Original Publication – Domino Preview Issue 1987

Sometimes it takes Prince Charming and Oscar de la Renta to make a fairy tale come true

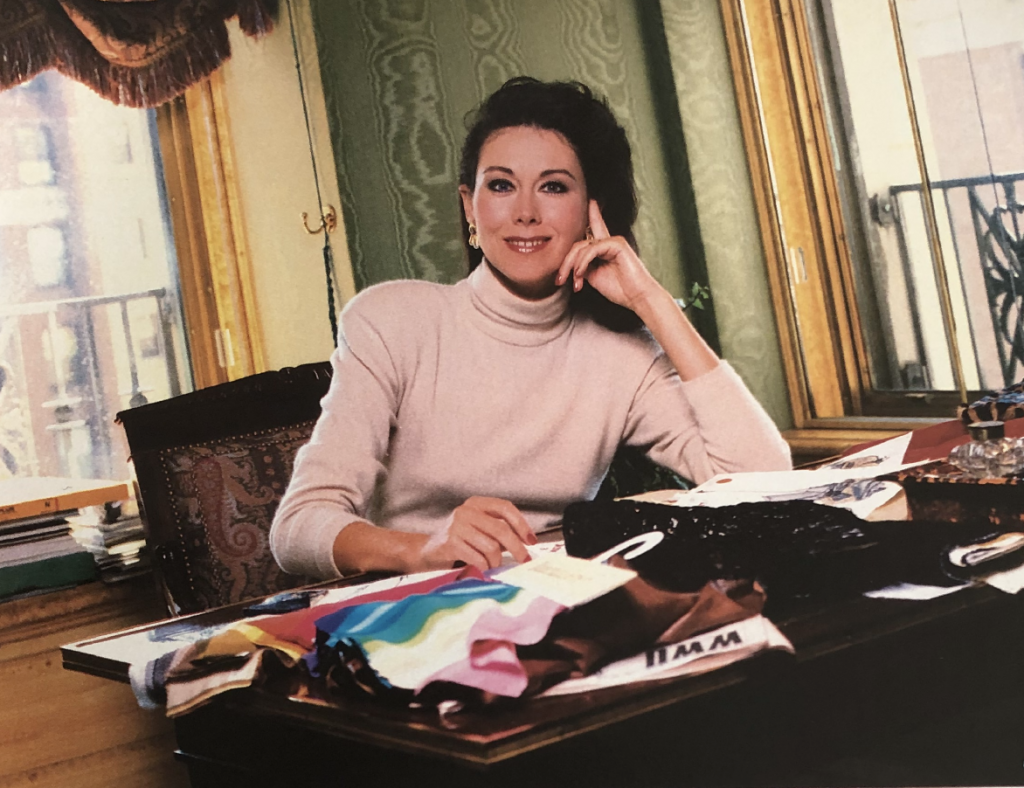

Wearing one of her own slinky creations, Carolyne Roehm is draped across her sofa like a long-stemmed red rose, sparkling and flashing the famous photographer a 20-carat smile. That is about 30 carats less than she is wearing in diamonds. Surrounding her on the walls of the opulent living room of her Park Avenue apartment are no less than nine paintings by Manet, Monet and Renoir. In the dining room there is a major Sargent; Sisley is upstairs and Gainsborough is on the way. In fact, almost everything in the 16-room duplex has been acquired in the last two years since Carolyne Roehm, 36, married Henry Kravis, 44, one of the new wizards of Wall Street, a pioneer of the controversial leveraged buyout. His multi-billion-dollar deals have made him one of the 50 or so richest men in New York.

In her own right, Carolyne Roehm is a hot fashion commodity. The designing fairy tale princess of the luxurious “I want to feel pretty” look, Roehm specializes in using rich fabrics cut close to the body for other fairy tale princesses and socially ambitious second wives who don’t mind spending $2,000 to $10,000 (U.S.) for a gown. This season, however, she is catering to the masses by introducing a new separates line which retails for between $275 and $1,000, and plans are in the works for a “classic fragrance.” Roehm is also on the rise as one of the great new hostesses of New York. “She always wanted to be a lady of means,” says her former boss and mentor, fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, “but Carolyne got it all so fast.”

