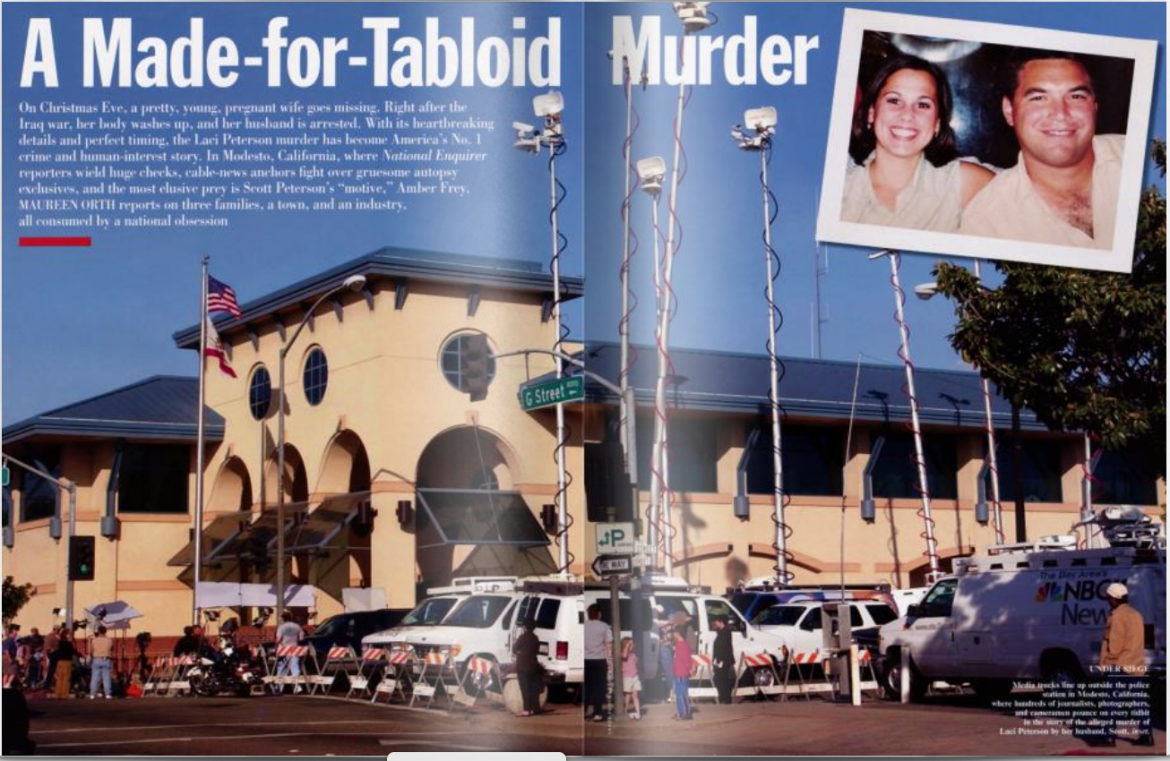

Vanity Fair – August 2003

Few in the horde of journalists covering the Laci Peterson murder case in Modesto, California, have ever set foot in Gervasoni’s bar, though it is just a few blocks from the Stanislaus County Courthouse, but this friendly, 50s-style saloon has become the hangout of choice for two of the story’s most prodigious propagators, David Wright and Michael Hanrahan of The National Enquirer. By liberally spreading cash all over this community of 203,000, the dapper, silver-haired operators, both in their 60s, have broken many of the scoops claimed by better-known reporters and newscasters weeks, even months later. In an increasingly frenzied and downscale tabloid-news era, Wright and Hanrahan finally see everything coming their way, for, if the weekly tabloids were once considered beneath contempt by the Establishment press, today they are must-reads for everyone in the media. Conversely, the highly organized pageants of grief and speculation that big criminal cases have become, particularly on cable television, are the perfect petri dish for Wright and Hanrahan to develop their stories in. “Every morning you wake up and think, What can I turn today?,” Hanrahan, a former reporter for the New York Daily News, tells me as we sit in Gervasoni’s on May 29. Wright, a Brit and a 27-year Enquirer veteran, adds, “The Peterson story has broken perfectly. The tabs kept Laci going during the Iraq war, and as soon as the war finishes, her body washes up.” Wright says he hopes that Judge Al Girolami will issue a gag order on the case, for then the tabloids would be in an even stronger position to offer money to entice information out of local people. “We love gag orders—they’re the best we can hope for.”

