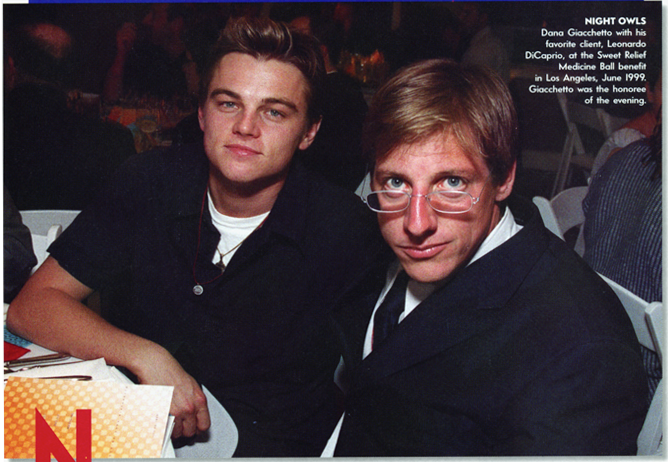

Not long ago, to be young, gifted, and financially secure in Hollywood meant that Dana Giacchetto was managing your money. While a few skeptics never could grasp how the foppish, 37-year-old money manager had gained the trust of such A-list stars as Leonardo DiCaprio, Cameron Diaz, Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, and Tobey Maguire, Giacchetto himself rarely displayed any self-doubt. Exuberant, generous, part court jester, part shrewd operator, he often partied in the hottest nightspots till five a.m., and even dined out with a cockatoo perched on his shoulder. He bragged that his company, the Cassandra Group, Inc., controlled $400 million or $500 million or even $1 billion belonging to hundreds of top-drawer clients on both coasts—major artists in SoHo (David Salle, Ross Bleckner), rock stars such as R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, and a constellation of leading figures in the film industry, ranging from actress Courteney Cox Arquette to Michael Ovitz, head of Artists Management Group (AMG). To add to his cachet, Giacchetto had formed a separate, $100 million venture-capital partnership with Chase Manhattan Bank, a Wall Street credential guaranteed to impress his glittering investors.

But the glitter is quickly being ground to dust. Giacchetto is the subject of inquiries by the Securities and Exchange Commission as well as investigations by U.S. attorneys in New York and Los Angeles, and the F.B.I. has been contacting potential witnesses. Authorities are attempting to ascertain whether or not Cassandra was involved in an elaborate Ponzi scheme, taking the money new clients gave Giacchetto to invest and putting it into deals gone bad in order to bail out older investors. In addition, the investigators want to know if Giacchetto lied to his clients about the amount of money in their accounts. Both charges are considered fraud. Giacchetto and his lawyer deny having any knowledge of such an investigation and say they have not been approached by any U.S. attorney.

Until late last fall, when the news broke that some 17 of Giacchetto’s highest-profile clients had deserted him, he was riding at the peak of his trajectory. He was throwing wild bashes with DiCaprio and the rapper Q-Tip. As a member of “Leo’s posse,” he was even named in a lawsuit brought by paparazzo photographer R. J. Capak, who claimed that, in September 1998, he had been attacked by Q-Tip when they were all outside Veruka, a New York restaurant. Giacchetto’s talent for teaming up the well-connected, and showing the Chase bankers he worked with a world they never could have entered without him, kept him away from the office far more than the average money manager. If new clients happened to call, they might be told that Dana was in Paris with Cameron, on the Mediterranean aboard Ovitz’s yacht, or visiting Leo on the set of The Beach in Thailand.

Giacchetto specialized in the sons and daughters of the rich and powerful. Mario Cuomo’s son Christopher, 29, was on the payroll of Cassandra; art dealer Arne Glimcher’s son Marc was one of Giacchetto’s best friends; literary agent Mort Janklow’s daughter, Angela Janklow Harrington, and financier Ivan Boesky’s daughter, Marianne, invested money with him; and he elevated Bob Dylan’s son Jesse, 33, to be the chairman of a publicly traded entertainment company. Many of Giacchetto’s clients were thrilled with the amount of money he made for them, and they raved about him as a financial genius.

Basking in the heat emanating from DiCaprio’s Titanic celebrity—DiCaprio lived in his SoHo loft for months at a time in 1998 and 1999—Giacchetto once proposed a deal to offer shares in the star’s future earnings, an enterprise called Leo Inc. Becoming more and more swept away in reflected glory, he also began to grant press interviews, and they marked the start of his unraveling. In the spring of 1999, in the presence of a reporter from The New York Times Magazine, he called out, “Get me Leo!” and “Get me Michael!” At the time, there was no one else in the room.

Hollywood was not amused. “‘Get me Leo’ was the death knell,” says Angela Janklow Harrington. “Believe me, it doesn’t take a lot to disengage the folks out here.” At first, “he seemed harmless,” says Bryan Lourd, a managing partner of Creative Artists Agency (CAA), who is not a Giacchetto admirer. (Lourd’s brother, Blaine, who is also a money manager, has recently acquired some of Giacchetto’s former clients.) “He was charming in his geekiness,” adds Lourd. But soon Giacchetto began popping up in the gossip columns; he even got grouped with Jeff Bezos of Amazon.com and Michael Dell of Dell Computer Corporation in an article called “The New Mini Maxi Moguls” in Interview magazine. “What he turned into was a nightclub-crawling, Prada-suit-wearing boy,” Lourd explains. “It’s all the better if you can hang out with your money manager, but he shouldn’t be getting more women than you or living in nicer places than you. They’re supposed to be sitting behind a desk.”

