Last January, Jennifer Wright began telling close friends that she was getting letters from an anonymous stalker and threatening phone calls. She said they warned her to stay away from the choir director at her church, a divorced man who made it no secret that he found Jennifer attractive. Jennifer, 32, was married to Master Sergeant William Wright, 36, a career army man for 18 years, assigned to the Special Forces and seemingly away on duty more than he was home. After 12 years of marriage, Jennifer had begged Bill to leave his job or at least find a way to be home more, but he refused, and their relationship had been shaky for some time. In 1991, Jennifer had left Bill for a short period, only to return and ask forgiveness. Two years ago she became attracted to another man and, according to a friend, confessed it to her husband when he returned from Bosnia. She told friends that he had stayed angry with her ever since. In February of this year he left for training in Georgia, and in March he was sent to Afghanistan.

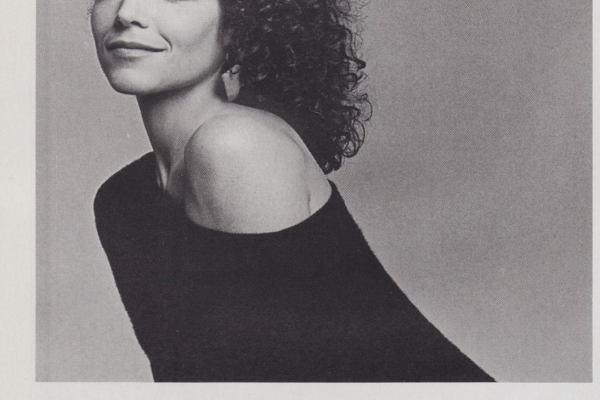

Jennifer, a pretty, slight brunette from Mason, Ohio, was only 20 when she married Bill, in 1990. In August 1998 they moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where Jennifer homeschooled their three sons, now 13, 8, and 5, and appeared to be “a perfect Christian wife and mother,” according to members of Arran Lake Baptist Church, where she directed the children’s choir. During Bill’s deployments the church became the center of her life, and the mysterious calls and letters were originally thought to have come from another church member, who was jealous of Jennifer Wright.

While Bill was in Georgia, Jennifer told friends that she and her husband were getting a divorce, at his instigation. Once the threats and letters had escalated to the point where she reported someone prowling in her backyard and the burglar alarm going off, police went to investigate. Meanwhile, Jennifer told church members that she had to go to the army’s Judge Advocate General to sign divorce papers, because her husband had circumvented North Carolina’s law requiring a one-year pre-divorce separation by going to Florida, where his father lived, to file the paperwork. In early March, Special Forces soldier Stanley Harriman, the husband of Jennifer’s close friend Sheila Harriman, was killed in Afghanistan. Jennifer, with the choir director in tow, showed up to comfort Sheila and tell her the divorce was final. The children had been told, she said.

But then Jennifer attended Harriman’s funeral with Bill, who had returned from Georgia and would leave in a few days for Afghanistan. Once he was gone, “it wasn’t but a sneeze,” says Sheila Harriman, before the choir director asked Jennifer for a date. The church’s pastor gave his permission, as long as they were chaperoned, and for the next two and a half months Jennifer and the choir director appeared together everywhere. Harriman says that Jennifer told her they never went to bed together, although they were making plans to get married. At church, according to congregation members, Jennifer would denigrate Bill and say he was being investigated for a conspiracy case.

In Afghanistan in May, Bill Wright ran into a fellow church member, who informed him that his wife was dating the choir director. Wright, who had no inkling of the romance, immediately called the pastor. “Jennifer is my wife,” he reportedly told him. “I love her.” The pastor contacted Jennifer and took her up on her offer to produce the divorce papers. Instead she presented him with another stalking letter and said the hard drive on her computer had mysteriously crashed. The pastor, according to his wife, told Jennifer she needed help beyond anything he could do for her.

Bill Wright secured permission to come home from Afghanistan and deal with his “personal problems,” and military spokesmen say he had a brief session with an army chaplain. Jennifer claimed to friends that Bill was setting her up. But when Sheila Harriman threatened to report Bill and have him arrested—by then she had learned that the police did not believe Jennifer was being stalked—her friend broke down and tearfully confessed. She said she had responded to the choir director, Harriman says, because “he was the only one to pay attention to her. She did it for the attention, because she was lonely, miserable, depressed.” Unable to break away on her own and reluctant to abandon the precepts of her church, she had fantasized that she was divorced and had entangled many members of the congregation in a web of deceit. The strain of having to stay in an unhappy marriage was so great that Jennifer had lost 20 pounds, dropped much of the homeschooling, and stopped paying the bills.

Finances had often been a problem, especially when Bill would take off. “He would leave her there with all the bill collectors calling and go on a mission,” says Jennifer’s father, Archie Watson. “It was tough for her.” Sheila Harriman says, “She just wanted somebody who was there—there all the time—who could show her attention. She was very, very lonely, a homeschooling mom for six years with three boys. All the life she had was a few friends, the church, and waiting for Bill to come home.” Jennifer’s sister, Donna Walker, says, “He put the army before my sister. He put the army before anyone.”

Once home, Bill found that all of his belongings had been put out in the shed and the garage. He moved into the barracks at Fort Bragg, but he was adamant about wanting to stay married. “He said he would do anything not to get a divorce,” says Archie Watson. A normally shy nondrinker and a stutterer, only five feet four, Bill came home every day, but, according to what Jennifer said and neighbors told her family, he began to drink and behave strangely. Jennifer told her mother he was a completely different person after he came home from Afghanistan. He would fly into rages—just as he had when he returned from Bosnia—and get mad over insignificant things. Jennifer’s parents visited in late May. “He was like a different person to me and to his boys and to her,” says Archie Watson. “He’d be talking to you and then he’d go off on something else, something unrelated to what you were talking about.” Other times he would just walk away.

