This message comes to wake up the jungle.” On Sunday morning, July 20, in Paris, Ingrid Betancourt, the most famous kidnap victim since Patti Hearst, was broadcasting directly to hostages in Colombia’s vast rain forest, an area the size of Texas, where left-wing guerrillas of the farc (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) were still holding between 500 and 700 captives, including 25 political prisoners. Betancourt had been trapped in that jungle—so dense that the ground is completely invisible from the air—for more than six years. On July 2 she had been liberated in a daring rescue staged by the Colombian Army without a shot being fired, and her reunion with her family was carried live on TV. She has had very little time off camera since. Now she was speaking on Colombian Independence Day from a luxe Paris hotel room, dressed in white jeans, a white sweater, and black stacked-heeled mules, with a red chrysanthemum attached to the end of her long, dark braid. On her wrist was a rustic cord resembling a crown of thorns, which she had made from jungle vines for a rosary. Holding a cigarette in one hand, she was speaking on Voices of the Kidnapped, a weekly radio show in Bogotá that broadcasts directly to the hostages, many of whom have radios. “We’re taking your hands, we’re making a chain for you to get out,” she said in her soothing, cultured voice. “Have faith.”

Betancourt, who is 46, was a minor presidential candidate in Colombia when she was kidnapped in 2002. She was also the author of a best-selling autobiography in France, La Rage au Coeur, about her fight as a Colombian senator against corruption and the resulting threats on her life. She was known for attention-getting stunts; she once handed out condoms “for protection against corruption” on the streets of Bogotá. Luis Alberto Moreno, the former Colombian ambassador to Washington, told me, “Ingrid in Colombia was a little flaky, to be diplomatic about it.” Her editor, Bernard Fixot, had specifically marketed the memoir to make her out a heroine, “the new Joan of Arc,” telling her prophetically, “This book will prolong your life.” It was published in English as Until Death Do Us Part. Since regaining her freedom, she has become the object of intense curiosity worldwide, lionized by the French as a cross between Nelson Mandela and Aung San Suu Kyi (the Nobel Peace Prize winner under house arrest in Myanmar) and referred to in the press by her first name only. What was her life like in the jungle?, everyone wants to know. Was she tortured, abused? In a storm of television attention, she intrigued audiences with her reluctance to reveal many details of her years in captivity. She cryptically told Larry King, for example, “Many things happened in the jungle that we have to leave in the jungle.” In France, where she carries dual Colombian and French citizenship and where she studied at the prestigious political-science university known as Sciences Po, she is being touted for the Nobel Peace Prize. On Bastille Day, July 14, President Nicolas Sarkozy awarded her the Légion d’Honneur.

Betancourt was at the hotel to meet Juanes, the Bono of Latin America, and the popular Spanish artist Miguel Bosé, the son of the great bullfighter Dominguín. They were all in Paris for a concert to aid the cause of the hostages and to petition the farc for peace. On the air, Ingrid addressed by name several colleagues still in the jungle. She also had words for the guerrillas: “I speak without rancor. Come back to liberty, come back to reality.” When Juanes sang his song “Sueños,” which opens every broadcast—“I dream of freedom for all who are kidnapped in the middle of the jungle”—Bosé could not control his tears. Ingrid, however, was energized. “We lived for this … summoning song,” she explained to us in the room. She even told how the guerrillas had separated the smokers from the nonsmokers. She seemed almost giddy in her new freedom, barely able to stop talking after years of enforced silence.

From the hotel, I rode with Ingrid in an S.U.V. driven by French Secret Service men to a reception in her honor at the Colombian Embassy, where her mother, Yolanda Pulecio, a former Colombian beauty queen and diplomat in Paris, and her sister, Astrid, who married the former French ambassador in Bogotá, were waiting for her. All three women are made for TV—attractive, camera-ready, media-savvy—as are Ingrid’s children, Melanie, 23, who studies film at New York University, and Lorenzo, 19, who is a pre-law student at the Sorbonne. Throughout Ingrid’s ordeal, top French media advisers donated their services to her family, who organized the Ingrid Betancourt Support Committee. During their 2007 presidential campaigns, Nicolas Sarkozy and his opponent Ségolène Royal both pledged that they would make Ingrid’s release a priority, and her picture hung in city halls throughout France. Meanwhile, her family criticized the Colombian government relentlessly for not doing enough to obtain Ingrid’s release, while adamantly opposing any military action that could bring her harm. Icy notes and protests passed between the Colombians and the French, and the Colombian government still believes that France inappropriately reached out to Colombia’s hostile leftist neighbors, Venezuela and Ecuador, not to mention the guerrillas themselves, in order to secure leverage with the farc.

In the spring of 2003, Dominique de Villepin, then the French foreign minister, acting on a tip from Colombian president Álvaro Uribe that the farc might be ready to release Ingrid, ordered a huge French transport plane to land secretly in Brazil near the Colombian border, where a very sick Ingrid was allegedly being held and where her sister, Astrid, was waiting to meet her. But de Villepin, who had been Ingrid’s professor at the Sciences Po and her rumored boyfriend, did not inform French president Jacques Chirac, or Sarkozy, who was then minister of the interior, or anyone in Colombia of what he was doing. When the plane’s cover was blown and Ingrid did not appear, Sarkozy was apparently furious. Some French officials believe that they were deliberately misled by the Colombians, but President Álvaro Uribe denied that when I asked him. As Pierre Vimont, the French ambassador to the U.S., told me, “Every time we’d come forward, the Colombians did everything to block it.” One Colombian diplomat countered dismissively, “We are frigid Brits compared to the French, [who are] a totally emotional country.” He added, “I have not seen another case where a single person exercised the kind of importance in international affairs that [Ingrid] did. For a kidnap victim to arrive in international politics is unbelievable.”

