Blueblood War

Rich, aristocratic Wasp families usually do not allow this level of dysfunction to become public. Yet here was Philadelphia socialite Edgar Newbold Smith, whose ancestors arrived on the banks of the Delaware River in 1677, listening to a judge sternly lecture him about his son Lewis du Pont Smith in a federal courtroom full of reporters. On this last day of 1992, the impeccably pedigreed elder Mr. Smith, who had married into the du Pont money, found himself in Alexandria, Virginia, the focal point of a trail in which he was accused of conspiring to kidnap his 36-year-old son. In the company of three co-defendants, whom the judge charitably referred to as “the gang that couldn’t shoot straight,” Mr. Smith had heard the government portray him as the financier of a plot to “snatch” Lewis in order to “deprogram” him.

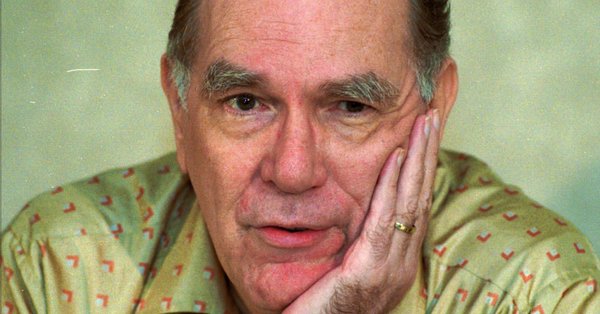

For eight years, the determined Mr. Smith, a 66-year-old investment manager, a former all-American football player for Navy, and renowned sailboat racer, has waged a Promethean paternal battle involving 20 legal actions, more than 3,000 pages of psychiatric testimony, $1 million in legal fees, and an arrest warrant for burglarizing his son’s house. He did it all for love, Newbold Smith explains to me, to wrest the son he felt closest to from the clutches of the aberrant movement founded by conspiracy theorist Lyndon LaRouche, who is serving 15 years in prison for defrauding the I.R.S. and swindling his supporters. Smith believes this “cult” brainwashed his son.

After Lewis, whose inheritance is valued at roughly $10 million, gave a LaRouche publishing arm $212,000 in 1985, and was poised to give $75,000 more, the family succeeded in having a Pennsylvania court declare him “incompetent” to manage his financial affairs, and this public disgrace has so humiliated Lewis that he denounced his parents and refused to have any contact with his two brothers or his sister. “Do you have the right to go into court to manipulate your son, humiliate him, destroy his reputation, and give him a stigma? He wants to possess me like his yacht,” Lewis Smith declares to me about his father. It’s been “damn loyal of me, thinking in terms of the money, time, and publicity I’ve sunk into this,” counters his father. “I’ve been very generous to my son, because I wanted to rescue him, pure and simple. Because I think he needs rescuing.”

At the heart of the matter are opposing attitudes toward patrimony and preservation of capital. There is also a small and willful woman of Italian extraction, Andrea Diano-Smith, whom Lewis married six years ago—not out of the Social Register, as his mother, Margaret du Pont Smith, is, but out of South Philly. To his family’s horror, Andrea shares her husband’s zeal for LaRouchian dogma and keeps him happy feeding him the pasta he says he never got at home because it was considered “peasant food.”

In the courtroom, Judge Timothy Ellis was appealing to Smith father and son to get beyond the underlying battle over Lewis’s inheritance and rise above petty snobbishness. But that hardly seemed possible. For nearly three weeks the judge had been hearing tapes of outlandish discussions among Newbold Smith and the three other defendants, who all sounded as if they had been reading too many copies of Solider of Fortune.

The scenarios for “lifting” the du Pont heir included sexual bait in the form of a skinny blonde cocktail waitress; if she could just lure the six-foot-four, 225-pound Lewis into a conforming position, he could then be blackmailed, or stuffed with Quaaludes or shot with a tranquilizer gun and hustled across state lines to his father’s 44-foot racing boat, Reindeer, which would then speed down the Inland Waterway to an unnamed place “where bribery is king.”

Since Lewis was so big, and usually surrounded by a gaggle of LaRouchies, they would have to surprise the former national prep-school wrestling champ when he was unguarded. One suggestion on the tapes was proffered by defendant Donny Moore, b.s. artist extraordinaire, an ex–deputy sheriff and former tentmate of Oliver North. Moore, who had spent years investigating LaRouche in Loudoun County, Virginia, where LaRouche settled in the mid-80s, rattled on and on about “a grenade in the chicken coop” and “busting the covey.” Newbold Smith had originally hired Moore to do surveillance work on Lewis because he was convinced that the huge 19th-century stone house Lewis was buying in Philadelphia’s tony Chestnut Hill section was going to be used as a LaRouche headquarters—a place where little old ladies might be enticed to part with their life savings. Unscrupulous fundraising was one of the things Lyndon LaRouche was behind bars for, and Newbold Smith was terrified that Lewis might get caught for the same thing. Throwing “a grenade in the chicken coop” meant planting a story in the local press which would “bust the covey”—scatter the LaRouchies and leave Lewis and Andrea vulnerable to a “lift.” On one tape Moore bragged, “I’ve got stuff, man, that will chill the pubic hair on an ant 500 miles in a rainstorm.”

Last June 26, Moore visited another out-of-work deputy sheriff in Loudoun County, a would-be Serpico named Doug Poppa. Poppa had been fired for being too available to the media about a case in which his testimony had contradicted the accounts of others in the department and he had helped a man convicted of attempted murder get out of jail. Moore felt sorry for Poppa, and asked him if he wanted to help in kidnapping a du Pont. Poppa initially didn’t know what a du Pont was, but he found out soon enough, when he first went to his lawyer, who also did work for LaRouche, and then to the F.B.I., which wired him to inform for the law. Poppa told the F.B.I. that a kidnapping was imminent, and for the next three months he recorded 60 hours of tape some of it in Newbold Smith’s home.

