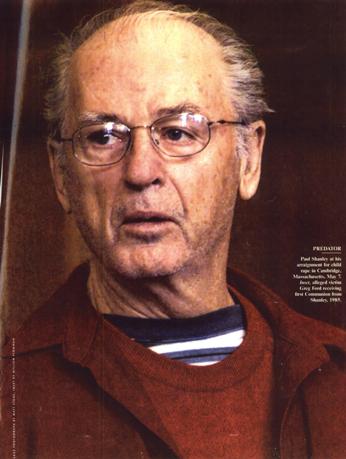

Last April, in the days before Father Paul Shanley was arrested and charged with raping a six-year-old boy in Massachusetts 19 years ago, he kept frantically telephoning a young man named Kevin English in Big Bear Lake, California. The two had known each other for 12 years, and, according to English, Shanley, 71, was desperate to keep the relationship secret in order to confine allegations of his long history of serial sexual abuse of male minors to his 30-year ministry in the Boston area. “Don’t talk to anyone,” English recalls him saying, “and don’t believe these stories you are seeing about me. They are all a bunch of lies made up by the media.” English broke his silence for Vanity Fair in late May.

Shanley and English met in 1990, after an evening Mass Shanley celebrated as a weekend-supply priest in Big Bear Lake, a Southern California ski resort. Shanley had been transferred to California from Boston as a “priest in good standing”; he was stationed in San Bernardino, an hour away. Shanley noticed the six-foot-four-inch, blond English during Mass and invited him to dinner. After learning that the 17-year-old virgin was recovering from a breakdown and confused about his sexuality, Father Shanley trotted out an old routine that had apparently worked in Massachusetts for three decades. He said he could help, English remembers, and took English back to the rectory with him. He would make it easy for the teenager to determine whether he was gay. He was willing to let English use his body for experimentation. “He did terrible things—perverted things,” says English, now 30, who has suffered several breakdowns and undergone years of therapy. “I felt so guilty—I felt evil all over.”

According to English, Father Paul wanted sex two or three times a day, and before long he was inviting Kevin down to Palm Springs, where he lived during the week in a raucous gay motel he co-owned with another errant Boston priest, Jack White, an old seminary classmate who had been treated for cocaine addiction. Dale Lagace, Shanley’s quiet, nondescript, nonclerical roommate since 1972, was usually a member of the party. English didn’t know it, but this was an old pattern with Shanley. Back in Boston in 1976, when he was sharing an apartment with Lagace at 391 Beacon Street, he would allegedly propose three-way sex with Lagace to another of his teen sex partners, confiding, “Dale likes to dress up as a woman and have sex with me.” That teenager is now one of more than a dozen victims pressing civil charges against the Archdiocese of Boston, claiming that Shanley sexually abused him beginning at age 15.

Poolside sex was English’s first experience of the world outside the small town he had grown up in. “It was Sodom and Gomorrah,” he says. Shanley and White would rent the actor Tony Curtis’s old house in Palm Springs for overflow guests, and English and Shanley would spend weekends there and at the motel. English says Shanley encouraged him to have sex with as many partners as possible and to watch porn with him. “Sex is all he talked about—it’s what drove his whole life,” recalls English, who says he resisted Shanley’s attempts to pimp him and his suggestions to “be a porn star.”

The two priests had bought property in Palm Springs in 1988, while Shanley was still the pastor at the St. Jean l’Evangeliste parish in Newton, Massachusetts, where he now stands accused of assaulting four boys, including Greg Ford and Paul Busa, who both allege that, beginning in 1983, when they were six years old, and for six years after that, Shanley would pull them out of catechism classes and anally rape them.

Shanley had pleaded ill health before being transferred to California, and in the more than 1,700 pages of documents in his Boston Archdiocese file that the court has ordered to be made public, he constantly begs his superiors for more money, in one letter alone listing 33 ailments, from “urination problems” to “recurrent scalp growths.” At one point in Palm Springs, he even got the archdiocese to pay $4,200 for a hernia operation necessitated, he wrote, by doing “too many squats.” (Shanley is still collecting a pension of more than $1,000 per month.)

Although Shanley took allergy shots, English says, he always appeared fit. He drove flashy cars, exercised regularly, and carried $500 in cash in his wallet. “He played the game to the hilt to get more money out of the church,” English says. “I don’t know where all the money came from.” According to Shanley’s sister-in-law Estelle Shanley, the priest inherited money from his mother. Certainly he and White found the funds to travel to Thailand and Costa Rica, both infamous pedophile havens. They left as their forwarding address in Costa Rica the notorious Hotel Del Rey, in San José, the capital. Bruce Harris, director of Casa Alianza, a group working to curb child prostitution and trafficking, identifies the Del Rey as “the center for world prostitution in Costa Rica.” In the bar, the Blue Marlin, which is listed on sex Web sites, Harris says, “people brag about all the nasty things done to under-age kids here.”

White’s favorite pastime in Palm Springs, according to observers, was to drive in an old limousine down to the bus station. “His passion was young black Marines,” says former Palm Springs hotel owner Jack Pray, and many would arrive from the nearby base in Twentynine Palms. Sometimes, say John Kendrick and Carter Proust, who bought a motel from White, he’d misjudge his prey and get beaten up. (White could not be reached for comment.) Shanley also reportedly cruised the station. White never made a secret of being a priest, but Shanley tended to hide it. “He called himself a ‘recovering Catholic,’ ” says English, “and said it was a big mistake ever to have become a priest.”

Paul Shanley’s sexual history with children and teens allegedly began immediately after he was assigned to his first parish, in 1960. Daniel Brennan was 14, in the eighth grade at St. Patrick School in Stoneham, Massachusetts, when he first encountered the handsome, 29-year-old, newly ordained priest. Father Paul soon learned that Brennan had no father and a mother with a heart condition, and he called the boy in. “He asked me a few questions about why I was going to Communion and all, so I told him,” says Brennan. “And then he asked me if he could check me for a hernia. So he pulled down my pants and fondled me. He told me to keep it a secret.” Brennan, petrified, immediately related the incident to his girlfriend, who would later become his wife. A month later, Brennan says, Father Shanley did it again. “I was scared, but I was stupid,” says Brennan. “I didn’t know what he was looking for. My mother never told me anything about sex.” It didn’t take long, however, for most of the boys to catch on to Father Paul’s tactics. He would pace the perimeter of the schoolyard in his cassock, former students recall, pretending to read his Breviary but eyeing the boys. He’d rub up against them, they say, and sometimes dismiss the nuns from classes so that he could pose questions about sex. Marie Brown, who had five older brothers in the school at the time, says, “They all knew to stay away from him. Some of their friends were having relations with him.”