At the Colombian Embassy, where champagne flowed and roses flown in from Medellín floated in the garden pond, Ingrid was besieged. Melanie and Lorenzo and their father, Fabrice Delloye, a French foreign-service officer and Ingrid’s first husband, who had fought hard for her release, did not attend the reception. Ingrid’s second, Colombian husband, Juan Carlos Lecompte, had not been with her since her rescue. The children joined their mother halfway through the ensuing concert at the Place du Trocadéro, across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower, where Ingrid was honored onstage, this time by Sarkozy’s opponent Bertrand Delanoë, the Socialist mayor of Paris, who draped the Colombian flag over his shoulders as if to indicate that Sarkozy and his right-wing government could hardly love Ingrid more than the Socialists did. Sophisticated Colombians observing the scene, such as Roberto Pombo, the editor of El Tiempo, Colombia’s New York Times, and Fernan Martinez, Juanes’s manager, were highly amused by the sudden turnaround of Colombia’s image in France. “Nobody knew where Colombia was, or they thought we were all drug dealers,” Pombo said. Ingrid, in her speech, switched easily from flawless French to Spanish, and she and other speakers called again and again for liberty—libertad. Suddenly she stopped, as though she sensed that there really was no more to say. Gracefully thanking the mayor and his country—”Merci, Bertrand. Merci, la France“—she paused, turned toward the band, and ordered, “Music, maestro.”

A Hostage’s Memories

The ceremonies in Paris were a far cry from forced marches in the Colombian jungle, where Ingrid was chained to a tree for a year. At one point, she was so overcome by despair that she stopped eating. In a “proof of life” photo of her released by the farc last February, she looked so frail that people were shocked to see how healthy she appeared at the time of her release. It is now clear that she is a courageous and canny survivor, and that throughout her captivity she had male friends who protected her.

Luis Eladio Pérez, the 55-year-old former senator from the southern Colombian state of Nariño, a married father of two, became Ingrid’s closest confidant in captivity. A gentle man with pouches under his hazel eyes, he had been captured eight months before she was, in June 2001. His guards were not permitted to talk to him, and the stress of his solitude was so great the first year that his face began to freeze up for lack of speaking. He routinely slept during the day and stayed awake at night, listening to the racket the insects made during the early evening and then to the news on a small radio the guerrillas allowed prisoners to have in order to prevent suicide or insurrection. Hearing occasional messages from his family and knowing that his wife was fighting for him were the only things, he claims, that kept him from attempting suicide. “I have a terror of the dark,” he told me in Bogotá, where he now resides. Even today, he added, “around 6 or 6:30 p.m., when it starts to get dark, I get nervous.”

In August 2003, Pérez met Ingrid Betancourt and Clara Rojas, her campaign manager, who was two years her junior and who had been kidnapped with her. The two women were not getting along, he said, and eventually they had to be kept in separate tents. For months, however, they and Pérez and four other political prisoners shared a crude jail approximately 8 feet by 14 feet, with barbed wire on the walls. In October 2003, the Colombians were joined by three American employees of the defense contractor Northrop Grumman—Thomas Howes, Marc Gonsalves, and Keith Stansell—who had been captured after their plane, from which they were inspecting the results of efforts to eradicate coca crops, crashed. The Americans, who spoke no Spanish, had only the clothes on their backs when they arrived, and they gave off a powerful body odor that the Colombians found repulsive. All 10 slept on wooden bunk beds with nothing but plastic sheets and mosquito netting. “Do you remember the Nazi jails from World War II?,” Pérez asked. “They were exactly the same.”

At least the structure had a crude shower and a toilet, Pérez said, with water pumped from the nearby river. At no other time in his nearly seven years of captivity, in various camps, was that the case. The prisoners’ diet of rice, broth, vegetables, and occasional meat was cooked by their guards. The food was delivered by convoys of vehicles that had crossed hundreds of miles of jungle on roads constructed of wooden planks and over makeshift bridges anchored by oil drums filled with cement. This immense area, which covers 51 percent of Colombia, is virtually uninhabited, with less than one person per square mile. For centuries the government made no serious effort to control this crucial “green lung” adjoining the Amazon. The farc move their troops and weapons with relative impunity over an intricate ad hoc highway system in the latest pickups and four-wheel drives (known as “motor rats”), the same vehicles they use to transport the coca-leaf harvest and the cocaine paste produced from it.

The drug traffic is destroying the eco-system as more and more areas have to be cleared because of fumigation, and as the rivers get more and more polluted from the chemicals used in the cocaine labs. The farc not only levy a tax on the farmers who grow the coca but also often set the price of the refined cocaine to distributors, and thus grow richer and richer. During President Andrés Pastrana’s term of office, beginning in 1998, the farc were ceded a territory the size of Switzerland as a demilitarized zone from which they could conduct negotiations with the government. In 2002, however, Pastrana, realizing that the farc had no intention of negotiating peacefully, revoked his decision, and the Colombian Army had to fight many battles to reclaim El Caguán, as the area was called. As a result, guerrillas guarding prisoners there were considered especially tough.

Daily life among the hostages often came down to petty resentments. “Ingrid Betancourt is someone who generates a lot of envy,” Pérez writes in his best-selling book, the title of which translates as “Seven Years Held Hostage by the farc.” “She told me that was part of her karma since she was in school.” Fellow prisoners were angered that most of the news was about her, “as if the rest of us did not exist.” Even her kidnapping was considered suspect. She had been warned repeatedly not to go into the area in southwestern Colombia where she was seized. Her bodyguards had been ordered not to take her there, because it was too dangerous. The army stopped her at several checkpoints to advise her to turn around, but still she persisted. A prevailing opinion among Colombians in the know is that she deliberately put herself in harm’s way to gain publicity for her campaign, never dreaming that she would be detained long. Ingrid says that she had an appointment she could not miss, with a mayor in a nearby town who supported her candidacy, and that she did not get a helicopter she had been promised. In Paris during her media circus in July, Alonso Salazar, the mayor of Medellín, told me, “Colombians greeted her with an extraordinary outpouring of support—she became the symbol for all hostages. But silently they blamed her for taking the risks she did in her political life—going into that area knowing the danger.”

