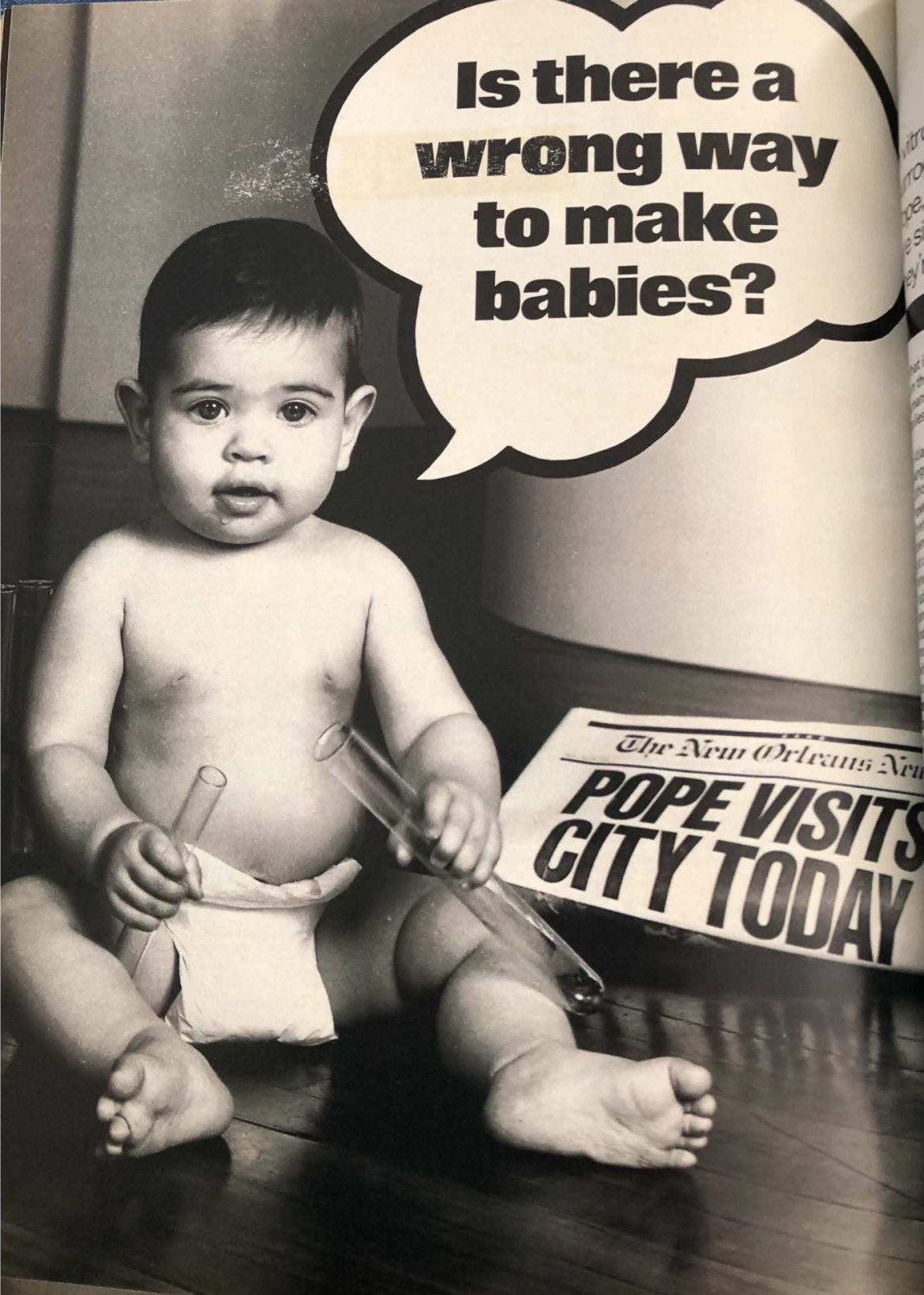

Original Publication: Glamour Magazine October 1987

In vitro, frozen embryos, surrogate motherhood: To the Pope, all these techniques are sinful; to childless women, they’re a gift from God.