Between early May and the beginning of June, Bill Wright sent three E-mails to Tracy Quinn, the family-readiness specialist at Fort Bragg, but family members say Quinn did not respond. Quinn told Jennifer’s family that she had intended to respond but had just not done so. Special Forces public-affairs officer Carol Darby, however, says that although Quinn did not meet with Wright she sent him a list of resources. The army is not releasing the contents of Bill Wright’s E-mails, but relatives and friends who have seen them say they were asking for help, albeit cryptically. In one, Archie Watson remembers, Bill wrote that “his wife’s gonna leave him—she’s asking for a divorce. He has three boys, two cats, two cars, and a house. ‘What would you do?’ ” In general, Special Forces members are loath to request help, because there is no confidentiality regarding psychological counseling in the army. Visits to a mental-health professional are noted on a soldier’s record and can easily lead to his security clearance being revoked, which can be a career breaker. “He specifically asked for any type of help he could have, anybody he could talk to,” says Donna Walker. “He asked for help, period.”

The last time she talked to her sister, Walker says, Jennifer told her, “He’s smothering me; he won’t leave me alone.”

On the night of Friday, June 28, Jennifer joined a group of women from her church at the home of Connie Veeder, a Creative Memories consultant, for a kind of Tupperware party for materials with which to make distinctive photo albums combined with “journaling.” “She was one of my best customers,” says Veeder. “All of her albums were up-to-date.” Veeder saw that Jennifer was troubled. “There was something on her mind. She kept making negative comments about her marriage.” Jennifer hung around at the end of the session to ask Veeder about becoming a Creative Memories consultant herself. “I have to get a job,” she said. “I have to earn extra money, but I have to stay at home, because I’m homeschooling.” Veeder gave her details. Jennifer did not have quite enough cash to pay for her materials, but she promised to return the next day with what she owed. She had plans to have dinner and go to a movie on Saturday night with her old friend Kim Bunts, a native of Fayetteville living an hour away, who knew she needed cheering up. Neither Bunts nor Veeder saw Jennifer the next day or heard from her. Finally Bunts went looking for her. “I was worried she might do something to herself, she was so down.”

Bill Wright, police say, entered the house about 7:30 on Saturday morning, June 29, ostensibly to pick up some tools. His wife was still in bed. They began to argue about divorce, and within minutes Bill picked up a baseball bat and struck her. Their oldest son, Ben, came to the closed door of the bedroom, but his father told him that his mother had a headache and that he should leave. According to the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Department, it is unclear where the other children were in the small house the couple had purchased only a year earlier.

Bill Wright would later explain what happened next. “Something just snapped in my mind,” Archie Watson said his son-in-law told him. Three weeks later, Wright confessed to police that after clubbing his wife with a baseball bat he had strangled her. He wrapped her body in his parachute-recovery bag and buried it in a wooded area bordering Fort Bragg, where he had sometimes gone squirrel hunting. He returned home in the afternoon and took his boys fishing. On Sunday morning, his 36th birthday, he swerved off the side of the road in Jennifer’s 2002 Mitsubishi Montero S.U.V., blew a tire, and plowed into a pine tree, totaling the car but escaping unhurt. On Monday he called the police to report his wife missing, adding that it was not the first time she had taken off.

The next three weeks were a nightmare for Jennifer’s family, who went to Fayetteville to prod police to look for their daughter. Initially, they did not want to believe that Bill had anything to do with her absence, but his behavior was baffling. When Jennifer’s friend Franziska Hawkins found Bill in the yard washing his car with the boys, she asked, “What’s going on? Your wife is missing.” “No big deal,” he replied. “If you asked him a direct question, he’d segue into something that totally didn’t make sense,” says Hawkins, who saw Wright every day. “If you asked him about her wallet, he’d talk about loading cargo planes to go to Afghanistan.” Kim Bunts says, “He was rambling like crazy, saying she was having affairs—did I know so-and-so,” all right in front of the children. Bill apparently also paid a lengthy visit to the choir director, who has since left town.

On Friday, July 19, the police asked Bill Wright to submit to a polygraph test and to bring his son Ben with him. His youngest son told Franziska Hawkins, who was driving the five-year-old to vacation Bible school, “We’re moving to Ohio. Daddy’s going to be gone a long time.” No one was home when she tried to drop the two younger boys off. Later that afternoon she got a call from Wright. “ ‘Can you take care of my boys? Somebody will bring Ben to you.’ I know now that Bill was leading [the police] out to where he actually buried her.” Kitty Griffith, a church member whose husband, Mark, reached out to Bill Wright, recalls, “The week before the murder she had brought in separation papers. That’s what he said sent him over the edge.”

At 5:07 p.m., as Lieutenant Sam Pennica of the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Department was waiting for the coroner’s vehicle to pick up Jennifer’s body in the woods where Bill Wright had led him and two military criminal investigators, he got a call on his cell phone. He turned to the investigators and said, “We got another one.”

The bodies of Delta Force sergeant first class Brandon Floyd and his wife, Andrea, the parents of three, had just been discovered. That brought to four the number of homicides and murder-suicides that had occurred at Fort Bragg over the summer. On June 11, two days after Green Beret sergeant Rigoberto Nieves had come back from Afghanistan to deal with “personal problems,” he shot his wife, Teresa, and then himself in the bedroom of their brand-new house, leaving behind a six-year-old daughter. On July 9, Sergeant Cedric Griffin, an army cook, was accused of stabbing his wife, Marilyn, more than 70 times before setting her body on fire and leaving her and her two daughters, aged six and two, to die in their trailer home. Miraculously, the little girls escaped. In addition, on July 23, police say, Joan Shannon, the wife of an army major, murdered her sleeping husband, David, for his insurance money and benefits. Her 15-year-old daughter is also being detained by authorities.