Ingrid stood out in the jungle. Sophisticated and well traveled, she exercised vigorously to keep herself fit. She was clearly from a privileged background; her father had been the ambassador to unesco in Paris and a prominent educator. While the other prisoners played cards or talked among themselves, Ingrid gave classes in French. However, Pérez writes, “Her worldliness and store of knowledge generated more resentment than admiration.” She was soon in a class struggle, not only with the female guards, who were generally chunky and unattractive, but also with her fellow prisoners, which was ironic, since she had always considered herself a radical reformer. “So in the drama of being held hostage you had to add a very tense environment, which was not beneficial to anyone,” Pérez writes. “The monotony was as dangerous as the tigers,” he told me. Once, Pérez and another friend of Ingrid’s were physically attacked by other hostages for sticking up for her. Most of the time, however, Ingrid could take care of herself. Pérez and John Pinchao, another prisoner who escaped and wrote a book, both recount instances when men made unwanted advances toward Ingrid; she slapped a guerrilla across the face and kicked a fellow hostage in the testicles.

Like many men, Pérez was captivated by Ingrid. A Colombian official who had worked with her after she left her young children behind with their father in New Zealand and moved to Bogotá to enter politics told me, “Ingrid wore sexy miniskirts and used her good looks, which made the other women in the ministry very angry. She is a very attractive woman, and with her wit and audacity she can get a man who is a bit naïve to dance any way she wants.”

In 2005, Ingrid urged Pérez to join her in an escape attempt, which failed at the end of six days, when they ran out of food and Pérez—a diabetic, whose feet gave out—could go no farther. They were picked up only a short distance from where they started, and the guerrilla commander told them that, owing to Ingrid’s high profile, if they had succeeded in getting away, all the guerrillas guarding them would have been killed. For the next year, Ingrid and Pérez were chained to trees, and the chains around their necks were removed for only half an hour a day, so that they could bathe in the nearby river. They were also deprived of shoes, and jungle rot set in. Pérez managed to make plastic covers for Ingrid’s feet. Only today are his own toenails growing back.

They were allowed to speak for just one hour a day. Many of those hours they spent devising a 190-point program to address the social ills of Colombia—“the poverty, misery, lack of education, and despair that gave rise to the guerrillas in the first place,” Pérez told me. “We worked on it four or five years. What we thought should happen in Colombia to get peace.” They have plans to start a movement based on the program, he said, “after we have had time to recover a bit.”

In July 2007, Ingrid and Pérez were separated, and he was taken, along with several Colombian officers and the three Americans, to another part of the jungle. Pérez’s last six months before his release, last February (five months prior to Ingrid’s rescue), were the worst. He was chained by the neck to Thomas Howes, with only 15 inches of chain between them. “We had to walk together, go to the bathroom together, bathe together, eat together,” Pérez said. “I had to know everything—his snores, his odors.” They ended up good friends. “We had to help each other endure it; if not, we would have killed each other.” Pérez believes that Howes saved his life. “I had a heart attack, and he gave me the one aspirin he had saved,” he said. “Do you believe it helped?,” I asked. “I am here with you,” he answered, adding, “Do you remember the story in the Bible about the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes? Well, this was the multiplication of the aspirin!”

The Other Captive Women

Unlike Ingrid, who resisted the guerrillas’ advances, Clara Rojas, her campaign manager, slept with the enemy. Guards were strictly forbidden to have sex with prisoners; they were not even allowed to have children among themselves. If a farc woman got pregnant, she was supposed to abort. According to one account, after Rojas wrote to someone high up in the guerrilla forces and asked for permission to have sex, she received a box of contraceptives. Pérez suggests that Rojas felt her biological clock ticking and resolved to have a baby, at the same time figuring that giving birth might get her released sooner. When I spoke to Rojas in Bogotá in August, she said she had not had “any expectation” of being released early as a new mother. When I asked her, “Was it your decision to become pregnant in the jungle?,” she answered, “That is a difficult question. But, given the fact I had to assume responsibility, I wanted to save the life of my child. As we say, don’t cry over spilt milk.” With regard to the father of the baby, she said, “I don’t have information.” (Pérez in his book says a farc commander told him and others that a guerrilla had been executed for having relations with Rojas.) A number of Rojas’s fellow prisoners were highly critical of her, even to her face.

For the last couple of months before the birth of the baby, a boy named Emmanuel, in April 2004, Rojas stayed in a separate shelter. She requested a doctor and the Red Cross, but she was refused. The Cesarean birth turned into a nightmare. Rojas was attended by a male nurse and her principal jailer, the farc commander Martín Sombra, who is now in jail himself, in Bogotá. She was given anesthesia, she told me, but she woke up before the operation was completed. “It was horrible,” she said. The nurse had cut her open crudely and had broken the baby’s arm while trying to extract him. Since there was no plaster of Paris to set the bone, Rojas said, “they put a bandage on it, but it wasn’t enough.” For months Emmanuel howled in pain, and he was allegedly drugged to make him stop crying. Rojas suffered postpartum depression. “I was so weak,” she said. “To have your first child while kidnapped—what a disaster.” Her fellow hostages have reported that because she was not a natural mother—she gave the baby boiling-hot milk, for example—the farc turned him over to a female guerrilla, who let Rojas see him only through the barbed-wire fence. “They took the baby away,” Rojas told me. “I was not allowed to keep him permanently.”

In the fall of 2004, the farc told the prisoners that they were all being moved. They set off on a long march through the jungle, chained to one another and guarded by guerrillas on either side. They slept in hammocks in order to avoid contact with the dangerous snakes and insects on the wet ground. Ingrid, who had once had hepatitis and was suffering from a liver disease, had to be carried. There was concern that Emmanuel’s cries would alert Colombian soldiers patrolling the area, and when the march ended, in October 2004, the guerrillas handed the baby off. Rojas did not see him again for three and a half years. Upon her release, she was supposed to be re-united with Emmanuel, but the farc could not find him. Using intelligence sources, the Colombian government located the boy living under the auspices of a social agency in Bogotá. The villager to whom the farc entrusted the baby had passed him on.