In 1961, according to a recently filed lawsuit, Dr. Peter Devlin, whose son, Bud, attended St. Patrick, arrived home one day to find Father Shanley rummaging in their attic. Shanley said he was looking for pornographic material, because Bud, age 12, was “a sexual deviant.” The doctor told him to leave. Later that day Shanley allegedly molested Bud in the rectory, threatening the boy that, if he ever told, Shanley would destroy his father’s reputation. Bud’s subsequent downward spiral so alarmed his parents that they contacted the parish pastor, who promised something would be done, but nothing was. Mrs. Devlin wrote to Cardinal Richard Cushing, and a bishop friend of the family tried to intervene at the archdiocese. None of these complaints appears in Shanley’s file. Finally the doctor contacted the Stoneham police chief, but the family did not press charges. The chief told no one, not even his lieutenant William O’Toole, whose 12-year-old grandson, Bill, was also allegedly molested by Shanley. The only person Bill confided in was his younger brother, Michael, and he made him swear not to tell. The abuse allegedly went on for a year and a half.

Four years ago Bill O’Toole died of aids, agonizing to the very end, according to Michael O’Toole, because Father Shanley had told him that if he revealed what had gone on between them “he would burn in hell and our parents would burn in hell. Bill said Rosary after Rosary after Rosary, hoping he wouldn’t go to hell.”

It is horrifying to see up close the psychic damage allegedly inflicted by Paul Shanley. I have spoken to nine accusers, whose ages at the time they claim they were abused ranged from 6 to 21. A number have become alcoholics, some have developed suicidal tendencies and post-traumatic stress, and one has undergone electroshock treatments. Some say deeply buried images of Shanley molesting them return through recovered memory. What is truly alarming is how closely their stories resemble one another, according to their ages when they were abused. Shanley allegedly lured the youngest children with games such as strip poker, the younger teens with the pretext of examinations of their penises during puberty, the older youths with an invitation to use his body to get over their fears of homosexuality. He apparently was a master of manipulation and cunning.

Take Arthur Austin, who at 54 is highly intelligent and an eloquent writer, yet he is on disability for depression and anxiety. Repressed and inexperienced at age 20, Austin was already in an agitated state when in 1968 he sought help from Father Shanley. The priest had been abruptly transferred the year before from Stoneham to the St. Francis parish in Braintree, Massachusetts. (Shanley’s file contains a letter from a priest in Attleboro, Massachusetts, to the archdiocese reporting that in 1966 the priest had learned that Shanley had taken a boy to a cabin nearby and masturbated him. The file also contains a strong denial from Shanley.)

This is Austin’s account: He went to Shanley because a friend had told him, “He is so good with young people.” Austin had just had his first homosexual affair. “I thought, Oh, my God, I’m gay—what am I going to do?” He had stopped eating and was having anxiety attacks and crying jags. He recalls the meeting: “The first question out of man-of-God Shanley’s mouth was ‘How big is your penis? How big is your friend’s penis? … Did it taste good?’ Then he leaned over the desk and said, ‘You loved it!’ I was stunned, but I thought, There must be a reason, because he is a priest.”

Austin says Shanley declared right off the bat, “You are gay—there is no point in discussing anything else.” Austin was shaken. “I think, I’m going to hell for the rest of eternity.” But, Father Shanley explained, there was hope. “So he made the famous offer: ‘Take off your clothes—let me look at you.’ ” Austin obeyed and Shanley told him, “You can use my body, because it’s better for you to come to me for this than giving blow jobs in alleyways to strangers.” As Austin points out, “Notice the range of choice—sex with Father Paul or dirty filth in dark alleys.”

The next day Shanley took Austin to a cabin he owned in Milton, Massachusetts. The priest had frequently taken groups of boys there when he was in Stoneham—usually one more boy than there were beds so that one of the boys would have to sleep with him. “Then he raped me,” says Austin. “He told me to get on the bed and without further ado he tried anal penetration, and I completely freaked out. But he penetrated me digitally, and I had to service him orally; he wouldn’t talk to me during that time. After it was over, Shanley said, ‘You can call me Paul now. You don’t have to say Father Shanley anymore.’ That was my reward.”

For several years Austin was at Shanley’s beck and call. Shanley often took him to the third floor of his clerical residence, where they would frequently encounter Jack White, who, Austin says, could not not have known what was going on.

One night up at the unheated cabin in subzero weather, Austin dared to refuse Shanley sex. Furious, the priest got in his car and left. When he returned later, Austin was sobbing. “Come into bed now” was all Shanley said. “I ran to that bed, ripping my clothes off, and I never said no to him again about anything,” Austin recounts. “He made me do things that night that would make you gag.”

Paul Shanley was born in the working-class section of Dorchester, in St. Mark’s Parish, the second-youngest of four brothers. The family later moved to a public-housing apartment overlooking the beach in South Boston. Shanley’s sister-in-law Estelle tells me that until his arrest he had never told any of them that he was gay.

Shanley’s father, who died young, owned a pool hall and bowling alley, where Paul worked as a pinboy. According to Estelle Shanley, Paul was singled out and mentored by the pastor of St. Mark’s, Father Dunford. “The priests were revered, so if you were getting this attention, it made you special and the family special,” she says. “In those days the highest honor for a mother was to have her son be a priest.” She adds that Paul wrote beautiful letters of “encouragement, understanding, and prayer” to her late husband, his baby brother.