“What is technically possible is not morally admissible.”—from the Vatican’s Instruction on Respect for Human Life in Its Origin and on the Dignity of Procreation: Replies to Certain Questions of the Day

In Atlanta, Georgia, Laura Gebhardt (her name has been changed to protect her privacy) is such a traditional Catholic that she still prefers the Latin mass. Scientifically, however, the thirty-three-year-old lawyer is on the forefront of the new reproductive technology. She has been searching for a way to have children ever since she got over the initial shock of having to have her uterus removed. In the last seven years, Gebhardt and her husband have been on a desperate quest to become parents, traveling to fertility centers across the country and even consulting with specialists abroad. Three months ago they had a “surrogate carrier” implanted with eggs that had been surgically extracted from Laura’s body and then fertilized with her husband’s sperm in a petri dish. Theoretically, more than one embryo could be carried to term and the Gebhardts could end up with three babies all at the same time.

“We’ve committed $50,000 a year and sometimes work a hundred hours a week each so that we can try over and over again until we succeed,” says Gebhardt, who originally considered using two surrogates simultaneously to increase her chances of success. She believes that the surrogate who will bear her child is merely “baby-sitting during this critical time of the child’s life,” and the surrogate—“a woman who loves children but can’t afford to have more,” according to Gebhardt—agrees.

Because Laura Gebhardt believes herself a deeply religious person, she has been hurt and angered by the Vatican’s recent ban on artificial reproduction. “This announcement makes me a mortal sinner; it means I can’t take the sacraments. But I don’t feel immoral, I feel betrayed.” She is on the verge of leaving the Church.

In San Francisco, California, Cynthia Clark (her name has been changed to protect her privacy), thirty-two, full-time mother of two traditionally adopted children, ages two and four, backs the papal edict 100 percent. The fertility problem in their family is her husband’s, so Clark could become pregnant—but only through artificial insemination, a solution she has rejected. “I would never want a stranger’s sperm,” she says. “No way—it gives me the creeps.” Clark, who once counseled unwed mothers, was able to adopt more easily than many. During each adoption, however, she and her husband went through periods of intense anxiety because the birth mothers had six months to change their minds. Despite those agonizing waits, Clark never considered having children by artificial means. “It’s important to me that my two children came about naturally, as products of sexual intercourse, and I think it will be important for them to know that later. I go along totally with what the Church says on this, along with other issues like abortion. All life issues are interconnected. The reason it’s hard to adopt children now is that there have been twenty million abortions since 1973.”

In La Grange, Illinois, Bonny Cronin, thirty-eight, a flight attendant on leave of absence, is the mother of two-year-old twin girls—“test tube” babies Cronin became pregnant with through in vitro fertilization after seven years of trying to conceive naturally. “The Church can condemn abortion, but how can it condemn giving life?” Cronin asks. “God gave us these little bundles of love. No matter how you get them, they’re yours, and no one can say it’s a sin.”

Cronin wants to raise her children as Catholics but worries that they’ll be singled out some day for being different. “I won’t like it, years down the road, if I want to send my children to Catholic school and they’re taught that their parents committed a sin in having them. I am speaking out now because I don’t want anyone to think I sinned—I didn’t!”

Not since Humanae Vitae, the 1968 papal edict banning artificial forms of birth control, has a Vatican pronouncement been so controversial—especially now when so many women are postponing pregnancy until they are older and one in seven married couples who have not been surgically sterilized are infertile. The Vatican’s stance, however, is uncompromising.

In a sweeping, stiffy worded, forty-page document issued last March, the Church gave only a partial okay to amniocentesis (permissible only when not performed as a possible preliminary to abortion), but it did approve fertility drugs and surgical operations allowing natural fertilization via intercourse to take place. In vitro fertilization, artificial insemination and the freezing and transfer of embryos were banned (because, among other reasons, these techniques rarely use all of the mother’s fertilized eggs—zygotes—which the Church considers to be human beings). The Instruction also examined fetal research, surrogate motherhood, the role of procreation in marriage and the pain felt by infertile couples. By challenging the moral neutrality of science and humankind’s manipulation of that science, the document tackled some of the most complex and delicate ethical questions of the day. But its essence can be summed up in one work: no. Catholics who follow the teachings of the Church are forbidden to tamper with the creation of life. Any high-tech assistance in the process of conception is out. The Vatican concedes that “sterility is certainly a difficult trial,” but stands firm: “Marriage does not confer upon the spouses the right to have a child, but only the right to perform those natural acts which are per se ordered to creation.”

