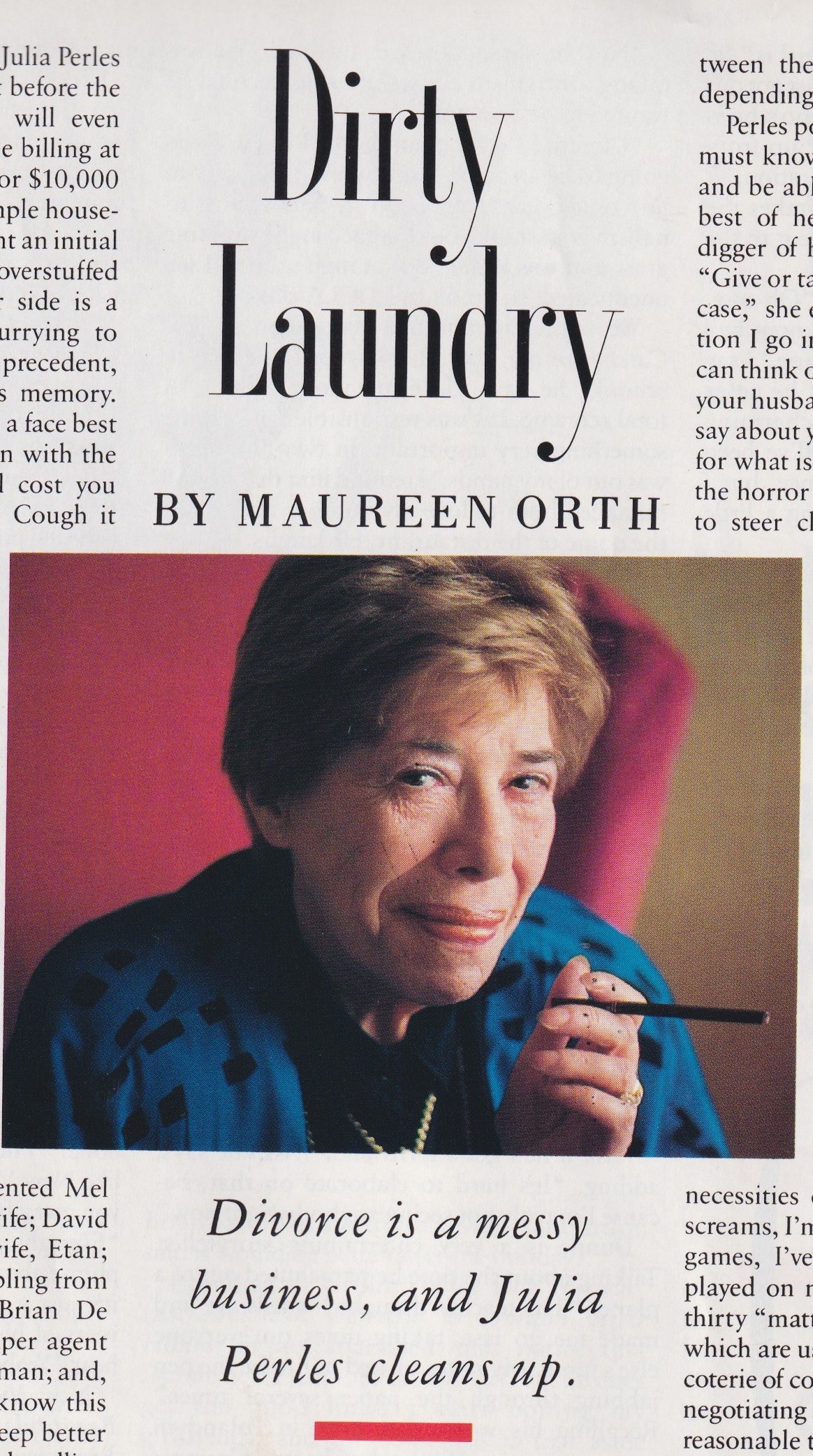

At 73, the Brooklyn-bred “Depression kid” who has fought her way up to the thirty-second floor of 40 West 57th Street to become head of the seven-person matrimonial department at the famed firm of Phillips, Nizer, Benjamin, Krim & Ballon, can size up and shake down the most inveterate fabricator in about two seconds flat. Puffing away on long dark cigarettes, Perles proclaims, “I always say, ‘Get ‘em when they’re guilty.’ This whole thing is about leverage.”