Shanley’s ordination in 1960 came at a dramatic historical moment. The election that year of John F. Kennedy, a Boston Irish Catholic, was tremendously empowering, and much of Shanley’s early life as a priest took place in the social and sexual revolution of the 60s. Vatican II, convened by Pope John XXIII from 1962 to 1965 to reform the church, was divided between reactionaries and progressives. One hoped-for result for many was that the vow requiring priests to be celibate would be eliminated; when it was not, 20,000 U.S. priests soon left their orders, many of them to marry, and the church has never recovered.

Shanley’s training as a priest at St. John’s Seminary in Brighton, Massachusetts, which has been called the West Point of seminaries, was strict and uncompromising. One former seminarian there says wryly, “They dressed us like girls, they treated us like boys, they called us father.” Contact with women was strictly forbidden, and the most serious offense was to be caught in someone else’s room.

Seminarians were taught no skills for coping with celibate life, and the single course given on sex had both its text and notes entirely in Latin. Cardinal Cushing, the hard-drinking, crusty, and colorful local cardinal then, once led a retreat that Notre Dame theologian Richard McBrien, who was two years behind Shanley in the seminary, has never forgotten. Cushing told them, “Men, if you’re going to do it, do it with a woman—don’t do it with another man. And if you get her pregnant, come to me—I’ll take care of it.” McBrien thinks most seminarians were basically clueless about homosexual activity. “We only noticed the gays who were more overtly feminine,” he says. “We knew them as ‘the girls.’ ” To McBrien there was no hint that Shanley’s class would produce five priests who would be accused of sexual misconduct. (The class of ’62 produced four more, and the class of ’63 an additional six.)

Shanley was strong, bright, charismatic, never afraid to challenge authority, and many of his young fellow priests cheered him on. He always focused on youth—first suburban kids, then juvenile delinquents, runaways, and hippies—and people were in awe at his ability to reach them. “He was like a hero to us radical kids,” says Patty McAndrews, 47. “He had long hair, dressed in jeans—for a priest, that was cool for a 15-year-old.”

Marie Brown says her social-activist parents in Stoneham were enthralled by the young priest, who told them he was gay and it wasn’t a sin. She recalls, “He had a big following. People felt like he was God, not an agent of God.” Sister Barbara Whelan, who met Shanley in the late 60s, credits him with inspiring her and two other young nuns to take up the vocation of ministering to alienated and abused youth and with creating Bridge over Troubled Waters, the successful resource agency for disturbed adolescents in central Boston. “He introduced us to the street,” she says. “I would say, in the 60s, Paul was it out there.”

Boston was a magnet for runaways, and Shanley quickly cast himself as hero-protector to wary street kids who did not trust authority. At a time when battle lines were being drawn throughout the country regarding civil rights, the Vietnam War, and drugs, the need for spiritual guidance among the disaffected was obvious. Father Paul boldly stepped in to fill the breach.

Shanley was not shy about promoting himself. He once invited Cardinal Cushing to have Thanksgiving with the street kids, and Cushing was so impressed that he reportedly said if he were a young priest he’d be doing the same thing. Many traditional priests, however, found Shanley distasteful and self-aggrandizing. “Essentially what Shanley did,” says lawyer Carmen Durso, who has handled several civil cases brought by Shanley accusers, “was to go out and create his own pool of victims in such a way he wouldn’t have to worry about parents’ catching on to what he was doing. He sets up this ministry with access to screwed-up kids no one cares about and access to kids who thought they were gay. When they thought there was no one else to talk to, he was there. It must have been pedophile paradise.”

Some apparently figured Father Shanley out fast. One 13-year-old runaway says he realized immediately that Shanley was offering a hot meal and a bed for the night in exchange for sex. “He forced himself on me and anally raped me, but I wasn’t going to cry. If I wanted to be fed for a few days and stay warm, that’s what I’d have to tolerate.”

Mike Ware at 14 had already run away a number of times and had just come off the street when, he says, he “read about this wonderful priest.” Shanley took him to his elderly secretary’s house for Sunday supper. While she cooked downstairs, Ware says, the evening “turned into a nightmare upstairs. I blacked it out. It didn’t get to the point of rape—I was too street-smart to let it go further.” Ware, an artist, later turned his feelings into a searing three-dimensional work. Inside a black box are a rosary crucifix and a pair of small white briefs smeared with a glue-like stain. Wooden baby blocks spell out fck you. On the back is Ware’s first-Communion picture, and the box is addressed to Paul Shanley.

Some boys Shanley allegedly raped came from stable homes. One boy saw Shanley because his mother urged him to. They had just moved to Stoneham, and the adolescent was having a hard time fitting into a ninth-grade class of strangers. Shanley met him at the rectory. “Have you ever seen the second floor of a rectory before?” he reportedly asked, and things escalated from there: “Would this arouse you? Would that?” The accuser says, “I’m a heterosexual, and I found things like kissing him on the mouth pretty disgusting.”

Week after week, according to the accuser, Shanley told the parents how “special and unique” he found their son and urged them to bring him over. Often one or two other priests were present at the rectory, and the accuser is convinced they knew what was going on. (One is now in jail for molesting children.) “Shanley would sodomize me, and when I cried out in pain he’d get a pillow to muffle my sounds. It’s a rape, and your 15-year-old body is not designed to take an object into it like that. There’s the aroma of feces—it’s disgusting. ‘Stop being so rigid,’ he’d say. He was very forceful.”

According to the accuser, Shanley would constantly invoke God’s name: “God understands the difficulties of boys your age. He wants us to open up to him, accept him into our life. Your coming before me right now is a sign of this.” Facedown on the bed, the boy would totally detach himself. “I used to fix my stare on the crucifix. I really left myself.” Since he had had no previous sexual experience, the weight of the way Shanley talked to him, he says, “psychologically broke me down. I was terrified of him, of his power. I was terrified of God. I thought he was God.” After a year, the boy stopped going to see the priest. “If I wanted to write a horror movie about how to impair someone for life, I couldn’t do better than to marry faith and sex abuse,” says Diane Nealon, who works with Roderick MacLeish Jr., a lawyer representing Shanley’s accusers. “Because you take away childhood, faith, and innocence—you take it all.”