Such an across-the-board prohibition written by celibate men is not easily acceptedby many Catholics—particularly today’s women who are used to getting what they work for. “Who are these men—the same ones who said the world was flat?” asks Sue Palazzo of San Juan Capistrano, a Catholic convert from Quakerism. The thirty-nine-year-old mother of three supports the Church’s ban on abortion, but not its other teachings on sexual matters. “What they say doesn’t affect me,” she states. “If every woman who practiced birth control got up and left the Church, how many would be left?” Says NBC News correspondent and anchor Maria Shriver, thirty-one, “It all boils down to your definition of sex. The Church teaches that sex equals procreation—so if a doctor can help two people who can’t of their own volition conceive, why not? I don’t believe in having to be a martyr for the rest of your life. If I was involved in trying to have a baby and couldn’t I would pursue artificial methods.” Declares Mary Gordon, thirty-eight, a Catholic who’s a novelist and the mother of two children, “They’re afraid of separating procreation from sex because then people can have sex freely.” She calls the document “an embarrassment in front of the world.”

The greatest outcry against the Instruction has come from those who believe that infertile married couples should be able to use in vitro, artificial insemination or the implanting of previously frozen embryos. After all, say critics, the Church has always taught that the purpose of marriage is to have children and that the pleasures of lovemaking must be linked to babymaking. Now married couples who are willing to conceive without enjoying those pleasures are being denied. “It’s just one more guilt trip for childless couples,” complains thirty-four-year-old Audrey Myer of New Jersey, the mother of a three-year-old son and codirector of the central New Jersey chapter of the infertility support group Resolve. “The only thing that stopped me from having in vitro was money.” Says Karen Sue Smith, an assistant editor of the Catholic lay magazine Commonweal, “Once you emphasize family as much as the Church does, you magnify the pain of people who can’t have children.”

That pain often becomes the driving force of infertile women’s lives. Janet Nordlinger, thirty-seven, of Santa Monica, California, spent three years and underwent four surgeries in order to conceive. “The thought of never having a family terrified me,” she admits. “It was the most important thing I wanted since childhood. When I hear about the Instruction, I thought it was pretty shocking. I spent more time thinking about it than any other Church ruling, because it touched my life. If I couldn’t have had my son through surgery, I would have had in vitro. I would view it in the same way I’d view needing a heart transplant.”

Even within the Church hierarchy, women like Nordlinger are finding supporters. Already one prominent U.S. Cardinal has expressed sympathy for those suffering due to infertility. In a speech to student physicians and researchers at the University of Chicago last spring, Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, head of the archdiocese of Chicago and the American Catholic Bishops Pro-Life Committee, spoke of the “pain of loving couples, Catholic and non-Catholic,” who desperately want a child. “My heart reaches out to them,” said the Cardinal, who in Church politics is considered a moderate, not a radical. “We must offer them love, support and understanding. And in the end, after prayerful and conscientious reflection on this teaching, they must make their own decisions.”

At Chicago’s Michael Reese Hospital, Edward Marut, M.D., head of the Infertility Clinic and a Catholic himself, reports that his patients are taking their Cardinal’s advice. Fully 40 percent of his in vitro fertilization patients are Catholic, and so far no one has discontinued treatment because of the Vatican document. Still, he concedes, he has spent considerable time talking to Catholic patients about the Instructions.

“It’s upset them. I give them my understanding of the purpose of the document: to provide a very conservative, very mainline Catholic stand by which Catholics—and all people—can formulate their own consciences.” If a Catholic physician such as himself followed the edict literally, Dr. Marut claims, he could no longer practice his specialty. “It’s like telling an oncologist that cancer is natural and because chemotherapy is artificial you can’t use it.”

Statistically, Catholics do not differ significantly from the rest of the population in their opinion of the Instruction. In a U.S. News & World Report/CNN poll taken shortly after the document was released, only 31 percent of the general population and 35 percent of Catholics approved of the edict. This reflects the independent stance of U.S Catholics over the last twenty years. A 1982 survey by the National Center for Health Statistics found that 93 percent of American Catholics who engaged in sex used birth control. Says Tom Smith, senior study director of the National Opinion Research Center, “If you can’t convince Catholics not to use birth control, I don’t see how they’re going to be persuaded not to use these hi-tech fertilization methods.” Says William McCready, a leading Catholic sociologist, “By now Catholics have chosen up sides and further pronouncements don’t mean anything.”

Despite overall opposition to the document among Catholic women, there is strong support for parts of the Instruction, especially its condemnation of surrogate motherhood. One of the Vatican’s objections is that surrogacy “is contrary to the unity of marriage,” creating an imbalance between the biological parent and the parent who has no genetic tie to the child, grounds with Catholic ethicist and mother Sidney Callahan agrees. “True,” she writes, “The bypassed parent may have given consent, but consent, even if truly informed and uncoerced, can hardly equalize the imbalance.”

