Original Publication : Vanity Fair, September 1997

In Miami’s pagan, over-the-top South Beach, particularly among the large gay contingent, Gianni Versace had been a tanned, adored idol. Now the emperor lay dead, gunned down almost Mob-style on the steps of his lavish Mediterranean villa, shot in the head and face in broad daylight. The prime suspect, dressed in nondescript shorts and a baseball cap, came in close for the kill and then coolly walked away along Ocean Drive. He knew very well that the act of murdering Versace, the Calabrian-born designer whose flamboyant clothes virtually defined “hot,” who tarted up the likes of Princess Diana and Elizabeth Hurley but whose gowns also made Madonna and Courtney Love more elegant, would instantly catapult him to where he had always fantasized being: at the center of worldwide attention.

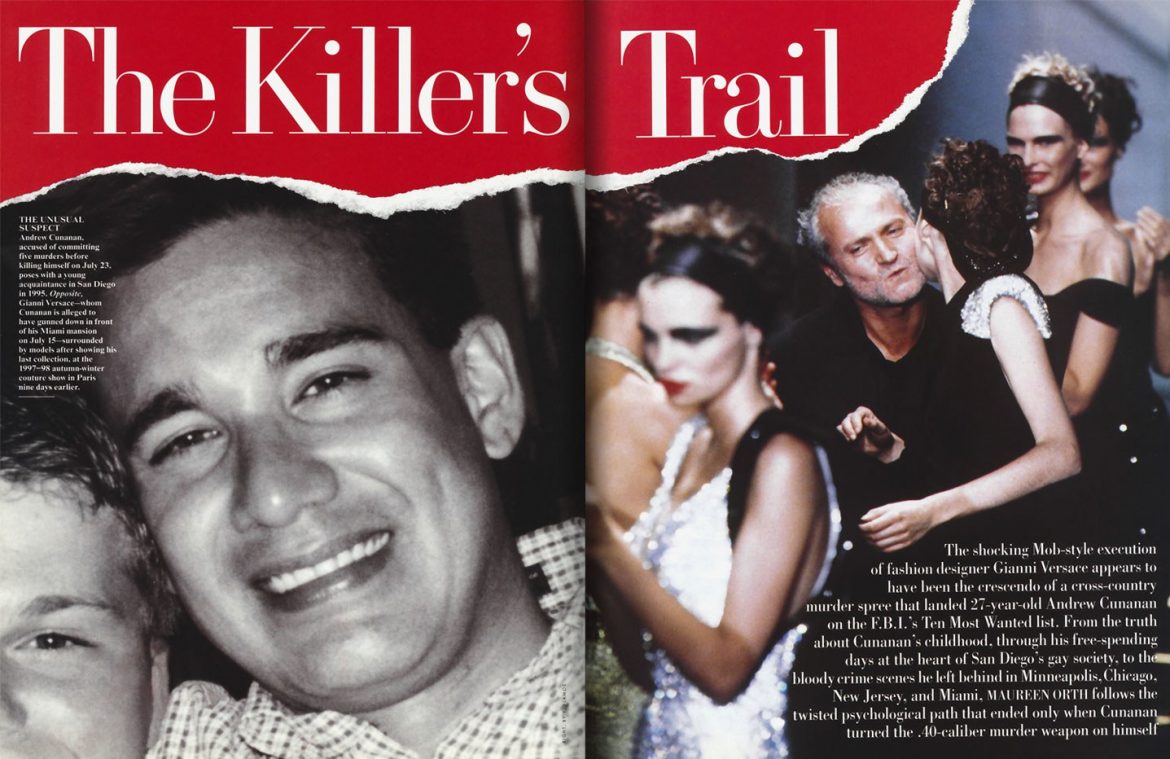

Until recently, Andrew Cunanan, 27, was just a gay gigolo down on his luck in San Diego. A voracious reader with a reported genius-level I.Q., he coveted the lifestyles of the rich and famous. He tracked possible sugar daddies with care and would say with a pout that he didn’t know whether to fly to New York or Paris for dinner. He could describe the texture and delicacy of the blowfish he claimed to have eaten at an $850 Japanese lunch. Or he could say of a work of art what year it had been painted, who had owned it through the centuries, what churches it had hung in. His wit was biting, his memory photographic. Cunanan’s story is a singular study in promise crushed.

Wherever he went, he craved the limelight and aspired to the top, whether through charm or falsehood. In the end he reached an exclusive pinnacle that provided him with the celebrity he had always sought: he became America’s most wanted fugitive. More than a dozen law-enforcement bodies, including the F.B.I., were seeking to question him not only about Versace’s murder but also about four others that took place between April 27 and May 9. The sadistic savagery of those crimes reverberated throughout America’s gay communities.