The string of deaths created a media firestorm which has not yet abated. Once again the curse of Fort Bragg had struck. It had begun sensationally in the 70s, when Green Beret captain Jeffrey MacDonald, an army doctor, reported the gruesome murder of his wife and two young daughters, murders he got away with for a decade before he was finally convicted in 1982, after his 1979 conviction had been overturned. In the 80s, Sergeant Timothy Hennis was found guilty—and later acquitted—of slashing the throats of an air-force captain’s wife and two daughters; the murders have never been solved. In 1995 another army sergeant, William Kreutzer, opened fire on a field of paratroopers beginning a dawn run, killing one and wounding 18. That same year, James Burmeister and Malcolm Wright, two soldiers who were part of a culture of white-supremacist skinheads at Fort Bragg, shot and killed two black Fayetteville townspeople. The town, where fundamentalist Bible Belt churches vie with biker bars and honky-tonks, has a rough reputation. Last January, Damian Franceschi was charged with slashing the throat of his wife, Shalamar, five days after he left the army and three days after he was released from jail for raping her and holding her mother and child hostage.

As recently as October of this year, Jonathan Meadows, a disgruntled soldier separated from his wife and the father of two, who wanted to get out of the army, has been accused of attempting to fake his own death by slashing the throat of a man he found on the Internet who looked like him. Police charge that he lured the man to his house, stuck an eight-inch knife into his throat, and planned to set the house on fire. The victim, however, did not die and managed to extract the knife. Meadows later turned himself in. His wife, Thea, has since told investigators that her husband had twice thrown her and her three-year-old daughter against a wall. However, Thea Meadows never reported this domestic violence.

“Fort Bragg is a culture unto itself,” says army chaplain John Wetherly. “They know they’re the first to go. It takes training to be aggressive. You have to be trained to be an institutional killer, so you build a culture around it.”

While the majority of families at Fort Bragg dwell happily and peacefully, there is a distinct macho imprint on the place. “There’s a saying,” says former Special Forces medic John Lown, “that to be in Special Forces you need a Harley-Davidson, a Rolex watch, a Randall knife, a sapphire ring, and a divorce.” Fayetteville—jokingly known as Fayette Nam—is halfway between Miami and New York and has a heavily transient population; the major highway, 95, is a notorious drug route. About 130,000 people live in Fayetteville proper, and another 130,000 from the surrounding area are connected to the military. There are 45,000 soldiers assigned to Fort Bragg, and 11,500 family members live there; nearly 4,700 children go to Fort Bragg’s nine schools. Some 10,000 civilians also work there.

What most Americans probably do not appreciate is the level of sacrifice required for a career in the military these days. Those in command often explain that the end of the Cold War brought substantial cutbacks to the army and more work for everybody. Some Special Forces personnel at Fort Bragg are gone between 200 and 300 days a year. Because of the situation in Iraq, certain units have already been away for a full year. Often the soldiers cannot even tell their families where they are going.

The wives are left to cope alone with the children—large families are commonplace—and both spouses face difficult re-adjustment each time the soldier re-enters the family. Their basic needs with regard to housing and health care are provided, particularly if they choose to live on the post, yet Bill Wright, for example, after 18 years in the army, with allowances for dependents, was earning about $50,000 a year. When he was away, the family sometimes got less, because the army would deduct the amount it cost to feed him.

With war looming in Iraq, and the U.S. intervening all over Africa and Latin America, there is sustained stress on military spouses today, and the army finds itself having to provide a panoply of family services. “Twenty-five years ago the old adage was ‘If the army wanted you to have a wife, they would have issued you one,’ ” says Colonel Tad Davis, the garrison commander of Fort Bragg. “Now, just as I will never leave a fallen comrade behind in battle, the same thing applies to army families. We’re not going to leave them behind.”

Davis, who functions like the mayor of a medium-size city, talks a lot about increasing “connectivity” with families. “Soldiers we see every day. The spouse is on his or her own,” he says. “Yet you don’t want spouses out there isolated.” Davis explains that when troops are overseas looking for “mines, booby traps, and snipers, we don’t want them thinking about whether their car is running back home. That is why it is important they know people back here are looking out for them.” Davis says there should be regular visits to military dependents to determine such things as: How long has it been since that diaper’s been changed? What’s in the sink? Is there food in the refrigerator? At the same time, people don’t want too much interference in their lives. Therefore, Davis says, it is imperative for commanders to know what services are available to their soldiers and their families and to direct them accordingly.

Three of the slain wives, however, never asked for help, and recent congressional meetings on domestic violence held in Fort Bragg revealed that family-readiness personnel were carrying three times the caseload recommended by the Department of Defense. “The services available for women at Fort Bragg are terrible,” says Christine Hansen of the Miles Foundation, which studies domestic violence in the military. “They are not well staffed, and the training is poor.”

“I would have no way of knowing how to get help,” the wife of a Delta Force soldier who was friendly with the murdered Andrea Floyd told me. “I wouldn’t go to a chaplain unless it was a spiritual thing. If anything else is available, I didn’t hear about it.” Others disagree. The wife of an army commander told me, “I don’t think you’ll find any other profession that provides half the services the army provides for families. But it’s up to the person to use them. We’re required to have monthly support-group meetings. I’ve planned many, and then two wives show up.” Family-readiness specialist Tracy Quinn, who has 88 units to look after, says, “The hardest part of my job is getting them in there. We can’t make them.”

The Fort Bragg killings became instant lightning rods for various constituencies. Among the most vociferous were those who find fault with the army’s policies, or lack of them, with regard to domestic violence. A number of Department of Defense studies have been mandated by Congress since 1989 to look at domestic violence in the military. According to Hansen, “They are not just re-inventing the wheel. It keeps spinning and spinning. We know from civilian society and practices and 35 years of work what the wheel should be. The military keeps spinning.” If a Fayetteville police officer is called to the scene of a domestic dispute and sees any mark whatsoever on the complaining party, he is bound by North Carolina law to arrest the partner, who can be detained for a minimum of 48 hours, and the incident is treated as a crime. Military police responding to complaints on the post have wide latitude, and many, if not most, disputes are treated administratively. One former wife of a Delta Force soldier told me that because she tried to shield herself from her husband’s blows she was judged to be “a co-aggressor” and received no protection at all.