“I would rather be a prostitute than a surrogate mother,” Mary Gordon declares. Says Frances Kissling, president of the liberal, national organization Catholics for Free Choice, “I’m opposed to selling organs, I’m opposed to selling blood and I’m opposed to selling babies.” Shannon Branham, a single twenty-six-year-old legislative aide from Lansing, Michigan, echoes a similar thought: “It’s gotten to the point that women can’t get pay equity in the work force so we have to start using our bodies again for money.” Other women oppose surrogacy for more personal reasons: They don’t want their husbands to create such an intimate bond with another woman, even if all the means used are artificial. Says Maria Shriver, “I’m not open enough to let my husband or myself get into that kind of arrangement.”

Few agreed with Laura Gebhardt that her surrogate was only “baby-sitting” during pregnancy. “I find that questionable,” says Lisa Sowel Cahill, Ph.D., professor of theology at Boston College. “To call carrying another woman’s fetus ‘baby-sitting’ is a very pragmatic and utilitarian approach.” Jean Hoefer Toal, a forty-four-year-old lawyer and mother who is chairman of the Rules Committee of the South Carolina House of Representatives, called that view of surrogacy “a terrible denigration of women. Viewing them as just a container is very distressing to me. I question the idea that you can have anything you want as long as you can pay for it.”

Nonetheless, the surrogacy business is booming, says Noel Keane, the Catholic lawyer from Dearborn, Michigan, who arranged the surrogacy contract in the celebrated Baby M case. According to Keane, cases like the Gebhardts’, in which the parents provide a fertilized egg, the surrogate only the womb, are the wave of the future. “In legal terms, it’s easier,” he says, because in Michigan, where he practices, a judge has already ruled that such a surrogate has no claim to the baby. Keane conceded he has not read “one word” of the Vatican Instruction, but he did stay away from the Communion rail last Easter Sunday because he “did not want to risk a verbal confrontation.” Even so, Keane remains undeterred and boasts that very soon an American surrogate carrying the sperm and egg of a Japanese couple will give birth to a Japanese baby.

As science surges ahead, the questions posed by ever more sophisticated reproductive techniques become more complicated and more troubling to Catholics and non-Catholics alike. By the early 1990’s, for example, it’s possible that there will be egg banks where women in their twenties can leave young, healthy eggs to be frozen until they wish to use them at age thirty-five or forty, or whenever their careers permit. Even then they would not necessarily have to bear their own children if they could afford a surrogate. Within a generation it will probably also be possible to shop for genetic traits, at least single-gene traits such as red hair, green eyes, sex or skin color.

“It gives me a headache just to think about it,” says Theo Hayes, thirty-two, an interior designer expecting her third child in Potomac, Maryland. States Ana Veciana-Suarez, thirty, a Miami newspaper reporter who’s the mother of two as well as a foster-mother, “Pure genetic research should continue, because it can help with birth defects and conception—but when do you start breeding perfect blond, blue-eyed children, and who decides whether you should?” Worries nurse practitioner Elizabeth Magenheimer, thirty-seven, the mother of two in New Haven, Connecticut, “We’re a fast society and the faster we do things the less we monitor them. I don’t think society will ever go backward, so there has got to be a conversation between science and religion. But I don’t think the Church is listening, and science thinks science is a cure for everything. It’s petrifying.”

The need for direction is obvious. Already, for example, the U.S. Patent Office is embroiled in controversy surrounding its decision to grant patents for the making of new life forms, all the way up to mammals. But amid this confusion the Vatican has taken a stand so strong and so negative that the strengths of its argument are simply being ignored. By simply saying no to everything in advance, the Vatican appears to be trying to slow down, if not stop entirely, what most of the scientific community considers breakthroughs—but which challenge the “sanctity of life,” as it has always been known in the Judeo-Christian ethic. In proscribing fetal research, for example, the Vatican is calling for a halt to a practice that is just beginning the use of fetal tissue to treat disease. It has been rumored that fetal brain tissue has been used experimentally to treat Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases in China. The choices posed by that breakthrough have never been faced before. Robert J. White, M.D., a distinguished Cleveland neurosurgeon and professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve Medical School who is a Catholic and a member of the Vatican’s Committee on Biotechnology as Applied to Man, asks, “If you brought in your grandmother with Alzheimer’s, and you were told she could be helped by using fetal brain tissue, what would you do? I personally don’t approve of the practice, but I’d guess that 95 percent of people would want to use the tissue. But should aborted fetuses be recycled this way? Who speaks for a dead fetus—the parents? The doctor? There is also the issue of how much it is worth. What are the costs involved? What’s my charge? The aborted fetus is now a commercial enterprise.”