When a major article about Shanley by Sacha Pfeiffer appeared in The Boston Globe on January 31 of this year, the accuser says, “I thought it was a sign from Heaven.” He tried to report the matter to the Boston Archdiocese, but it took a month and more than a dozen phone calls before he got an appointment. “I went in there and stated the facts. They were spellbound.… The nun taking it down kept shaking her head—‘You poor child.’ ” He remembers she said of Shanley, “ ‘He was well liked in the community.’ I had to remind her of the criminality of these acts.”

By 1970, Shanley had pretty much left the street in order to start a communal country retreat in Vermont called Rivendell for people burned out from working on the street. Some of his accusers have reported that they were abused in the farmhouse there and were invited to participate in orgies inside a big tepee.

To the outside world, with which he communicated via an in-your-face newsletter that brought the gutter home to readers, Shanley cast himself as a martyr in bulletins such as this: “ ‘Father Shanley is controversial:’ Indeed! Precisely for this did they crucify Christ.” In fact, his archdiocesan file contains nearly 200 pages of such histrionics on drugs and homosexuality, full of complaints and boasts. Of a runaway girl he found on Boston Common who didn’t want to go to a shelter, where she would be required to call her parents, he writes, “Do I leave her there to be balled by a dirty old man on the Common, or take her there to be balled by a dirty young man? I sometimes choose the latter. Imagine? Much of my life these last few years has been choosing not twixt good and evil but the lesser of two evils. My God, I’ve even taught kids how to shoot up properly!”

Since all these writings come straight out of his file, it’s clear that the archdiocese knew where Shanley was coming from. He spent most of the 70s traveling the country unsupervised, speaking out on sex education and the burgeoning gay-rights movement, and making statements about sex between men and boys that prompted people to complain to the archdiocese. Much of that time he was living in an apartment with Dale Lagace, whom Arthur Austin remembers meeting in 1972 and describes as “very small and very pretty”—obsessed with Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli. For gay activist and writer Brian McNaught, Shanley’s support at that time was crucial: “I know that the good work many people feel I do has been heavily influenced by my association with him.”

All during the 70s, as Shanley built his outspoken, radical image, his antics of baiting the Establishment, condemning parents, and going to the press frequently embarrassed the new Archbishop of Boston, Cardinal Humberto Medeiros, Cushing’s successor, a holy man but a timid administrator, whom one priest called “the advance man for Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrow.” According to Arthur Austin, Shanley used to regale him and Dale Lagace by acting out his sessions with the archbishop, undoing his Roman collar (which he rarely wore otherwise) and saying dramatically, “If I don’t have your confidence, Your Eminence, I will suspend my priestly duties.” Then he would impersonate Medeiros saying, “Oh, no, no.”

According to his file documents, in 1974 Shanley sent Medeiros a five-and-a-half-page letter in response to one in which the cardinal stated, “It pained me recently to learn of your criticism of the Bishops’ statement on ministry to homosexuals.” Shanley had ripped into one passage in particular: “While prisoners frequently submit to homosexual acts under terror, they are not entirely inculpable.” Shanley thundered, “I deal frequently with gay prisoners who have been raped by gangs of heterosexual men in prison and I am ashamed to see such a statement in print. If this makes me disloyal or disobedient, perhaps it could be excused by my emotional proximity to raped 14 year olds.”

In 1977 a woman in Rochester, New York, wrote to Cardinal Medeiros complaining that Shanley had given a talk there on homosexuality and pedophilia and had espoused the belief that the child was the seducer and was not harmed by the relationship, and that the child was traumatized only when the police intervened to question him. Her letter was answered by Auxiliary Bishop Thomas V. Daily, now Archbishop of Brooklyn, who simply said that Shanley was responsible for his own beliefs in these matters.

Shanley probably pushed the envelope furthest by attending a daylong, invitation-only conference in December 1978, described in a February 1979 article in the Boston newspaper Gaysweek as “the first ever semi-public gathering in North America of men who are involved in relationships with male youngsters.” Shanley was cited in the article for having related the damage done by one set of parents, who had turned in the lover of their young son, with the result that the man was put in jail. “And there began the psychic demise of that kid,” Shanley commented. He concluded, “We have our convictions upside down if we are truly concerned with boys—the ‘cure’ does far more damage.” Right after the conference, 32 men and two teenagers (the paper does not give names) caucused and founded the North American Man Boy Love Association (nambla). One of Shanley’s accusers told me that Shanley had shown him pictures of very young nude boys, “some with erect penises.”

Whenever Cardinal Medeiros tried to rein Shanley in, he would respond with impertinent letters containing veiled threats about going to the press. In 1979, it appears, Medeiros had finally had enough. In the Shanley file is a rough draft of a letter that may or may not have been sent, criticizing “this constant focus on yourself” and removing Shanley from his ministry, which Medeiros says has “contributed significantly” to people’s confusion “on the issue of homosexuality.” The cardinal continues:

I have changed the assignments of many priests over the years but this is the first time that a priest has gone immediately to the press and radio.

This reaction by you as well as your comments on the airwaves and your recent letter has given added clarity and insight to me concerning you and things I did not wish to believe about you.… I reject completely your accusation that I am inflicting punishment on homosexuals and their families. In fact, if I continue to leave you in this work that is the worst damage I could inflict on them in the long run. I shall pass over in amazed but laughable silence the threats you invoke against me concerning further public pronouncements—this time about our Seminary.

The cardinal ends by urging Shanley to get “out of the limelight and involved in the ordinary everyday work of a priest.”

By then, even the Vatican had become aware of Father Paul Shanley. Cardinal Franjo Seper of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome wrote to Medeiros regarding now purportedly lost tapes Shanley had made entitled “Changing Norms in Sexuality,” in which he disagreed with church doctrine that being homosexual is not sinful but that homosexual acts are. In his seven-and-a-half-page reply, Medeiros says he has transferred Shanley to “a regular parish assignment” and told him that he was not to work with homosexuals. Shanley, upon hearing this, he continues, “went to the press,” casting himself as a champion of downtrodden gays. Medeiros concludes, “It is on this subject of homosexual acts that Father Shanley presents confusing and distorted teaching. I believe that Father Shanley is a troubled priest and I have tried to be understanding and patient with him.”