Over the years Perles has represented Mel Brooks in his divorce from his first wife; David Merrick in a suit with his third wife, Etan; Marguax Hemingway in her uncoupling from hamburger king Erroll Wetson; Brian De Palma’s ex, actress Nancy Allen; super agent Lynn Nesbit’s husband, Richard Gilman; and currently, author Nancy Friday. “I know this sounds corny,” says Friday, “but I sleep better every night because I know Julia is handling my case.” She doesn’t win them all of course– Perles is presently awaiting a trial date in malpractice suit brought by pop-art collector Ethel Scull, who contends Perles mishandled her divorce from taxi fleet owner Robert Scull and lost her share of the Scull’s $10 million art collection.

“She’s the most ungrateful client I ever had,” says Perles, who explains that Scull finally won back her property on an appeal based on Perles’s trial record, not the appeal brief. “That divorce was filed before we had equitable distribution.”

Perles, in fact, the godmother of the reform of the 1980 New York state divorce law that produced the doctrine of equitable distribution. Equitable distribution holds that marriage is an economic as well as a social partnership and that property acquired during the course of the marriage does not automatically belong to whoever holds title to it– rather, social and emotional contributions (such as those of a spouse, mother, or wage-earner) must also be counted.

But Perles says that her twenty-year fight to reform that the state divorce law is still far from over. “The current law says assets should be valued between the time of the commencement of a divorce action and the date of the trial. When you are talking about businesses, there are all kinds of hanky panky people can do before an action is started or while it is pending. We think that the court should have discretion to choose any valuation date between the date of marriage and the trial, depending on the circumstances of the case.”

Perles points out that a good divorce lawyer must know corporate law, trusts and estates, and be able to read a balance sheet. Like the best of her breed, Perles is both practiced digger of hidden assets and killer negotiator. “Give or take a few zeroes, it’s the same in every case,” she explains, “Before I go into negotiation I go into every aspect [of the marriage] I can think of. If it’s a woman coming in, I say, ‘If your husband were sitting here, what would he say about you?’ The answers are very revealing for what is said and what is not said.” Despite the horror stories she often hears, Perles tries to steer clear of becoming emotionally involved with her clients’ problems. “You wouldn’t want a neurosurgeon to feel subjective about your body, would you?” she asks.

Although Perles wears designer clothes, carries a crocodile briefcase, and has a collection of over five hundred owls, she still speaks a raspy Brooklynese and is known to be very tough to go up against. “Julia can be hard as nails. There is no getting by her,” says Louis Nizer, the famous senior partner of Perles firm and bestselling author. “She won’t ever admit her clients are other than right,” says fellow matrimonial attorney and friend, Eleanor Alter. Responds Perles, “I compare myself to a broken-field runner. I adapt my style to the necessities of the situation. If the other guy screams, I’m quiet. If he wants to fight, to play games, I’ve played them all and had them played on me.” At any given time Perles has thirty “matters,” as she calls them, before her, which are usually in play with small, regular coterie of colleagues. By the time she’s through negotiating a settlement, depending on how reasonable the other side is, of course, the vast majority of clients will settle for a 60-40 split of the assets, if they agree on the valuation of the assets. If. “For 50-50,” asserts Perles, “you go to court, you fight.”

In pure mathematical terms, even a civilized upper-middle-class New York divorce today carries a minimum price tag of $15,000 and six figure fees are not uncommon. In fact, Nizer says he has seen “divisions of property worth millions break down over a lamp.” He adds, ‘When love turns to hate, it’s quite a chemical.” Understandable, this is not a profession for wallflowers, and both in court and out, Perles number one nemesis is New York’s flamboyant Raoul Lionel Felder. Felder’s firm took Ethel Scull’s case after Scull fired Perles. “Julia not only lost the case, she sent Ethel a whopping bill besides,” Felder says. Perles and Felder have drawn swords many times in the last fifteen years– there was even a recent period lasting six years during which they did not deign to speak to one another, making negotiations rather uncomfortable at times. Today Fedler refers to Perles’s “juggernaut quality” and sums her up, “She’s a tough old bird. She’s hard to chew.”