So just as there are those who worry about the exploitation of poor women in “breeding farms,” there now exists the possible scenario of women getting pregnant to sell a product. “If an aborted fetus is worth $2,000, a young woman can get pregnant any number of times and abort it for the money,” says Dr. White. Is he envisioning a scenario too farfetched to consider? He doesn’t think so. “If it’s found that fetal tissue can assist in Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, in contemporary American society, I see tissues being used this way.”

Dr. White, who helped organize a group of international fertility doctors who were invited to Rome in 1984 to converse with Vatican theologians, gently suggests that parts of the Instruction, particularly the one concerning in vitro fertilization for married couples, may not stand the test of time. “We don’t want to use situation theology, but we don’t want to think these decisions are carved in theological stone, either,” he says. Dr. White recalls that the Vatican has struggled with science before and been judged wrong. “I call this the Galileo effect,” he says, referring to the Church’s seventeenth-century persecution of the astronomer for saying the planets revolved around the sun. “The big issue today is not astral physics but human biology. Let’s not find ourselves and our poor theologians with egg on our faces in the twenty-third century.”

Will the Church’s stance be an embarrassment in the future—or will it be seen as an important first step in subjecting science to ethics? In his attempt to get all of us to reflect on the most basic questions of giving and receiving life, the Pope has aroused support from ethicists as well as concerned Catholics. Daniel Callahan, director of the Hastings Center, a think tank on biomedical ethics, has stated that “this is by no means a document that pits the Pope as a moralist against everyone else who is weighing the ethics of technology.” “They are trying to persuade people to connect the sexual experience with love and parenthood, which is something we lost sight of in our society,” says Dr. Cahill. Agrees Karen Sue Smith of Commonweal, “The document is legalistic to the absurd, but it causes us to slow down and think about things in our culture—the idea that science is not morally neutral and not inevitably in our best interests. Is our culture so commercialized that we’re willing to commercialize almost everything—our bodies, our children?”

According to some women, the answer is already yes. They see themselves and their peers as too materialistic and too apt to consider babies as just another form of high-status consumer goods—a product begun at conception, for a price if necessary, and subject to termination if the goods are damages. “I’m a yuppie and I know people who think a baby is like a Volvo,” says Alyce Robertson, a married thirty-two-year-old county official in Miami. “ ‘See my baby dressed in designer clothes.’ If my husband and I cannot have children, I am more than willing to find some other outlet to give that maternal love—by volunteering, for example.”

Declares Loretta Marra, twenty-four, an unmarried Ph.D. candidate in philosophy, “People think they have a right to something that is a privilege. To me, thinking you have the absolute right to have a child is like saying you have the right to be perfect. If you’re born without a right arm, who do you complain to? These artificial methods are just another example of the complete loss of respect for the sacredness of human persons. In medicine today you have this absurd situation where in one room people are performing abortions and in another people are frantically trying to assist the process of human creation in a petri dish.”

To a mother hugging her baby at night the sacredness of life seems very real. But does that mean another woman should be denied that deepest of human emotions—mother love—on the technicality that she cannot conceive naturally? “It’s God who gave us this medical technology,” argues Bonny Cronin, the mother of the “test tube” twins. “I prayed to God, not the Catholic Church, to get pregnant.” Should every couple who wants a baby and can afford it be helped to have one—even if they’re IV drug users carrying the AIDS virus, or an unhappy married couple seeking a baby to heal them? Or should babies be made to order only if certain criteria, perhaps similar to those used by adoption agencies, are met? One criterion is already firmly in place: a big bank balance. Ethicists would probably choose different ones.

Like so many women attempting to be thoughtful about these issues today, Shannon Branham is both anxious and confused. “I’m frightened because this seems to be an instance where technology has gone ahead of society and we haven’t had time to develop ethics or values for it. You want to look to your church as your spiritual guide in these things, but instead they issue a sweeping denial of everything. There’s no relief for people out there.”

“The real issue is how is this document going to be implemented,” says Dr. Cahill. “I doubt priests will be asking parishioners, ‘Have you used any artificial reproductive techniques lately?’ People will use them and go to church anyway.”

That being the case, it seems inevitable that a whole new generation of baptized Catholic babies will grow up unsanctioned by Rome but very much treasured and loved by parents who still call themselves Catholic.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.