Last August 19, Donny Moore took Poppa to meet Robert Point, also known as Biker Bob, an ex-cop who had earned his nickname in South Amboy, New Jersey, tracking down stolen motorcycles. Point had been forced to give up that line of work because, as his defense lawyer explained to the jury, he’s a narcoleptic—“the man can’t stay awake.” Biker Bob did manage to put himself through night law school, however, and one of his clients was an adviser to Newbold Smith named Galen Kelly. Moore told informer Poppa, “Biker Bob cleans up Galen Kelly’s messes.”

In the netherworld of cults, Kelly is an infamous upstate–New York deprogrammer-kidnapper on hire to parents in despair, and he claims hundreds of successes. “I have no apologies whatsoever,” he tells me. “Have there been occasions where I’ve taken people forcibly, involuntarily? Yes. If you want to call that kidnapping, call it kidnapping.”

Over the years Newbold Smith has paid Kelly $30,000 to conduct surveillance of Lewis and negotiate with LaRouche operatives about having him turned over to his family. For most of last summer, however, Galen Kelly—who boasts that he has been hauled into court several times but has never lost or been found guilty—was on the lam. (In May he had been involved in a kidnapping that went bad: he snatched the wrong person off a Washington, D.C., street and told her his name. When Kelly presented the snatchee, a woman in her 30s, to the aggrieved mother who had hired him, the mother said, “That’s not my daughter.” In fact, she was the daughter’s girlfriend, a member of the same sect, the very person the mother wanted her separated from. The woman then reported the incident to the F.B.I.)

The jury listened to Galen Kelly muse on the tapes with Biker Bob, Donny Moore, and Poppa about hiring British commandos to do the “wet work” in lifting Lewis, or perhaps subcontracting the job out to bikers, a scenario Moore speculated might cause Lewis to end “sneakers up in a ditch.”

The F.B.I. had heard enough. Special agents arrested Donny Moore, Biker Bob, Galen Kelly, and Newbold Smith. It was the first time the federal kidnapping statute had ever been applied to an alleged kidnapping conspiracy within a family. For a Main Line blueblood, Newbold Smith had been keeping very strange company.

The trial attracted a parade of the unusual, as one Philadelphia Inquirer headline put it. There were parents of children who had joined cults and Lyndon LaRouche operatives. Reporters were presented with damning affidavits about Galen Kelly from a group calling itself the Deprogramming Survivors Network, which appeared to be operating as a front for the Church of Scientology. Their mortal enemy was the Cult Awareness Network (can), a clearinghouse for cult information based in Chicago, with which Kelly was affiliated and to which Newbold Smith had contributed generously.

Andres Diano-Smith’s vivacious mother, Martha Diano, wearing a fur hat and boots, attended court regularly, as did Lewis’s mother, Peggy, dressed down skirts and sweaters or slacks, a black velvet headband holding her blunt cut silver-blond hair. She would sit alone among the spectators, betraying no emotion. Martha Diano said bitterly of the Smiths, “They have two tickets on the aisle to burn in hell.”

The prosecution behaved as if they had an open-and shut case, in spite of the fact that two days before the trial began it has been revealed that their star witness, Doug Poppa, had gotten so ticked off that he had not been paid by the F.B.I. for his work that he demanded $250,000 before he would show up to testify. Although he settled for considerably less, the defense made sure the jury knew about his demands. From then on, Poppa’s motives were suspect.

Newbold Smith spent two and a half days on the stand and admitted that he had discussed kidnapping Lewis numerous times, even with F.B.I. agents, but that it had all been hypothetical. The jury listened as Smith and Lewis’s younger brother, Henry “Hank” Belin du Pont Smith, talked about Lewis and his father’s previously extremely close relationship, which had begun to unravel early in 1985 as Lewis became more and more enmeshed in the LaRouche organization. “I felt he became withdrawn from the family, felt he said some strange things, such as that his mother contributed to his grandmother’s death by pulling the tubes,” said Newbold Smith. “It was very clear to me that he had become captive of a cult.”

John Markham, Smith’s effective attorney, who as a government prosecutor had gotten the conviction against LaRouche, asked Smith if his feelings toward Lewis had changed. “There has never been a time that I didn’t love him,” he answered. “If I don’t love him, I wouldn’t be here today.”

That love was sorely tested. One day, totally unannounced, Lewis showed up in the witness room. Prosecutor Larry Leiser had hoped that the judge would allow Lewis to testify against his father, but the judge had refused. When Peggy Smith saw her son in the room with Doug Poppa, she approached him, but Poppa summoned a marshal, and Lewis refused to speak to his mother. During the closing arguments, Biker Bob’s lawyer, Bernard Czech, wrung out the courtroom by reciting the lyrics to the Elton John hit “The Last Song.” As Czech recited, “I never thought you’d come / I guess I misjudged love / Between a father and his son,” Peggy du Pont Smith’s sobs filled the courtroom.

The next night, after the jury had been out for six hours, Lewis marched dramatically into the courtroom in a long gray overcoat, with the unsmiling Andrea in tow, and sat in the front row of the spectators’ section with Doug Poppa, his father staring at him from the defense table. “He was like a witness at the Rome Colosseum,” Newbold Smith said to me later. “I wasn’t in the least bit surprised, because I knew who was running that show.”

The jurors sent the judge a question about whether merely considering kidnapping as a viable option constituted a conspiracy or whether there had to be an agreement to act upon it. There had to be a specific agreement to carry out the plan, the judge told them.