A reliable statistic of how much domestic violence there is in the army compared with civilian life is hard to come by, since the army has no uniform measure and counts only incidents between legally married spouses. A 1998 study based on army-commissioned numbers from 1990 to 1994—adjusted for age, race, and unemployment for the purpose of comparison with civilian society—found an insignificant increase in moderate domestic violence. However, in cases of severe physical aggression, the army numbers were more than three times higher.

Another vocal group consists of those who believe that the anti-malaria drug mefloquine, also known as Lariam, which is routinely given to soldiers going to areas such as Afghanistan where malaria might strike, can cause serious psychotic effects which can lead to egregiously aggressive behavior and even suicide. The drug’s manufacturer, Hoffmann–La Roche, was recently forced to make the warning on its label read: “May cause psychiatric symptoms in a number of patients ranging from anxiety, paranoia and depression to hallucinations and psychotic behavior” as well as rare cases of suicide, “though no relationship to drug administration has been confirmed.” Although the World Health Organization claims that only one in from 6,000 to 10,000 people is adversely affected by the drug, more than 100 former Peace Corps volunteers claim that they suffered psychiatric effects from taking Lariam, and Canadian troops refer to the “Psycho Tuesdays” and “Nightmare Wednesdays” they have had after using it.

Alcohol is believed to exacerbate Lariam’s effects. The “racing-thoughts behavior” exhibited by Bill Wright, for example, who did take Lariam and who is reported to have been drinking during the period before he killed his wife, seems to some a kind of Exhibit A of the negative side effects of the drug. Wright’s erratic patterns “could be symptoms for a lot of things,” says U.P.I. reporter Dan Olmsted, who with U.P.I.’s Mark Benjamin has broken the major stories on the drug’s dangers, “but it’s a dead ringer for Lariam.” Wright’s lawyer has recently sent a neurological specialist to examine him.

A third group, which includes the local police, does not think Lariam or being in the military had much if anything to do with last summer’s murders and suicides. There has been a general upsurge in the number of domestic killings in North Carolina this year, which ranks sixth in the nation for murders of women by men. By mid-October, unofficial tallies put the number at 47—7 more than the total for all of 2001. Each of the four slain wives at Fort Bragg was suspected of infidelity, and all four had decided to get on with their lives without their husbands. At least three of the marriages had apparently been in trouble for a long time, and the deaths occurred at the most dangerous moment in terms of domestic violence—the moment of separation. To the cops these were classic, open-and-shut cases. “Ultimately what this boils down to is, is it unusual for these chains of events to have occurred in Cumberland and surrounding counties in these numbers, and the answer is no,” says Fayetteville police sergeant Alex Thompson. “Because the military is a product of their civilian environment, and we deal daily with domestics, as does the county, and we do see violence as a result.” Lieutenant Pennica of Cumberland County adds, “What does the military have to do with this? Nothing. When these murders or suicides happened, it never struck us as unusual or out of the ordinary.”

Not so, a retired female general told me. “These crimes are about disrespect for women as a group, and it’s no coincidence that it came from a group that excludes women.” She continued, “People died. What shouldn’t have happened? Was it preventable through normal processes available to the army?” She paused and added, “We maintain our vehicles better than we maintain the mental health of our soldiers.”

All of these responses are parts of the whole truth. I have learned, for example, that the Department of Defense’s task force has been working on domestic violence in the military for two years—there’s a year left to go on the study—and it still hasn’t come up with a clear definition of domestic violence. As for Lariam, one former White House official told me, “We stopped taking it on overseas trips. Secret Service guys would hallucinate on it, jump up on top of the bed in the middle of the night shouting, ‘Don’t go there!’ ”

Because Bill Wright, Brandon Floyd, and Rigoberto Nieves had all served recently in Afghanistan and were considered excellent soldiers, I will concentrate on their cases. It is noteworthy that none of their slain wives had ever previously reported being abused physically by her husband.

Roughly a half-hour outside of Fayetteville, in Stedman, North Carolina, on a country road lined with corn and tobacco fields, is the idyllic $240,000 house that Andrea and Brandon Floyd and their three young children moved into less than a year ago. It has a wraparound porch, a lawn out back the size of a football field, and a shed that could hold the horse they were planning to buy for their eight-year-old daughter, Harlee. “I’m really loving family life and we’re having happy times,” Brandon, a highly decorated anti-terrorist fighter, E-mailed his mother, Dawn Daniel, in January 2001. He spoke glowingly about the children, a daughter and two sons, now aged eight, six, and four, and characterized his wife, Andrea, an army veteran, as being “a selfless person” with “a kind heart.”

Both Brandon and Andrea were tall, athletic, good-looking, and driven. Her hurdling records still stand at the high school she attended in Alliance, Ohio; he was a triathlete who could run two miles in nine minutes plus. They raised Labrador retrievers, which meant that Andrea had puppies as well as children to care for. Brandon, who was very weight-conscious, admonished Andrea to diet, though she was not overweight. She was a great cook, however, and she wanted to make their new house—which represented a considerable step up for them—perfect. Brandon had been moving through the ranks very quickly, from ranger to Green Beret to a member of one of the vaunted and ultra-secret counterinsurgency A Teams of the Delta Force. His pay had shot up to about $48,000 per year. He had been in and out of Afghanistan three times, though late last June he told his in-laws the “real war” was in Iraq, “but they just couldn’t get in there.” Andrea, meanwhile, had taken a job managing the footwear department at a new sporting-goods outlet in Fayetteville.