So far money has definitely talked in Modesto, and even if someone turns it down, there’s usually somebody else already in line. Willie Traina, for example, the previous owner of the Petersons’ ranch-style house, told me that he had twice been told that the tabloids were willing “to pay me $150,000 at a minimum” for pictures of the interior of the three-bedroom dwelling, in which Laci was allegedly murdered, but that he had refused. No problem: the Enquirer, which has local private investigators on its payroll and keeps at least two reporters in Modesto at all times, found another source and published the pictures in May. Laci’s father, Dennis Rocha, sold his story along with family pictures to the Enquirer’s sister publication Globe—which outbid the Enquirer—for $12,000. Wright and Hanrahan also do the old-fashioned kind of legwork that younger reporters often shun in favor of downloads from the Internet, and both of their methods have paid off, so to speak. According to Steve Coz, editorial director of American Media, Inc., which publishes The National Enquirer, Globe, and Star, every Laci Peterson cover has increased sales of each of the three weeklies by as many as 300,000 copies. After the Enquirer gleefully reported in May that it had “penetrated the ongoing investigation,” the Modesto Police Department began an internal scrutiny of the force. But, as Hanrahan explains to me, “if you say there are a half-dozen cops working on this … which one speaks to us, that’s not the way it works. Cops all have girlfriends, sisters, uncles, mothers.”

While giant satellite trucks outside jockey for curb space to broadcast every last tidbit of leaked evidence in the case, Hanrahan greets owner Gary Gervasoni as an old friend and orders his first vodka-and-soda at four p.m. This is a popular spot with locals; before the murder, Laci’s stepfather, Ron Grantski, used to drop in. And since the Peterson case, like the O. J. Simpson and JonBenét Ramsey cases before it, has everything to make it the No. 1 human-interest reality-TV soap opera in America—the pretty, young, pregnant wife goes missing on Christmas Eve, her handsome husband’s girlfriend reveals the affair they’ve been having, he heads south, the wife’s body and that of her unborn baby are later discovered a few miles from where her husband claims he was fishing when she disappeared, he dyes his hair and is arrested carrying $10,000 in cash—Gervasoni’s is just the sort of connected place the Enquirer reporters favor to find out which doors to knock on. They also trawl certain restaurants and churches. Today a tough-looking construction worker in shorts and sneakers pops in to ask whether something he has come across is worth anything. Hanrahan says the man has contacted the Enquirer, which routinely pays $500 per tip, because he believes he has uncovered a satanic mural in a house he is remodeling. Hanrahan leads him over to a booth, pulls a notebook out of his back pocket, and starts writing.

Anything smacking of satanic cults is big in Modesto these days, ever since Mark Geragos, Scott Peterson’s high-powered Los Angeles lawyer, not only promised to find the “real killers” of Laci and the baby she planned to name Conner but also announced that he was looking for a brown van seen in Laci’s neighborhood that had some connection to a satanic cult. He said he was also trying to locate a reluctant female witness who had valuable information. Whether the woman was part of the van story was not made clear at first. The Enquirer reporters, who are convinced of Scott Peterson’s guilt, tell me that Geragos is “all smoke and mirrors.” Globe had run a story earlier saying that the police had already checked out the brown van. As for the mysterious woman, she had contacted Globe as well as the police, and her ex-husband had told that tabloid that she had a history of mental illness and suffered from multiple-personality disorder. Nevertheless, because the prosecution has played the case so close to the vest, the defense has had ample opportunity to cast doubt on Peterson’s guilt by filling the void with alternative scenarios, and the strategy has worked, particularly since cable news channels have to fill the air 24-7.

That same day, May 29, about one p.m. eastern daylight time, NBC chief legal correspondent Dan Abrams had excitedly announced a bombshell on MSNBC: he had “exclusively obtained” a partial copy of the addendum to the sealed report on the autopsy of the remains of baby Conner—the authenticity was later confirmed by official sources to the Associated Press— and could reveal that the fully formed fetus had been found with a piece of plastic tape wound around its neck one and a half times, “with extension to a knot near the left shoulder.” There was also a “postmortem tear” going from the baby’s right shoulder to the right lateral abdominal wall. Up until then the baby’s separation from Laci had been assumed to be the result of “coffin birth,” where the built-up gas in the decomposing body of the mother expels the fetus, but now here was the tantalizing idea that the baby may have been cut out of Laci’s womb.

The combination of a knife and a satanic cult sent the media pack racing, and 30 minutes later the cult idea was being discussed on Fox cable by Linda Vester and Rita Cosby, who gave no credit to Abrams. Meanwhile, Abrams re-appeared with a lawyer who scored the case, as it now stood, like a tennis match: “Advantage defense!” At three p.m., Pat Buchanan and Bill Press abandoned national politics in order to focus “almost exclusively on the breaking news first reported here on MSNBC by Dan Abrams.” By then the prosecution had made a complete U-turn, and at four o’clock CNN announced that the prosecution had sent out a press release saying it would request that, due to “numerous leaks to the media today,” the judge make public the full autopsy report. At five p.m. both Wolf Blitzer on CNN and Lester Holt on MSNBC discussed the feeding frenzy. MSNBC editor in chief Jerry Nachman characterized the story as “crack for us in the business … we can’t stop ourselves.”