“Not guilty,” the foreman’s voice repeated for each count for every defendant. Judge Ellis then delivered a dramatic soliloquy “about a tragic rift between a father and son,” admonishing Newbold Smith and telling him to seek to repair his relationship with Lewis. “If you have a lot of money and then you give money to your son, you ought not to worry about how he is going to spend it. If he has silly political views, grant him that.” Of Lewis, who was not present, the judge said, “I would hope that young Mr. Smith would realize that no political view he has, nothing he wants to do in his life, is any more important than his relationship with his father.”

Lewis was outraged. “My mother and father have gotten into bed with thugs, perverts, and gangsters,” he told me. “How could they put their own son at risk with all of these gangsters?” He added surprisingly, “I still love my father. You can hate the sin and love the sinner.” Newbold Smith called me to discuss the judge’s remarks urging him to repair his relationship. “I felt like rising and saying, ‘Your Honor, I have no way of doing that. He is kept like a monk in a cell at the top of Mont-Saint-Michel.’”

Lewis Smith has never seen the large, vaguely Colonial house in an affluent Philadelphia suburb into which his parents moved last May. But he would recognize the antique sofas, the old Orientals on the hardwood floors, the James Buttersworth sailboat painting in the library. The Smiths, who look as if they just emerged from a John Cheever novel, are in the library—the same room, Newbold Smith points out, where informer Doug Poppa secretly recorded him talking about “lifting” Lewis.

Following the trial, Lewis and Andrea left for a two-week vacation in the Caribbean, and Lewis sent his parents a needling “Dear Mom and Dad” postcard, telling them that he was having fun “swimming and snorkeling” without surveillance, and that they could have dinner together “after you invalidate the incompetency.” To the Smiths, however, who had promised moments after the trial that they would no longer oppose him, it was easier said than done. All Lewis and his lawyer wanted was for the Smiths not to counter a new petition, or, better yet, for the Smiths to join them in asking the judge to drop the court’s protection of Lewis’s finances. Instead, the Smiths filed a new petition that would require that Lewis be re-examined by a court-appointed psychiatrist in order to be found competent. Lewis has heatedly objected. “If we went about it his way,” said Newbold Smith, “it would be that what we asked the court to do eight years ago was wrong. It wasn’t wrong.”

Besides, how could they assure the court that Lewis was O.K. if they couldn’t see him or talk to him? But Lewis remains adamant that it is a matter of the deepest honor and principle, and that he will never go near them until they do whatever it takes to nullify the incompetency “There’s a way of doing this,” Peggy Smith maintains. “Take a look and see if Lewis has changed. If he looks like he can control his resources, we say fine. If he wants to piss away all the money he has, let him. We were protecting him from doing wild things.” “People do give money,” Mr. Smith interjects. “You give money to the Catholic Church, but you don’t give half your fortune away, not to an organization considered as being a … ” He lets the sentence hang. “Peggy particularly does not like this label of his, which is a stigma, but we need a little cooperation from him.”

“Please explain to Lewis I never thought he should have been called an incompetent per se,” says his mother. “Incompetent to manage his financial affairs, yes, but incompetent to tie his shoelaces, no. I never knew it meant no right to vote, no right to marry. Don’t get me on the subject of darn lawyers.”

Lewis and Andrea and Andrea’s mother think Peggy Smith should be standing up more for her husband. “She bore that son. She did not bear her husband. If your husband dies, you get another husband. You can never replace your son, never,” says Martha Diano. “If he wants to go to bloodlines, Lewis is more of a du Pont than Newbold is.”

“Tell him I would love to get the judge on the phone, but I can’t,” says Peggy Smith. “Can’t I just have a sandwich with him and Andrea somewhere? With me alone?” Her husband looks sharply at her. “Never with you, Newbold, for years to come,” Peggy Smith says. “With me.”

“He doesn’t have to leave LaRouche,” Lewis’s mother continues. “That’s not the way I’d put it,” Newbold Smith interjects. “I’d still like him to leave.” “But he doesn’t have to,” Peggy Smith reiterates. She returns again and again to the theme of how she’d like to meet Andrea, to talk with her. But “she’s been told I’m evil.”

When she leaves the room, Newbold Smith says, “I’m in despair all the time about this. I just don’t know where to turn. Most people say I ought to just drop it, forget it, but I wouldn’t be talking to you if—You are a message carrier. I’m trying to get a message of reason to him.” He hunches forward in his straight-backed chair. “Deep in his heart, he knows I care about him. You don’t take 28 years in your life and say it’s all in the ash can.”

Newbold Smith frequently evokes the similarities between himself and Lewis. “Lewis has a wild temper; so does someone else.… Lewis has a very, very stubborn streak in him; that works two ways, by the way.” Even their lawyers agree. Lewis’s lawyer James Crummet tells me, “Lewis is a chip off the old block … a hothead and a bully just like his dad.”

Growing up on a 64-acre estate outside Philadelphia that his mother calls a farm, Lewis kept all his father’s medals and his 10 letters for sports on his bedroom wall. “He just patterned his life after me,” his father says. Lewis excelled at the same sports his father had—football and wrestling—and Newbold Smith went to everyone of Lewis’s high school football games. “Dad and Lewis used to wrestle in my parents’ bedroom until one day Lewis picked Dad up over his head and deposited him on the floor,” remembers Lewis’s brother Hank, and up-and-coming yuppie money manager in Philadelphia. Despite their vast wealth, there was pressure on the children to be achievers. “What my father had seen over several generations was various people in the family being duped over silly ventures. He instilled the importance of not pissing away what was given to you instead of what you earn on your own.”

Lewis remembers growing up hearing an additional set of rules: “Always tackle low, the invincibility of the United States Marine Corps, the holy righteousness of the Church of England, and never marry a Catholic.” “Every time I went on a date, my father would rush to the Social Register to see if she was listed.”