There was also another grieving mother on that march, Gloria Polanco, the wife of a senator and former governor, who was kept with Ingrid, Rojas, Pérez, and the three Americans. She had no idea whether her two teenage sons, who had been kidnapped with her, were dead or alive. They had all been snatched from their beds in the middle of the night in 2001, when guerrillas dressed as policemen entered their apartment building and kidnapped 15 people, ranging in age from 15 to 60. Polanco’s husband, Jaime Lozada, was in Bogotá at the time. The farc separated the boys from their mother. “They took them into a truck and into the jungle,” Polanco told me. She did not see them again for almost seven years. After three years, their father paid a ransom, and the boys were released. Not long after that, Lozada was shot to death while driving with one son, who was wounded. Recently, a guerrilla in prison confessed to the murder but said he had meant to kill another man. He asked forgiveness of Polanco and her family, on Voices of the Kidnapped, and she gave it.

“Even though I was so abandoned, I felt the presence of God,” Polanco said, sitting in an outdoor restaurant in Bogotá, where she chain-smoked and stared at me with incredible sadness. She was elected to the Colombian Congress in absentia in 2002, and she credits her faith for keeping her sane. “I spoke to God a lot. I could feel His suffering,” she said. “You could see the difference between those who had faith and those who didn’t. Some prayed a lot, and some said that God didn’t hear them.” Polanco’s daily routine consisted of an hour and a half of calisthenics, beginning at five a.m., an hour and a half of prayer, a bath in the river in her underwear whenever possible, several hours for washing and mending clothes or playing poker—whatever she could do to keep occupied. Ingrid, who she said was a good friend, gave her French lessons. She told me that when she and Ingrid were together they never had problems with sexual harassment: “You could be strong and fight them off.” As for the farc guards, “We didn’t have any time with them—they were always far away.”

Polanco has no job and receives no help from the Colombian government other than bodyguards to protect her. Like some of the other released hostages, she has received death threats. “I have to be both father and mother. My sons lost three years of school,” she said. Try as she might to conceal her feelings, she showed traces of bitterness toward Ingrid. “Let’s not forget to be realists,” she said. “Let’s not make symbols and icons out of women who aren’t.” Putting her hand on mine, she said, “I was the one who suffered the most. I was almost totally destroyed.”

A Bloody History

Tirofijo—Sureshot—was the nickname given to the founder of the farc, Manuel Marulanda, who died last March at 78 of natural causes. The farc’s Ho Chi Minh, he fled to the mountains to found the rebel group about the same time in the 1960s that I, as a 21-year-old Peace Corps volunteer, moved into a poor barrio on the outskirts of Medellín. Che Guevara was still alive. Revolution was often discussed among the young, but only theoretically. Peace Corps members experienced firsthand the endemic social inequality in the country and the passivity of the poor, who were basically taught that their poverty was God’s will and that they would be rich in heaven. Colombia was very Catholic then, not yet tainted by the tremendous wealth and corruption cocaine would bring to it. Most of the elite in Medellín—which is still the business capital of the country—had gotten rich by working hard and building companies.

I had a Colombian boyfriend, Alfonso Ospina, a dashing, six-foot-four scion of a leading political dynasty and the son of a very rich cattle rancher. His self-made father, Bernardo, was the first cousin of his mother, Elena, who was the daughter of a Colombian president, Mariano Ospina. In his youth, Bernardo had gone on horseback into the jungle north of Medellín for a year at a time, to open up huge territories along the Magdalena River from Medellín to Monteria, a small city 175 miles away, which has since become notorious as the headquarters of the paramilitaries who rose up in response to the cattlemen asking for protection from various guerrilla bands, including the farc. In time, both the farc and the paras would evolve into little more than murderous, non-ideological drug traffickers.

I worked with a mountain community above my barrio—where coffee, flowers, and vegetables were grown—to build its first school. The National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia helped us with materials, and the community provided the labor. When we inaugurated the two-room schoolhouse for 35 children, in 1966, the community named it the Escuela Marina Orth. In 2004 the secretary of education in Medellín asked me to help make it the first bi-lingual public school in Colombia. I started two foundations to raise money, and today 350 students are enrolled. It is the first school in Colombia to have computers from the One Laptop per Child organization. For many years I was unable to visit the school because of the violence that had overtaken Medellín, starting with the attempt by the notorious narco-trafficker Pablo Escobar to control the area, which he almost succeeded in doing, killing more than 400 police officers and winning the support of many of the poor. Escobar hid out right near my school shortly before his death, in 1993. Then the area became favored by the paramilitaries, who also dealt drugs, kidnapped civilians, extorted money from businesses, and generally cowed the local population.

After leaving the Peace Corps, I remained close to people in my barrio, as well as to Alfonso, who went into politics. In the early 80s he was chief of staff to President Belisario Betancur, who reached an accord with the farc for a cease-fire and the creation of the Patriotic Union Party, which allowed leftists for the first time to play a role in government. So many of its candidates and members were murdered, however, by the paras and right-wing death squads that the whole process broke down irretrievably. I will never forget President Betancur telling me in an interview in Bogotá in 1981, before cocaine really took hold, “We would not have these problems if you [Americans] were not such excellent clients.”

In 1982 the farc made the formal decision to adopt the drug trade as a way to finance its activities. Cocaine is used by the farc to purchase weapons and feed its army. Colombia’s minister of defense, Juan Manuel Santos, told me, “Every time I go to Washington or New York or London or Madrid, I say, ‘With every snort you’re killing somebody, you’re committing ecocide.’ ” He echoed President Uribe, who said, “If not for illicit drugs we would have defeated these groups long ago.” The sad truth is that too many Americans are blithely indifferent to the connection between using cocaine recreationally and the bloodshed and environmental destruction its use causes in Latin America.