His words proved prophetic. Geraldo Rivera, who had appeared two hours after Abrams to say that he also had the full addendum, was back at eight p.m. on Bill O’Reilly’s show, going out of his way to pooh-pooh Abrams’s scoop. He said that the addendum did not support material “spun earlier by sources friendly to the defense.” “This cable thing is like Fleet Street in the old days,” David Wright told me. “One paper would have a scoop, and the other papers would trash it but be free to follow it up.” He was right: it was all Laci all the time throughout the evening—on Chris Matthews’s Hardball, Hannity and Colmes, Larry King Live, Scarborough Country, and On the Record with Greta Van Susteren—and into the next day, May 30, when Good Morning America announced that ABC had “seen in full exclusively” the autopsy report, and Charles Gibson noted that it indicated that Laci Peterson’s cervix was closed, adding that he had been assured by an expert that “this can happen.” Soon local newspapers in California were quoting coroners closer to home, who said that the plastic tape was most likely debris which had caught around the baby’s neck, and that the cut may have been made by a boat propeller.

That night the Enquirer reporters introduced me to a local criminal-defense investigator sitting at the other end of Gervasoni’s bar who was not working for either side in the case. Alan Peacock gave me his business card, which read, “Fruits and Nutz,” a play on Modesto’s largest cash crops—not counting sensational criminal cases such as the murder of Modesto native Chandra Levy in 2001 and the slaying in Yosemite National Park in 1999 of a mother, her daughter, and a friend, whose killer became the object of a search in Modesto. Absolutely free of charge, Peacock gave me his rundown on the defense’s satanic-cult theory, and it’s proving remarkably accurate as the story has played out since.

Peacock explained that 10 years ago he had worked on a murder case in nearby Salida involving members of a satanic cult. They were all convicted and are behind bars, but one could argue that individuals from the group are still around. “If I’m a criminal-defense attorney, I’m going to get someone to sell the public, to get people to look a different way. If I can identify a suspect or a vehicle that law enforcement doesn’t want to deal with or account for, I can put out a call for the occupants of a brown vehicle.” In fact, there were reports of a brown van in Laci Peterson’s neighborhood at the time she disappeared, and the police claimed it belonged to landscapers, but Peacock says the witnesses reported that the vehicle had had no lawn mowers or rakes in it and that the occupants were not identified. Peacock told me the defense had found out about these people from the police files and had figured that the police had not looked hard enough for them.

“The defense put out a call they are looking for this young woman who had floated through a rape-crisis center. She claimed she was raped by two women while the men [in a brown van] watched, 10 days before Laci disappeared. Anyway, during this process, what this woman has said, according to the defense theory, was ‘If you want to see the other part of this sacrifice, keep a close look at the newspapers and read about it Christmas Day.’ ” Peacock added, however, that she wasn’t the only woman to make such a claim. “There was a prior point in April in Merced [a town about 40 miles away] where a woman claims to have had a similar circumstance—a similar night with a similar group of people. Police wrote her off as a kook, but the defense always needs kooks.”

Peacock also mentioned that one of the van’s occupants allegedly had a tattoo on his arm—“666,” supposedly a satanic symbol—which the defense has leaked. He said that the whole idea was “to draw attention away from Scott Peterson and give the public someone different to look for—that he’s not the person who killed his wife. They are satisfied the cult is the way to go.” Since Peacock told me this, the defense has leaked more details. They are seeking a man named Donnie with a “666” tattoo and a woman who was raped and who later reportedly told a worker at a rape center that her attackers had told her she could read about the rest of the ritual on Christmas Day.

Meanwhile, the prosecution put out a press release stating that Modesto police had again picked up the brown van, checked it out at the crime lab, and found no traces of blood in it, which the woman had supposedly mentioned. Nevertheless, Peacock said he admires the way Geragos manipulates the media, and suggested that this was one half of a two-part defense strategy. If the trial takes place in Modesto, Peacock believes, after Geragos does his work on the media and proceeds far enough with the satanic-cult theory, he can sit back and let Kirk McAllister, Scott Peterson’s original Modesto attorney, take the lead. “Kirk is the one who can step in with a lot of credibility with the locals.”

Less than two weeks later, on June 12, Judge Al Girolami issued a far-reaching gag order to stanch the flood of leaks and speculations. It prohibits all involved lawyers and their staffs, court and law-enforcement employees, and potential witnesses from discussing the case or releasing any relevant documents, photos, or information.