Early on Lewis was found to be dyslexic; math was always a major problem for him. When he was 15, his father suffered a fall from a horse that left him paralyzed for a time and with a slight limp today. Lewis says the accident exacerbated Smith’s serious drinking problem. Just was he now wants to rescue Lewis from Lyndon LaRouche, so Lewis, early on, wanted to rescue him from alcohol, and was eventually responsible for getting him into A.A. Two years earlier, Lewis’s mother was also hospitalized, for depression. The turmoil at home interfered with Lewis’s learning, and his athletic prowess was apparently the mainstay of his self-esteem. After boarding school, Lewis was recruited nationally, and went to the University of Michigan on a football scholarship. He also continued to wrestle. But his hopes were dashed forever when he was diagnosed with having a congenital neck problem.

By all accounts, Lewis was fun-loving and bighearted, and he had lots of girlfriends. Though he signed his papers Lewis du Pont Smith, he was not a snob. Doug Beath, his college roommate and then best friend, says Lewis seemed to need to prove he could be successful like his dad. “Once, he told me to buy all these gold stocks. Gold was about to take off and we would be heroes,” Beath recalls. “As nice as he was,” he did have “the need to do something big, cause some noise.” Says Hank Smith, “Lewis was always trying to hit it big and to hit it quickly.”

Twice Lewis got duped financially and had to have his father bail him out of trouble—once with silver bullion, for $25,000, and once with an $80,000 venture in walnut groves. On the other hand he made a windfall of $800,000 from selling his Wang stock at its height. It was part of that windfall that he gave to LaRouche.

Lewis’s first full-time job after college, distributing Time Inc. magazines in Rhode Island, which he got through family connections, was a disaster and lasted only a few weeks. In retrospect, his mother, whose own father had sat on the boards of both Du Pont and General Motors when Du Pont owned the controlling interest in G.M., and founded a prosperous private-aviation company, which Lewis’s older brother, Stockton, now heads, says she regrets that “we tried to steer him” towards business. Lewis was attracted to teaching, but his first two teaching jobs, at the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and at the Rectory School in Pomfret, Connecticut, didn’t pan out either.

Turning to graduate work in history, he began classes at Boston College. At the airport one day in the spring of 1984 on the way home to Pennsylvania, he spied one of those LaRouche recruiting tables—the kind with signs that read, feed jane fonda to the whales. He bought his first LaRouche literature—subscriptions for publications that would determine his life for the next decade.

Because of his middle name, as well as his bank account, Lewis was a stellar catch for LaRouche’s fringe political organization. “They paraded him like a blue-ribbon heifer all over the country and all over Europe,” says former LaRouche follower Chris Curtis, who testified at the trial that he had done surveillance for Newbold Smith. “At press conferences he would issue amazing, astounding attacks against his family.” (The Leeburg, Virginia, Loudoun Times-Mirror reported that Lewis once delivered it a press release “claiming that his brother was an alcoholic, that his mother suffered from mental illness, and that his father had traveled to Texas for an expensive ‘sex-enhancement’ operation.”)

“He didn’t have a peer group,” says Dr. Judianne Densen-Gerber, Lewis’s former psychiatrist, who is sympathetic to LaRouche. “They became his peer group.” But at first Lewis resisted their blandishments. He was incensed, for example, when LaRouche people placed fund-raising calls to his parents’ summer house in Maine, and told them to knock it off. But they didn’t. Those who follow LaRouche and his unorthodox conspiracy-haunted theories believe the world is in imminent collapse, and they are under constant psychological pressure to provide the means for Lyndon LaRouche to save it. Usually that means money, especially from the elderly, some of whom have been separated from their life savings by LaRouche fund-raisers.

The world according to LaRouche holds that the Queen of England oversees an interlocking system of worldwide institutional corruption that is responsible for the global drug lobby; that Henry Kissinger is a K.G.B. agent; that B’nai B’rith helped found the Ku Klux Klan; that Zionism is a state of “collective psychosis.” The organization’s great enemy used to be the Rockefeller family, because of its alleged control of the C.I.A. Today it’s the Bronfmans; Lewis is indignant over their control of the Du Pont company, and charges that they are part of an international conspiracy of gangsters and drug smugglers. All H.I.V.-positive people, LaRouche believes, should be quarantined. There are many more astounding tenets of perennial presidential candidate LaRouche’s network of foundations, organizations, and publishing companies here and in Europe, whose members number perhaps 1,000. It is impossible to say, however, whether such bizarre views are far right or far left.

LaRouche’s network is maintained by various security, intelligence, and fund-raising divisions. It is a secretive and closed tribe which often attracts highly intelligent people, who are conditioned to feel a sense of moral superiority, ex-members report. Family ties are often discouraged, says Curtis, who knows women who where made to have abortions by members of the group. “LaRouche once told a conference I attended, ‘Your families are moral pigs.’”

Members hotly deny that they are in a cult, but one woman who spent 15 years close to the center of power of the group says, “There is no question it’s a cult. The thing that defines a cult is that it creates a reality within itself that bears little resemblance to reality outside,” and even when “true” reality impinges, it seems to make “no difference.” The thing to remember, she says, is: “One big kahuna runs the whole show. It’s a shared delusion.”

Lewis Smith, who enjoys a celebrity status in the group, explains that his work is selling expensive subscriptions to LaRouche publications. His former sales-team partner and best friend in the organization, Tony Zito, who recently left full-time work with LaRouche, says that some weeks, working 10 hours a day 6 days a week, the small team would raise $50,000. Zito says he taught Lewis to cook, and they would bicycle for 50 miles at a time. “Inside the organization, we were striving to lead a Renaissance life—the Renaissance ideal, where man is made in the image of God, with divine potential.”

“There’s no forced anything,” says Andrea Diano-Smith. “We just had 10 days in St. Thomas. It’s just ridiculous, the imagery that we are under some kind of guard. I’m not saying it’s not like a rigorous organization, but you can come and go as you like.” Both Lewis and Andrea take umbrage at the idea that LaRouche discourages having children. “We can still be associates of the movement and have children,” says Andrea. “I’m not some kind of doctrinaire LaRouche follower. Neither is Lewis.” Lewis himself says, “If I get tired of this, it’s hasta la vista.”

When I venture to Lewis’s mother that her son seems happy, Peggy du Pont Smith begins to yell on the telephone. “You don’t know anything about this organization! Of course he’s happy. He’s their prized pig!”

In September 1984, Lewis started a promising new job, coaching wrestling and teaching history and English at the Friends’ Central School in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. Students remember that he drove a VW Rabbit, cracked jokes, and talked about beer and girls and the importance of safe sex. But over the course of the school year his behavior changed. His former roommate testified that Lewis was getting bombarded with several phone calls a night from the LaRouche people soliciting his money. His students thought he was an interesting history teacher, albeit a highly unorthodox one. “We never got to World War II, but we learned all about irrigation in Africa,” says Jim Ruttenberg, now an editor at Manhattan Spirit. “He politicized me.” Another student, Chris Bonovitz, says, “He was bringing his political views into the classroom in a real overbearing sense, forcing them on us without prefacing them.”

Parents complained that Lewis was giving their children LaRouche literature. His humor disappeared and, Bonovitz says, he routinely “flew off the handle.” Toward the end of the year, his students realized he was taking LaRouchian Platonic Thought classes far into the night. Bonovitz said he appeared “brainwashed.” Another said, “He wore a khaki suit, and it was obivious he was sleeping in it for a week at a time.… He’d be a mess. I thought he was going through indoctrination.” The final exam was not soon forgotten. Lewis’s favorite student got his blue book back filled with the wisdom of LaRouche. “Remember,” Lewis du Pont Smith wrote, “the world is smothering in a huge oligarchical fart!”

The Smiths were alarmed. What was happening to their sweet child, whom his mother used to call Precious? Over the fall and winter of 1984–85, Lewis and his father would have knock-down-drag-outs about politics when Lewis went over to watch football games. “They were telling him kinky things that were inimical to his family,” says Newbold Smith. “He became a different person,” says his mother.

What really set the senior Smiths off was Lewis’s revelation that he had made a $212,000 loan to help finance the second edition of Dope, Inc., LaRouche’s off-the-wall “expose” of the history of the worldwide drug conspiracy. Lewis told his father he would be getting 16 percent interest on his money, a usurious sum his father scoffed at. A short time later, when his father was on a trip in Scotland, the parents got wind that Lewis was trying to wire $75,000 more to the LaRouchies to set up a wats line. That was when they moved to get a restraining order from the court. As a result of this action, Lewis cut all ties to his family and former friends.

The concrete symbol in the battle for Lewis’s soul is his money, which consists of two kinds of funds. The larger amount—$8 million—is in irrevocable trusts willed to him by his maternal grandfather. He can never touch their principal; he has access only to the interest. The second pile of money—about $2 million or so—is made up of payments from his trusts and other investments, and formerly did not have any strings attached.

When Lewis went home for Easter Sunday dinner in April 1985, he had no idea what was about to unfold, nor did his parents tell him. The next week they filed a petition with the Orphans’ Court of Chester, County, Pennsylvania, seeking the court’s protection of Lewis’s finances by charging that he was mentally incompetent to handle them—that he could, in the words of Pennsylvania’s incompetency law, fall prey to “designing persons.” Thus beginning a massive clash of wills, an internecine battle royal which has gone all the way to the Supreme Court and which continues to this day.

At the heart of this conflict is the issue of proving Lewis’s mental incompetence, a task which so far has entailed a parade of nearly a dozen shrinks, hired by the family, by the court, by Lewis. “The most corrupt, venal, and disgusting humans I ever met in my life,” says Lewis, “were psychiatrists.”

Since this battle was joined, all parties have dug large holes which they’ve then jumped into. Lyndon LaRouche has been tried and gone to jail. Lewis who moved for a few years to Virginia to be near LaRouche, has been arrested for using strong-arm tactics twice at LaRouche recruiting tables at Dulles Airport, and was named in a civil suit for trying to defraud a retired telephone operator of her AT&T stock.

After Lewis and Andrea got married in Rome in 1986, his father’s testimony to prevent the marriage from being declared valid was abruptly halted when Newbold Smith perjured himself on the stand. After denying that he had ever been to Lewis’s house in Leesburg before Thanksgiving 1987, Smith was confronted with a police report which showed that on November 19 of that year he had hired a locksmith under false pretenses in order to gain entrance to Lewis’s house while Lewis and Andrea were away, and that documents of Lewis’s were later missing. In 1988 the family got another warning in the form of a restraining order. The judge was shown evidence by Lewis’s lawyer that the Smiths had hired Galen Kelly to supervise surveillance of Lewis and Andrea in Europe before their marriage. The sealed order barred Newbold and Peggy Smith, Lewis’s two brothers, and his sister from interfering further with his freedom of travel and liberty of association. “Don’t compare father and son,” says Lewis. “This is not a father-and-son tug-of-war of wills. You got a man who is flouting the law. How can you compare that with what I’ve done?”

Lewis and his side have always seen the competency issue as a civil-rights battle in which he is being not just persecuted for his political beliefs but tried for them in Chester County, the “heart of du Pont country,” right on the border with Delaware, the state where the du Pont Family has held sway for more than a century. Thus Lewis is condemned to wear a scarlet I and bear a deep humiliation for “not acting like a du Pont,” says his attorney James Crummet. “In this country, people are allowed to hold kooky ideas.” Crummet is certain that no one else in the United States has ever been declared incompetent for “a mixed personality disorder at least,” which is what judge Lawrence E. Wood ultimately found in Lewis’s case. To be declared incompetent, one must be “mentally ill,” that is, divorced from reality.