Last December, the Los Angeles Times and Daily Variety reported that Giacchetto’s partnership with Chase had ended abruptly and that big-name clients, including DiCaprio, Diaz, Affleck, and Damon, had taken their money out of Cassandra. Rumors of an impending scandal swirled, but nobody seemed to know what it might entail. “I have not heard one person come out publicly to say what he has done wrong,” says Michael Ovitz. Ovitz says he supports Giacchetto, “unless he has done something illegal.” Nevertheless, last summer he removed the $300,000 he had with Giacchetto for trading options, not because there was anything amiss—Giacchetto had done well for him—but because Ovitz’s accountant couldn’t decipher his statements. Bookkeeping for option trading can be a nightmare, and Ovitz felt that Giacchetto had to get his accounting squared away.

Also in December, The New York Observer caught Giacchetto in several flagrant lies: he had not dropped out “two credits shy” of a Harvard M.B.A., as he had claimed—in fact he had taken only extension courses at Harvard—and, as it happened, he had failed a trader’s exam administered by the National Association of Securities Dealers. He did not have $400 million to manage, as he had often stated in the press—it was only $100 million. According to veteran CAA agent Bob Bookman, “This is a business where people make a lot of money not because of business skills but because of creative skills. There’s a long history of people who made a lot of money in Hollywood and entrusted it to the wrong people. It’s part of an ongoing saga.”

On December 13, 1999, Giacchetto struck back. He sued his former Chase partners—Jeffrey A. Sachs, Samuel Holdsworth, and Robert L. Egan—for $300 million. He charged that Sachs had damaged his name and reputation by spreading “untrue statements and grossly exaggerated slander, rumor, and innuendo.” He charged that the other two partners, based on what they had heard from Sachs, joined with Sachs to force him out of Cassandra-Chase Entertainment Partners (referred to hereafter as the Fund). He further alleged that Sachs had contacted numerous people Giacchetto did business with to warn them that Giacchetto would become a target of investigation by authorities and was “going to get arrested.” He claimed that Sachs had also called Steve Warren, one of DiCaprio’s lawyers, which resulted in the star’s pulling out of a major merchandising deal to market DiCaprio overseas. (Giacchetto was to receive $100,000 a month in compensation.)

Sachs admits to talking to clients who called him and advising them to have their accountants scrutinize their monthly statements, but he claims, “There were no untruths. There were definitely not any defamations. And if as part of this litigation Dana wants to have his business practices fully examined, so be it.”

Sachs and Holdsworth hired former New York governor Mario Cuomo—for whom Sachs had once worked—to defend them, and in mid-February they responded to the lawsuit. They denied all of Giacchetto’s charges and asked that the suit be dismissed. They also sued for $950,000 which they had lent to Giacchetto.

The sizzling back story is that two insiders who remain close to the situation have alleged that Sachs, relying on information that he had paid a young Cassandra employee to obtain for him, called certain key Cassandra clients to warn them to get out. “No one has ever been paid by me for information,” says Sachs. “That is a pure fabrication.” Giacchetto, however, admits that he was warned about the alleged payments over a year ago, but says that “I didn’t want to believe it.”

Moreover, Giacchetto says that he had a number of calls from clients about Sachs. “They said, ‘This guy is not working on your team. He is basically abandoning you. You had better be careful.’”

Dana Giacchetto was putting up a brave front when I spoke to him in his spacious loft on lower Broadway in early February, a week before his former senior vice president, Soledad Bastiancich, was called in to the office of the U.S. attorney in New York to answer questions concerning Cassandra’s bookkeeping practices, the way money moved around in clients’ accounts, and whether Giacchetto provided clients with an accurate accounting of their funds. Giacchetto was dressed nattily in black. His cockatoo was on a perch nearby. Peter Brown, his impeccable British P.R. representative, was at the ready, and an attractive young blonde woman was making tea for us.

“After all this crap in the press, all my clients will come back,” Giacchetto tells me confidently. “I’ll continue to build value for people, and the people will realize that.” He is quite charming, short and energetic, with a shock of straight blond hair falling over his forehead. He wears wire-rimmed glasses and gestures flamboyantly. His skin is so pale that it is easy to see when he becomes emotional or nervous, because his face flushes bright red. From time to time the façade collapses, and he nearly cries when he mentions all the recent betrayals and losses. “I’m an optimist. I love people. I’ve always felt since I was a little kid I was here to do good things. I have to be more careful. I didn’t realize so many people would be working against me to create damage, and premeditating problems because of this web that I spun—this big power base—and it upset a lot of worlds. But it’s going to come back, because I’m really good at what I do.”

Giacchetto, a onetime rock keyboard player who grew up middle-class in Medford, Massachusetts, staked his business on creating “value” (money) for artists. He is remembered fondly by his first boss, Ellyn McColgan, who now heads a division of Fidelity Investments outside Boston. Giacchetto was part of a small team hired to install and support a computerized account system for the Boston Safe Deposit & Trust Company. “He was 24. A delight. So much fun, very smart, and he worked so hard. Dana was already managing his own portfolio—he owned Disney, even back then.” She adds, “He was on the fashion edge. He dressed in black long before Boston understood that as a color.”

Giacchetto started the Cassandra Group in 1987, and it became his mantra that the firm would deal in conservative, blue-chip stocks and corporate bonds. He emphasized low-risk securities and usually shunned popular technology stocks. “I always felt artists—visual, musical, creative minds—were not comfortable talking about money or hard economics, or were kept in the dark. My dream was to create an entity in which [creative] people would feel comfortable that they were dealing with people who could understand both the left brain and right brain. You could talk about capital markets and demystifying finance for people who were generally not given much data.” Giacchetto also fought for artists to own pieces of “equity” in companies they were attached to. He once even tried—unsuccessfully—to get Madonna to give up a piece of her record label when she signed Alanis Morissette, a close friend of his. “People who create content have to understand the value of their content. You’ve seen the power that emerges around these artists.”

Giacchetto’s most successful deal was to sell a 49 percent share in the small, independent Seattle-based Sub Pop Records—the original label of Nirvana—to the Warner Music Group for an astounding $20 million in 1994. “When we sold Sub Pop to Time Warner,” he says, “a lot of it had to do with the success of Kurt Cobain [who was already dead]. These deals are driven by content providers, and a lot of these people want to know, How do we access capital markets? That’s the puzzle I’m trying to get at.”

Others would disagree. “Dana’s love is to be in a room with Leonardo,” says a close associate. “He loves the feeling he can walk up to the door and walk right in. He loves that feeling much more than money.” Friends say that Giacchetto’s ultimate dream is to be sought after by everyone: Get me Dana!

‘You just made $10,000 in Nike options,” Giacchetto would coo on the phone. “Do you want to keep going?” His financial seduction was silky, and many people made a lot of money with him. “When Alan Greenspan described the market as having ‘irrational exuberance,’” says Ross Bleckner, “I thought of Dana. That’s how I would describe him.”

Giacchetto would show up on studio lots, asking young executives he had just met to provide him with introductions. Always emphasizing that he specialized in blue chips, he was also conscientious about such things as the rain forests, and he steered clear of tobacco stocks. Film producer Bill Robinson, Diane Keaton’s business partner, remembers meeting Giacchetto at the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood about three years ago. According to Robinson, Giacchetto boasted that he was part owner of the venerable star hangout. Giacchetto says he was referring to the Standard, the other L.A. hotel owned by his client André Balazs. In fact, through Giacchetto, Balazs got DiCaprio, Diaz, and Benicio Del Toro to put money in the Standard.

Several of the big star names, it should be noted, invested relatively small amounts with Giacchetto, as if they were reserving membership in an exclusive private club or the coolest high-school clique. Robinson continues: “Dana and his friends were holding forth about how he represents Leo, Cameron, Matt Damon, Ovitz—how Mike Ovitz called him every week for financial advice. He had this boyish charm, like a laid-back Silicon Valley boy-wonder star, and ‘Oh yeah,’ he said, he once happened to be in a punk band in Boston. ‘And, oh, by the way, I’m a financial genius.’ He told me he controlled $1 billion in assets and I could have an incredible return on investments.”

Robinson recalls that Giacchetto whipped out his laptop and punched up several portfolios in which Robinson could invest. Ordinarily, he told Robinson, he didn’t take anyone with less than a million. “He created this sense that you would be in this elite club and you were missing the boat if you didn’t buy in.… Plus he’d say, ‘Here are the keys to my loft, and, oh, Leo might be staying there’—always ‘I’m a winner associating with these big people.’ In a way, he exploited the incredibly sheeplike nature of all of us out here.”

To those who were market-challenged, Giacchetto would patiently explain that once they had signed his management agreement he would have absolute discretion to make trades using the money in their accounts and would receive a fee of 1.5 percent of their total assets. Unlike most money managers, however, he included moneys borrowed on the margin to buy stocks as part of that total—hardly a conservative procedure—and he chose not to disclose his performance to such standard money-management reports as Mobius and Russell. Monthly statements from Brown & Company, a Boston-based discount brokerage house owned by Chase, brought clients up to date on their stock holdings. But it was harder for them to find out how money placed in private deals was faring. Any questions along those lines, according to former employees, were answered only by Giacchetto.

Moreover, there appeared to be no rhyme or reason to the private deals Giacchetto favored. Katie Ford, the wife of André Balazs and president of Ford Models, Inc., sought a few investors for her business, as did the publishers of the downtown Manhattan publication Paper. Giacchetto put his clients’ money into both, and Paper ran a prominent interview with him without disclosing that he was an investor. He also promised Tom Pickens, the son of legendary corporate raider T. Boone Pickens Jr., that he would raise $50 million for the Pickens Capital Fund, a project to buy up water utilities in southern towns and privatize them. He managed to raise only $5 million, and when it became apparent that the fund was not really liquid, Giacchetto’s clients’ moneys were converted into bonds, which were not paid when they were due, on December 31, 1999, but were extended to January 31, 2000. By late February they had still not been paid. One of those waiting for his money from Pickens Capital is artist David Salle. A person close to the situation says that shortly before the bonds defaulted Salle gave Giacchetto approximately half a million dollars realized from the sale of his loft to invest, and Giacchetto put the money into Pickens Capital. Did Giacchetto put Salle’s money into a deal he knew was failing? He insists that he did not. Today, Giacchetto distances himself from the project and says, “It concerns me that technically it is in default.” He adds that after seeing the latest figures from Pickens, however, “it gives me confidence that there are considerable assets here.”

The largest Cassandra loss was in Iridium, a now bankrupt global satellite phone network backed by Motorola, which many other money managers also took a bath on. The company’s bonds were among several possible deals presented for Giacchetto’s consideration by Soledad Bastiancich, the 34-year-old former investment broker at Allen & Company whom Giacchetto had hired in 1997 to be his senior vice president, and Giacchetto bought millions of dollars’ worth of them when they were selling at nearly $100. (Today they are almost worthless.) One longtime Hollywood client said it was “unconscionable” that he was not consulted before Giacchetto bought him $40,000 worth. Other well-known clients lost much more—hundreds of thousands of dollars—in Iridium. “I bought Iridium in part because it was backed by Motorola and was underwritten by Chase Bank, and it turned out to be a disaster,” Giacchetto says. “Like 500 other money managers in America, I believed it to be a good value. That was not in any way outside of what I would have bought for these clients. So I wouldn’t have talked to them.”

Perhaps the most controversial deal of all, though, was Giacchetto’s rescue of Paradise Music & Entertainment, which ended up involving one of the most complicated figures in his life, Jay Moloney, the former CAA agent and Ovitz protégé who committed suicide last November at the age of 35. According to Bryan Lourd, “Jay was a Pied Piper,” whose approval and contacts were invaluable to Giacchetto. The two met through Marc Glimcher, the scion of the PaceWildenstein gallery family. Moloney took an instant liking to Giacchetto, gave him his money to manage, and introduced him to Michael Ovitz and to talent manager Rick Yorn, who inherited Moloney’s former client Leonardo DiCaprio. At the time, Yorn was living with Pulp Fiction executive producer Stacey Sher (now a business partner of Danny DeVito’s), and they too became Giacchetto’s clients. Along with producer Michael Besman and casting director Margery Simkin, these people recommended him around. He was clearly in good company. “In those days,” says entertainment reporter Josh Young, “if you’re hot, you want Yorn to baby-sit, Moloney to make your deals, and Dana to manage your money.”

Moloney’s anointing of Giacchetto in the early 90s—which included inviting him on a rafting trip on the Colorado River in 1995 with a group of 20, including André Balazs, CAA agent David “Doc” O’Connor, and Jane Pratt, currently editor of Jane magazine—coincided with the rise of a group of Moloney’s friends, all of them in their late 20s and early 30s, who went on to become successful in entertainment and publishing. Many of these also became clients of Giacchetto’s. “He hit a group of people at a time young Hollywood was first making a little bit of money,” says one of the group. “He built up networks by acting like a young big shot from New York, then took his Hollywood connections back to New York—he leveraged both ends so brilliantly.”

Meanwhile, Moloney started to fall apart from manic-depression, which he attempted to erase with cocaine. In 1996 he began to spend more time in rehab than he ever had doing drugs, and during this time Giacchetto continued to hold his money. In November 1997, while Moloney was staying at the Hazelden rehab center’s halfway house in New York, he called Giacchetto with an urgent plea: he said a drug dealer was threatening him and he needed $6,000 immediately. Without calling anyone else first, Giacchetto personally delivered the money. Moloney took it and went on a four-day drug binge, ending up in a hospital on Long Island after a suicide attempt. Those closest to Moloney have never forgiven Giacchetto. “To me he tried to kill Jay. In fact, he almost killed him,” says Moloney’s mother, Carole Johnson. “I told Jay I was going to call Dana, but Jay defended him and said, ‘Don’t blame Dana.’ … After that, I just wrote Dana off.”

Giacchetto’s explanation is that he had no power to deny Moloney’s request; Moloney had the right to demand his money, which came from his account with Cassandra. “I didn’t have the legal ability to say no at that time. It wouldn’t have mattered. Jay wanted the money; he had access to his funds. I felt horrible about it, but I don’t feel I did anything that I wouldn’t have done for someone I loved and cared about. I don’t think I was an enabler with Jay. I tried everything to help Jay.”

As a result of this episode, Moloney’s family and friends moved to put his money into a trust which he could not get at without permission. Moloney agreed and wrote Giacchetto a formal letter asking for an accounting of his funds, which he wanted transferred to the trust. His holdings were both in art and in funds held by Cassandra—no one knew exactly how much, but between $2 million and $3 million. According to the trustees and their accountant, months went by without their receiving the paperwork. Jerry Chapnick, Moloney’s business manager and also a client of Giacchetto’s, was enlisted in the cause, but to no avail, according to the trustees. They claim Chapnick stalled; Chapnick, however, maintains that he complied with all their requests “promptly.”

“Irregularities came up in the beginning, figuring out what resources Jay had left besides art,” says Moloney’s mother, who administers her son’s estate. “The trustees said, ‘Where’s the money?’ And Dana said, ‘I don’t know. It’s here, it’s there.’ It was a battle back and forth until they got to settle and Dana gave them a check, not on Brown & Company for stock—instead, it was a Cassandra check Dana wrote.”

The trustees discovered several private deals which Giacchetto insists Moloney knew about—among them, $25,000 to Ford Models and a contribution to Pickens Capital that originally appeared to be $100,000, then $300,000, then, according to a Cassandra document the trustees saw, $669,000. When they double-checked with Tom Pickens, they learned that he was reading the total off the same document that the Cassandra Group had provided. Furthermore, according to those involved, a Pickens employee, Rusty Muñoz, told them that the delay of payment was due to a request from Giacchetto that Moloney’s original investment into Pickens Capital be backdated—a request Muñoz told them he had refused. Today, Muñoz says he does not recall any backdating request, and Giacchetto denies it. (Muñoz does recall Giacchetto’s promising to raise $50 million for the fund, however, and raising only $5 million.) Finally an accord was reached—Giacchetto gave the trustees a check for $600,000. “Dana made a settlement,” says Carole Johnson, “and then calls back and says, ‘I think I overpaid. The whole thing is a mistake.’”

Johnson continues, “I don’t know how anyone can be that sloppy—it sounds peculiar to me—in that business. If it was a movie producer, I’d say fine, but a stockbroker? No. If an accountant can’t tell me how much I spent the last month, and can’t tell me how much I have in my account, something’s wrong.” Giacchetto pleads total ignorance of Johnson’s misgivings about the $600,000 payment: “I don’t think that’s accurate. I think there’s some confusion. I think it was settled.” Moreover, he says that he had very little to do with his clients’ investments in such projects as Pickens Capital. “They were basically deals that were done between the principals but facilitated by our firm.” Yet several clients say that they never would have known about or invested in Pickens without Giacchetto’s enthusiastic endorsement. (Tom Pickens did not return calls for comment.)

Moloney was never apprised of the difficulties his trustees say they had with Giacchetto. He and Giacchetto continued to remain close, and Giacchetto said he wanted to help his old friend get back to work. In short order, he thought he had found the perfect vehicle for him.

When Giacchetto became involved with Paradise Music & Entertainment, it was a fledgling company consisting of several previously existing small businesses—a creator of advertising jingles and TV and radio scores, a video-production house that did music videos, and a musical-artist management company. Paradise began operating in October 1996 and went public three months later, raising about $5.5 million. The cash quickly disappeared; much of it was spent launching a new record label called Push. The cash crunch was so bad that Paradise couldn’t pay its New York landlord on time. In late 1998, NASDAQ threatened to delist the stock, and the company’s outside auditors expressed serious doubt about its ability to survive “as a going concern.”

Paradise’s savior arrived in December 1998 in the form of Dana Giacchetto. He tried to interest his partners in the Fund in an investment in Paradise, but they turned him down. He also tapped his other major source of capital, the portfolios of Cassandra’s largest investors. In mid-December, he invested $2 million of his clients’ money in Paradise stock, buying at $1 per share.

Many Cassandra clients bought in: Jerry Chapnick recommended Giacchetto to his clients Affleck and Damon, and they each bought 75,000 shares. From then on they were known as Giacchetto’s clients. Also buying in at $1 a share were actors Cameron Diaz, Benicio Del Toro, and Lauren Holly; artist David Salle; producer Stacey Sher, casting director Margery Simkin, CAA executive Michelle Kydd, screenwriters Akiva Goldsman and Richard LaGravenese; musicians Jakob Dylan and members of Phish; and David Kuhn, the current editor in chief of Brill’s Content magazine, who bought 25,000 shares. Soledad Bastiancich, who played a role in lining up investors, herself bought 15,000 shares.

The Cassandra Group claimed in S.E.C. filings that it had bought the shares purely for investment purposes. Although Cassandra would install three new Paradise board members, including Bastiancich, it claimed to have no plans for any extraordinary transactions, such as mergers or acquisitions, and no plans to change the management of the company. In spite of that statement, Paradise was dramatically transformed in the months following the Cassandra investment. Giacchetto signed on as a consultant to the company, to be paid with 200,000 shares and warrants to buy another 800,000 shares at varying prices. Since Giacchetto also had the right to vote his clients’ stock, he was by far the most important investor in the company and therefore had enormous influence over its stock.

Jesse Dylan, one of Cassandra’s representatives on the Paradise board, was named chairman of Paradise in April 1999. Dylan, who was well thought of as a TV advertising director, then sold his two video-commercial businesses to Paradise for a million shares of Paradise stock. A major reason Dylan entered the deal, says a Paradise board member, was that Giacchetto promised him $40 million of the $100 million in the Chase fund—an amount Giacchetto’s Chase partners said it would have been inconceivable to put in any one place. Even more dramatic was the announcement of who would become president of the new Paradise: Jay Moloney.

Moloney had not held a job in more than two years, and although he was clean he was still extremely fragile. Ovitz, Moloney’s original mentor, was dead-set against the move. He implored Moloney not to accept the position, and Giacchetto not to insist on his doing so. But Giacchetto thought it would be good for Moloney to go to work someplace “under the radar.” Ovitz was claiming that there would be too much stress in a start-up without much cash flow. Within four weeks, Ovitz told friends, Moloney was so far down he couldn’t get out of bed.

In May, in order to lure new investors, Paradise announced that it was going to raise $8 million. By then the stock had begun to rise, trading between $4 and $5 a share. The cachet of the famous names involved was clearly part of the draw, and certainly the announcement that $8 million was being raised created a floor to attract other investors. A list of investors was included in Paradise’s S.E.C. filings, and some of the prominent names even popped up in Daily Variety. Affleck and Damon, among others, were upset to have their names used in this way. But Giacchetto failed to see that he was alienating his base. Furthermore, he once again asked the Fund to back Paradise.

“I brought it back and said this is really a compelling situation,” says Giacchetto. “I thought Jay was the most talented executive in Hollywood, even with his problems, and I didn’t put him in there for some nepotistic act. I thought he’d be the best, and he and Jesse would run it. So I went back to the bank and said this is a ‘10’ deal. Their response was as it was to a lot of things—this was a conflict, because I managed people’s money. [But] this is what I thought should be the confluence.”

In the back of his mind, it seems, Giacchetto envisioned Paradise as evolving into a studio of sorts, where his biggest clients, especially DiCaprio, could make movies or videos and create the kind of “equity” and “value” that Giacchetto had always talked about. “It could grow, be aggressive,” he says, “grow into a big entertainment company.”

Cassandra arranged for all of its clients who were interested to buy new Paradise stock at $4.25 a share. New investors included actors Ben Stiller and Tobey Maguire as well as artists George Condo and Ross Bleckner. According to Bleckner, “They were going to develop entertainment properties both new and old: films, music, video —whatever.” Leonardo DiCaprio bought 50,000 shares. But even with DiCaprio in, Giacchetto was not able to raise the $8 million. It took him about three months, until July, to raise just over $4 million. Some Cassandra clients who had paid $1 a share the previous December did extremely well by selling out at a profit later in the year. Other clients were not so happy: they told Cassandra that they had not wanted any Paradise stock but found it in their accounts anyway.

One entertainment attorney, who said he had a specific agreement with Giacchetto not to make trades for him without consultation, was irate. “In August, I saw out of nowhere he bought me a load of Paradise Music. That made me crazy. He had sent me the prospectus. It was not a stock I wanted in my portfolio.” The lawyer suspected that Giacchetto was desperate. “He really was looking to get rid of the stock.”

Another money manager, who had reviewed the offering for some Cassandra clients, had the same experience with someone who ignored his advice and bought the stock. “All this stock was accumulating, and he was selling them a company with absolutely nothing in it.” He concluded, “The only way I avoided a legal battle is the stock ramped up one day to 7 and they were able to get [my clients] out.”

When news spread on the Internet that one of Paradise’s founders had composed the Pokémon CD, the stock traded heavily for two days and shot up to $9. At that point, a third client told me, Giacchetto called him to say that he was going to sell half of the client’s holdings in Paradise. But he never did. “Then I heard he had sold for someone else at 9. He told me and my bookkeeper he couldn’t sell the stock because he didn’t have the certificates.” But it was unclear why the certificates were even needed to make a trade. Giacchetto claims that, in this instance, as in all his 11 years as a money manager, “I did everything by the book.”

More recently Paradise, under new management which Giacchetto was responsible for installing, has reduced its losses substantially and is currently gaining important contracts. But the stock is hovering around $2 a share, and many Cassandra clients are still holding it. “The story is not over yet,” declares Giacchetto, who through Cassandra still controls a substantial percentage of Paradise. “It’s a long-term investment.”

He tells me, “If you’re suggesting that there were famous people in the stock [and] that’s why it ran up and those people benefited, it’s just not true. A lot of my clients are famous, and some made money in the stock and some would lose money in the stock. It was not being manipulated. We bought the stock. We disclosed who the clients were. We sold it when the clients wanted to sell it. I still believe in the stock. Everything I did was copacetic.”

Questions about Giacchetto had been raised before. In 1994, when Moviefone—the film phone-in reservation guide subsequently bought by AOL with AOL stock then worth $388 million—went public at $11.50 per share, he asked that Cassandra be included among the first buyers allocated shares. When the stock promptly began to fall, he informed the stunned broker who called in his trades that he wouldn’t be paying what he owed. As a result, those offering the I.P.O., who knew Giacchetto socially, were left holding the bag for more than $100,000. It was not until about two years later, when Giacchetto realized that he was being bad-mouthed for his behavior, that he paid up on “reneged trades” for five clients, including Michael Besman and Amir Malin, currently the head of Artisan Entertainment. “Those were the accounts that were in dispute, and obviously they were settled,” Giacchetto says today. “These clients did not want the stock; I would do whatever the client asked me to do.” But Malin had told him not to buy the stock in the first place.

At times, Giacchetto’s favored clients did not even have to worry about losses. “If you call and say, ‘You should have called me on that,’” says commercials producer Mark Hankey, a longtime friend and satisfied client of Giacchetto’s from Boston, Cassandra would “make it right.” Generous to a fault, Giacchetto gave another client of modest means, photographer Nubar Alexanian, an outright gift of $20,000 when he had to care for his oldest sister, who was dying of cancer. Giacchetto liked introducing his clients to one another; if they got together on projects, he said, he had more money to invest. For example, he introduced Hankey and Alexanian to the rock band Phish. As a result, Hankey was able to produce a documentary film, and Phish appeared in a book Alexanian published about music. Explaining his approach to me, Giacchetto says, “How can I help you meet people you want to meet in that community? My job is to make you as much money as possible.”

Even some of Giacchetto’s severest critics concede that he did not set out to line his own pockets at the expense of his clients. In fact, for his most spectacular networking coup, he received absolutely nothing.

In 1998, when Michael Ovitz was reeling from his short and unhappy turn as president of Disney, Giacchetto helped bring him together with the young elite of Hollywood, including Rick Yorn and his sister-in-law Julie. Ovitz wasted no time in luring the Yorns, along with DiCaprio, Diaz, and Minnie Driver, to his latest venture, a move that caused enormous resentment both in Ovitz’s former agency, CAA, and in the Yorns’ former employer, Industry Entertainment. Though today both Rick Yorn and Ovitz scoff at the idea that Giacchetto was anything more than “a cheerleader” in the formation of their company, AMG, those observing the courtship—from SoHo dinners to cruises on Ovitz’s yacht—believe otherwise.

“Would Leo get along with Mike? Everyone was worried,” says one close observer. Giacchetto had enormous influence over the sensual young actor—he even read scripts for him. “Being with Dana the last half of ’98 and most of ’99, you were at the center of power. If you wanted to get Leonardo DiCaprio in a movie, you’d have to go through Dana. If you wanted to talk to Leo, call Dana’s house—he lived there. All those people—Tobey Maguire, Q-Tip, Alanis—stayed there. And Dana would have kept them if he’d just invested in blue-chip stocks and never mentioned them in the press.”

Last year, Ovitz declared in Manhattan File magazine that Giacchetto was not only a financial adviser. He was “a life adviser.” Last July, Yorn said to CNN, “He’s an incredible money manager and a savvy assessor of artistic talent.” Recently, Yorn has acknowledged only that Giacchetto was friendly with DiCaprio for a time but has said that he had no involvement in his career.

In October 1998, Giacchetto became partners with Jeffrey Sachs and Sam Holdsworth in Cassandra-Chase Entertainment Partners (the Fund), a $100 million venture. Sachs, who was trained as a dentist and had served as a health-policy aide in the administrations of New York governors Hugh Carey and Mario Cuomo, had been a financial consultant and lobbyist for the last 10 years. At 46 he was unmarried and gravitated toward glamorous individuals. Rooted in New York Democratic circles, he coached Billy Baldwin on politics and befriended both John Kennedy Jr. and Christopher Cuomo. His P.R. man, Ken Sunshine, soon replaced DiCaprio’s longtime representative, Baker, Winokur, Ryder (BWR).

Sam Holdsworth, 46, was the former publisher of Billboard magazine and a freelance investor. He had worked with Giacchetto on the deal to sell the Sub Pop record label. Lately, he had been intensely involved in backing and promoting Global Source, a troubled financial-information service with no Internet capability, which became obsolete and lost more than $3 million, much of it coming from Giacchetto’s clients.

Sachs had made the original contact to create the Fund with his friend Mitchell Blutt, now 43, a former practicing doctor and the second-in-command at Chase Capital Partners. Giacchetto and his partners had no authority to use money independently—all investments had to be approved by Blutt and the bank. Giacchetto and Sachs soon became close friends. In fact, Giacchetto had given Sachs rent-free office space for the previous year as they worked to get the Fund off the ground. In the process Giacchetto hired a number of Sachs’s cronies to work both for Cassandra and for the Fund, and he paid their salaries. He alleges in his lawsuit that these services totaled $600,000.

For example, Giacchetto hired Robin Chasky, Sachs’s 46-year-old cousin, to manage the office, and she did her best to keep track of Giacchetto’s deals. Sachs’s good friend Christopher Cuomo became Cassandra’s in-house counsel. Almost immediately, one observer says, Sachs shed his Dockers for Prada and Blutt his Wall Street wear for tight jeans as they went out on the town with Giacchetto in New York and Hollywood. Soledad Bastiancich was not involved with the Fund. The ambitious Yale-trained lawyer was the girlfriend of another of Sachs’s friends, John Howard, a seasoned Bear Stearns investment banker who had done a deal with Giacchetto and had brought her to his attention. She soon became alarmed at what she considered Giacchetto’s wild spending, slipshod office administration, and bookkeeping in the Cassandra Group.

Christopher Cuomo, now a 20/20 correspondent, spent less and less time at Cassandra as he pursued his TV career. He says he was hired to do deals and to be Giacchetto’s personal lawyer, to try to get clients who had received generous loans from Giacchetto to pay up. “Figuring out what to do with this stuff was so convoluted and confused,” Cuomo says. Worse still, much of the paperwork regarding these loans was nonexistent—everything was in Giacchetto’s head. “I would call and say, ‘Hey, make the payments. Do you owe Dana money?,’” Cuomo recalls. “They’d say, ‘Let me call Dana,’ and I’d never hear another thing about it.”

For example, Jerry Chapnick not only handled in common with Giacchetto Affleck and Damon but also was a client of Cassandra. Chapnick received a $100,000 loan from Giacchetto against the collateral of his portfolio. When I brought the subject up with Chapnick, he denied that he had ever received such a loan. After a moment’s pause he suddenly was able to recall the transaction, insisting, however, “I paid it back in full.”

Giacchetto was often out of the office, working on the Fund, or out late at night “maintaining Leo,” in the words of one executive, and he frequently picked up checks for expensive dinners for 15 or 20. During the end-of-year holidays in 1997, he and Sachs led a group of 30—including DiCaprio, Morissette, Jesse Dylan, and Christopher Cuomo—to Havana. “I really think in this community the lines between business and social are blurred—it’s delicate,” says Giacchetto. In the entertainment community, he adds, business “is not done in a boardroom; it’s done at 11:30 after a rock show, or in an airplane, or in the subway, or in an art gallery.… I needed to become part of the fabric of the community.”

In a letter Bastiancich wrote to Giacchetto in March 1999, she alleged that his travel and entertainment expenses for the previous year had been more than $550,000 and that the Cassandra Group “has had several hundred thousand dollars worth of trade errors during the past couple of years.” Other problems arose when Giacchetto, always seeking to ingratiate himself, would allegedly tell clients that they had made more money than their monthly statements eventually showed, and the clients would complain. Giacchetto insists nothing untoward was going on. “There is absolutely no hanky-panky, and there never has been.” But at times these situations got heated. British movie director Brian Gibson, for example, threatened legal action; a settlement was reached, but he left Giacchetto.

Blissfully unaware, probably thinking those he trusted were handling everything back at the office, Giacchetto had spent two weeks in January 1999 visiting DiCaprio on the set of The Beach in Thailand. He had big plans for yet another worldwide merchandising deal featuring DiCaprio and other young stars, which he would run. “I do not want to steal your business from you nor do I want to subvert your power in any way,” Bastiancich said in her letter. Then she suggested that Giacchetto might not really want to “actively trade anymore,” and proposed that she become president of the Cassandra Group and that Giacchetto move up to C.E.O. She also proposed that if her salary were reduced she might be granted a small share of the profits or equity in Cassandra. “When I was away in Thailand,” says Giacchetto, “I thought everyone was working on my cause in the office. When I came back, I realized they didn’t feel that way.”

In the third week of January, to allay her fears, Bastiancich got Giacchetto’s permission to have a securities attorney and forensic accountants come into the office and look at the Cassandra Group’s books. In the words of a close observer, “Soledad was having her Al Haig moment: ‘I’m in charge here.’” She called a meeting and, according to one participant, brought up the possibility that after this accounting Giacchetto might be forced to leave the securities business. (Bastiancich declines to comment on the meeting.) When the expensive accounting was finished two months later, however, no fraud or other criminal wrongdoing was found. But Giacchetto was advised that he needed to streamline his procedures, that he should stick to blue-chip investments, and that he should be careful not to commingle his clients’ funds—that is, he should not mix clients’ assets with the firm’s assets or with other clients’ assets.