She is definitely the girl who has everything, but even for a driven romantic such as Roehm it can all be a bit much—the city place and the Connecticut country estate, the constant black-tie dinners, designing seven collections a year, the worldwide art collecting, the nonstop media attention, his latest 10-figure deal, her French lessons, his philanthropy, their European vacations and gallons of Evian water to try to wash away the circles under her enormous blue (née brown) eyes. “I have to slow down,” Roehm says in a trilly soprano. But somehow she can’t.

There is simply no time to do much more than pose and sleep in her sumptuous apartment, certainly no time to contemplate motherhood right now, or go back to visit Kirksville, Mo., population 9,000, where little Carolyne Jane Smith spent her childhood fantasizing exactly what her life has actually become. “I dreamt all the time how I would enter a room in a dress, make an entrance and Prince Charming would fall madly in love with me.”

Not only did it all come true, but it is safe to say that if Judith Krantz ever met Carolyne Roehm she would probably be astounded to find one of her characters jumping out at her in the flesh—albeit during a chapter in our heroines remarkable career when she is beginning to have these tiny, nagging doubts. “People say, ‘You must be so happy,’ and I say, ‘I’m so tired I don’t have time to think about it.’”

In another era the innately elegant Roehm might have been called filthy rich. But these days she and her husband are leaders of what Women’s Wear Daily have dubbed “nouvelle society.” The nouvelles are a group of brilliant-in-business, extraordinarily driven overachievers who have mostly made their fortunes by age 40: real estate magnates like Donald and Robert Trump, out-of-towners with inherited wealth like Ann and Gordon Getty. They are distinguished by having wads and wads of disposable cash ready to be flung at whatever objet or prominent charity they might fancy. They all work very hard, give big and gain entry surprisingly easily. They also obey the unwritten rule of what it takes to get onto a prestigious board in New York—a donation of $150,000 to $250,000. In this group, the beautiful young wives, dressed by Roehm, often work too, and none more energetically than Roehm herself, who is usually at the office before 8 a.m. Many wonder why.

“She has a vision of what her life is to be,” says her close friend, writer Francesca Stanfill. So much of her life is spent striving to meet that vision.” “I think she’s ambitious,” explains Carrie Donovan, deputy style editor of The New York Times Magazine. Last fall Donovan added to Roehm’s cachet by splashing her dining room on the cover of the Timeshome entertaining supplement under the heading “The New Formality.” “She doesn’t want to be Mrs. Henry Kravis, she wants to be Carolyne Roehm. I don’t admire her as a great designer but to care that much—the Seventh Avenue rag trade is rough work.” Says Roehm, “I have an extraordinary life but I’d give it up in a second before I’d give up my work. Because this is what I was always meant to do.”

Like Ferraris, the bodies that can wear Roehm’s bare and sexy clothes best require a great deal of maintenance. This season, for example, she is cutting a size two, reinforcing the adage that you can’t be too rich or too thin. “I don’t get many requests for cutting a size 14,” Roehm admits. One of the reasons she goes out so much at night, of course, is that Roehm herself is her own best model; she fits her clothes first on her own lithe 5-foot-9 ½ inch, 120-pound frame. Into her third season as a full-fledged designer, she is currently doing a business volume in excess of $6 million a year and expects to break even this season—a quick start-up in the fashion business. Having an appealing personality to match her glamorous looks helps, and she makes herself accessible to the press. As a result, fashion writers have given her enough clippings to fill seven huge scrapbooks. In terms of hype, Carolyne Roehm is the Madonna of Seventh Avenue.