Lewis goes ballistic when he hears the name of the psychiatrist his parents hired in the first competency hearing: Dr. David Halperin, who is affiliated with the American Family Foundation, a group antagonistic to cults. “They’re Nazi psychiatrists. They’re part of the network of psychiatrists that trained the Serbian generals who are setting up rape camps to rape women and children in Bosnia,” Lewis shouted unreasonably at me one day. “These psychiatrists were playing games on people the same way the C.I.A. was using LSD for mind control.”

Dr. Halperin concluded that Lewis was mentally ill—suffering from depression and a “schizophrenic affective disorder” that included delusions of grandiosity and persecution and, to a lesser extent, a blunting of emotions and psychological ambivalence. But Lewis’s own two doctors, psychologist Gerald Cooke and psychiatrist Robert Sadoff, said that Halperin was going too far. Cooke felt that, given societal norms, Lewis did not always live up to expectations, but he was not mentally ill “in the sense that term is generally used in the profession.” Sadoff diagnosed a mixed personality disorder, but said, “There was no break from reality at any time.”

Lewis’s lawyers were so confident of the outcome that they waived their right to a jury trial. Big mistake. Said Judge Wood in his eight-page decision issued November 12, 1985, finding Lewis incompetent, “Our own evaluation of Lewis from examining the various letters which he wrote and from observing his testimony is that he has a disorganized mind and compensates by setting up an oversimplified view of the world in which he is one of the good guys and ‘they’ are conspirators bent on mischief. As such he would be and has been an easy target for anyone who pretends to support him in his efforts to combat the bad guys.”

The Wilmington Trust Co., “the du Pont family bank,” as Lewis calls it, chosen over his protests to guard his money, canceled his credit cards without telling him. Instead he received a $ 5,000-a-month allowance, which the judge has allowed to grow to $15,000, or $180,000 a year after taxes. But even today, whenever Lewis wants to purchase anything costing more than his allowance, he has to petition the court, and his family has the opportunity to oppose his request. (In one instance the courts allowed him to buy a baby grand piano but would not give him extra money for piano lessons; said his father, “How do I know it isn’t a LaRouche person giving the piano lessons?”) The judge’s order would not allow him to marry, and in the state of Virginia, where he was residing in 1985, he was not allowed to vote.

In a videotape Lyndon LaRouche made for testimony at one of Lewis’s trials, LaRouche said it was his wife who came up with the idea of Lewis and Andrea marrying in Rome. They say the decision was their own. The two had met one night in an Irish pub in January 1985, when Andrea was 20 and Lewis was 28 and teaching at Friends’ Central. For a month Lewis did not tell Andrea his middle name was du Pont, and Andrea’s mother tells me that at first five-foot-two Andrea thought Lewis was “too tall, too preppy, too old.” Andrea was enrolled in classes in restaurant management and working summers where her father worked, at the Hygrade Food Corporation, a meat-processing plant, where she took samplings from hot-dog vats.

Although Andrea grew up in a tiny row house in a run-down section of South Philadelphia, she enjoyed opera, took piano lessons, and as a teenager studied with the Philadelphia Civic ballet. She went to parochial schools and was basically apolitical until Lewis gave her Dope, Inc. She found it, and gradually Lewis, fascinating. He proposed around Christmas 1985.

Believing correctly that his family would oppose the marriage—the Smiths have still never been formally introduced to Andrea—the two decided to marry in Europe. “I wrote the Pope, and we sought protection from the Church of Rome,” Andrea testified. In October they went to Europe. They had no idea they were being tailed.

The couple made no secret of the fact that Lewis had been declared incompetent. But after appearing in person, they got the necessary documents from the American Embassy to be married civilly in Rome, and a sympathetic Italian priest gave the go-ahead for them to be married in the famed Santa Maria del Popolo church.

Lewis is extremely proud of his wedding pictures, showing Lyndon LaRouche as his best man and LaRouche’s much younger wife, Helga Zepp-LaRouche, as maid of honor. But his face clouds when he describes the honeymoon. “We got one night in a good hotel but the next four on the floor of my mother-in-law’s hotel room, because the Wilmington Trust Co. would not give me any money until I got back.”

When he did return, Lewis asked his mother for the wedding ring his grandmother had willed him. She refused, unless the family could meet Andrea. Lewis said no. He went to Cartier and chose a $31,000 tow-carat diamond, which Judge Wood allowed him to buy over his parents’ objection.

Newbold Smith maintains that he did not oppose the marriage until he found out LaRouche and his wife had stood up for Lewis and Andrea. “That appeared contrived,” Smith says. “Lewis walked out defiantly,” he explains, “leaving his whole milieu from whence he came. Off he went to his new father, Mr. LaRouche. LaRouche and his wife became his new father and mother.”

Being an activist for LaRouche provided more self-importance and more excitement than teaching school ever had. Lewis’s special status within the group has allowed him to run for Congress twice as a LaRouche candidate, in the Democratic primary in 1988 in New Hampshire, and as an independent in 1990 in his home territory of Pennsylvania’s Fifth Congressional District, which then encompassed much of the heavily Republican Chester County, the site of all of his legal battles. The West Chester Daily Local News, published in the county seat, has editorialized that Lewis ought to be considered competent. “Nobody would have questioned his competency if he had given $212,000 to the local G.O.P.,” said a reporter.