A trained killer skilled in surprise attack, Brandon was a master scuba diver and parachutist who executed military sky-dives wearing full combat gear and an oxygen mask. He had won the Bronze Star for valor against an armed enemy. To his officers and buddies alike, he was “a true American hero,” a soldier’s soldier.

It was a strain to segue continually between bunker and hearth, but Brandon was determined to have both. He came from a home in which there had been a divorce, as did Andrea, and they both placed a premium on being devoted parents. The family attended a local Baptist church and Sunday school, and the couple did not curse in front of their children. “We don’t even say ‘stupid,’ ” Andrea told the woman who ran the neighborhood day-care center. Brandon, the son of a retired army colonel, had three sisters and as a child had ricocheted back and forth between parents. In his senior year of high school, in Arkansas, he fathered an out-of-wedlock child, broke with his mother, and went to live with his dad in Virginia. Determined to have his often absent father’s approval, he joined the military right after graduation. Brandon met Andrea when they were both stationed in Germany. They would go skiing and mountain climbing together. Andrea became unexpectedly pregnant, but Brandon did not marry her until their daughter was a year old.

‘Brandon was a perfectionist,” one of the soldiers in his unit told me, “always saying, ‘I gotta do better.’ ” Apparently he couldn’t keep himself from being just as tough on his wife. “Sometimes I say things I shouldn’t say,” he once confided to his friend. “He wanted a beautiful, blonde, all-American girl, and he had one, but Brandon was the type of person who never appreciated what he had,” says his sister-in-law Amanda “Mandy” Nobles. “He wanted the beautiful house, the beautiful wife, beautiful children. He wanted everything to look … like Pleasantville.” But if Brandon was a perfectionist and a combat daredevil, Andrea also put herself into extremely high-pressure situations.

In late 1999, with her husband’s approval, she took the unusual step of going onto a Christian Web site and offering herself as a surrogate mother. Childbirth had been easy for her, and she felt this was the ultimate gift for people who couldn’t have children. Andrea found a childless couple in Charlotte who paid her to carry three of their fertilized eggs. She had to inject herself with hormones and wear hormone patches to get the pregnancy going, but in November she delivered twin girls. She and Brandon became the godparents, and the other mother acted in turn as a real-estate adviser for them. That was perhaps the last happy time of their marriage.

The relationship had been having its ups and downs for years, settling into ever more negative patterns of fighting. When they were living in Fort Campbell, Kentucky, before transferring to Fort Bragg in 1999, Brandon’s “team” was known as a party team, macho and bawdy, composed mostly of single men, whom Andrea did not like having around the children. During the short periods Brandon was at home, he would nitpick about everything. “She’d get weighed down with the kids. You could tell when she really needed to go for a run—she would get up at 4:30 or 5 a.m. to run because she wouldn’t be able to during the day,” one friend told me. Brandon was gone much of the time—frequently missing major holidays—and often Andrea had no idea where he was, though her mother, Penny Flitcraft, says she never complained. “Military wives don’t complain about deployment. That’s just the way life is,” Flitcraft told me. “That’s the price as Americans they pay for their husbands to serve the country. I think military wives are very much overlooked and underrated.”

Like many such wives, Andrea had power of attorney to run things while Brandon was away. “You’re overseas, your wife has to take charge, and things are different when you get home,” Brandon’s Delta Force buddy told me. “If you put two roosters in a pen, they’re going to fight.” For Andrea, closing on the house while Brandon was deployed and taking the store job represented significant changes in the family’s lifestyle and gave her more self-esteem and independence. Perhaps she began to think that Brandon was holding her back. For more than two months at the end of last year, Andrea’s mother had the children with her in Ohio while Andrea threw herself into decorating the house—for Brandon, her mother says, though her sister, who went to help her move, found her looking older than her years, with “a sadness in her face.” During the next few months Andrea began socializing after work, and when Brandon came home in mid-January their fighting got worse. After Andrea and her sisters surprised their mother with a group photograph, Brandon’s comment when Andrea showed it to him was “Why didn’t you do your makeup like Mandy? Look how beautiful Mandy looks, and you just look frumpy.”

When Andrea called her mother in March, she had been crying. “She wasn’t a crier,” Flitcraft says. “She just said things weren’t real good, things weren’t happy.” Neither Andrea nor Brandon sought help for their problems. “No, you don’t seek counseling,” says Flitcraft. “If a woman goes to seek marital counseling, there is no confidentiality on that. That goes straight to the commanding officer. He in turn drags his soldier in and says, ‘What the heck is going on in your family?’ ” Andrea’s sister Mandy interjects, “Plus, it goes on your permanent record. It goes against advancement—it’s a sign of weakness.” Brandon’s Delta Force friend told me, “They have this thing that to get a security clearance you can’t go see a psychologist. They have this form that asks if you have seen a mental-health professional. If you say yes, in this line of work you’re done.”

That spring things got worse. Brandon was laid up with knee surgery, and his stepmother, Char Floyd, came to help care for him. He was supposed to go away again in May, and Andrea was working a lot at night. “They were never together—you never saw them together,” said their next-door neighbor Charlotte Nelson, who also said that sometimes strange cars would be parked behind the shed at night when Brandon and the kids were gone. Andrea called her mother in June and said, “Mom, I don’t think I can do this anymore. I just don’t. I’m just tired of working at it—it’s not getting any better. This isn’t good for the kids; it’s not good for any of us.”

“Andrea always said that divorce just wasn’t ever going to be an option in her life. And I think that they had this inexplicable tie,” says Flitcraft. “As unkind as the marriage was, I don’t think that either one of them really knew how to say good-bye.”