Thus Shanley constructed a perfect foil: the church’s “backwardness and rigidity” regarding homosexuality. Medeiros even mentions in his letter how widespread homosexuality is in American seminaries. Would the church dare attack anyone so willing to go public and confront the hierarchy itself?

When I met John Harris, he was wielding a picket sign that read, god is truth, not lies, and protesting the Boston Archdiocese’s policy of shuffling priests such as Paul Shanley from parish to parish after allegations of sexual abuse had been lodged against them. Harris was stationed outside the lush, 60-acre site of the archdiocesan headquarters and St. John’s Seminary in Brighton, where Shanley was ordained. Harris is on permanent disability and has undergone shock treatments. When he met Shanley in 1979, he was a 21-year-old virgin, struggling with whether he was gay, and very tense. Harris says Shanley suggested a massage, pulled down Harris’s pants, and anally raped him. “I thought I had to go along with it not to disappoint him,” says Harris. “I asked him to stop and he told me he was almost done.” Confused and embarrassed, Harris says, “I went back in the closet.” Two weeks later, however, he called Shanley again, and claims Shanley took him to two gay bars and a gay porn theater where couples had furtive sex behind the screen. Harris says that, when he tried to leave, Shanley told him, “I know your type. You want the suburban house with the white picket fence.” That was the last time they saw each other. “I felt ashamed. He severed my spirituality. I decided to go to gay bars and got into booze.”

In January 1979, Shanley was sent to the quiet little parish of St. Jean l’Evangeliste (St. Jean’s) in Newton, Massachusetts. The transfer was clearly intended to silence him. “Shanley went from one extreme to the other,” says Father Gerard Barry, the retired pastor of St. Bernard’s, a parish near St. Jean’s. “He became very conservative in that he ran a parish in a traditional way.” Many St. Jean’s parishioners remain devoted to Father Paul. Anne Marie Rousseau, now a minister in the United Church of Christ, came out to Shanley as a lesbian in confession. “He told me to stand up, and hugged me and told me that God loved me.” Rousseau argued with Shanley, however, over Jack White’s openly living with a gay roommate, “a black queen who painted his toenails.” Shanley, who Rousseau says had a short temper and “that priestly-entitlement thing going on,” blithely told her that “many priests never keep their vows of celibacy,” but he did not disclose anything about himself. Dale Lagace, she says, was around frequently and was allowed to go upstairs in the rectory when no one else was. (Lagace did not respond to attempts to contact him.)

Rousseau taught both Greg Ford’s and Paul Busa’s first-Communion classes, and she does not remember Shanley’s pulling the boys out in order to molest them. Neither does Verona Mazzei, mother of Busa’s fiancée, who was head of all catechism classes. According to the local newspaper, the Newton Tab, however, others do remember Shanley taking Greg out of class to punish him.

Shanley made every effort to charm his new parish, and he succeeded mightily, with one notable exception: Jacqueline Gauvreau, the confrontational daughter of his executive housekeeper. In the early 80s, Gauvreau angrily called Shanley after hearing from a 15-year-old boy she had sent to him for counseling. The boy reported that Shanley had told him it was all right to have sex with men or women and had groped him in his car. The boy said he had jumped out, and Shanley had not even bothered to go after him. Gauvreau claims Shanley said, “So what? Prove it!”

She became the priest’s sworn enemy; Shanley considered getting a restraining order to keep her from phoning him. Gauvreau called the Boston Archdiocese about him, but never got through to anyone of consequence. She became such a nuisance that a document in the Shanley file suggests, “Leave her hanging until she hopefully gets discouraged.”

In 1984 the ecclesiastically conservative but fiercely ambitious Harvard graduate Bernard Law replaced Medeiros as Archbishop of Boston, and the following year Paul Shanley was promoted to pastor of St. Jean’s. One of Shanley’s first acts was to remove parish offices from the rectory, telling people he did not care to live and work in the same space. He also had his living quarters expensively redecorated.

One day, after singing in the choir for a televised Mass celebrated by Cardinal Law, Gauvreau approached Law to tell him that Shanley was a child-molester. She claims Law said that he would look into it, but nothing ever happened, and in a recent deposition Cardinal Law says he does not recall meeting her. There is a photograph of them together, however, and two of Gauvreau’s friends say she told them right away about the boy’s allegations. “This has been Jackie’s concern for years,” Betty Morrissey O’Brien tells me. “Nobody would listen to her.”

Gauvreau says she approached Law a second time. “What do you intend to do about Father Shanley?” she asked. She claims Law said, “That is why I have my bishops.” He told her to call Bishop Mulcahy in Lynn, Massachusetts. Mulcahy’s notes of her accusations appear in the file, but no action was taken.

Today, Law admits to having seen a 1985 letter from another woman, Wilma Higgs, complaining that she had heard Shanley, in a speech in Rochester, make references to children seducing adults. A response went out from the Reverend John B. McCormack, secretary for ministerial personnel, another 1960 seminary classmate of Shanley’s, who would become his protector. A handwritten note of his at the bottom of Higgs’s letter says, “Saw Paul—he feels she basically misunderstood him.”

In the early 80s, Shanley allegedly began molesting much younger children, though he vehemently denies the charges. Paul Busa, now 24, filed the first criminal complaint against Shanley, as well as a civil lawsuit, in which he claims that, beginning in 1983, when he was six, he was taken out of catechism classes in St. Jean’s church by Shanley and molested for six years. The Boston Globe article about Shanley that ran on January 31 triggered Busa’s memory, he says, and he is now under a psychiatrist’s care. In June, Shanley was indicted on 10 counts of child rape and 6 of indecent assault and battery involving Busa and three other boys at St. Jean’s in the 1980s.

The life of one Greg Ford, 24, was also transformed by the Globe’s exposé. For 11 years Ford and his family had endured a living hell. His father, Rodney Ford, a police officer, says it began when Greg was 13. “He came downstairs from his room and his face was bleeding, and he had pierced his ear, but I looked into his eyes and I saw my son wasn’t there. It was just a hollow, sickening look.… The next morning we took him to a psychiatrist. They deemed he wasn’t safe.”