In fact, since she began her business in 1985, with capital from her then fiancé, Henry Kravis (he retains majority interest in Carolyne Roehm Inc.; she and two partners have equal, smaller shares), Roehm has relied on the press coverage of her lifestyle to market her clothes. “She lives the life of her clothes,” says her president and partner, Don Friese. “Carolyne’s customers are a lot like her,” adds Roehm’s other partner, chairman Crawford Mills. “They work hard and they don’t wait for their husbands to give them anything—they go get it for themselves.”

Getting for yourself is the guiding motif of Roehm’s life. She describes herself as “willful and emotional,” a “very animated person but a black person,” who learned early to fake sparkle to compensate for shyness and intimidation. “Carolyne is very transparent in her emotions,” says de la Renta. “When she’s gay she’s very gay and when she is sad everyone knows.” Having melancholy days, however, has never deterred her. Like her favorite movie heroine, Scarlett O’Hara, the tears may flow but her spunk always pulls her out of it; the wilted blossom becomes the steel magnolia. “I always took it for granted making my dreams come true. I’m always so dumfounded when people don’t know what they want,” says Roehm, who knew early on she wanted to be surrounded by beauty.

“I literally spent my life playing dressup as a child. We didn’t live in a neighborhood where there were lots of children, so it was all fantasy—making hats, making corsages.” Both her parents were teachers, and their legacy, Roehm says, was to have raised her, their only child, to be a conscientious self-improver, always taking courses to “better” herself, in gourmet cooking, riding and French.

She became a fine arts major at Washington University in St. Louis during the late 1960s student unrest but wanted no part of it. “I was going to be a famous designer and they were getting in the way of my education.” She told her dorm mates, “I don’t tell you not to smoke it (marijuana); don’t tell me to smoke it.”

After graduation she set out for New York, lived in a tiny apartment with two college friends and dreamed of working for her favorite designer, Oscar de la Renta. She has to settle for designing racks of polyester dresses for a Sears supplier. However, she was soon dating the son of the President of Liechtenstein, entertaining eight for dinner, and within 11 months wangled an appointment with de la Renta.

He hired her, not because of her sketches—he liked her immaculate look. “She was very beautiful, very nicely dressed and she sold herself well,” de la Renta says. Roehm took home $126 a week and was terrified. “I bought sandwiches. I held pins. I thought, ‘How can I make myself useful in order to be desirable to this man?’ I did it by doing all the jobs nobody else wanted to do, like editing fabrics.” Quite as important as her fashion education with de la Renta was Roehm’s exposure to his late wife, Françoise, a renowned hostess who excelled at orchestrating ambience. “Because I was young and looked good in his clothes, when they needed an extra they’d invite me. I was the extra girl.”

The formidable Françoise de la Renta, however, had little patience with Carolyne’s frequent tears over men. “She’d say, ‘There is always another man.’” But for five years Carolyne was hopelessly hooked on a tall German chemical heir named Axel Roehm. “He was dashing and gorgeous and had just the right amount of arrogance.” Axel Roehm has been the only thing that has ever deterred Carolyne from her career. They married and went to Germany. The union lasted less than a year. “He took my life away by taking my career away.” She went back to de la Renta, quit again to return to Roehm, and two months later came back to de la Renta.

When Carolyne met Henry Kravis in 1981 he had three children and was going through a messy divorce. But Kravis, the son of a prominent Tulsa, Okla., petroleum engineer, was becoming very rich by initiating leveraged buyouts, using the assets of a targeted company as collateral for borrowing the money to take over that company. It was not love at first sight between Carolyne and Henry—her mother came along on their first two dates—and Roehm, who towers over him in heels, constantly put him off in order to date others. She says it was his kindness that finally won her over. “Henry’s greatest talent is that he makes you feel good about you.” Then it was her turn to suffer, because the expected marriage proposal was slow in coming—the only proposal Kravis made was when he asked Carolyne to redecorate his country place. At one point there were so many tears that de la Renta himself called Kravis to ask, in effect, what his intentions were. He was told not to worry.