One of the ways for big narcos to launder drug money was to acquire land. Their fincas and haciendas became symbols of their wealth. In the late 80s, Alfonso Ospina refused to sell a large piece of his land to a leading paramilitary chief, who also wanted a percentage of his cattle business in return for providing him with “protection.” By then Alfonso was a senator from Medellín. He was kidnapped on his way to work one morning in 1988, and months later his family learned that he had been murdered. His kidnappers, hearing gunshots fired by one of their guards, had believed that Colombian soldiers were coming after them. They ordered Alfonso to run and shot him in the head. After paying a reward of $200,000 for his body, his family received a map showing where it was buried.

In 1990, one of the first terrorist bombings occurred in a public place in Medellín, at a popular restaurant owned by a friend of mine, which was a gathering spot for businessmen and politicians. In the 90s, the farc and other guerrilla bands took to stopping whole strings of cars on highways in order to pick out the people who would bring the largest ransom. Meanwhile, in the cities, drug dealers and their molls held sway to such an extent that, over the years in the poor comunas, the look of young men and women has changed from simple and modest to gangsta-rap tough, and so many women have undergone breast-enhancement procedures that Medellín is referred to as Silicone Valley. People commonly tell stories of escapes and near misses, of family members gone bad, that seem right out of a Gabriel García Márquez novel. “Everybody thinks that Márquez invented magical realism,” Jorge Mario Eastman, President Uribe’s communications adviser, told me, “but he just writes down what really happens here.”

No one goes unscathed. Juanes, the singer, has had a cousin kidnapped. President Uribe’s own father was kidnapped and killed. According to former Colombian ambassador Moreno, “He wants to liberate Colombia from the pain he felt about his father.” Colombians have experienced so much mayhem in the last 40 years that the city dwellers, especially, have almost become inured to violence. Annual murder rates in Bogotá and Medellín are now lower than in Washington, D.C., thanks to Uribe, who has aggressively pursued “democratic security” and has made the roads in most of the country safe to travel again. As a result, he has earned a 78 percent approval rating (it was 90 percent right after the hostages were liberated). If the dramatic rescue of Ingrid Betancourt, 11 soldiers and policemen, and three Americans by the Colombian military did one thing, it was to make Colombians not only proud of their country but also ready to fight back.

Bad Neighbors

When the big, white, Russian-made MI-17, the Hummer of helicopters, touched down on the savanna in Guaviare Province, in southeastern Colombia, on the morning of July 2, it looked just like the ones that Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez had sent to pick up Clara Rojas and congresswoman Consuelo González in January, and Luis Eladio Pérez, Gloria Polanco, and two other politicians in February.

Chávez, the fiery leftist autocrat who hates the United States and has designs on ruling the whole northern region of Latin America, has always been tight with the farc, which is officially designated a terrorist organization by the United States and the European Union. But just how closely Chávez and the farc were aligned was not clear until last March, when an amazing trove of intelligence came into the hands of the Colombian government. After the Colombian Army went one mile into Ecuador to raid the camp of senior farc commander Raúl Reyes, killing him and 33 other people and wounding 190 more, it seized three laptops, two hard drives, and two memory sticks, which together contained 8,736 Microsoft Word documents, 211 PowerPoint presentations, and 2,468 other documents. Manuel Marulanda, it turned out, had sent all messages to his farc commanders and fronts everywhere through Reyes, who served as the farc’s worldwide communications director. “Imagine a chief of staff who directly passes all the communications of the president to his ministers and to his embassies around the world and decides to keep a record. That’s going to be pretty rich,” said Assistant Defense Minister Sergio Jaramillo, who is in charge of the confiscated computer data, the authenticity of which has been verified by Interpol. “Reyes felt so safe in Ecuador he didn’t even bother to encrypt.” As a result, Jaramillo continued, “you understand their thought processes, where they are coming from.” He showed me sample documents, including pictures of the 19 people the farc had working for them abroad—one of them an American professor. Some of them have since been arrested.

The computer files revealed that Chávez had sent Amilcar Figueroa, one of his top-ranking officials, to China in November 2006 to buy arms for the farc, and had offered the farc up to $300 million worth of gasoline to sell along the Colombia-Venezuela border, where Venezuela tolerates farc encampments. Other documents showed that Marulanda, apparently in need of cash, had wanted to set up a farc fund of $230 million and that Chávez had pledged almost that exact amount. “That was one of the surprises,” said Jaramillo. “It looks like they need money.” The farc had made an offer of uranium to Chávez, presumably to be passed on to Iran, but it was not of good quality. These disclosures were sufficiently damning to cause Fidel Castro himself to step in and tell Chávez to clean up his act.

But Colombia is not able to count on its neighbors. According to the seized material, the leftist government of Ecuador, which, like Venezuela, is very anti-U.S. and anti-Uribe, was also “actively aiding and abetting” the farc. This past September, Chávez recalled his ambassador from Washington and ordered the U.S. ambassador to leave Caracas. Bolivian president Evo Morales, Chávez’s ally and former head of the coca growers’ union, booted the U.S. ambassador out of La Paz. The Bush administration, fueled by the Reyes files, promptly accused three top Venezuelan officials of supplying the farc with arms and helping them to traffic cocaine. Without question, the Reyes files and the hostage rescue have seriously damaged Chávez.