One part of the fallout from a story of this magnitude is its impact on ordinary people suddenly thrust into the spotlight. A prize example is Amber Frey, the 28-year-old massage therapist from nearby Fresno, a single mother with a two-year-old daughter whose existence was first disclosed by the Enquirer in late January. She is the most important witness in the prosecution’s case, because Scott Peterson told her he was unmarried when they met about a month before Laci disappeared, and their affair was so intense that Frey sent out Christmas cards with the couple’s picture on them—one of the pictures the Enquirer paid dearly to acquire. For the prosecution, Frey provides the motive for Laci’s murder.

Shortly before Laci disappeared, Scott told Amber that he was a widower—he did not admit he was the husband of Laci until 12 days after she disappeared. At that time Amber—who had thought his story that he would be away in Europe for Christmas sounded so fishy that she had a private-investigator friend of hers check him out—went right to the police and told them all she knew. She also wore a wire for the prosecution, and the Enquirer first reported in May that in her conversations with Scott, which went on until his arrest, he had told her that he had not killed Laci but that he knew who had—something he never told the police.

Amber Frey is the single biggest interview a reporter could get—excepting a jailhouse confession from Peterson himself. But she refuses all offers and has received no money for her information. In February the Enquirer published semi-nude pictures of her with braces on her teeth—which she had posed for in 1999 and then signed away the rights to—and identified her as the other woman in a triangle with a pregnant wife. Because of that, her credibility in a courtroom will certainly be under attack, and she can expect to be pilloried by the defense. To provide a queenly foil for Mark Geragos, Frey has retained well-known, impeccably groomed victims’-rights lawyer Gloria Allred of Los Angeles, who sometimes makes the networks come to a studio of her choosing for the sound bites she so frequently gives out. As one lawyer put it, “The quickest way to get a broken leg is to get between Gloria Allred and a camera.”

The rare opportunity she missed was a crucial one on June 5, when Fox’s Greta Van Susteren dramatically lowered the ethical bar and invited Larry Flynt of Hustler magazine on her show to discuss the negotiations he was going through to acquire the topless pictures of Amber, which Van Susteren kept flashing with a red banner over the breasts. Referring to Frey’s work, Flynt slandered both Amber and her profession by saying that a masseuse is “just a glorified term for a hooker.” Van Susteren refused to comment to me for this article, but the next night she began her program by telling Allred, “It’s no secret I am a fan of Amber’s,” and “I imagine it’s pretty tough on her.” Equally surprisingly, Allred responded to the previous night’s vulgarity by complimenting Van Susteren: “You’re a very sensitive person to recognize this.”

Watching all this go down from Fresno was one of the most colorful characters in the story, Ron Frey, Amber’s gruff, voluble father, a 51-year-old general contractor with a fondness for tying the media up in knots. Without telling him that Flynt was going to be on the show, he says, Van Susteren’s staff had begged him to call in. He had previously called in to Rita Cosby’s show on Fox News in February to denounce David Wright when the Enquirer first published the pictures, and it was Wright who got angry that time, because he says he had not been forewarned. Cosby told me that that may be the reason Mike Hanrahan said to me about her, “I think Rita Cosby is another Jayson Blair [the plagiarist forced to resign from The New York Times in May]—I think she just copies us without quoting us.” Cosby said that was “outrageous. I don’t even read The National Enquirer,” but she later admitted that she did and that she had had Wright on her show. The food chain never ends.

Ron Frey is now on friendly terms with Wright because of Cosby’s show. The two talked by phone after their encounter, and Wright made the nearly 100-mile pilgrimage from Modesto to Fresno in an attempt to persuade Ron to ask Amber if she would accept $100,000 for an exclusive interview plus pictures of her and Scott. “She sat there and said, ‘It just doesn’t seem right.’ That brought tears to my eyes, when you see a kid do that,” Ron Frey told me during my own pilgrimage to Fresno. When I’d asked Dan Abrams if it was difficult to get access to Ron Frey, he said, “It’s like getting into Iraq.”

I have since learned that when Amber’s name surfaced last winter a number of producers and reporters, hoping to catch her visiting her dad, embedded themselves for up to two weeks at a time in Ron Frey’s 81-year-old mother’s house, where he lives. First he made some of them produce letters on their networks’ letterheads promising that they would not repeat or report anything they saw or heard there. Frey claims he still has the letters in his safe. “CBS, Diane Sawyer’s staff—they’d all be sitting here all day long,” he said. “They were here so much they know my dog’s name, my mother’s name. They would talk about my little dachshund, who is kind of smart. He dresses himself, but they never got to see that.”

“Pardon me?”