West Chester radio-station manager—and J.F.K.-conspiracy buff—Mark Crouch became Lewis’s friend and let him use the phone to buy airtime around the district. “The man was the shrewdest negotiator for advertising time I’ve ever seen—he wants 110 percent for his money.” Crouch scoffed at the idea that Lewis could be incompetent.

Lewis’s losing 1990 campaign, in which he garnered 5,795 votes, is still talked about, and not just because he spent $100,000 of his own funds, which he had to petition the court to get. Lewis’s ads on car radios “caused accidents,” said his Democratic opponent, Sam Stretton. Lewis filled the airwaves with Beethoven and LaRouche conspiracies of “the Anglo-American elite” laundering drug money, and quoted German poet-playwright Friedrich Schiller. “When you meet him he’s a very nice fellow, until you step on or hit the right buttons. This guy goes off.” Stretton remembered a debate on the local radio station in which Lewis “was making very good points, and then suddenly started talking about how Prince Philip was involved with the environmental movement, which was controlled by satanic worshippers. It was fascinating to me. Here was a man who was obviously articulate, but at times he would say things that didn’t make rational sense.”

During the campaign, Lewis was in the middle of hearings to reverse his incompetency status. He had lost all appeals on the first round, all the way to the Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case. But with money no object, and his “state of mind” subject to change, his lawyer James Crummet decided to try again to persuade Judge Wood that he had interpreted the competency statute too broadly. Crummet spent a year and “three or four hundred thousand dollars” researching the incompetency law and hiring several renowned experts to testify on Lewis’s behalf. Crummet felt all was going well until something odd happened. The court-appointed psychiatrist who had examined Lewis changed his original written diagnosis of “personality disorder—mixed type” with “no gross evidence of mental illness” to read, “This condition is a mental illness that affects his competency to handle his financial affairs … rendering him vulnerable to the influence of designing persons.” The revision occurred after the judge, on his own, called the doctor to tell him that he was sending him a letter explaining some expert testimony he hadn’t heard. Lewis smelled a conspiracy and denounced Judge Wood’s “corruption” so vociferously in ads during his congressional campaign that Judge Wood recused himself from the case. Lewis was overjoyed, but Crummet wasn’t. All his work had gone down the drain.

To celebrate, Lewis bought airtime for another outrageous five-minute ad, attacking Wood, the Bronfmans, and the various “corrupt interests” that had made his case a “politically motivated fraud against my constitutional rights of political expression.” His diatribe against the judge ended, “Tonight my wife, Andrea, and I and my political colleagues are celebrating the beginning of the end of the corrupt Get LaRouche Strike Force, which jailed political leader Lyndon LaRouche. We are reciting Schiller’s poem ‘The Cranes of Ibycus,’ which poetically demonstrates how natural law asserts itself, and I am preparing gnocchi Gorgonzola, a dish only a competent human being could prepare and appreciate.”

Said Daily Local News reporter Michael Rellahan, who covered the campaign, “Politically, Lewis is way beyond the point where the streetcar stops.”

With hindsight, it’s not hard to see all the times in this twisted tale when Newbold Smith made the wrong turn. He himself admits as much: “Lewis in the beginning wanted to be part of the family, but I was so determined. I was too much of a mad dog for them.” By reacting so furiously, Smith may well have driven Lewis far deeper into the shelter of LaRouche than Lewis ever thought of going.

The Smiths’ attitude may even have hastened the relationship with Andrea. Martha Diano thinks so. Several times she was contacted by the Smiths to intercede, but she demurred. She says she was incensed when Newbold Smith told her, “Of course, you have nothing to lose.” “I was sure he meant in a monetary way,” says Mrs. Diano, speaking in the kitchen of her small row house. “I told him, ‘Maybe you can afford to lose 25 percent of your children; I can’t afford to lose 50 percent of mine.’ ” She was again infuriated when Lewis’s brother Stockton called and told her Andrea could be raped in the LaRouche organization. “If Stockton had the idea he was going to be speaking to some little old ravioli-maker!” Mrs. Diano says with a huff. “I said ‘What you have done is, you placed Lewis and Andrea in a situation such as the Montagues and the Capulets. They have become Romeo and Juliet.’” Mrs. Diano says Lewis’s parents “cemented the relationship.”

Odin Anderson, Lyndon LaRouche’s Boston lawyer, whom Lewis has also consulted, said Newbold Smith “became an enemy,” bent more on destroying LaRouche than on reconciling with his son. “He became more involved in the partisan effort to undermine the political movement than anything else, maybe thinking the prodigal son would come home, but that’s a terrible misjudgment.”

Like many other distraught parents Peggy and Newbold Smith turned for help to the Cult Awareness Network, the major national group with a full range of services regarding cults. Newbold Smith became a major can contributor, and says it “does God’s work.” The Church of Scientology and Lyndon LaRouche think otherwise, charging that can is nothing more than a referral service for deprogrammers who do illegal kidnappings.

During 1992, according to evidence submitted at the trial, can paid kidnapper-deprogrammer Galen Kelly more than $10,000. He helped prepare a pamphlet on Lyndon LaRouche, says can executive director Cynthia Kisser, and helped her with investigative work on her own lawsuits charging defamation in retaliation for 30-plus lawsuits can faces from individual Scientology members. Some of the money paid to Kelly came from Newbold Smith, but, Kisser declares, “since I have been director—since June 1987—neither I nor my staff have ever taken money from a family to facilitate involuntary deprogramming, nor have we knowingly facilitated in any way criminal acts.” Kisser goes on to say that the world of deprogrammers is a “small, close community.… Frankly, anyone who wants to do something, who’s desperate where a loved one is concerned, they’ll find what they want.”