At the end of June, Flitcraft asked to have the children visit again. Andrea was going to drive them up and stay a few days. She was halfway between North Carolina and northern Ohio when she had to turn back. Brandon wanted to come, too, she said, to say good-bye, because he was leaving again soon. (It turned out to be for only two weeks’ training in Washington, D.C.) Flitcraft theorizes that Brandon did not want Andrea to talk about divorce with her family and have them reinforce her feelings. “Either that or he was afraid she wouldn’t come home at all,” says Mandy, “that she would just stay with us.” They delivered the children but stayed only two and a half hours. He had to go to Washington the next day, July 1. Police say their fights continued on the phone after that, and they believe she told him she wanted a divorce.

The night before Brandon got back, according to the police, Andrea stayed out late partying with friends. “I’ll party tonight because I have freedom,” she told them. “Tomorrow he’s coming home.” She had the next day, Thursday, July 18, off and was not home when Brandon arrived. He called her to say he was going to cut the grass, and apparently they got into a shouting match on the phone. In the front yard Brandon chatted with his neighbor about having the neighbor’s gun repaired. Brandon always carried a small handgun, a .380 semi-automatic pistol. No one heard any sound from the house that evening or saw the lights go out.

It wasn’t until late the next afternoon that the bodies were discovered, near each other in the master bedroom. Only Andrea’s side of the bed was turned down. Brandon was apparently planning to sleep in the guest room. Flitcraft believes that Andrea spelled out to Brandon that the marriage was really over. Her body was found slumped on the bed. He had shot her once, just above and behind the right ear. He then shot himself in the middle of the forehead. Men who had risked their lives with him over and over, against all odds, were stunned at the way Brandon Floyd chose to die.

“Think about it,” says Penny Flitcraft. “You have been on a sensitive mission—who knows what you’ve had to do? You pull in the driveway, the kid’s bike’s in the driveway; you walk in the front door and see the ink glob on the new couch you’re still paying for—the kid broke a marker. Your wife looks up: ‘Oh, you’re home. We’re having Hamburger Helper.’ ” Flitcraft explains that Special Forces missions emphasize teamwork in which everyone has to subsume his ego and take orders all day. When they get home, she continues, they say, “Dag-nab-it, I’m going to be somebody here. I am the head of this household.” It’s different for single men. “They get off the plane and go home to their nice clean apartments. They can go to the 10,000 stripper clubs that are down there and go get their rocks off. Go get a hot meal at Mama Carboni’s restaurant down the road. And they don’t have any obligations. But this married man is being punched right back into wherever he left the day he left; I think it’s just untenable.”

A Special Forces wife who knew Brandon and Andrea told me, “The war’s real now—it’s not being simulated. A lot of wives just think, I’ve had to wait around for you for seven months, taking care of the kids. They don’t get that he’s been maybe living in a tent in subfreezing weather, eating awful food you wouldn’t put in your mouth. All the men want to do is get home and away from the hell they’ve been in, and some men come home to a different kind of hell.”

The worst of coming home, however, may be bringing yourself down from the “activate to kill” mode, particularly if you’re in an elite Special Forces unit. In the wake of the killings, the army has made plans to test psychologically all soldiers returning from Afghanistan. There are serious concerns that a longer period of “decompression” between battlefield and home is needed. An army study published in Military Medicine in 2000 found that the probability of severe spousal aggression “was significantly greater for soldiers who had deployed in the past year compared with soldiers who had not deployed.”

“I remember being so enraged when I came back from Somalia—I’ve never been that angry in my life,” says Brandon’s Delta Force friend. “I said mean things to my wife, and I don’t even remember saying them—I imagine Brandon would have said the same things. You’re programmed—you do this about 10 years, you’re a machine. Look, we’re moral, we go to church. And then you go overseas, you flick a switch. You can’t hesitate.”

Coming down at home, he says, is “bad—it’s almost like two people trying to possess your body. When I’m serving, my one job is to win for America at all costs. The price for our loss is our life. You go to bed with those demons, wondering, Did I do the right thing? People have to realize what we do, because it hurts every night when I go to bed, wondering, What could I have done?” Real war, he says, is nothing like what we watch on TV. “People don’t realize it’s all five senses. You can see it, smell it, feel it. I’ve taken brains out of my boots. When you get hair or blood on you, there’s the feel of it, the smell of it, the taste of it. You don’t forget it.” At the same time, he says, “it is addictive—I will admit it—and it’s hard coming off. We’re A-type personalities and we love to compete. I lay in cold sweats at night. It’s so hard coming down I’m shaking.”

He told me, “Please print that [Brandon and Andrea] loved each other; he was one of the top 1 percent of all soldiers in the army. It was the abandonment—I don’t think he could take it. It must have been temporary insanity, because he was one of the few people I’d trust my life with.” Remember, he told me, “when you do a job like we do, it has an effect on your mind.”

“And what job is that?,” I asked.

“Our job is to export violence.”

The army is faced with a serious dilemma: it must train soldiers to be brutal and efficient killers overseas, but how does it get them to turn the violence off at home? The military has never fully addressed this issue. Experts on domestic violence feel that the problem is actually much more about control than about anger. “When Andrea and the children visited Penny Flitcraft for the last time, Brandon said yes, no, yes about visiting; he allowed her to stay a couple of hours and then go home. That’s the behavior of a batterer,” says Christine Hansen. “There is a declared war in that house, and the declared enemy is the wife.”

Is it possible to turn the battlefield mentality off? I obtained from the army a flyer which chaplains offer as a guide for service members and their families, outlining how everyone should take it easy and go slow when a soldier comes home. There is no way of telling how seriously such a handout is taken. Military wives also get a briefing. Kathy Krach, whose husband was deployed for a year after 9/11 as a National Guard commander in Maryland, says, “They gave us a checklist: Don’t buy new furniture, don’t change the house around, don’t give them a party when they get off the bus, don’t redecorate the house or change anything—keep things the same. Don’t have a new career or a whole new look. They represent too much realization of time passed and the realization that they are losing control.”