Of all the accusers I have spoken to, Ford has suffered the most severe damage. His parents explain that one part of his brain blocked out his rape memories, but at times they would begin to surface and another part of the brain would react violently to push them back down. The day his aunt brought the Globe’s article for his parents to read, Rodney Ford says, “I knew in my gut I had the missing piece of a puzzle.… I showed Greg the article … and said, ‘Do you remember this person?’ It was a couple of pictures of Shanley. He looked at them and went, ‘No.’ ” Then Greg’s mother got the photo album with pictures of Shanley giving Greg his first Communion. “He looked at the picture, put it down on the table, got up, and instantaneously collapsed to the floor crying,” says Rodney Ford. “I literally had to pick him up, and we held each other and hugged for 20 minutes, crying.”

Greg, like Paul Busa, was allegedly raped repeatedly by Shanley for six years. “The same M.O., the same pattern—torturing the kids physically as well as mentally,” says Rodney Ford. “ ‘If you ever say anything, I’ll hurt your family, and no one will ever believe you.’ At six years old that’s a very impressionable thing on a kid’s mind, never mind physically abusing him. He just ultimately destroyed my son’s life.”

When he was no more than seven or eight years old, Greg began to mutilate himself and light fires. By the time he was in the seventh grade, teachers were telling his parents that his writings were violent and bizarre. The Fords are a close-knit, loving family, but the counselors who saw Greg said he was exhibiting classic signs of sex abuse, which naturally put the parents under suspicion. Today they even admit to having wondered about each other at times. “It was after Shanley left in the early 90s that my son had a complete breakdown,” says Rodney Ford. “He was in and out of 17 institutions and halfway houses.” He tried to commit suicide twice. “Greg tried to jump through a seven-foot window,” his father says. “He severed all the tendons in his hand.” In the second suicide attempt, says Rodney Ford, “he came at me with two knives in the backyard. He wanted the police to respond and see that he was holding a knife at me and shoot him so he wouldn’t have to go on.”

“You just didn’t want to live anymore?,” I ask Greg Ford. “For how long?”

“A long time,” he answers.

Throughout his long career, Shanley had cast himself in the role of a crusader battling tired old dogma. As a routine condition of becoming pastor of St. Jean’s, he was supposed to sign an oath to uphold the teachings of the church. This, he said, “in conscience” he could not do. With equal amounts of grandstanding over his firm resolve and self-pity for his “precarious” health, he tendered his resignation to Cardinal Law in November 1989, and in the same letter stipulated how much money he wanted on “sick leave”—$1,690 a month plus airfare.

Unbeknownst to the archdiocese, Shanley had bought the property in Palm Springs with Jack White in 1988. “If you would prefer I get a job, I will although it would seem counterproductive to the healing process,” he said in his letter. He also asked for a letter certifying him as a “priest in good standing,” which he got: “I can assure you that Father Shanley has no problem that would be of concern to your diocese,” wrote Robert Banks, vicar for administration, now Bishop of Green Bay, Wisconsin, in January 1990 to Shanley’s new diocese in San Bernardino, California. Shanley also signed an affidavit for the San Bernardino Diocese stating that his record was clean. In accepting his resignation, Cardinal Law thanked him for the 30 years “you have been in the service of God … an impressive record.… The lives and hearts of many people have been touched by your sharing of the Lord’s Spirit. You are truly appreciated.”

Shanley must have felt relieved, even though “sick leave” was sometimes a euphemism for sexual deviance. Despite persistent rumors—several members of the late Bill O’Toole’s family say they phoned and wrote the archdiocese in 1988 accusing Shanley of being a child-molester—Paul Shanley was starting over, thinking happily, California, here I come.

But Father Shanley did not go to California quietly. Roderick MacLeish Jr. and Robert Sherman, lawyers for his alleged victims who have also dealt with a number of other priests accused of pedophilia, say that Shanley stands out because of his ability to manipulate. “He’s a con man with a collar,” says Sherman. “I think in many respects that you come away with the impression that the church just didn’t know how to handle him at all, that he controlled them as opposed to they controlled him.”

Shanley’s file paints a picture of a demanding drama queen, a querulous operator. During his first year in Palm Springs, he told his genial superior in the Boston hierarchy, his old seminary chum Father McCormack, now Bishop of Manchester, New Hampshire, and until recently the chair of the U.S. Bishops’ Committee on Sexual Abuse, that he needed more money in order to have his allergies treated. When the archdiocese balked at paying for allergy testing, he wrote back, “My apprehension has … exacerbated my condition and I find myself too ill to work.” In May 1990, when he was owed a check by the archdiocese, he issued an overt threat: “The media have found me and again pressure me for a story.… I would have to explain to any parishioners what has happened and that would precipitate the media whirlwind. I think the best for all concerned is medical retirement.”

When Shanley’s sick leave was up at the end of 1990, McCormack wrote to Cardinal Law’s assistant, “If he came back, I do not know what we would do with him.” Shanley got 12 more months of sick leave.

In 1991, McCormack visited Shanley in Palm Springs. Shanley lived mostly at the Cabana Club, the gay motel he co-owned with Jack White. “What do you think of my … staying overnight at your rectory?,” McCormack asked. According to Father Lawrence Grajek, pastor of St. Anne’s in San Bernardino at the time, Shanley performed only Saturday-evening and early Sunday-morning Masses every other week; he almost never slept at the rectory, and McCormack did not stay there, but he clearly visited Palm Springs. In March 1991, Shanley wrote him, “Thank you for your kindness during your brief visit to the wild west.” McCormack went to bat for him again with Law and got him more money. While Shanley shilled for additional housing money, he was renting a beachfront house with Dale Lagace in a tony part of San Diego.

For the next year, Shanley continued to complain about his health and his heavy workload of “baptisms, youth retreats, [and] penance services.” Father Grajek says, “That is an outright lie—he was only a weekender.” It was during this period that Shanley was allegedly involved with Kevin English.