Easy to disgust or not, one thing is sure: Julia Perles came up the hard way. Growing up in Brooklyn’s Borough Park, Perles decided as a little girl that she wanted to be an attorney. But when she told her father, a caterer, he said, “Ridiculous! Girls can’t be lawyers. Who would want to go to a girl lawyer?”

Perles had ample occasion to ask herself the same question. After her graduation from Brooklyn Law School and her admittance to the New York state bar in 1939, she left eight jobs before landing at Schwartz and Frohlich, a smallish firm, in 1942. She was one of the first women they ever hired– she was available, and many men were off at war. Perles says she was happy there for ten years but also felt discrimination from the firm’s senior partner. “He finally ordered the partners not to give me any work,” Perles says, “but I ignored him and went merrily on my way. They were paying me well. They were letting me take on personal clients and keep all the fees, which was very unusual.” To teach her “objectivity,” the senior partner ordered Perles to take on her first divorce case after Perles expressed a loathing for the client. She won. “It taught me a very valuable lesson,” she says now.

No matter what was going on at the office, Perles has always made a point to have fun at home. In 1950, she met Howard Singer, a liquor dealer, and married him the next year at the age of thirty-seven. Singer, now ill and in his eighties, never minded that she made more money than he, never objected that most of her friends were male lawyers, and usually greeted her at the door of their Sutton Place apartment at night with dinner already prepared and a waiting martini. There was always a lot to discuss. In 1952, Perles set up shop with Al Julien, keeping her usual long hours and bringing in business but getting little in return. “I was with him for a year and a half. The only trouble was I was his partner in all the junk; he reserved the lucrative area for himself.” So in 1955 when well-known attorney Harriet Pilpel called (“out-of-nowhere,” says Perles) to ask Perles to join– for less money– the prominent firm of Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst, she agreed. Perles stayed there until 1970, developing a specialty in matrimonial law. “I didn’t choose it, it chose me,” she says. “What happens, I think, in any specialty of the law is that somebody decides you’re good at it, and then you get one case after another.” She continued to practice other types of law as well, and it wasn’t until 1967, when she was being considered for a family court judgeship, that Perles was made partner at Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst– having five men promoted ahead of her. Perles was fifty-three years old and graduated law school thirty years before. “Of course it wrankled,” she says today. But she refuses to label what happened to her as sex discrimination: “It was for other reasons, political reasons in the firm.”

“Look, I feel I had a rotten education,” she explains. “Brooklyn Law was not then what it is now. At first I didn’t know how to behave or think like a lawyer. I learned on the job. I was beautifully trained at Schwartz and Frohlich. I think I might have gotten to where I am today ten years earlier if I had been a man.” Today Perles refuses to join the Women’s Bar Association though she says she contributes to it anonymously. Instead, she chairs the New York State Bar Association Equitable Distribution Committee and sits on the editorial board of The Advocate, the magazine published by the family law section of the American Bar Association. “I don’t want to be identified as a woman lawyer. I’m a lawyer. In this day and age, you’re either a professional or you’re not,” she says.

Phillips, Nizer recognized this professionalism in 1970 and offered Perles a partnership in their matrimonial department. Her husband counseled her against the move. Not only was it highly unusual to quit an established firm tens years after, but Howard Singer feared that Perles’s performance would be under unfair scrutiny. “He said, ‘You’ll have to prove yourself all over again’,” she recalls. “That did it. I said to him then, ‘I have to prove myself everyday.”

It was only then, at age 56, that she began to practice matrimonial law exclusively. “She has basically survived in a man’s profession,” says Raoul Lionel Felder. “Most women practicing today could not do what Julia did– work her way from the ground up. She represents the older style of woman lawyer where only the purest of gold panned out.” Felder of course is shrewd enough to know such an endorsement will not make it any easier for him to go up against Perles in the future nor does she show any signs of winding down. She has the satisfaction of seeing many of her cases cited as legal precedent in law journals. She currently bills between 1,200 and 1,300 hours a year and does another 700 hours of administrative work for the firm. Two major surgeries have not felled her, and her memory astounds the youngsters of the firm. Taking a long drag on her cigarette, Perles asks, “Why should I retire? I’m good at what I do. I have fun, and I love the money.”

At $300 an hour, there’s a lot to love.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.