Sachs and Holdsworth claim that since Giacchetto was having cash-flow problems they lent him $500,000 and $450,000, respectively, to rectify any mistakes uncovered by the audit. Bastiancich left the Cassandra Group after pressuring Giacchetto to give her a six-figure bonus, which she never received.

According to the defamation lawsuit Giacchetto filed against Sachs, Holdsworth, and Egan, he was supposed to give only 25 percent of his time to the Fund; Sachs was supposed to give 50 percent of his time to it, and Holdsworth, 75 percent. There was no question that Giacchetto’s contacts had fueled the creation of the Fund, but almost from the beginning everything that could go wrong did.

The one big investment the Fund took the lead on, Digital Entertainment Network (DEN)—which Giacchetto had little to do with—quickly became an embarrassment. DEN was supposed to provide on-line shows for the 14-to-24-year-old market. Its chairman, 39-year-old Marc Collins-Rector, and his two co–executive vice presidents, 18-year-old actor Brock Pierce and 24-year-old Chad Shackley, had offices in the San Fernando Valley mansion that had once belonged to jailed rap producer Suge Knight, where they threw outrageous parties. The salaries of the company’s top eight executives, excluding the three founders, totaled $5 million. Last fall, on the eve of the launch of their I.P.O., on which investors, including executives at Microsoft and Lazard Frères, hoped to raise $75 million, news leaked to the press that Collins-Rector had been forced to settle a lawsuit in which he was accused of sexually molesting an under-age boy. Collins-Rector resigned. Then the inflated salaries were published, the I.P.O. was canceled, and the Fund lost $6.5 million of the $20 million DEN had spent, with no revenues in return. In February, the renamed Chase Capital Entertainment Partners announced that it was spearheading yet another investment in DEN, this time for $24 million.

Meanwhile, Giacchetto got more and more frustrated as his partners kept nixing deals he came up with. The bank also brought in another partner, Robert L. Egan, now 37, an investment banker with no entertainment experience. According to Giacchetto, Egan told him, “You’re just trying to help your clients.” Giacchetto says he was astounded. “Of course I am! That’s why I created the Fund.” He was turned down cold by his partners and the bank after bringing Ovitz in for a preliminary discussion on a movie-distribution deal and after proposing a Danny DeVito Internet project. “And I was like ‘What the hell are you doing?,’” Giacchetto recounts. “‘So you use my client base, in my name, to get this access to everyone in the entertainment business. I don’t understand—this is why you [created the Fund].’” He concedes, “So we were going in different paths. We were diametrically opposed.”

By last summer, Giacchetto’s partners say, they were getting fed up, scared that his antics would undermine the Fund. Giacchetto couldn’t stop talking—to the press, to one client about the business of another, to his colleagues in terms many of them thought were wildly exaggerated. How many plates could he keep spinning before they and he both crashed? Colleagues became concerned about his manic behavior. “I would say the press is his drug. He could not resist it,” says his former partner Jeffrey Sachs. “It was a combination of Leo and going to work with Chase—the biggest, most respected bank in the world and the biggest movie star in the world.”

According to Giacchetto’s lawsuit, in August 1999 he was given a talking-to at the Royalton hotel in New York by Chase honcho Mitchell Blutt, who informed him that his partners wanted to distance the Fund from the Cassandra Group because clients were finding it difficult to distinguish between the two. In September, Giacchetto’s partners moved to a new space two blocks from the Cassandra offices, taking all the files with them. Within a week, Sachs demanded that Giacchetto resign from the Fund, which he refused to do. At the end of October, Sachs and Holdsworth sent a letter to Giacchetto, according to his suit, removing him from the Fund and eventually making him eligible for only 8 percent of the business.

Giacchetto has a hard-core group of supporters who feel that the negative publicity that has befallen him was the result of an orchestrated hit. Several days before a December 6 story appeared in Daily Variety announcing that as many as 17 of Giacchetto’s high-profile clients were defecting, there were whispers in the entertainment community that this would be a “career-ending story” for Giacchetto.

Wanting to remain loyal, yet ready to be quoted only anonymously, Giacchetto’s friends say they are willing to overlook his failings. “There is a whole group of people who feel very, very supportive of Dana,” says a prominent New York figure. “All of us acknowledge his shortcomings, his lack of finesse, lack of discretion, and the name-dropping thing. With Dana I never found it obnoxious. He was so out there you don’t hold it against him.” Another Giacchetto loyalist adds, “Dana is going to pay for everybody’s sins.”

Moreover, some people who dealt closely with the Fund took Chase’s concerns as a kind of joke, often mentioning what a good time Giacchetto had shown Mitchell Blutt. “People say that Chase are fools for giving so much money without doing due diligence,” comments one executive. “But nobody cared, because they just wanted to go to parties.” Because of pending litigation, Chase declines to comment.

One of the most baffling aspects of the controversy is this: If Dana Giacchetto is guilty of malfeasance, why hasn’t anyone come forward to condemn him publicly? So far, by Hollywood wisdom, the embarrassment factor would seem to outweigh any desire for justice or revenge. After all, who wants to admit to having been naïve or manipulated when it comes to his or her money? In order to prosecute, you need victims, and the rich and famous don’t like to be considered as such. In the end, however, their reticence may not be much of a deterrent.

“I have one word for you,” says a lawyer knowledgeable about the case. “Subpoena.”

No Comments