In order to help Shanley acquire permanent disability status, McCormack asked him to provide a letter from his doctor. Shanley’s response, including a diagnosis of “chronic anxiety neurosis,” was questionable enough to be vetted by Dr. Edwin H. Cassem of Harvard Medical School, who has treated a number of clerical sexual molesters. Pointing out that “anxiety neurosis” is not a credible pathological definition, the doctor told McCormack that it was “not unkind to ask outright whether his avoidance of work is voluntary. Palm Springs is not ordinarily associated with a life of hardship.” Cassem wondered whether Shanley ought to be examined, but McCormack wrote that Paul would be “terribly threatened by this and uncooperative with the effort.”

In 1992, in Boston, Roderick MacLeish Jr. began to pierce the wall of priestly secrecy by representing many of the more than 100 people who had come forward in the neighboring diocese of Fall River to accuse a former priest there, Father James Porter, of molesting children. MacLeish’s stance was aggressive. “I think being raped by a priest in a Catholic culture is in many respects as serious as a homicide case,” he tells me. Porter was neither treated nor punished, merely transferred around by the diocese. The widely publicized Porter case, however, spelled trouble for Paul Shanley.

By September 1993, one of the first accusations by a lawyer—representing a 15-year-old runaway—had appeared in Shanley’s file, followed by three others. In one instance, according to an accuser, Shanley blamed his allergies. He had taken a group of altar boys to his cabin, and one had to share a bed with him. He told the boy, however, he had taken an allergy pill and was not responsible for his behavior. In the morning he took the boy to confession.

Shanley was ordered back to Boston to be examined, and he later admitted to doctors that he had had “sexual activity with 4 adolescent males,” as well as about five heterosexual relationships. He allegedly told some people, including Kevin English, that he was bisexual “but that boys were easier to handle.” When confronted, Shanley told his examiners he was ashamed. He said he wished “he had found the gay community earlier.” The archdiocese paid his lawyer’s retainer of $2,500. In October 1993, after the mother of a man Shanley had allegedly molested showed up to report the abuse to the archdiocese in order to fulfill a promise to her dying son, McCormack finally called the San Bernardino Diocese. According to Father Howard Lincoln, the diocesan spokesman there, he followed up with a letter saying that “the Archdiocese had received within the past months several allegations pertaining to sexual misconduct with a minor.” San Bernardino dismissed Paul Shanley immediately.

The Boston files, however, show that in each instance of reported abuse the archdiocese negotiated with the alleged victim’s lawyer or merely listened politely and hoped the accuser would go away. “The emphasis was always on protecting the priest and never on protecting the child,” MacLeish says. “And that’s what’s so striking. There’s nothing in these documents about the victims. So we have to ask why.”

As a result of the public outcry over the Porter case, Cardinal Law created the Archdiocesan Advisory Board to deal with sex-abuse accusations directed against the clergy, and Paul Shanley became Case 33. The board’s assessment of him was disingenuous, indicating that his accusers had said he engaged basically in masturbation, although one report had alleged oral and attempted anal rape. The board concluded, “He is an honest, straightforward person who identifies with various causes.”

By February 1994, McCormack had still not told the Bishop of Palm Springs about Shanley, who had returned to work there at the gay motel. Shanley’s medical report from the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut, where he had been examined, said he was histrionic and narcissistic and had a personality disorder. Shanley offered to move to Costa Rica or Mexico, suggesting “it might allay the concerns of the victims.” At one point he boldly proposed setting up a “safe house” for “warehoused priests.” McCormack wrote that he had had the same idea. About that time McCormack also wrote, “It is wonderful how you maintain your sense of humor in the midst of your difficulties, Paul.”

At the end of August 1994, McCormack filed the results of Dr. Cassem’s further assessment: “Father Shanley is so personally damaged that his pathology is beyond repair. It cannot be reversed.” Yet in October the advisory board weighed in once again to say that Shanley had shown no “evidence of a diagnosable sex disorder,” but that he was resistant to admitting his past behavior and was afflicted with psychosomatic illnesses. Its recommendation was to keep him out of sight—give him sick leave, have him live out of state, and prevent him from doing any ministry. Not until December 1994—shortly after Shanley returned from a trip to Costa Rica with Jack White—was he informed that he could no longer function as a priest.

During the 80s, Shanley had paid visits to McLean psychiatric hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, where he became friendly with a patient named Francis J. Pilecki. Pilecki would be forced to resign as president of Westfield State College in New Jersey over alleged sexual misconduct. He later pleaded guilty to abusing a 13-year-old boy. In February 1995, Pilecki was seriously ill with cancer, and he summoned Shanley to New York to help him run Leo House, a nonprofit Catholic hotel near Greenwich Village. Dale Lagace also came to work part-time there. At first the New York Diocese was told nothing about Shanley’s abuse history, nor were the people at Leo House.

In March there was another abuse allegation, from a lawyer representing a man who said Shanley had masturbated him when he was 13 and called another man over to watch. By then the Reverend Brian Flatley had replaced McCormack, and he contacted the New York Archdiocese to make sure no misconduct was occurring at Leo House. In the meantime, one of Shanley’s accusers was threatening to tell his story to The New York Times. An internal memo in the Shanley file states, “It would be hard to defend if any public disclosure was made about it, i.e., NYC, possibly questionable supervision, transient guests, young people, not of our making, etc.”

Pilecki soon announced his intention to resign, and Shanley expressed a desire to replace him. New York’s Cardinal John J. O’Connor would have to approve the appointment—with “strong support from Boston,” wrote Flatley in a memo. “The bottom line is, what do we do with him if he has to leave there?”

In November, recuperating from hernia surgery, Shanley received a sympathy letter from Cardinal Law: “This has been a tumultuous year for you, Paul. It must be very discouraging to have someone following you and making inconsistent demands.” In December, while the archdiocese was trying to negotiate a settlement with one accuser—another claim had already been settled—Sister Anne Karlin, a nun working at Leo House, received another call saying that Shanley was a child-molester. She wrote to Law, “Here I am with this time-bomb. Would you be so kind as to clarify Fr. Paul’s integrity and reputation and character.”

Sister Anne was told that a past problem had been resolved and that Leo House was a “good placement” for Shanley. By the end of the year, Pilecki had decided not to resign immediately, and Shanley was allowed to stay on. He promptly began campaigning to become a “Senior Priest” at age 65 and secure a pension from the Boston Archdiocese, which Cardinal Law approved. “For thirty years in assigned ministry you brought God’s Word and His Love to His people and I know that that continues to be your goal despite some difficult limitations,” Law wrote to Shanley. “This is an impressive record and all of us are truly grateful for your priestly care.”