“If someone’s on a ledge and you climb out to get them to jump back, and at that critical moment you grab them by the hair and toenails and yank them back, is that wrong?” asks Galen Kelly. Judge Ellis apparently thought so. He told Kelly that “under no circumstance is it ever justified to snatch, lift, or pull anybody off the street against their will.” Kelly says he has already been offered a deal by the Justice Department in the kidnapping that went wrong. “If I plead, I get no penalty, just so they can get a conviction,” says the ever defiant Kelly. “I told them to go pound salt.” A grand jury will decide his fate.

Paradoxically, there were times when Newbold Smith, personally or through lawyers, actually called on LaRouche’s hierarchy directly to effect what amounted to a P.O.W. swap: You give me Lewis, I’ll try to help spring LaRouche. Lewis says that at one time his father even offered money through his lawyer David Foulke. Foulke denies the charge. Astonishingly, though, Galen Kelly was Smith’s principal emissary. In 1988, Smith and Kelly had fairly serious negotiations with Paul Goldstein, co-head of LaRouche’s security division, who, according to Kelly, was worried at the time that he would too be prosecuted by the government, and was thinking of setting up a consultancy. “Finally it came down to: You give us Lewis, you can have the Du Pont company as a client,” says Kelly. “It was that crass.” There was a series of meetings in Philadelphia and Washington. The idea, which Newbold Smith testified to at the trial, was to get Lewis to go to work with Kelly in an upstate–New York anti-drug program run by core and its controversial director, Roy Innis. LaRouche would get good publicity for the drug work, and Kelly would have a shot at deprogramming. Kelly says Goldstein wasn’t positive he could deliver Lewis, but he is clear that “Lewis was a pound of flesh absolutely.… They called him Baby Huey. They said he’d be a real problem. They said his wife would be an even bigger problem.” How so? Kelly claims, “She wanted out of the group. She figured she married this Prince Charming—he’s big and rich and good-looking—and what’s she doing? She’s getting petitions signed in the rain in a New Hampshire parking lot.” But the swap was not to be. “We had meeting after meeting,” says Kelly. “Suddenly it broke off.…l The curtain dropped radically and arbitrarily.”

The latest pass at negotiations was made in January of this year. Newbold Smith sent John Markham to explore whether Smith could write a letter to the parole board on LaRouche’s behalf, telling of LaRouche’s efforts to reunite him with his son. Markham, the man who put LaRouche behind bars? I ask. “A lawyer is a lawyer, my dear,” answers Newbold Smith. “Getting access to my son is more important than keeping Lyndon LaRouche in jail.”

Lewis and Andrea suggest that we meet for dinner in a small but chic restaurant in South Philadelphia. Lewis looks strikingly like his father, and is immediately at ease. “He’s got great manners,” Newbold Smith has told me. “They can’t take that away from him—he learned that here at home.” Lewis specifies that the Negronis be made with Stolichnaya, and follows them with pasta and caviar. If these two are in a cult, it has nothing to do with self-deprivation.

But Lewis does feel deprived—of a normal life. Incompetency is such a humiliation that Andrea won’t have children until it’s lifted: he refuses to have his children labeled. “When you’re declared mentally incompetent, you’re disgraced to all your friends.… How can I look my friends in the eye or have any kind of relationship with any self-esteem?” Lewis asks. “It’s a miracle I didn’t go insane. The fact that I didn’t have an emotional breakdown is a testament to my character—not my competence. I hope you’re getting a picture of how enraged I am.”

I ask Lewis what it is about his family that would make this titanic clash of wills so intense. “In the families of the aristocracies, money is not it—it’s bloodlines. My father thinks the du Ponts are upstarts,” alleges Lewis. “My father thinks he’s got bloodlines that go all the way back to William the Conquer’s army. When he married my mother, he believed she was too impure.” Lewis then relates the story that he often heard his father tell of asking for her hand. “My grandfather Henry Belin du Pont told my father, ‘You’re bound to come into a lot of money. The money is family money; it really wasn’t made by any of us. It must be passed down in trust.’ My father sees this as his primary purpose. His role as parent is to ensure that these family trusts are passed down to the next generation … so the ideology of what protects the aristocracies’ bloodlines is safely passed down the corpus of the family money—the Blob.

“My father serves the Blob,” Lewis says. “If I had pursued the life of a ne’er-do-well and invested in racehorses, in yachts, in ski resorts, in fast women, that would have been O.K. the more eccentric and decadent, the better. Because then you’re not a threat to the Blob and the political milieu that controls the Establishment.”

The question that remains is: If the money’s so tainted, Lewis, why soil your hands by touching it?

Lewis says that his father paid “an enormous amount of money” to research that he was a sixth cousin of Diana, Princess of Wales, and that he sent her his book about sailing, Down Denmark Strait. He got a response from a lady-in-waiting. “So did my sister,” says Andrea, pushing her diamond back and forth on her finger. “I think everyone gets a response back from a lady-in-waiting. My sister as a child wanted to be Queen of England. She was a small child; she wasn’t an old man pretending to be related.”

Early the next morning, Lewis gives me a tour of his cavernous house, built in 1858. It’s still undecorated, and largely empty. Andrea stays in bed. In the living room is the baby grand and a cello Lewis is learning to play. He’s also an enthusiastic Italian cook and sells Chinese herbal remedies as a sideline. Of course, he’s also writing a book, which he urges me to read from. It’s not hard to guess its subject. “It is not love that motivates all the cruelty he has heaped upon them,” writes Lewis of his father, “in all that he has done to smother them and to try to brutally force Lewis into the mold that he requires of one who is a du Pont … ” Lewis already has a design for the book’s cover. It is the seal of the United States next to the family crest of the du Ponts. The title is Blood Feud: The Sensational Scandal That Is Rocking the Richest Family in America.

The illustration really should be of two rock-ribbed men on two separate cliffs overlooking the deep chasm between them.

The magazine published a postscript to this article in the December 2008 issue.