Fooling the farc

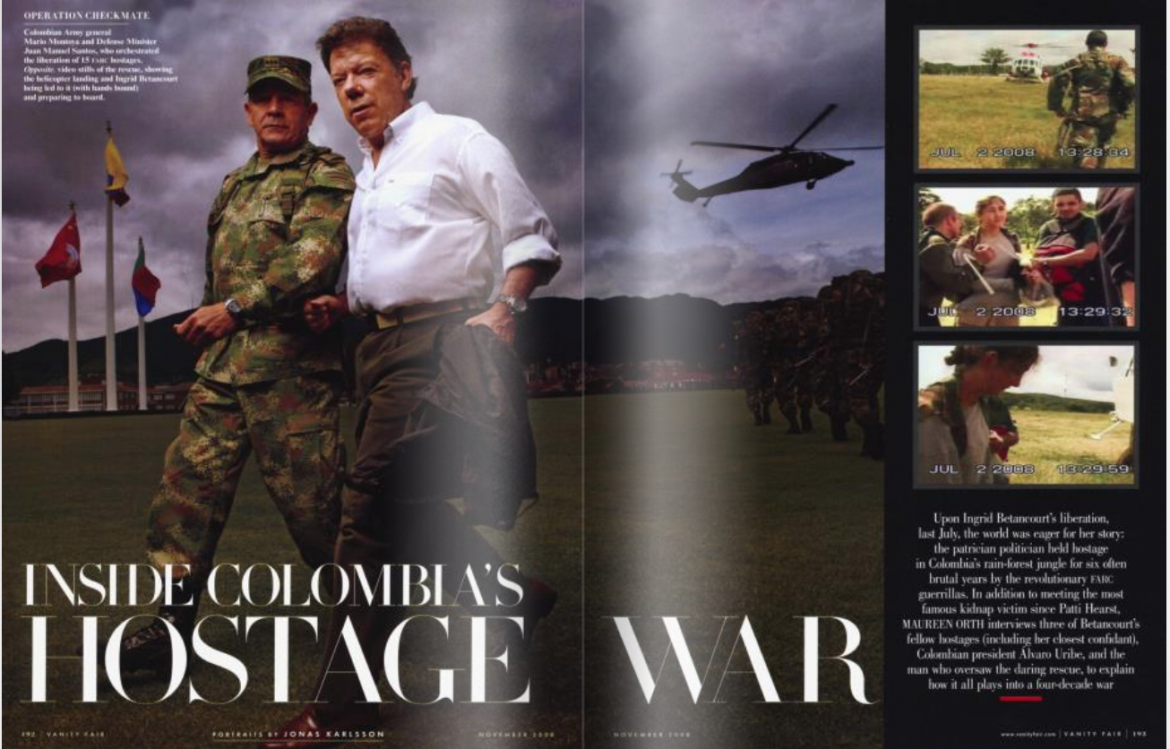

Operation Jaque (in English “check,” as in checkmate) was conceived by Colombian Army officers and members of military intelligence who had penetrated the highest command centers of the farc. After the death of Marulanda and the appointment of a new head commander, Alfonso Cano—who unlike his predecessor has a university background—the organization’s governing secretariat was experiencing internal tensions. Jaque was so secret and compartmentalized that only a few people knew all the details. The idea was to trick the farc into believing they were handing off Betancourt and the other prisoners to unarmed humanitarian workers, who would deliver them to Cano’s command headquarters and negotiate for a peaceful exchange of guerrilla prisoners.

For several months Colombian commandos had known that they were zeroing in on the hostages. On February 4 they had seen at close range the three captive Americans bathing in a river. These elite troops had been trained by American Green Berets, some of whom had patrolled the jungle with them. One American soldier told me that the jungle terrain was so hard to navigate that “I’m out there wishing I’m in Afghanistan.” There had been several previous attempts to rescue the hostages. In 2006, for example, a rescue mission had been mounted to get the Americans out, but they had not been where they were supposed to be. Moreover, President Uribe had promised President Bush that he would not put the Americans in harm’s way.

The farc secretariat does not speak directly to outlying commanders, but its orders are usually issued by the same radio operators, so intelligence agents in Colombia, according to Defense Minister Santos, “know by heart who’s speaking.” By the start of 2008, the Colombian Army had penetrated the farc’s communication system and broken their codes. “We had been listening for years,” one American told me, “but suddenly they started talking back.”

It was a strictly Colombian operation. The Americans contributed by supplying backup aircraft equipped with satellite communications and the latest tracking and eavesdropping equipment. Ironically, for years the U.S. had played no part in freeing hostages or capturing members of the farc, because American aid—administered principally through the controversial Plan Colombia, which has disbursed more than $5 billion in the last eight years—was committed exclusively to fighting the war on drugs. However, once the three American contractors were taken prisoner, in 2003, U.S. policy shifted and went after the farc.

The nine commandos and five pilots involved in Jaque had all taken acting lessons and had received scripts to memorize—not only so that they would be credible at the scene of the rescue, which was timed to last seven minutes, but also so that in the event of their capture they would have fictitious life stories to tell the farc. (A second helicopter, with pilots similarly equipped with fake life histories, was at the ready in case of an emergency.) American military personnel wired the Colombian pilots’ helmets so that they could broadcast their progress directly, using coded language, to the American aircraft hovering above, out of sight.

The plan had not been an easy sell. According to Santos, Colombia’s head of intelligence had declared, “This is absurd. It can’t be done.” But the officers persisted until they finally convinced Santos, in May. He said one of them told him, “ ‘Minister, you are very much aware of, and afraid for, the lives of the hostages, but this is virtually risk-free. If they catch [on to what we’re doing], they simply won’t be there. If they catch us during the operation, the ones at risk are us. They’ll probably shoot us on sight, but we are unarmed, so there is no reason for them whatsoever …’ I said, ‘My God, you’re right. Go ahead and give me the proof that the fish is on the hook.’ ”

The farc took the bait so readily that the operation had to be moved up 13 days. A group of guerrillas marched the three Americans from one locale, while others brought Ingrid Betancourt and Colombian Army corporal William Pérez—her latest protector, who had forced her to eat by spoon-feeding her—from another. A third group of hostages was made up of police officers and soldiers. They were all brought—some from as far away as 60 miles—to the designated gathering spot. Two guerrilla commanders were in charge, Gerardo Aguilar Ramírez, known as César, and Enrique Gafas. Without realizing it, César had been following the Colombian Army’s orders since the beginning of May. “If you have them on the hook, you have to reel them in quick,” Santos said. “Otherwise, they’d go away. The risk factor was time.”