As for Shanley’s becoming director of Leo House, before Cardinal Law could mail a letter to Cardinal O’Connor saying that he had no objection, O’Connor had rejected his appointment. Shanley decided to move back to San Diego.

“I have spent considerable time reviewing your file,” wrote Monsignor William Murphy, who had replaced Flatley. “The restrictions against living with a roommate and not living near children or known homosexuals were prudent while you were under such close scrutiny by [the accuser] but I feel comfortable in lifting those now.” Shanley was also told he could be a priest again if it was “outside of a parish or a setting which regularly involves children.”

Murphy urged Shanley to speak to Monsignor Dan Dillabough, who was in charge of personnel for the San Diego Diocese. Murphy recommended Shanley as being well suited “for administrative work, especially in the area of sexual misconduct.” Dillabough tells me he does not recall meeting Shanley, adding, “My thought and hope is we didn’t have anything to do with him.”

At least six settlements made with Shanley’s accusers through 2000 were kept confidential and have since been referred to as hush money. Roderick MacLeish Jr., however, defends them. “We just didn’t take the money and run. If you look at our settlement agreement on Shanley, it says he had to get out of active ministry, not be around children, and be in psychotherapy.”

After Greg Ford and Arthur Austin came forward to name Shanley as their tormentor in a moving, dramatic press conference, Shanley E-mailed scores of friends telling them that the stories were all lies. Then he disappeared for a few weeks, until TV channel WBZ in Boston, working with KFMB in San Diego, caught him sneaking out of the San Diego apartment he shared with Lagace.

By then the Boston district attorney was ready to arrest him. The D.A.’s office asked WBZ to hold its story overnight and allow officials to apprehend him on May 2. Neighbors in Shanley’s stuccoed building professed surprise at his arrest. He had seemed so pleasant and accommodating, though one neighbor says she had always thought he was too friendly for a reason.

Since Shanley’s arrest, the number of his accusers at St. Jean’s alone has risen to six, four of whom were pre-pubescent.

Paul Shanley may be an egregious example, but 250 priests have resigned or been suspended on charges of sexual misconduct in the United States since January. Some of these have more than 100 accusers, so the ripple effect in the Catholic Church is vast enough to be called epidemic. Like many molesters, Paul Shanley told doctors, he had been sexually molested himself, first as a teenager and later “as a seminarian by a priest, a faculty member, a pastor and ironically by the predecessor of one of the two Cardinals who now debate my fate.”

Informed individuals in Boston clerical circles believe that a deceased high-ranking member of the administration of St. John’s Seminary was Shanley’s abuser, and that the archdiocese’s fear that Shanley would go public with the information was what allowed him to operate with impunity for 40 years. People close to the case say they would not be surprised if he uses what he knows to plea-bargain.

Shanley’s reputation as a predator in Boston was so notorious that even gay seminarians were careful to avoid him. “He was known to be abusive, known to have rent boys,” a Boston-trained Jesuit in his early 40s tells me. Yet a total of four cardinals and three bishops failed to make the slightest effort to bring him to the attention of civil authorities.

There is no correlation between homosexuality and pedophilia—most pedophiles in the population at large are heterosexual—but authorities say that the victims of Catholic priests are overwhelmingly teenage boys. Abusers of teenagers, as opposed to children, are known as ephebophiles. Father Donald Cozzens, the former Vicar of Priests in Cleveland, writes in The Changing Face of the Priesthood: “Our respective diocesan experience revealed that roughly 90 percent of priest abusers target teenage boys as their victims. Relatively little attention has been paid to this phenomenon by Church authorities—perhaps it is feared that it will call attention to the disproportionate number of gay priests.”

In fact, the issue of homosexuals in the priesthood has become a lightning rod used by both sides in the current controversy. Vatican spokesman Joaquin Navarro Vals declared that gays should not be ordained, whereas the gay Jesuit I spoke with says the vast majority of gay priests are “observant” of celibacy and consider their homosexuality “a gift” which allows them to be more sensitive to prejudice. He agrees with Cozzens that what is not addressed is the “enormously high rate. There are a very large percentage of priests who are gay. I think it is acknowledged in the clergy being 70 or 80 percent.… Priests feel open to reveal themselves to other priests, but also feel for personal reasons they can’t reveal it publicly—the culture wouldn’t be ready for it,” certainly not “the clerical administrative culture.”

‘Secrecy and shame” are first cousins, a former priest and psychologist tells me. “People stay as sick as their secrets are, and institutions stay as sick as their secrets are.”

The consequences of decades of secrecy have been grave. When was the last time a cardinal was deposed? The most senior U.S. prelate, Cardinal Bernard Law, once spoken of as the first American candidate to be Pope, is now an object of scorn in Boston; his lax oversight at home while he campaigned in Rome to increase his influence will cause many charities to suffer and probably much valuable church property to be sold as the number of victims in the Boston area seeking restitution climbs toward 500. Reportedly a grand jury there is considering whether criminal charges could be brought against Cardinal Law and other church officials for knowingly placing predatory priests where they could molest minors. The Boston Herald’s Robin Washington has revealed that, even as a young vicar in Mississippi, Law protected his closest seminary friend, who had been accused of abuse. They are currently both the subject of a lawsuit there.

Many of the bishops at the recent Conference of U.S. Bishops in Dallas held Law personally responsible for their troubling assembly. At the same time, the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People produced by the conference promises that priests such as Paul Shanley will no longer be able to function. “In the past secrecy has created an atmosphere that has inhibited the healing process and, in some cases, enabled sexually abusive behavior to be repeated. As Bishops, we acknowledge our mistakes and our role in that suffering, and we apologize and take responsibility for too often failing victims and our people in the past.” The charter also quotes Christ in the Gospel of Matthew, saying about anyone who would lead the little children astray that it would be better for such a person “to have a great millstone hung around his neck and be drowned in the depths of the sea.”

No Comments