Nothing was the same at home when Green Beret sergeant Rigoberto Nieves, 31, returned from Afghanistan last June to deal with “personal problems.” He had left in March—his unit was training the Afghan national army—and he was not due to return until August. His wife, Teresa, 28, reportedly let him know that she could not take his extended absences any longer. She complained that he wasn’t around for birthdays, or when she was sick, or for the move to the new house. Like Bill Wright and Brandon Floyd, Nieves was an excellent soldier whose life was the army, but also like Wright and Floyd he was trying to have it both ways, and as soon as his wife shifted the balance, it would appear that he could feel his control was crumbling.

Their previous neighbors at Fort Bragg said that he and Teresa had always been very considerate of each other. “He treated his wife like a queen,” his sister Ramonita Rivera says, but “he loved the army. That came first from day one.” Nieves even graduated early from Richmond Hill High School in Queens, New York, so that he could leave for basic training on his 18th birthday. He was deeply hurt when he came home from the Gulf War feeling his first wife had betrayed him. He divorced her, and in 1992 he married Teresa, the daughter of his former master sergeant. They had a daughter, who is now seven.

Lariam was prescribed for Nieves, and those who blame Lariam for the recent murders think he may have had a bad reaction to the drug. On June 6, three days before he arrived in Fayetteville from Afghanistan, he called his mother, Lillian Nieves, in New Jersey. She was not at home, but his sister Ramonita told their mother, “He did not seem like my brother.” Ramonita says Rigoberto was always “the rock of the family, the one everyone came to for advice.” But that day, she says, “he sounded weak and beaten down.” He didn’t even tell his sister that he was coming home. Instead, he said he was worried about his mother, because he had had a premonition that she was gravely ill. (She was not.) He also fretted about Teresa’s being stressed out over moving to the new house he had bought for his family, a beige two-story dwelling with green trim at the end of a cul-de-sac in Fayetteville.

When he arrived home, he found his world turned upside down—new house, new neighborhood, Teresa’s two sisters and their children there to help her move, and, to top it all off, his beloved dog lost or temporarily missing. His mother says she was told by Teresa’s sisters that he started ringing neighbors’ doorbells searching for his dog. U.P.I. reported that one neighbor found him distinctly odd and somewhat incoherent. He didn’t give his name, but merely announced, “I’m the man of the house.”

One neighbor told me that while Teresa was moving in he had witnessed a woman kicking the garage door of the house so hard that the burglar alarm went off. She was shouting for her husband to come out, saying she knew his car was in the garage and he was in the house with Teresa Nieves.

At first Rigoberto tried to patch things up. He arrived on a Sunday, and that day and the next, according to Ramonita and Lillian Nieves, the whole family went out together to museums and stores, acting as if nothing were amiss. On Tuesday evening, while Teresa was attending a class at nursing school, Rigoberto drove over to their old neighborhood on the post. He asked his little daughter to go with him, but she wanted to stay and play with her cousins. According to his mother and sister, when he got to where he was going, he was confronted by the woman who had tried to kick in the garage door. “He came home to say he had heard a bunch of gossip from her,” says Lillian Nieves. Police confirm that Nieves spoke with the angry wife.

About 7:45 p.m., Rigoberto and Teresa retired to their bedroom to discuss the matter. According to Fayetteville police sergeant Alex Thompson, Teresa’s sisters reported that “about 8:30 or so they heard a loud noise.” At about 10 o’clock the Nieveses’ daughter became sleepy and wanted her mother to put her to bed. The relatives could not open the locked bedroom door, so they called the police.

“My understanding,” Thompson says, “is that he walked into the master bathroom, shot his wife at extremely close range with a .40-caliber revolver, a Glock semi-automatic. He [then] stepped out of the master bathroom, turned, and shot himself.” No alcohol or drugs were found in either body. (The same was true of the corpses of Jennifer Wright and Brandon and Andrea Floyd.) Once the police were satisfied that he had shot his wife and himself, they closed the case. Both Lillian and Ramonita say they were told that one of Teresa’s sisters confronted the woman who had told Rigoberto the “gossip,” and said angrily, “You have two bodies hanging over you!”

These crimes seemed to open a floodgate of self-examination by the army and intense scrutiny by Congress. What was overlooked, however, was the often insensitive way the military dealt with the crushed survivors. Following the killings and suicides in just the three cases I have reported in detail, seven children awoke to find their parents snatched from them in the most unspeakable way. Unlike the orphans of 9/11, however, they were not told repeatedly how great their parents had been and how grateful the nation was to them. On the contrary, surviving families can now exchange horror stories about the treatment that compounded their grief.

Lillian Nieves, for example, had no clue that her son had even left Afghanistan when an army casualty-assistance officer appeared on her front porch on June 12, the day after the deaths, and told her what had happened. She began to scream, she recalls, and the startled officer took off, leaving her alone and in shock. After Ramonita Rivera placed an irate phone call to the army, a second assistance officer showed up the next day to apologize. It was two more agonizing days, however, before Ramonita got a call back from Fort Bragg that put her in touch with Teresa’s sisters, who did not have her number. “From day one we’ve had so many problems,” she told me, enumerating the three casualty-assistance officers who have followed one another on the case. “I call them and hear nothing.” By October the Nieves family still had not seen Rigoberto’s will or received his belongings, and numerous long-distance phone calls made to obtain them strained the family’s limited budget. Lillian could not understand a document she received in the mail which apparently names her as a 50 percent beneficiary of her son’s life insurance. To make matters worse, she told me, “I don’t understand what it means and I can’t afford to go to a lawyer.” No one in the family has received any counseling or been told what resources are available to them.