“My little dog puts his own shirt on. Larry King’s producer, after the war, called me up a while back, and she said, ‘Do you want to do the show? And your mother? And your little dog, Buddy?’ See, they know.” Frey set me straight on Amber’s supposed “makeover.” She had first appeared on-camera with no makeup, and messy, dirty-blond hair. That, he explained, was because the Enquirer had revealed her affair with Peterson, and she had to hide from the media in the ladies’ room at work until the Modesto police took her to a hastily called press conference. She did her own hair and makeup for a subsequent news conference, at which she named Gloria Allred as her attorney. That time, says her father, she was back to her normal platinum blond. Since his ordeal began, Frey has put on 35 pounds, much of it while dining out with the media. He has received more than 5,000 phone calls from reporters, on several lines. At first he had his construction workers help him answer the calls, which he carefully logs, “but they won’t do it anymore.” He adds, “I was down to one cigarette a day; now I’m back to a pack.” This admission came after he told me, “I put in nine hours of work yesterday and six hours on the phone last night answering the media.”

Frey got a lot of additional media attention after The Modesto Bee and The Fresno Bee published a letter of his to the editor in June praising the courage of his daughter as well as his son, Jason, a captain in the U.S. Army in Iraq, for doing their duty for their country. The letter prompted the Today show to float the possibility of putting Ron and Amber on a satellite phone with Jason on Father’s Day, but when Amber declined, the conversation was put on hold.

Apart from the statements Amber Frey made when she came forward and when she retained Gloria Allred, the only time she has spoken to the press was to denounce her onetime close friend Sherina Vincent for selling photos she had taken of Amber and Scott at a Christmas party to People magazine. Vincent is suing People for failing to crop a picture of her on the wall in the background of one shot and for not paying her the full $15,000 she claims she was originally offered, since one of the pictures had also showed up on Fox News and in the New York Post. “That’s appalling that she’s doing this,” Amber Frey told The Fresno Bee. “She doesn’t want her picture in the magazine, but it’s OK that she sells the photos and profits off me, Laci Peterson and her baby?”

‘Here we go—whatever it is, whoever it is.” After saying that, the tall TV cameraman standing next to me outside the Modesto courthouse the day in May when Mark Geragos made his first appearance as Scott Peterson’s counsel politely shoved me out of the way. I counted 18 cameras mounted on tripods, 3 handheld cameras, and 11 satellite dishes on the street—in other words, it was a relatively quiet day. Off to the side, however, an ambulance was at the ready, lights blinking, because word had just come out that a woman inside had fainted. All the newsmen were clearly hoping that it had been Jackie Peterson, Scott’s mother, because that would provide them with a great photo op. Jackie Peterson, who usually carries a breathing aid with tubes in her nose and who looks like an older version of Laci, had appeared frail as she entered the courthouse earlier. Suddenly the doors swung open and a flushed, heavyset lady was carried out on a stretcher. The cameras all stopped whirring, and you could hear the sighs of disappointment.

When Jackie Peterson did emerge, she said of Geragos, “God sent him our way.” Before God intervened, Geragos had been a regular on CNN’s Larry King Live, where he had declared that finding Laci’s body so near to where Scott had been fishing was “devastating” to Peterson’s case. There were rumors that the Petersons, who are well-off, had put one of their imported cars—a Jaguar—up for sale to help pay for their son’s defense. Geragos, like Gloria Allred, is a real Hollywood character; a day without flashbulbs and microphones for him is like a day without prayer for the Pope. Once hired, he immediately took charge, down to the smallest details. Even the awful tie Scott Peterson wore the first day in court with Geragos had been chosen so that he would not appear designer-slick. Though Geragos is known to be very considerate toward the media, he can also be tough with them. Sandy Rivera of NBC was once close to network Nirvana—five minutes from finishing copying the entire videotape of Laci and Scott’s wedding at the Petersons’ house near San Diego—when Geragos telephoned, heard what was happening, and ordered her to stop. Days before Judge Girolami issued the gag order, I asked Geragos if he thought the judge would do it. He laughed and said, “That would be so futile.”

Each network has a white tent, and they are spread out across the street from the courthouse like a giant media bazaar, where talking heads are simultaneously selling their wares over the airwaves. Until recently a local denizen with some radio experience would often knock on the doors of the satellite trucks and ask if they needed any man-on-the-street sound bites.

Modesto’s resources have been inordinately taxed by the TV-and-press crowd, and the city plans to ask the California legislature for money from the state—which is broke—to help bail it out. Detective Doug Ridenour of the Modesto Police Department, which has about seven detectives on the case, told me they have received thousands of calls from the media and more than 10,000 leads and tips, hundreds of them from psychics. “Even some of the mainstream media have gotten into the tabloid kind of reporting,” he said, “but we are not letting the fury of the media destroy our credibility.”

More than 400 media professionals have signed up on a Web site sponsored by the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Department; it was created by a 20-year-old named Scott Campbell for $95, and it allows everyone to see the latest court documents, displays a photograph of a cell like Scott Peterson’s, and answers frequently asked questions about him. “I even get requests to interview the inmate who cuts his hair,” the sheriff’s spokesperson, Kelly Huston, told me. Sheriff Les Weidman said that TV people lurk outside the jail in hopes of catching a released inmate who might pass on a smidgen about Peterson. There are about 60 other inmates who have been awaiting trial on murder charges in the Stanislaus County jail, he added, some of them for as long as three years. “We have a guy who allegedly stabbed his wife and unborn child not that far away from Scott. He ended up on page 2 in the local-news section.”

To give some idea of the mass interest in the story, the official Laci Peterson Web site has received more than 20 million hits since January. “Every time we put [the story] on, the ratings spike,” Fox News’s Bill O’Reilly told me. “It’s the only thing keeping Larry King on the air. We do Laci Peterson every 15 minutes and see the numbers go up. It’s a story that resonates with women particularly.” Wendy Whitworth, executive producer of Larry King Live, countered, “I don’t determine what I do according to Fox.”

On Tuesday of the first week in June, for example, when the sharp-tongued former prosecutor Nancy Grace, who was acting as guest host on Larry King Live, discussed the latest developments in the Laci Peterson case, she had 33 percent more viewers—1.38 million households—than King himself had the next night with Dr. Bob Jones III of Bob Jones University. Greta Van Susteren, who has virtually turned her show into the Laci Peterson hour, is getting more than double the ratings of her main competitor, Aaron Brown on CNN, who specializes in hard news.

Granted, the audiences on cable are small—usually fewer than a million—but the Laci Peterson story is also a staple of network news in the morning and network magazine shows, which, combined with cable, represent a goodly part of the most fought-for time on the airwaves. Moreover, the depths to which those involved sometimes sink to get the story or to become part of the story have a pernicious influence across mainstream media. “It’s gotten out of hand, the reliance on the tabloids for stories,” said NBC’s Dan Abrams. “It’s just happened—it’s a new phenomenon.” (In the interest of full disclosure, I am married to Tim Russert of NBC News.)

Others point out, however, that NBC itself is trying to have it both ways. “Tom Brokaw can still be clean and pure on the network, and MSNBC can be as greasy as they want, and they can say, Hey, this is just cable,” said Tim Daly, a Stockton-based reporter for the ABC-TV affiliate in Sacramento, who is alarmed at the level of nonstop coverage of a single story. “We are not naïve enough to say that Laci Peterson is not news, but is it news every day? The answer is no.” Other local TV people in Modesto and outlying markets complained to me that unsubstantiated rumors about the case were too often making it onto the air. “I’ve done stories about all the false rumors just to dispel them,” Gloria Gomez, who is also based in Stockton, for KOVR, the CBS affiliate in Sacramento, and who got an early interview with Scott Peterson, told me. Yet her station broadcast as its lead story one night recently the unconfirmed account of a man who said that two years previously he had played golf with a man who might have been Scott Peterson, who told him he had gotten married too early and did not want children. That story was repeated to me by a local cabdriver—a potential member of the jury—as proof of Peterson’s guilt. One night, the panels of lawyers on Larry King and Greta Van Susteren made much of a potential witness on the shows named Michael Chiavetta, a neighbor of Scott and Laci’s who said he had seen the Petersons’ dog in a nearby park the morning of Laci’s disappearance, and perhaps even Laci herself in the background. I later learned that he has one glass eye.

In recent weeks, with so many defense leaks’ being endlessly speculated upon, the tide seems to have turned. A Fox News poll taken early in June showed that 58 percent of Americans thought Scott Peterson was involved in his wife’s murder. A month earlier the number had been 67 percent.

Having dinner one night in Modesto, I didn’t pay much attention to a blonde lady at the bar who was chatting and laughing with friends, but I did recognize one of the women with her as Kim Petersen, who is a very controversial figure in the story. Petersen is Modesto’s high priestess of grief management, the media handler for the Rocha family, including Sharon Rocha, Laci Peterson’s mother. Nobody gets near Rocha without Petersen’s O.K. So, in one of those surreal scenes that can materialize at any moment in a small town with a big story, I suddenly realized that the blonde woman a few feet away from me was Sharon Rocha, watching Greta Van Susteren interview two of Laci’s close friends over at the media bazaar. Rocha herself had been on the night before.

Stacey Boyers, one of the young women who had appeared on the show with her, who had known Laci since third grade and whose mother, Terri Western, had run the volunteer center that got the news of Laci’s disappearance out nationally in 24 hours, said she was forever being told by TV people, “Let us see you crying. Try to talk about the intimate moments, and when you start to lose it, don’t stop. Put your arm on your friend and hold on.” The traditional method of news programmers used to be to have people on the air who could advance a story, but that is no longer the rule. Now there are endless lengthy interviews that are virtually content-free. “Our mission is different,” Michael Reel, a producer with CBS News, told me. “It’s not being factual; it’s a different genre. We see people going through tragedy in the midst of the storm.”

Stacey Boyers and the Rocha family continue to be amazed at the callousness of some of the reporting they see on television. One night on Jay Leno’s show, Geraldo Rivera, referring to the continued dredging for the remains of Laci and Conner, said, “Every tuna in San Francisco Bay is going to be looking for lunch.” Rivera also took credit for announcing which limbs were missing from Laci’s body—information that had appeared in the Contra Costa Times newspaper a month earlier. Kim Petersen called a press conference to announce that Sharon Rocha had been shocked to hear without warning about the tape around the neck of baby Conner and the cut on his body. I asked Phil Griffin, head of prime-time programming at MSNBC, whether he thought the families in these situations shouldn’t get a heads-up. “If you did that, you’d spend all your time trying to reach people to tell them,” he said. “If you found out new information about Bill’s relationship with Monica, should you call up Hillary to let her know? I don’t think it’s our job.” Ironically, Sharon Rocha chose to tell of her anguish over what Dan Abrams of NBC first revealed about the condition of her grandson’s body to another NBC interviewer, Katie Couric, early in June.

Kim Petersen is a former third-grade teacher who learned grief counseling on the job as a volunteer in the 1999 Yosemite slayings and later became head of a foundation set up by the family of one of the victims, Carole Sund, to provide reward money to help find missing persons whose families cannot afford it. The Sund-Carrington Memorial Foundation counts among its board members Doug Ridenour, the Modesto Police Department spokesman, and Jim Brazelton, the Stanislaus County district attorney. Petersen has also worked with Chandra Levy’s parents, and on the walls of her office she has smiling pictures of her with a devastated Susan Levy in the company of Stone Phillips of NBC’s Dateline and other media celebrities. She frequently appears on Larry King Live and the Today show.

In the highly competitive atmosphere of Modesto, a gatekeeper such as Kim Petersen is always closely watched, and many reporters feel that she gives them short shrift in favor of more famous names. The Modesto Bee newspaper, which has been a model of probity on this story, makes a practice of rarely mentioning her name. Early last January, when Laci was still considered missing, Kirk McAllister, Scott Peterson’s original attorney, received a three-page anonymous letter signed by “select members of the local and national news media” condemning Petersen for “unprofessional bias towards select ‘favorite’ news organizations,” and for “inappropriately spreading rumors and innuendo about Scott Peterson.” (Petersen says the letter contained “blatant lies,” adding, “I wouldn’t ever care to do another media interview if my job didn’t require it.”) In June the Associated Press ran a story stating that much of Petersen’s energy and devotion went to the cases of well-off families such as the Rochas and the Levys “that don’t even meet one of [the foundation’s] basic criteria.” Kim Petersen’s response: “We help any family that needs our help.”

Whether she is liked by everyone or not, professional enough or not, Petersen has amassed her unique power base by keeping the media from suffocating shell-shocked families. She handles 95 percent of Laci’s family’s mail and instructs them on where to go for the largest audiences. She warns devastated families that they can expect to be questioned like suspects by the police. “I explain I want to reach as many people as possible in as few mediums as possible,” Petersen told me. “These families aren’t sleeping or eating. They age tremendously.” She said that people from all over the country call them in the middle of the night offering their thoughts and theories. “People take tragedy differently,” Petersen continued. “Some people need people around them.” Men, however, according to her, often say, “I want everyone to go home.” As for the media’s ethical violations, she feels they come with the territory. “When you get into a high-profile case, the dynamics and people’s motives are deplorable.”

Unlike O. J. Simpson, who never gave an interview before his arrest, Scott Peterson gave four, the first and most comprehensive to Diane Sawyer on ABC’s Good Morning America shortly after Amber Frey came forward, the others to local TV reporters Gloria Gomez, Ted Rowlands of Fox’s KTVU in Oakland, and Jodi Hernandez of NBC’s KNTV in San Jose. Peterson falsely claimed to Sawyer that he had told the police immediately about Amber Frey (he later called Sawyer and reversed that statement), and he also said that there had not been any other women in his life while he was married (there are already unconfirmed reports of two others).

Anything in those interviews that conflicts with what Peterson told police investigators will be fair game for the prosecution at his preliminary hearing, which is scheduled for later this summer. A number of reporters who had their phone calls to Scott Peterson wiretapped by the police are suing to have the contents released. I’ve learned that, after Laci’s disappearance, Peterson was a curious figure to those who saw him every day in Modesto before he left to spend most of his time in Southern California. “He was very controlling—he had his guard up,” said Ted Rowlands, who has broken a number of stories on the case. “He was very careful who he talked to, and he didn’t want the camera on him at all, probably because he didn’t want Amber Frey to see it—he had a couple of things going.” Others were struck by his lack of emotion. Gloria Gomez recalled, “I said, ‘You haven’t mentioned anything about the baby.’ ‘It’s very difficult’ is all he said.” Rita Cosby of Fox described Peterson as “numb and unemotional—more passionate about his golf game.”

Peterson could, however, apparently get quite animated at times, as he did about his desire to have a pet psychic flown in. “She claimed she could be with McKenzie [the Petersons’ dog] for a day and be able to tell us what happened,” said Terri Western, then director of the volunteer center. “He said, ‘Let’s bring her out.’ ” When the idea was vetoed, Scott said he would break the news to the psychic, adding, “I’m also letting you all know that if she’s had to pay for her flight, and it’s nonrefundable, I will be reimbursing her.” Since then, several of Laci’s friends who made a number of appearances on television in which they showed little support or enthusiasm for Scott have received identical letters from him. Terri Western, Stacey Boyers’s mother, paraphrased Stacey’s for me: “It’s hard for me sitting in this cell knowing it’s Laci’s birthday; we had a tradition that we would fly a kite on her birthday. So if you get a chance, I’d really like for you to go fly a kite.”

Mark Geragos continues to predict vehemently that the “real killers” will be found. “It’s clear she was abducted—that’s the only thing that makes sense,” he told me. “It’s only a matter of time forensically and we’ll find out who did it.” Geragos said that a number of women had been abducted by “some pretty sick people out there,” and that “we’ve got subpoenas out for records on various people.” When I asked him how he knew the brown van the police had picked up a second time to check out was the brown van—the one the defense had leaked about so extensively that the police had to examine it a second time—he said, “We don’t necessarily.” It will be tested again by the defense. Former judge Robert G. M. Keating, dean of the New York State Judicial Institute, told me, “Defense lawyers often try to throw out red herrings in hopes that some member of the jury someday will say, ‘Hey, what about that dragon somebody saw?’ ”

Geragos wants to move the trial out of Modesto, where polls indicate that an overwhelming number of people think Scott Peterson is guilty. Not surprisingly, Geragos says he “doesn’t mind” the media circus, but he admitted, “There is no way you can justify the coverage of this case.” His change-of-venue strategy would argue that the press overkill is merely confined to cable TV, so if potential jurors didn’t watch cable, didn’t live in Modesto, and weren’t exposed to courtroom cameras during the preliminary hearing, there could be a chance of impaneling an untainted jury. “In cable, to some degree, you see the Internet skipping over into the mainstream, because the Internet is so closely aligned to cable,” he told me. “Then the networks go to cable to see what they can come up with. It’s a circle jerk.”

I found it quite interesting to learn, a mere three days after my conversation with Geragos, that Judge Roger Beauchesne had written, in a ruling pertaining to unsealing affidavits leading to search warrants in the case, that the defense, in a private meeting with him, had not produced evidence indicating that it was investigating any other suspects. In response, Mark Geragos has asked the court to remove Beauchesne from the case.

If the reporters and newscasters covering the Laci Peterson case want to grade themselves, all they have to do is follow the preliminary hearing, set for later this summer, when the prosecution will finally present some of the actual evidence—the real facts. Then the world will be able to see just how much of the endless speculation that has gone on is valid. So far, from The National Enquirer’s discovery of Amber Frey to the various networks’ disclosures of the autopsy reports, the press has often been the engine driving the case. To take just one example, I would like to know the truth about a mop taken from the Peterson house. The National Enquirer stands by its story that blood and vomit were found on it. John Coté of The Modesto Bee told me only blood was found, and Gloria Gomez said the mop had nothing at all on it. “Half the stuff you hear you don’t report, because you can’t substantiate it,” Ted Rowlands told me. “I think a lot about what I’ve reported. Some of it will be true, some will be off. It will be really interesting to find out.”

In the interim, I have learned that the media’s frenzied scramble to keep the Laci Peterson case on the air shows no abatement. One day a reporter from a local channel asked if he could interview me as a member of the national media covering the case in Modesto. “You want to do a story on me doing a story on you?,” I asked incredulously. “Why?” “Because there is nothing else to report today!” a cameraman blurted out.

No Comments