Santos had to get approval from President Uribe, who said the minister would have to abide by his promise to President Bush not to use force. Santos had briefed the American ambassador and the C.I.A. station chief in Colombia a week earlier. “I had them come to my house,” Santos said. “They were stunned.” The C.I.A. chief told him, “My hat’s off to you.” The American ambassador, William Brownfield, said that he would have to brief the Pentagon and the White House. On Friday, June 27, National-Security Adviser Stephen Hadley was briefed, and on Sunday, June 29, Vice President Cheney had his briefing. It so happened that John McCain was on a visit to Colombia on Tuesday, the day before the rescue was set to take place, so he was also told about it, but he had nothing to do with the operation. According to someone close to the situation, Brownfield was grilled by Washington, especially about the planned role-playing, but he said he knew the officers involved and was convinced they were “sound.” The Americans signed off.

Santos told me he knew that “God was on our side for two reasons.” First, César asked to bring six additional guerrillas onto the helicopter, but the 9 fake humanitarian workers, 15 hostages, and César and Gafas added up to 26, which was the maximum number the helicopter could hold, so César was easily denied. The 38 guerrillas on the scene remained on the ground unharmed.

Second, that weekend Noël Saez and Jean-Pierre Gontard, the French and Swiss delegates, respectively, in touch with the farc, had coincidentally arrived in Colombia and asked for permission to go into the jungle to look for contacts with the farc in order to explore a humanitarian mission, an exchange of hostages for sick or wounded farc members, which Uribe had long resisted in his determination to defeat the guerrillas once and for all. Santos did more than just grant the delegates permission. “I leaked it to the press on Sunday, because that would confirm our story, our novel. The guerrillas would hear it on the radio, and we had told them that this was a transport to Cano, because we were going to start negotiations about humanitarian exchanges. The presence of these two guys was a gift from God.”

“Almost Perfect”

If anything went wrong, there was always Plan B. If the guerrillas fled altogether, there were 39 more aircraft hovering nearby, and between 400 and 500 Colombian soldiers, ready to form a cordon around “the places where these people could escape,” Santos said. “You would stay far enough away for these people not to feel attacked, but near enough not to let them escape. That was Plan B.”

On the morning of July 2, Santos called the bishop of Bogotá and asked him to pray “for something very special.” When the helicopter landed, the pilots were wearing T-shirts emblazoned with Che Guevara’s image. The first soldier out of the helicopter was wearing a Red Cross bib, which was against the rules of the Geneva Conventions. He later lied to his superiors, swearing on the life of his son that he had put it on at the last minute because he was scared. His alibi was blown when an unauthorized documentary of the whole operation—comprising insider video and still photographs—aired on Colombian TV. (CNN had been offered the documentary earlier, for $300,000.) Apart from that transgression, the operation—which took 22 minutes—was deemed “almost perfect” even by the farc’s lawyer, Rodolfo Rios. He told me that the farc also objected to the fact that two of the commandos had posed as journalists, wearing vests with Venezuela’s Telesur TV logo on them. While the hostages were being loaded onto the helicopter, those two distracted César by begging him for an interview. The commandos later threw César and Gafas—who were handcuffed, kicked, and given a sedative, according to their lawyer—into the front of the helicopter, and they took off. Once in the air, the fake reporters caught on film the jubilation expressed by Ingrid, the three Americans, and the other prisoners once they realized they were really free.

The farc are now into their third generation. The group was founded in the 1960s by the “historics,” peasants in the eastern cordillera of the country who adopted their Communist ideology from the Russians, casting it in the old Soviet mold, intensely bureaucratic and intransigent. They were succeeded by Marxist-Leninists who had little interest in winning over the general population, partly because they didn’t need to, since they could support their cause with drug money. Today, according to Alejandro Santos, the editor of Semana magazine, the Newsweek of Colombia, and a cousin of the defense minister, the farc are dominated by people who have grown accustomed to taking easy drug money for granted. “This war is like Frankenstein,” he told me. “It has a revolutionary beard, its pockets are stuffed like a drug dealer’s, and it has the soul of a terrorist.”

If you consider how geographically challenging Colombia is, with two oceans, three mountain ranges, and 200,000 square miles of jungle, you get some idea of why the farc are so hard to defeat. Dr. David Spencer, of the National Defense University, in Washington, D.C., is perhaps the leading expert on the farc outside Colombia. By the late 90s, he told me, “they controlled an area the size of France.” At the end of 2001, they had 16,000 men and women in arms, controlled 70 percent of the Colombian countryside, and were stealthily gaining a stranglehold around Bogotá.

During that time the farc became fixated on gaining “belligerent status,” an obscure term defined by the Geneva Conventions. “It means you have reached such a level in your war that, even though you are not a government, you are recognized to be able to import and export arms, open embassies, to act like a government,” Spencer explained. The only requirement for belligerent status that the farc did not fulfill was being capable of engaging in prisoner exchange. “So they captured 500 soldiers to raise the ante, to make it valuable enough to the Colombian government to give them belligerent status by forcing the government into a political corner,” Spencer said. When that did not work, “they started kidnapping politicians.” The country suffered from the violence, with 4,000 kidnappings in 2000 alone. Álvaro Uribe, according to Spencer, was “the man on the white horse,” elected in 2002 to change all that.

Man with a Mission

‘I am 56 years old,” President Uribe told me, “and during my generation, we have not lived a single day in peace. Therefore, for the coming generations we have the right to fight, to preserve for the future the new policies that produce good results for this country.” Uribe is a small, very intense man, a Harvard graduate who sleeps little and flies all over the country, micro-managing wherever he goes. He is so revered that when Ingrid Betancourt, after her release, ventured to remark in Paris that Colombia had adopted a “radical” view toward the guerrillas, her popularity “fell 20 percent in 24 hours,” according to Enrique Santos, the editorial-page editor of El Tiempo. One day in August, I flew in two helicopters and on the presidential plane with Uribe as he inspected two major tunnels under construction. He went five miles inside the second tunnel on a little train the miners use, and he took a group of us reporters along. Back on his plane, he disappeared. “Where did he go?,” I asked. “Oh, he’s probably doing his yoga,” one of his aides said.