Penny Flitcraft was awakened on Saturday morning, July 20—roughly 15 hours after Andrea’s body had been discovered—to be told by her oldest daughter that she had just heard from Brandon Floyd’s stepmother only that there had been “an accident at their house” and that Brandon and Andrea had both been shot. Within an hour, a four-person delegation from the army, including a chaplain and a psychologist, was knocking on Flitcraft’s door. One of them said, “We are sorry to inform you that your daughter is deceased, and we need to see the children.” They told her it was their duty to notify the next of kin—Andrea and Brandon’s children, who were eight, five, and four—and they insisted, Flitcraft told me, that she wake them up and tell them in the presence of these strangers that their parents were dead. She was not required to tell them immediately how they had died, but, she says, she was strongly urged to do so, and she complied.

Penny Flitcraft had to take out loans to pay for custody fees, funeral arrangements, and moving the children’s belongings. She was never informed that she could go to the local Red Cross office and receive a grant or an interest-free loan to assist her with these matters. Shortly before the tragic event had occurred, Brandon and Andrea’s five-year-old son had been diagnosed with a medical problem, but he had not been treated for it. “He has a lot of suppressed anger,” Flitcraft told me.

Flitcraft was not visited by a casualty-assistance officer until the third or fourth week of August, more than a month after the deaths, and the officer candidly admitted that he didn’t really know in any detail what he was supposed to do. However, Brandon’s out-of-wedlock son from his high-school days, with whom he had rarely been in touch, was contacted by an assistance officer immediately. Brandon’s natural mother, Dawn Daniel, traveled from Arkansas to Arlington National Cemetery, in Virginia, for his burial, but it was canceled at the last minute, and she and Brandon’s three sisters were left stranded. The Pentagon, after queries from the Fayetteville Observer, had belatedly determined that it would be unseemly for someone who had killed his wife and committed suicide to be buried among our national heroes.

The children of Jennifer and Bill Wright face other grueling issues, because their father is still alive, in jail, waiting to be tried for their mother’s murder. If the army discharges him other than honorably, and it has begun steps to do so, they will lose their dependents’ benefits after three years. Moreover, at the end of three months they had not collected any money at all. Jennifer’s parents, Archie and Wilma Watson, live in a trailer on limited resources. Their daughter Donna Walker, who has custody of Jennifer’s three children, has two children of her own. Because Jennifer’s children were homeschooled, they were with their mother literally 24 hours a day, and so they have had to adjust to regular school. Donna Walker was on a stress leave from her job as a corrections officer when she got the news of her sister’s death. Her husband is a welder. The casualty-assistance officer who visited her was trying to be helpful, but he told her he was flying blind—he had never done the job before.

Archie Watson was in tears as he told me of the struggles he had had getting his daughter’s remains and her children’s belongings from Fayetteville to Mason, Ohio. The army contributed only $550 toward Jennifer’s funeral expenses. Watson considers Jennifer a casualty of war and thinks she should be treated that way. At one point, the family says, Donna Walker was told to tell her father to “shut up” and stop talking to the media so the army could do its job. Watson, like the other survivors, was not made aware that he might be eligible for casualty-assistance grants or loans.

Jonathan Sams, a local attorney, is working pro bono for Jennifer Wright’s children. He has written to the House Armed Services Committee asking that legislation be passed so that the Wright children can have their benefits until age 18 and then have their college educations paid for. In his letter he says, “As the military demands that its soldiers rely upon it for their cares and needs, so it resultantly demands that the children of soldiers rely upon the military to care for them. Though not soldiers themselves, these children are, nonetheless, reliant upon the military.”

‘Family members are often very angry and grieving, and they have no tolerance for bureaucracy,” says Dr. Connie Best, who has served as a consultant to the Department of Defense on these issues. “There need to be mechanisms—whether it’s a phone call or a personal liaison—where a victim’s family member can call and say, ‘This is what I need,’ and the person giving assistance ought to be authorized to say, ‘This will happen.’ ”

In late September, the House Armed Services subcommittee on military personnel held a daylong series of closed-door meetings in Fayetteville to discuss domestic violence at Fort Bragg and in the military in general. In its aftermath, the House passed a bill assuring that protective orders issued against offending spouses will also be served on military installations—previously that was not obligatory. In October, the Fayetteville Observer reported on a two-day workshop at Fort Bragg on ways to strengthen programs to prevent domestic violence and to cooperate more with the surrounding community to deal with its effects.

Last May, before the deaths had occurred, the House subcommittee’s chairman, John McHugh, Republican of New York, wrote to the Department of Defense detailing his concerns about Lariam. In September he received a 22-page reply stating that the Defense Department was waiting for the results of a detailed study of Lariam that the Centers for Disease Control began in early 2001. The C.D.C.’s review process will begin in January.

As part of the Defense Department’s recently passed appropriations bill, Congress has allotted $5 million for victim advocates at military installations to provide confidential assistance to victims of domestic violence. The army itself has investigated the Fort Bragg cases and is expected to issue a high-level report prepared by “an epicon team,” which includes psychologists, psychiatrists, and epidemiologists studying the pharmaceutical effects of any prescribed drugs these soldiers took. However, no member of the victims’ or perpetrators’ families I spoke with had ever been contacted. Colonel Davis told me that, beginning this month, Fort Bragg and other army bases will install a 24-hour hot line for victimized individuals, but it will not guarantee confidentiality in cases of domestic violence.

The army, however, has already begun to demand more accountability with regard to how the survivors of such tragedies are treated. As a result of inquiries made by Vanity Fair to army chief of staff General Eric Shinseki, I received a call from Colonel Gina Farrisee, the adjutant general of the army, whose duties include overseeing the handling of casualties, missing persons, and mortuary services, to thank me for bringing these matters to the army’s attention. The army, she said, is currently rewriting instructions for personnel regarding cases of domestic violence such as those at Fort Bragg. “We owe them a lot more,” she added, “and I’m going to make sure they have clear guidance and can call us at the top while we are rewriting instructions for the future.”

No Comments