Carolyne, meanwhile, in her ninth year with de la Renta and designing his Miss O line, had decided finally to take the momentous plunge to start her own business. She spent six futile months looking for the right partners to back her until Kravis finally said he would. “I would never ask,” Roehm said. Then she quickly made sure there was a written agreement stating that no matter what happened to the two of them personally, her business would stay intact. She showed her first collection in April of 1985 and it was such an instantaneous hit that on that occasion both Carolyne and Henry cried. Kravis proposed to her a week later in Italy at the ornate Villa d’Este hotel on Lake Como. They dashed home full of plans, purchased their apartment—reportedly for $5.5 million—and immediately sent decorators and curators to scour the world looking for masterpieces to fill its rooms. Says Roehm, “You just can’t go out and buy any old Monet.”

They slept on the floor their first night at the newly minted manse, and two nights later, on Nov. 23, 1985, moments after the electricians finished the wiring, and seven months after purchase, they entertained 101 for their black-tie wedding dinner (the butler had been fired that morning). The next day Carolyne collapsed with the flu.

Although Kravis and Roehm had made the scene as a couple for over three years, marriage conferred a new social status—“couple power”—on both of them. In 1986 Carolyne chaired the New York City Ballet spring gala and, in January, 1987, the gala performance of the Metropolitan Opera’s silver anniversary. It didn’t hurt either that shortly after their wedding, Kravis concluded the $6.2 billion takeover of Beatrice Cos. Inc. of Chicago, the largest leveraged buyout in the history of Wall Street. Since then, the Kravises’ feverish acquisition of art and storming of the social bastion of New York have kept pace with the meteoric rise of Kravis’ fortunes. But today the two are on such a fast track that on a recent “nostalgic day” Roehm admitted to feeling strange receiving invitations from people they’ve never met and said, “I’m at breaking point.” When asked why she doesn’t stop, she replied, “I’ve never learned to say no. And Henry is such a driven human being in terms of not giving in to fatigue.”

To many of their moneyed peers, the Kravises’ lavish life has made them a curiosity. Says a senior partner of a respected trading house, “There is a perception that they’re the ultimate social climbers, mixed with a sense of awe and confusion about this sort of grotesque spending. Some don’t understand it, others think it’s horrid, and a lot say, ‘Hey, I want that too.’”

Roehm has no liberal guilt. “I’m short-tempered with people who say ‘greed’ and ‘you have so much money.’ Do you know how much is being given away?” Roehm bristles. “Kravis has donated generously to the opera, ballet, New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital.” Last May Roehm herself co-sponsored a four-day AIDS benefit in New York and California.

“You see, I always believe that you can if you really try,” says Roehm. “I don’t care how many disadvantages—I mean terrible health is a disadvantage, but look at the disabled who get up and do things. So don’t talk to me if you’ve got poor parents.”

Roehm will continue to slave away, thank you. And it’s not only her work ethic that sets her apart. “Carolyne’s not like a lot of suddenly rich women, who can’t remember that three years ago it wasn’t always private jets,” remarks a close friend.

Roehm’s quest, it seems, is not merely to succeed but to strive for perfection—right down to the George III silver that holds her carefully arranged roses on the English Regency table during a dinner at which three sets of gold-trimmed Limoges china will be used. Careful records are kept so that, if the same guest is seated beneath the elaborate circa 1800 crystal chandelier in the dining room with the coral damask-covered walls, he will never have to eat the same roast pheasant, risotto with porcini mushrooms or homemade pistachio ice cream in a meringue shell twice. That would never do for the lady who so deftly makes so many of her dreams come true.

Next December, for instance, Roehm will toss a “Gone with the Wind” costumed bash to benefit the New York Public Library. “This is my chance to play Scarlett,” Roehm enthuses. “I’m going to wear green curtains and the whole thing.”

We await the mini-series.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments