Madonna and I are sitting side by side on her navy silk Deco sofa looking at Sex. The perfume of decaying gardenias permeates her steamy New York living room, a space that has, despite a Fernand Léger over the fireplace, the solitary feel of a deserted, if elegant,30s hotel lobby. Wearing ragged cutoffs and looking exhausted, her face blotchy and without makeup, she barely resembles the star auteur who flashes and slashes her way through the 128 pages of Sex, perhaps the dirtiest coffee-table book ever published.

Madonna and I are sitting side by side on her navy silk Deco sofa looking at Sex. The perfume of decaying gardenias permeates her steamy New York living room, a space that has, despite a Fernand Léger over the fireplace, the solitary feel of a deserted, if elegant,30s hotel lobby. Wearing ragged cutoffs and looking exhausted, her face blotchy and without makeup, she barely resembles the star auteur who flashes and slashes her way through the 128 pages of Sex, perhaps the dirtiest coffee-table book ever published.

I am not allowed to turn the pages. She turns them. As always, Madonna must be in control. “Pretend I’m not here,” the sex-for-sales matrix at the height of her power commands. Taking a break from 12-hour days in the recording studio, she is allowing me a first peek at what she hopes will be the worldwide publishing phenomenon of the year—her latest reinvention of her go-for-broke image: Pansexual Madonna, in your face hard, if not hard-core.

“She has a nipple ring? She pierced her nipple?” I ask weakly about a woman in one of the first images (some of the roughest trade comes right up front). “Everything in their body is pierced,” Madonna says of her two co-stars in the first section of Sex. The book is billed as the enactment of Madonna’s private sexual fantasies, brought to the page by her longtime collaborator, photographer Steven Meisel. Just to get things rolling, her first supporting actors are two unnamed, tattooed, and bare-breasted lesbian skinheads, who answered a casting call for the book, and whose appearance would probably cause Don King’s hair to go straight up to heaven.

“She’s showing me her clit ring. That’s why I have that expression on my face,” Madonna says. Her egad-I’m-caught look in another pose, she assures me, “is supposed to establish the humor of the book.” Nobody is smiling, however, in the many bondage images of Madonna—her fondling and sucking threesomes with the two women, complete with props that include masks, knives, and whips. “This is pretty scary,” I say of a photo of one of the skinheads holding an unsheathed stiletto right under the crotch of Madonna’s black bodysuit. “It’s mean to be funny, not scary,” Madonna says curtly. I other words, it’s your fault, dear reader, if you can’t get it as fun.

Of course, we all know that the 34-year-old Ms. Ciccone has never been one for a gradual buildup to shock. She seems to have a deep and complete understanding of its value. “She is someone who has a highly charged sexuality, and, unlike most people, she neither disguises it nor is ashamed of it,” says Nicholas Callaway of Callaway Editions Inc., the quality publishing house which is producing Sex for Warner Books. “She exhibits, explores, and displays it, and feels no compunction about doing so publicly. She also realizes it can be very profitable.”

In this latest mutation of the onetime pudgy boy-toy turned toned and hardened material girl, she is obviously twisted right from the git-go. In Sex, mainline heterosexual images are in short supply (the few there are mostly feature Madonna with rap artist Vanilla Ice, who, she says, reminds her of Elvis). The darker side of the sexual psyche seems much more in evidence—what Callaway calls “that grand tradition in sexuality, the relationship of love to aggression and violence.” He adds, “It’s a real high-low book, ranging from high to low constantly in content, form, and material. It’s a microcosm of what her career has been, a series of changing roles.”

Sex was shot in various locations, but mainly in New York—in a downtown sex club called the Vault, in the Chelsea Hotel, in Meisel’s studio, and at the Gaiety, a male burlesque theater. The word went out that Madonna was looking for people. “I said, ‘I’m doing a book on erotica, like my erotic fantasies,’ ” says Madonna. “I wasn’t too specific.” In fact, according to Callaway, “sometimes she brought people in, and within minutes of first meeting her they found themselves without their clothes on, French-kissing Madonna.”

Madonna’s persona in the book is Dita Parlo, a name taken from an old French movie Madonna became enamored of. Dita is known as “the good-time girl,” and nowhere is that more in evidence than in the photos shot in Miami Beach, where Madonna staged “public nudity” scenes, playing “the housewife left alone too much.” On any given day in Miami, Madonna would ride around in a convertible until the right locale resented itself. She would pull up to a gas station, hop out in nothing but black lace leggings, and start pumping gas. Meisel would immediately start taking pictures while art director Fabien Baron shot super-8 film for a future video. One night Madonna, wearing only a fur coat, ordered a slice of pizza, and when it was served, she threw off her coat and began to eat. “Customers really didn’t seem to mind I was naked,” Madonna says, “but the woman who owned the pizza parlor turned on an alarm to summon the police, so we kind of got out of there pretty fast.”

Madonna’s major fantasy of being nude in public places was fulfilled when she started hitchhiking one afternoon in nothing but a pair of spiky black pumps and carrying a purse. Nobody recognized her. “A lot of cars just passed me by, believe it or not.” One cyclist, however, got right up close and “fell off his bike.”

The resulting photo album of the star who flaunts what others choose to hide is certainly unprecedented. But let us not neglect the debut of the writer here. Madonna’s whimsical aphorisms, such as “My pussy has nine lives,” and essayettes on the splendors of sex with other women are also part of the package, included, it would seem, to counteract the harshness of some of the images. In one lighthearted poem she says, “Her body was a weapon, not a fatal weapon / More like a stun gun / More like a fun gun / She did it to remind everybody she could bring happiness or she could bring danger / Kind of like the Lone Ranger.” There are also a series of “Dear Johnny” letters, which depict Johnny, a fictitious character, and Madonna sharing a girl called Ingrid, “a friend,” Madonna says, in real life.

Here a few sample passages from the playgirl’s philosophy—and hardly the raunchiest. On being tied up: “Like when you were a baby your mother strapped you to the car seat. You wanted to be safe—it’s an act of love.” On sadomasochism: “You let someone hurt you who you know would never hurt you. It’s a mutual choice.… I don’t even think S and M is about sex. I think it’s about power.” On enjoying being a woman: “I love my pussy. I think it’s complete summation of my life.” Continuing the same theme: “I wouldn’t want a penis. It would be like having a third leg. It would seem like a contraption that would get in the way. I think I have a dick in my brain. I don’t need to have one between my legs.”

As we went through the pages—of Isabella Rossellini dressed like Mick Jagger in Performance hugging Madonna, of Madonna nude between black rapper Big Daddy Kane and black supermodel Naomi Campbell, also nude, and of Madonna shaving the pubic hair of a leather-clad male biker with a straight razor—I thought it not inappropriate to ask the just-how-did-you-ever-get-the-guts? question, followed closely by the and-just-how-do-you-justify-this-love-of-the-polymorphous-perverse? query.

“I don’t have the same hang-ups that other people do, and that’s the point I’m trying to make with this book,” Madonna says, scrunching up waiflike in a corner of the sofa. “I don’t think that sex is bad. I don’t think that nudity is bad. I don’t think that being in touch with your sexuality and being able to talk about it and being able to talk about this person and their sexuality [is bad]. I think the problem is that everybody’s so uptight about it that they make it into something bad when it isn’t, and if people could talk about it freely, we would have people practicing more safe sex, we wouldn’t have people sexually abusing each other, because they wouldn’t be so uptight to say what they really want, what they really feel.”

Nevertheless, legions of parents of Madonna fans will probably be outraged and consider Sex crude and salacious. Do you really want your idol thinking these things? Knowing these things? Doing these things? Feminists will blanch at her cavalier attitude toward issues such as spouse abuse, and many others will undoubtedly see the book as nothing more than a risky, if not downright desperate, bid to stay in the public’s mind, no matter what the consequences. “This is high-stakes on every level,” says Callaway, “in publishing terms, in ethical terms, financially, artistically.”

Madonna’s celebrity is unique in that it seems to depend as much on repugnance as on acceptance. Her fame frame, unlike that of most other mega-stars, rests very much on people who love to hate her—while monitoring her every move—and on others who hate to love her, as well as on the traditional adoring fans. Perhaps it’s not surprising that even academics are doing a brisk trade in Madonna-ology. This fall the pop star’s major competition in the book world is a collection of essays entitled The Madonna Connection: Representational Politics, Subcultural Identities, and Cultural Theory (Westview Press).

She’ll take it all. Anything, it seems, even derision, in order just not to fade away. Certainly there is no shame, and there never has been. In 1984, Madonna’s fame exploded with “Like a Virgin”; at the same time, a negative cover story appeared in Rolling Stone, recalls Liz Rosenberg, her longtime publicist and close friend. “We found out then it was because people both hated and loved her. Suddenly everyone had to take a stance on Madonna.” Rosenberg quickly adds, “I love when people really hate Madonna—Madonna does, too. She’d rather that than apathy.”

These days, however, with Sex on the horizon, the affable Rosenberg is holding her breath. “I’ve been at this point in Madonna’s career before,” she says with a sigh. Rosenberg, who is head of publicity for Warner Bros. Records, has already gone through at least a half-dozen other controversies over Madonna, involving vulgarity, blasphemy, and sexual explicitness, from “Like a Prayer” to “Justify My Love” to Truth or Dare. They seem to come along every year or so. Still, Rosenberg seems shaken by what she has seen in Sex. “There’s a lot to hate in that book,” she admits. She also worries for Madonna’s security. “Psychos might see there’s a message in it for them.”

Surely, Sex is a middle finger raised to those who preach “family values.” It is also bound to drag its publisher’s parent, Time Warner—already under fire for first defending the “cop-killing” lyrics of rapper Ice-T and then, at his request, removing the offensive single from the album—once more into the sort of controversy that stockholders abhor. The book has a sleek high-tech, Pop-art design—spiral binding and metal covers—and it is meant to be thought of as “almost like a sex toy,” according to Fabien Baron. It also contains a CD of Madonna’s soon-to-be-released single, “Erotic,” with lyrics that fit the themes in the book. From Madonna’s so-far-unerring point of view, Sex is her hedge against getting stale, her latest ploy to stay the leader of the pack, to be downtown and artsy—more Andy than Marilyn. It’s a product designed to melt whatever plastic still clings to her too callow or too pop musical image, and a way to counterprogram the defunct—for her—notion of overexposure.

“She has to reinvent herself every time out, and if she misses the wave, she’s history,” says prominent music-business attorney John Eastman, who does not represent Madonna but handles such stars as Paul McCartney and Billy Joel. “She’s a phenomenon rather than a deep creator.” So, like, just when you thought Madonna might be stuck catching pop flies in her cap and sliding into second with her tender No. 1 summer hit, “This Used to Be My Playground,” from A League of Their Own, wailing in the background—pow! We are introduced to the Naked Marketeer.

Consider her global plan. Sex will be the biggest international launch of a book ever: on October 21, 750,000 copies go on sale simultaneously in Japan, Great Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, in all the various languages. The book retails for $50 a copy, so the profit on the first printing alone could run to $20 million. More than two million copies of her album Erotica will be released at the same time. Together, she says, they are the work she’s most proud of to date. The videos will not be far behind. Naturally, hype has dictated that Sex be a work conceived in tightest secrecy; it has already survived a theft broken up by an F.B.I. sting, and it is hitting the bookstores in a vacuum-packed Mylar bag that has to be cut open. To keep the heavy breathing hot, Madonna wants no copies of the book displayed outside the Mylar bag, and the package carries a label warning that Sex is for adults. She is arrogant enough to want consumers to buy her sight unseen, so to speak.

Then, in late January, Madonna will perform simulated sex and masturbation on 2,000 screens across the country in Uli Edel’s courtroom drama, Body of Evidence, for which she was paid $2.25 million, a modest sum considering her celebrity but not in light of her track record onscreen (eight movies and only three commercial successes—Desperately Seeking Susan, Dick Tracy, and A League of Their Own, in which she has a minor role). Body of Evidence, which co-stars veteran actors Willem Dafoe, Joe Mantegna, and Anne Archer, is the less-than-heartwarming story of a psychotic sex fiend who is accused of murdering the rich old man she’s involved with by screwing him to death. A studio executive says it’s about “hard sex—there’s no loving here.” Madonna made even big Hollywood players gasp when the dailies were shown. “All of us were really shocked watching these sex scenes. You never quite expect to see this behavior in a star.” The executive can only offer by way of explanation, “She has not conquered movies yet; it’s an obsession with her.” But what is she really up to? In the view of one Hollywood observer, “She’s out to desensitize us and demystify sex.”

“They’re going to edit a good performance out of her,” says someone who was on the set of Body of Evidence. Madonna says she found simulating sex on-camera more difficult than she had imagined. “It’s hard enough to bare your soul in front of the camera. But it’s even harder, I think, to be baring your ass at the same time.” Immediately following the movie’s U.S. premiere, Madonna, a frequent insomniac who seems almost pathologically driven, will personally promote it internationally. Does she ever slow down? Not really. “After two weeks of being naked simulating sex with Willem Dafoe on the hood of a car,” she says, “I just want to go home for a week and not take my clothes off.”

Freddy DeMann, Madonna’s manager, speaks very quietly and pads around in soft velvet slippers. It is the sound of money talking. Together, he and Madonna are planning to build an entertainment colossus—“I already have an empire,” says Madonna—and you wouldn’t necessarily bet against them. A self-described “Brooklyn Jewboy,” the tanned, 53-year-old Freddy DeMann, who once managed Michael Jackson, is one of a small, tight knot of people who have been with Madonna since the beginning, which was almost a decade ago.

When the breadth of Madonna’s amazing worldwide celebrity is measured, people such as DeMann, who early recognized the power of MTV and videos, as opposed to radio airplay, to sell Madonna’s image, and Liz Rosenberg, who taught her to cultivate the press, not hide from it, and Seymour Stein, the godfather of New Wave music and the head of her longtime record label, Sire Records, have to be included prominently on the yardstick.

DeMann in Los Angeles and Rosenberg in New York are “the grown-ups,” the surrogate parents, who freely admit they devote more time to Madonna than to their own families. “My husband has to compete for my time with Madonna,” Rosenberg says. “At the very moment my husband proposed to me, I said, ‘Yes, I’ll marry you, but I have to go on Madonna’s tour.’ ” “She has a way of demanding that compels you to give her your undivided attention,” says DeMann.

Even today, the normally taciturn DeMann can sit in a massive suite at the St. Regis hotel in New York and go ballistic with adjectives when recalling his first meeting with the sexy little urchin from Pontiac, Michigan, the product of a strict Catholic household, whose mother had died when she was six. “She had the most unbelievable physicality I’ve ever seen in any human,” DeMann says. “She was enrapturing, she was just captivating, she had the same moxie she has today. She was just unique, wearing her rags and her safety pins.”

Liz Rosenberg was similarly seduced and captivated. “Before I met her, I had a premonition I’d meet an artist who’d play a big part in my life, that I’d be very devoted to.” Then Madonna walked in, in rags again, with 100 rubber bracelets up her arm. “I loved her energy. She was an original. I was a big believer.” But Rosenberg’s polished pitch letters aside, back then no self-respecting pop-music writer was about to give space to a little one-hit dance diva.

Rosenberg finally got a reporter from Newsday to interview Madonna, and at that first interview the great manipulator gave all her answers looking at Rosenberg. Today, it’s amazing to think that Madonna ever needed a second’s coaching about the media. “I had to tell her to look at the writer instead of me.” How about today? “She’s brilliant and frustrating and part of the fabric of my life at this point. I have to tell her to eat—I’m like her Jewish mother.” Rosenberg even admits, “I dream about her constantly.” But the one thing Liz Rosenberg won’t do for Madonna is leave Warner Bros., where she supervises the publicity for 100 other recording artists, to go to Maverick, Madonna’s new, multimedia, multimillion-dollar company.

Last April, after a solid year of negotiations overseen by Freddy DeMann and orchestrated by attorney Allen Grubman, Time Warner announced a joint venture with Madonna that gave her her own record label, also named Maverick, and a two-book deal with Warner Books (Sex is the first), as well as a music-publishing company, plans for HBO specials, and TV and film divisions. The deal is so complex and operates on so many levels that DeMann says putting zeros after its worth is just pure speculation, since all figures—such as the $60 million that has been thrown around in the press—will be based upon how its eventual products perform. Certainly, Maverick is being given more than sufficient start-up money by Time Warner, which it must recoup in a few years or, Madonna says, she must pay back out of her record royalties.

“Warner’s didn’t hand me this money so I could go off and go shopping at Bergdorf’s. I have to work, I have to come up with the goods,” Madonna says. “The deal with Warner’s isn’t necessarily about me. It’s about developing other talent. There’s tons of talent out there, and the idea of finding it and nurturing it and shaping it and giving it life is very exciting to me.” To that end Maverick has recently signed its first act, Proper Grounds, five L.A.-based black “anguished rock rappers,” according to DeMann, who was busy all summer hiring executives to head Maverick’s various divisions. Naturally, Madonna is keeping close tabs on everything. “There’s the bands I have to go see and the tapes I have to listen to, and there’s the publishing deals I have to approve of, and there’s the employees that I have to hire to run the company and the interviews that have to take place and the scripts I have to read for movies that I would like to act in. And there’s the books I’d like to read that I would consider buying to make movies out of as a producer, and the list is endless.”

There is no question that Madonna wants to be a movie star, but so far she has been scorched by the critics, and she’s hampered, she says, by having to find parts that her strong offscreen personality won’t overwhelm. She currently has a script in the works on the life of dance pioneer Martha Graham to star in. Dino De Laurentiis, who produced Body of Evidence, wants her to play Marilyn Monroe in The Immortals, Michael Korda’s fictionalized, if exploitive, version of the last days of Monroe and her relationship with the Kennedy brothers. But Madonna feels that trying to play Monroe, from whom she has borrowed so much, is “probably a stupid idea.”

A manuscript of The Immortals is on a shelf right above her desk, directly under a beautiful Picasso portrait of a woman in a blue hat. Madonna now has her own art curator to advise her on what to acquire. Rosenberg says, “What does Madonna want to do when she grows up? She wants to be Peggy Guggenheim.” But there is so much else to do first.

“I don’t believe Madonna’s taken a full week off in nine years,” says DeMann, and that was surely part of the investment return Time Warner figured on when granting the Maverick deal. “She’s willing to defer a relationship, throw having children aside—perhaps forever—in the elusive search to be a celebrity,” says a high-ranking Time Warner executive who knows Madonna. “She’s willing to defer everything for this. For more covers of magazines. More just feeds on itself. It’s like an addiction. Sometimes, in business, you like people to give up everything, to be wholly involved in their projects.”

Neither DeMann nor Rosenberg pretends that Madonna is happy. Even De Laurentiis, who is dying “to discover her” the same way he did “Schwarzenegger and Jessica Lange, justa to name two of the latest,” says, “She’s a very lonely woman. She needs love and affection froma the people.” “I encourage her to sit back, reflect, enjoy the success, but it’s really tough for her,” says Rosenberg, adding, “She’s not good at that.” “I don’t know to what extent she enjoys life,” says DeMann. What he is certain of, however, is their mutual unsatisfied yearning. “I think we seem to fulfill a need in each other. Her need to do and be—I have the same need. We have a need for approval and accomplishment, and we’ve accomplished a lot. But we’re both hungry. We have to prove ourselves over and over to ourselves and to others. Why? We’re crazy. We both recognize that pattern.” His black velvet slippers sink into the carpet. “Nothing will ever be enough,” Freddy DeMann declares. “Never.”

I ask DeMann if he is expecting shock waves over Sex. “A lot of people will obviously object to the book,” he says. “Warner Books is shitting in their pants about it.”

Later, I ask William Sarnoff, chairman of Warner Books, if he thinks he’ll get away with this.

“What do you mean?” he asks.

“Clearly, this book has a lot of material that many people will find extremely shocking. Now, in light of the hullabaloo you’ve just gone through with Ice-T and his lyrics, do you anticipate you’ll have the same reaction from some people, and do you think you can get away with it?”

“That’s a very good question, and I will be happy to respond to it.” When I press him, he says, “Not now.”

Five hours later, Sarnoff phones this response: “We’re not trying to get away with anything. This is a book Madonna is doing about her erotic fantasies. As publishers, we will publish it in a Mylar bag to avoid browsing, and there will be a warning on it. It will be a unique book, and I think it may redefine the illustrated book. As far as Madonna is concerned, she should pursue all avenues of creativity as she defines it. And we will do as much as we can to bring it to the proper audience.”

‘So what are you going to do when you get older, Madonna? Time Warner waits for no woman. Are you going to be going on 50 and still get up onstage and shake your booty, like Cher? What happens when your body goes?”

“Then I’ll use my mind.”

On location for A League of Their Own in Indiana, Madonna chafed at the length of the shoot and used her time off the set to write. By the time she left the film, she had firmed up the original concept for Sex. Then she sat down with Meisel.

“We had meeting after meeting,” says Madonna. “What kinds of places do you want to go to? You want seedy hotels? Nice hotels? Outside on the street? Inside of a car? We had to run the gamut of, like, what’s erotic?” Meisel quickly found out. “She considers homosexuals erotic. She liked two men together, two women together. It turns her on,” says Meisel, who believes “we’ve covered it. We’ve gone as far as we can in public.” But even he seems wary. “I don’t think anyone else needs to do another photo essay on erotica—this is it. Basta!”

Throughout the process, Madonna was the hawk-eyed producer, hiring French-born Fabien Baron, currently the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, to design the book, and later bringing on as her editor writer Glenn O’Brien, whom she knew from his days as an editor at Interview. Madonna herself went over all 20,000 frames that were shot. It took her four weeks. “Ninety percent of the time her eye was right on the button,” says Baron, who adds, “America is too Puritan. Sometimes you have to slap people in the face to have them change.”

“We just wanted it to start off with a bang,” says O’Brien. “We thought it would be nice to start off shocking and wind up with a sense of humor.” While Madonna was on the set of Body of Evidence, O’Brien would send her assignments to write, which were to clarify her feelings. “Everyone’s different,” Madonna says of the book’s content. “The most important thing is to be tolerant of that, to accept it, not to be scared of it or threatened by it. There’s enough shocking in it that people can see things that would make people feel uneasy, [but they] could try to see it another way.”

“So you’re out to shock people?”

“No. I’m out to open their minds and get them to see sexuality in another way. Their own and others’.”

Meanwhile, Baron was beside himself with his demanding, hands-on manager on the phone to him every day. “One hundred twenty-eight pages, same subject, same person, and each page she’s nude! It’s hard. What do you do with it?” He was determined that form would lead content. Baron didn’t want anything that would look like a normal book. The metal covers, he declares, are “aggressive,” followed by cardboard inside, which is “warm. It’s like layered.” As you open up the candy-bar wrapper, you can think of it as “unwrapping a sex toy,” Baron says. He licks his lips. “Schlurp! The excitement isn’t just her. Everything should be to the level of who she is.” He advises, “Put on the CD and look at the book. It could almost be a video in a way.”

Enter Nicholas Callaway, who has produced two elegant coffee-table books on Georgia O’Keeffe, as well as last year’s admired volume of Irving Penn’s photographs. It was his job to mass-produce 750,000 copies of a complicated, handmade-looking art book printed in five colors and five languages with several different kinds of paper and an eight-page comic strip, the kind of book, he says, that ordinarily you “might expect to see only 250 copies made.” For the covers, he tells me, “we ordered three-quarters of a million pounds of aluminum. You can stamp a number on each one.” The packaging required heat-sealing. As to opening the Mylar bag to get to the book, Callaway says, “We wanted there to be an act of entering, of breaking and entering.” It took a MacArthur Fellow, the printing and publishing wizard Richard Benson, to figure out how to produce the quality they were after on a three-story-high, ultra-speed press that would churn out 25,000 impressions an hour instead of the usual 5,000 for such books. So instead of taking six months to print, the whole book is being produced in a record 15 days.

But technology was only part of the equation. Several printers who could produce the volume required simply refused to have anything to do with the lucrative contract on moral grounds. The midwestern printing firm that finally accepted the job will not allow its name to be used, and gave its employees the option of shifting crews and not working on the book at all if they objected for ethical, religious, or moral reasons. Nevertheless, Callaway thinks he’s witnessing not only the latter-day version of the release of Lady Chatterley’s Lover but also a daring and bold act of self-made iconography. “To preserve oneself for history at the peak of one’s form—your body does not remain the same. What other figure in the history of entertainment has done this? It really is a radical act.”

The F.B.I. man in Los Angeles had spent one whole day last June being coached on how to talk like an oily tabloid editor. Now it was night at the Sunset Marquis Hotel, and he and a reporter from the British tabloid News of the World, as well as Gavin de Becker, Hollywood’s leading safety and privacy consultant, who is employed by Madonna and many other stars, were waiting for the man with the stolen pictures.

Sex had been shot under the strictest security. Anybody remotely involved in the book was obliged to sign a statement of confidentiality and forbidden even to speak of its contents. Fabien Baron himself had installed a special alarm in his studio, where he hid the book layouts in a closet every night. But late last May, de Becker—who never publicly speaks of client matters, but has been authorized by Madonna to speak about this case to Vanity Fair—heard from a source in “the tabloid community” that someone in New York was trying to sell a batch of explicit pictures from the book. The person had contacted News of the World. Asking price: $100,000 minimum.

“We negotiated a deal with News of the World,” says de Becker, who made it clear that if the paper tried to publish the pictures it would sue immediately. One of Madonna’s legion of lawyers faxed the same message to 17 other publications around the world. News of the World agreed to set up a meeting with the contact in Los Angeles in exchange for being allowed to print a story about the incident, and the U.S. attorney in Los Angeles agreed to participate in a sting. “If we could arrange to get the guy in the right place,” said de Becker, “they would nab him.”

After being sent an airline ticket, a 44-year-old New York man named William Stacey Anderson flew to Los Angeles. De Becker had an agent on the plane and others at the airports, but nobody knew what Anderson looked like. Fortunately, he contacted the News of the World reporter in the reporter’s hotel room—which was wired so that their conversation could be recorded—and duly showed up with 44 perfect prints in a box. De Becker, who was monitoring the conversation, said Anderson balked when he saw the F.B.I. agent, who was posing as an editor—his meeting was to have been with the reporter only—but he calmed right down when the agent showed him $50,000 in cash and said he had to go get the rest of the money.

When the G-man returned to the room, he flashed his badge and took Anderson into custody. Ironically, the alleged culprit was a woman who worked at the New York photo lab that was processing the pictures. She is still at large. “I wanted them to arrest the girl,” Madonna says. “But now they can’t find her, and the F.B.I. is, like, on to the next case.”

Naturally, such a drama brought down paranoia and suspicion among the 50 or so people connected with the book until the mystery was solved. “All this security made everything a lot slower,” says Barron. Paranoia struck several more times in the following weeks, once in London and once in New York, where Bob Guccione and Penthouse got into the act. A couple claimed to have found more of the same pictures on a bench in Central Park. Guccione, who Madonna says would have liked to serialize the book in Penthouse, agreed to help out, and had his staff set up a meeting. When the couple walked into Guccione’s office, they were met by a detective from the New York City Police Department. But the couple had a foolproof story: they claimed they had had no idea how to return the pix, so they had thought it best to hand them over to Mr. Guccione. “Please get them to the right people,” they said.

After a decade of perhaps the most glaring media exposure in history, Madonna still feels that she’s misunderstood and that she isn’t taken seriously enough as an artist. “I think I’ve been terribly misunderstood because sex is the subject matter I so often deal with—people automatically dismiss a lot of what I do as something not important, not viable or something to be respected.” By the same token, Madonna resents being singled out for being such a brilliant marketer of her own image. “I think people like to concentrate on that aspect of me so they don’t have to pay me any respect in the other categories. They never say, ‘Oh, she’s a beautiful songwriter,’ or ‘That’s a nice photograph,’ or ‘That was good acting,’ or ‘That was a great performance onstage.’ Everyone always says the same thing: ‘She really knows how to market herself.’ And to me it’s an insult in the form of a compliment. I don’t think that is why I’m successful. It’s also what I’m marketing and what I am saying.”

These days Madonna, who believes those who disagree with her are either “not in touch with their sexuality or threatened by me being in touch with mine,” is talking like a soul sister of Dr. Ruth, only the packaging is a little different: “I am not going around saying everyone should fuck more,” Madonna says. “That is not the point. The point is just to feel comfortable with yourself and whatever you want to do. Whether it’s be with another man. Be with another woman. Be with three people. Be alone. Masturbate. Whatever. You shouldn’t feel shame about it. It’s not quantity, it’s quality. And honesty.”

It is a hot Sunday afternoon. Madonna is violating her rule of not working weekends to do this interview. But work is work is work. She is in a long navy column of a dress, her white bra and bikini underpants showing through, and she is wearing high-heeled open-toed sandals and little makeup or jewelry. She is surprisingly small in person and not an overwhelming physical presence. The electricity is conserved for the camera or the stage.

“Do you enjoy sex?” I ask her.

“That’s like saying to a gynecologist, ‘Do you enjoy having children?’ Why? Because you deliver babies all day, you can’t enjoy having your own child? There are so many different levels of sexuality—I absolutely do enjoy it. I think I should just shut up and go away about all of this if I don’t enjoy sex.”

But she is alone in her apartment overlooking Central Park West, and she gives the impression of being quite alone, although there are always reports of girlfriends and bodyguard boyfriends floating around. (The most recent names in the gossip columns are those of Jimmy Albright, a handsome fellow in his mid-20s who works in security, and ex-model–nightclub owner John Enos.) Her hair is wet on the ends, scraggly, and her part is wide and dark. As usual, she has been pushing herself hard, and in fatigue she tilts on that thin edge where street chic can all of a sudden look trashy. On the other side of a glass-topped coffee table covered with art books, she sits rigidly as we speak, and rarely if ever smiles, but her compelling eyes often spark. There is an icy coolness about her that cuts right through the heat. This is strictly business—all business.

“Sex is not love. Love is not sex,” Madonna proclaims. “But when they come together, it’s the most incredible thing.”

“What do you think the proportion is of their coming together?”

“For me? A lot. I would say I probably very rarely in my life had sex with someone that I didn’t have real feelings of love for. Because ultimately I can only allow myself to be really intimate with someone if I really care for them.”

She is quick to respond, smart, and confident of her ability to answer. When a question bothers her, she inadvertently bites the knuckles of her hands, almost as if she were trying to jam her fist into her mouth. And if she is truly holding something back, the black elastic that’s meant to keep her hair in place gets twisted around and around her fingers. For example, the new album reportedly contains one song which some people think is Madonna’s ode to love with other women. Indirectly, she seems to acknowledge, while twisting the elastic, that she has tried sex both ways.

“Which do you prefer?”

“Which kind of sex do I prefer? Hetero sex.”

“But you also like the other kind as well?”

“It’s not, Do I like the other kind as well? I have a lot of sexual fantasies about women, and I enjoy being with women, but by and large I’m mostly fulfilled by being with a man.”

“But you can also be fulfilled by being with a woman sometimes?”

“It’s not the same.”

The one subject on which Madonna actually appears vulnerable is that of having children. She says the sight of beautiful children while she’s running in the park fills her with longing. It doesn’t help that with both her ex-husband, Sean Penn, with whom she was seen holding hands on the set of Body of Evidence, and her most famous recent ex-lover, Warren Beatty, have both become fathers lately. “I think it’s amusing that every time I break up with somebody they get married and have a baby with somebody,” Madonna says as she begins curling the hair elastic again. She speculates, “Maybe they feel emasculated by me.” She grabs one hand with the other in an effort to stop the twisting. “Sean wanted to have a child. And we talked about it all the time—Warren and I. Um, it just wasn’t the right time. For them either. You know, everything is about timing.”

Madonna calms her hands. “I think about having children all the time. There is a part of me that says, Oh God, I wish that I was madly in love with someone and it was something viable, something I could really think about. But I don’t idealize childbirth, and I don’t want to just go get knocked up by somebody,” she adds. “I think it’s important to have a father around, so when you think about that, you have to think, Is this person the right person?”

Suddenly the tiny part of Madonna that clings to being the good little Catholic girl she was brought up to be comes forward and she sounds as if she’s siding with Dan Quayle. “I think that there is merit in praising family values, and I think that in this day and age there’s a lot of fatherless children, and I think that if children had fathers as role models—um, I don’t know—I think it’s important to have a father, O.K.? And a mother. On the other hand, to condemn someone [such as Murphy Brown] for making that choice is irresponsible.”

As the oldest daughter in a family of eight children, including two half-siblings who were born after her mother died and her father remarried, the rebellious little girl who was constantly called upon to help care for the younger kids is strictly pragmatic about maternity. “I don’t have any romantic notions about having a baby,” Madonna says, referring to her childhood. “You were very clear that it was about cleaning dirty diapers and baby-sitting and not having time to hang out with your friends and listen to babies scream all the time and cleaning up their vomit on your shirt. It’s a really tough job.”

Madonna, who’s in therapy, can see that her obsessive drive and perfectionism are a need to control what she could not control in early childhood, and what subsequently caused such pain. She also admits that her need to dominate stems from “losing my mother and then being very attached to my father and then losing my father to my stepmother and going through my childhood thinking the things that I loved and was sure about were being pulled away.” The fact that, even today, her engineer father refuses to acknowledge her celebrity on visits home must make her desire to shock and succeed all the more powerful.

“I didn’t have a mother, like maybe a female role model, and I was left on my own a lot, and I think that probably gave me courage to do things,” she explains. “I think when you go through something really traumatic in your childhood you choose one of two things—you either overcompensate and pull yourself up and make yourself stand tall, and become a real attention getter, or you become terribly introverted and you have real personality problems.

“The courage part comes from the same place the need for control comes from, which is, I will never be hurt again, I will be in charge of my life, in charge of my destiny. I will make things work. I will not feel this pain in my heart.”

Around men, Madonna is completely different, more relaxed and flirtatious, full of Goldie Hawn–ish giggles: terra firma. At the Hit Factory, the recording studio on the West Side of New York where she is finishing her album, she is wearing a dozen different trends at once: a distressed flannel shirt with the sleeves ripped out, to which she has pinned a not button but which she has unbuttoned to let her black bra show and then knotted under her midriff; extremely distressed cutoff jeans that hang low and allow her black Calvin Klein underpants with the white elastic waistband to peek through; heavy white athletic socks and clumpy black high-laced Doc Martens, of the sort favored by Israeli paratroopers and downtown bohemians. Her hair is uncombed, and she is chewing bubble gum. But there is no question at all who is the boss.

The New York Times has just been had with a story about Madonna. It swallowed whole a fabrication about her having a limousine pull up in front of an upscale ice-cream parlor and demanding take-out chili dogs for lunch. Liz Rosenberg has called the Times but isn’t bothering to demand a retraction—not with what she has to contend with around the world regarding Madonna. “Chili dogs–how gross,” says Madonna. “I’m a vegetarian.”

Since she is so adept at managing her celebrity, I ask her, during breaks while she mixes the backbeat of one of her new compositions, whether anyone else taught her about it—you know, like Warren Beatty maybe. She looks slightly incredulous. Warren? “I learned a lot from Warren, but it wasn’t about how to handle the press and deal with celebrity. I think he learned about that from me. And he even tells me that.” “Right—look how he had that baby right before the Academy Awards,” adds Liz Rosenberg. “He was staying away from the press at all costs, and now he has gone completely in the other direction.”

Madonna pops a big bubble before being asked to listen to a few bars of what they’re trying to mix. She nixes it. “Joey, I think you’re going to have to move the boom.… I think you’re not going to make it.… Shep, it’s not working,” she says to her producer, Shep Pettibone. “I believe Shep is a genius, but we’re not having it.” “I like it,” the engineer protests. “I don’t care,” Madonna answers. “Put it on your record.” She lowers the boom with soft little laugh. “Shep, it’s cheesy. I don’t want it.” A final pop of the gum from Madonna closes the case. “I’m sorry, this is not a democracy.”

Original Publication: Vanity Fair, October 1992.

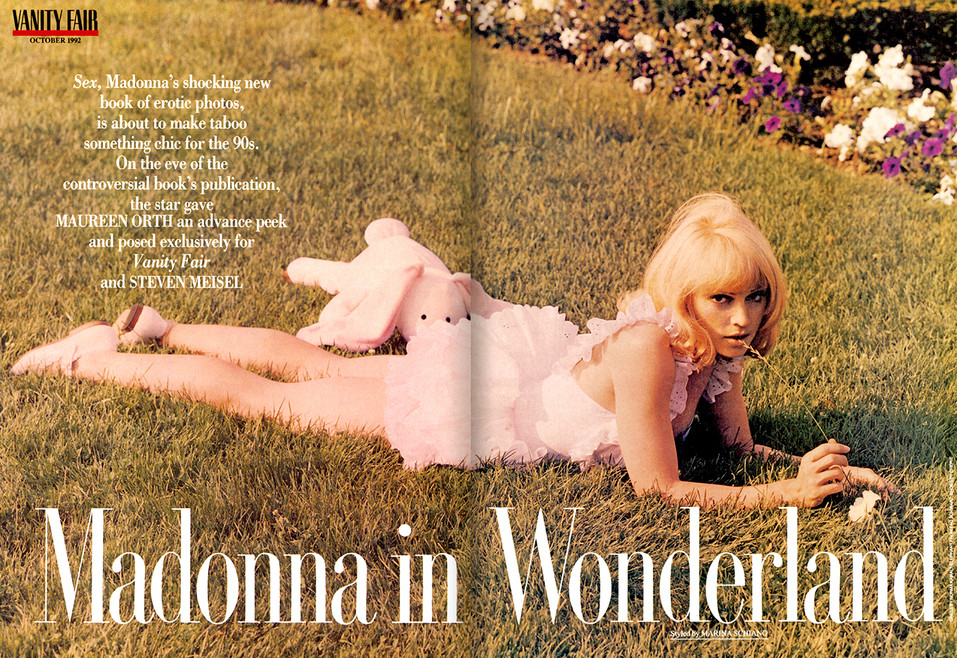

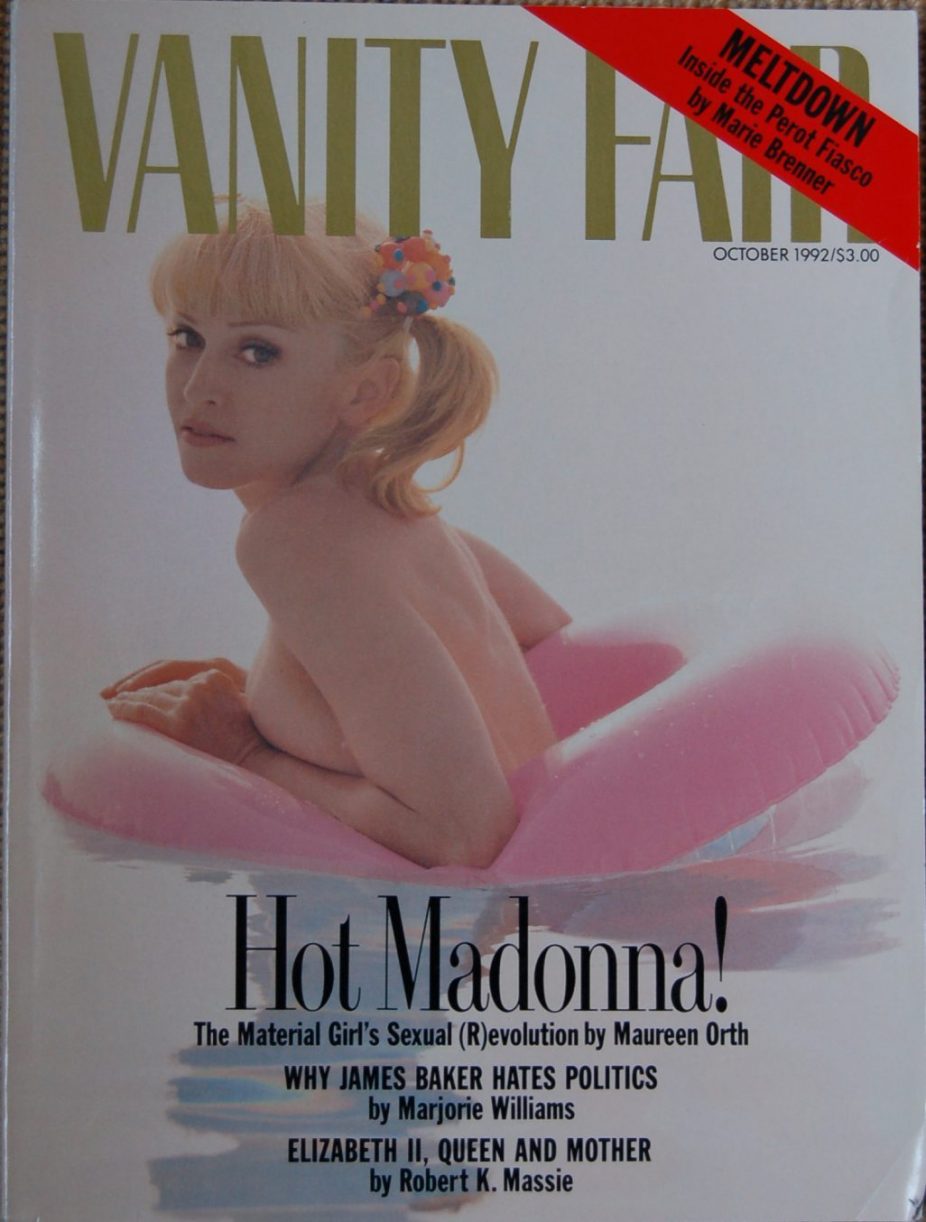

Photographs by Steven Meisel