Twenty years ago I was riding down a dusty road in rural Argentina gabbing in Spanish with a local journalist when suddenly a wave of nostalgia hit me, and I realized why I felt so happy: It was just like being in the Peace Corps again. At the time, I was doing investigative reporting on Argentina’s flamboyant then-President Carlos Menem, but the discussion of local politics and poverty and figuring out how to get the information I wanted was pure Peace Corps.

When I served in the 1960s in Medellin, Colombia, as a community development volunteer, I had no thought of becoming a journalist. After my Peace Corps stint, I enrolled in graduate courses in Latin American studies. But they seemed so stifling — especially compared with living for two years amid the vibrant life of a poor barrio — that I was driven to page through the UCLA course catalogue. There I discovered “J” for journalism near “L” for Latin America, and I switched. Thus my career began.

Today, I think I echo thousands and thousands of people who can thank the Peace Corps for setting us on a path to a more interesting and fulfilling life. Back then, women could mostly be teachers or nurses or perhaps airline stewardesses if we wanted to see the world. In the Peace Corps, whatever happened after two years at our sites, we made happen, male or female; there were no limits. That was a very liberating concept for a young woman then, just as it is for anyone today.

To succeed in either journalism or the Peace Corps, you need curiosity and energy, but you also need to learn how to observe and to listen. We were constantly challenged to understand reality from a new perspective and to appreciate how others might react or behave. We learned how to empathize. We learned not to be arrogant. That is a good way to get people to open up and tell you how things work or what happened — invaluable for a reporter. Not bad for diplomats either.

Just trying to fit in at any level as one constantly has to do in the Peace Corps has served me in good stead, whether I was listening to heartbreaking tales of naive, star-struck parents allowing their little boys to spend too much time with Michael Jackson or uncovering Arianna Huffington’s fierce loyalty and reliance on her odd guru, John-Roger, to cite just two examples.

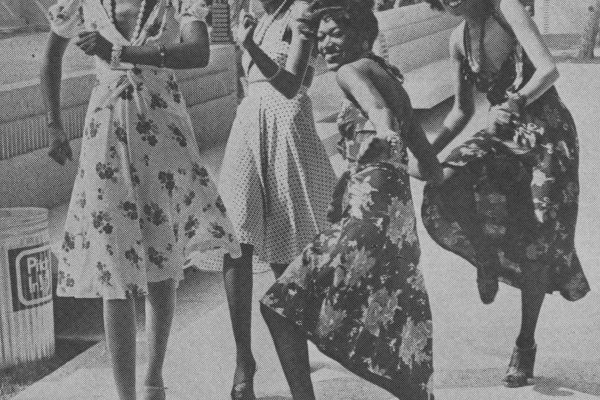

Lesson No. 1 in how not to become overly impressed with power or the trappings of celebrity comes from living in a faraway place with people who have had little formal education, only to find that the global gene pool is far more level than we comfortable Americans might have ever guessed. People of brilliance, with great senses of humor, striking musical talent or athletic ability are born everywhere. Some are able to cultivate their talent; many are not, but they often teach those of us from the so-called developed world how to appreciate the finer things, whether it’s hopping off your saddle to dance under a full moon or learning firsthand how much fun it can be to serve.

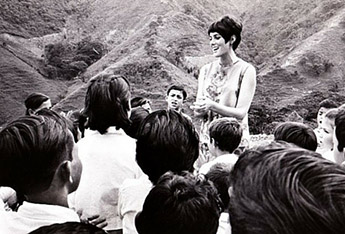

For many years I was unable to travel to the mountains above Medellin to visit the school I had helped build and that was named for me: Escuela Marina Orth. The notorious narco-traffiker, Pablo Escobar, hid out for a while right down the road from the school. When I returned in 2004, to an homage of songs, dances, a lunch and Mass in my honor, I was asked by the Medellin secretary of education to help make my school the first public one in Colombia that was also bilingual and a One Laptop per Child school. “Otherwise,” he told me, “these kids have no chance to compete in the global economy.” I readily agreed, having no idea how; it was the old Peace Corps challenge all over again. But I was also a reporter; I could find out.

Today, there are two nonprofit Marina Orth Foundations — one in the U.S. and one in Colombia — to support three Colombian schools that serve 1,200 children through public/private partnerships in both countries. Each primary school child has a computer, is taught English and learns leadership skills. My plan is to have a national network operating in Colombia within four years.

After my husband, Tim Russert, died suddenly in 2008, I was back in Colombia within six weeks to report on the army rescue of five hostages, including the politician Ingrid Betancourt, taken years earlier by FARC guerrillas. I was also able to revisit my school.

In the wake of Tim’s death, I realize the solace it gives me to be able to help these beautiful children go on to a better life. Here was the best possible legacy, taking me from darkness to light. Once again, I had the Peace Corps to thank.

Maureen Orth is an author and special correspondent for Vanity Fair. She is on the opening panel March 2 in UCLA’s commemoration of the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary.

Originally appeared in LA Times