Uribe’s platform of democratic security has been extremely successful in diminishing the farc’s numbers, now estimated at between 7,000 and 9,000. In 2002 the army mounted Plan Patriota, a campaign to beat back the guerrillas, first from around Bogotá and then, over time, in their stronghold in the southern part of the country. Many argue that the war on drugs, with its aerial fumigation and manual eradication, makes the campesinos who grow coca the natural allies of the farc. Many human-rights groups fault Uribe for failing to curb abuses in the army and for being too soft on the paramilitaries. Those same groups have prevailed upon the U.S. Congress to keep Colombia from receiving free-trade status—a very sore point with Colombians.

Uribe responds, “When Plan Colombia began, this country was almost a failed state. During these eight years Colombia has made significant progress.” He ticks off impressive gains made in the number of people covered by health care, the number of people in vocational training, and the number of university graduates. “In other Latin-American countries there were guerrillas against dictatorships. Here we have terrorists against a democratic state.” When I reminded him that Colombia is No. 3 in terms of social inequality in South America, behind Brazil and Argentina, he said, “To fund social policy you need resources, and without security you cannot get resources.”

A major issue of the moment is whether he will try to overturn the constitution and seek a third term, which many, despite their approval of him, feel would be very bad for the country. He refused to comment on that, but it seems clear that he is still unwilling to negotiate any sort of accommodation with the farc.

One night I went to the Voices of the Kidnapped radio show, which is now in its 14th year. A group of disabled former policemen who had been in fights with the farc appeared, in the process of wheeling themselves from one city to another for peace. Distraught relatives took turns before the microphones, sending two-minute messages to their loved ones: for example, “If you’re alive, please keep fighting, Papi.” Herbin Hoyos, the show’s creator and host, said that at its height, between 2000 and 2002, there was often a line around the block of people waiting to go on the air. Those who had spent 15 hours on buses from the Caribbean coast were given five minutes of airtime instead of the usual two. Hoyos has vowed to keep broadcasting until the last hostage is home. “The farc is like a snake you keep hitting with stones, but as long as you don’t get the head, it won’t die,” he said. “They have their fangs, they have their poison, they move, they hide. They’re wounded, but they’re there.”

At 1:25 a.m., Ingrid Betancourt phoned from the Seychelles, where she was vacationing. She greeted fellow hostages still being held in the jungle. “I want you all at my side,” she said. “You are in my heart. I am certain that soon we will all be together.” Many have speculated that her rescue has made life harder for them.

Neither side is ready to give up. As Hoyos told me, “There is nothing more dangerous than a rich guerrilla, and no one more arrogant than the commander of a rich guerrilla force. And there is no one more sure of winning the war than a president with an army that gives him victories. Both sides are convinced they can still win. No conflict has ever been solved until one of the parties doesn’t feel he’s a loser.”

Ingrid’s Moment

The one person who is definitely not a loser as a result of the horrors of captivity is Ingrid Betancourt, who has taken many opportunities to position herself as a kind of spiritual touchstone in the world as well as a go-between in the peace process with the farc. In September she had a private audience with the Pope, after which she called a press conference in Rome to say how her faith had sustained her in the jungle. She claimed that a promise she had made to God during her captivity resulted in a sign telling her she was about to be released. In an extended interview on Caracol Radio, on the most popular morning show in Colombia, she told the audience how much Benedict XVI loves their country. “He’s very informed about what is going on in Colombia,” she told them, adding that he has the names of all the hostages and that he prays for them. She said that she had once heard the Pope mention her name on the radio when she was resting after a long march, and she recalled her shock and joy: “Because in the jungle they refer to you as cargo—we are not human but something carried back and forth. To hear a person who is a symbol of peace and to know I existed to him—he pronounced my name—I was shaking and crying.” She also revealed that the Pope had complimented her on the way she spoke to God. For a country as Catholic as Colombia, revealing that level of intimacy with the pontiff carried great weight.

In these public statements, Betancourt expressed open disagreement with the stated policy of the Colombian government not to negotiate with the farc. She called instead for giving the farc an opportunity to show a “new face”—not of “narco-trafficking or taking hostages”—to come in from the heat of the jungle and somehow enter the mainstream of Colombian politics: “I insist on the point of allowing the farc to have a space within Colombia where we can receive them with respect.” Was that a gauntlet thrown down to Uribe for the forthcoming elections in 2010? Betancourt claimed not to be interested in politics as usual, because life as a politician in the jungle was so “humiliating and difficult to face.” She said, “The word ‘politician’ was considered so pejorative in the jungle [that] we were punished differently, kept in different conditions.” Nevertheless, she said, “I would like to be there for Colombia.”

Betancourt is now the second-most popular political figure in the country, after Uribe. Her plan seems to involve becoming a kind of higher being, a secular Dalai Lama of the Andes, who will fight to free the remaining hostages. As she explained, “Everyone would understand that is my obsession.” She is probably wise to stop there, considering that a showdown with Uribe at this moment in time would be unpleasant and its outcome uncertain. But many observers agree that Ingrid will not leave the political arena for long, if she leaves at all. Enrique Santos, of El Tiempo, said, “She can be a spiritual leader for a while, but essentially she’s a pol. For three or four years she can be a saint in Europe and then come into politics in Colombia.” Herbin Hoyos told me, “Ingrid’s going to come and be a politician here. She has to. She can negotiate when she has the power. When the country gets tired of Uribe and wants someone else, it will probably be Ingrid.”

Ingrid Betancourt has expressed to me that it is still “too painful” to look back, and she keeps her specific future plans ambiguous. Ironically, if Uribe does step down, many believe he will support Juan Manuel Santos, Ingrid’s liberator, who was also her first political mentor.

No Comments