Two of Cunanan’s alleged victims, Jeffrey Trail, 28, and David Madson, 33, looked as if they had walked off a Kellogg’s Corn Flakes box: from upright, loving, midwestern families, they were intelligent, handsome, and well liked. Cunanan considered Trail, a graduate of the Naval Academy at Annapolis, to be his best friend, and referred to him as “my brother.” Madson, a rising architect, was the great unrequited love of Cunanan’s life. Although they had broken up in the spring of 1996, Cunanan still kept Madson’s picture taped to his refrigerator door.

The third victim, esteemed in Chicago political and social circles, was much older and very rich, a type Cunanan was known to research carefully. Real-estate tycoon Lee Miglin, 75, also professed to have been happily married for 38 years. The Miglin family has vociferously denied that Lee or his 25-year-old son, Duke, a fledgling actor in Hollywood who has a bit part in this summer’s Air Force One, ever met Cunanan.

The fourth dead man, William Reese, a 45-year-old caretaker of a Civil War cemetery in New Jersey with a wife and son, is considered by clinicians who study serial killers a “functional homicide.” Unlike the other victims, Reese was probably murdered simply for his 1995 red Chevrolet pickup truck. Trail, Madson, and Miglin, however, carried the personal signature of what criminologists call a “pathological, sadistic sexual offender.”

The killer’s trail ended on July 23, when a caretaker checking on an unoccupied houseboat anchored off Collins Avenue, less than three miles north of Versace’s mansion, discovered someone inside and heard a shot. He immediately notified police, who moved in a swat team and lobbed tear gas into the houseboat. It took more than 12 hours for police to announce that they had finally found the body of Andrew Cunanan in a second-floor bedroom. They said that he had shot himself in the mouth and left no suicide note. By hiding in Miami after Versace’s murder, Cunanan had broken his usual pattern of picking up a new getaway car and leaving the vehicle tied to a previous killing behind. (Subsequently the F.B.I. revealed that within 48 hours of Versace’s murder Cunanan had contacted an associate on the West Coast, asking for help in obtaining a false passport to leave the country.) Yet even as police were searching the houseboat, sightings of the suspected notorious killer who had brazenly taunted police were being called in from New Hampshire and other states. The whole country was on alert. At the time of his death, however, Cunanan had been charged only in the killings of Madson, Reese, and Miglin.

F or nearly two months before Versace’s murder, I had crisscrossed the country from San Diego and San Francisco to Minneapolis and Washington, D.C., in order to learn the real story of Andrew Cunanan, a chronic liar and consumer of status with an avid appetite for sadomasochistic pornography. “He liked S&M,” his former roommate Erik Greenman told me. “He was more the tying-up-and-whips type—just the degradation, not the asphyxiation.” The weekend before Cunanan left California for Minnesota, where he probably murdered both Madson and Trail, signs were mounting that he was spiraling out of control. On April 18, Cunanan was in San Francisco and ran into his old friend John Semerau at the Midnight Sun, a gay bar, where he showed him a flyer for an S&M party he was planning to attend the next night. The two later argued. “He grabbed me around the neck so hard he was choking me by his grip,” recalls Semerau, who angrily told Cunanan, “ ‘Andrew, you’re really hurting me—stop it!’ Something had snapped in him. Now I realize the guy was hunting—he was getting the thrill of the hunt, the thrill of the kill. I saw it in his eyes. I saw it in his body. He had stepped over the edge.”

Friends remember that Cunanan often dropped Versace’s name, and during my investigation I learned that the two men had met in the past. They had come in contact in a San Francisco nightclub, Colossus, in 1990; Versace was in town because he had designed costumes for the San Francisco Opera. That night, October 21, an eyewitness recalls, Cunanan was smugly pleased that Versace seemed to recognize him. “I know you,” Versace said, wagging a finger in the then 21-year-old’s direction. “Lago di Como, no?” And Cunanan replied, “Thank you for remembering, Signor Versace.” It is not clear that there really was anything to remember, or that Andrew Cunanan had ever been near Versace’s house on Lake Como. During Versace’s stay, Cunanan also met Eric Gruenwald, now a Los Angeles lawyer, at Colossus. Cunanan, in the company of a silver-haired gentleman, was still gushing over his Versace encounter. With characteristic hyperbole, he embellished it for Gruenwald, adding, “I said, ‘If you’re Gianni Versace, then I’m Coco Chanel!’ ”

Doug Stubblefield, a research analyst and close friend of Cunanan’s, recalls that during Versace’s visit he was walking on Market Street on his way to another gay dance club when a big white chauffeured car pulled up alongside him. Inside, he claims, were Cunanan, Versace, and San Francisco socialite Harry de Wildt. “Andrew called out, and we had a conversation on the side of the street,” Stubblefield says. “It was very Andrew to do that—have the car pull over.” Although Stubblefield is certain he saw the three, de Wildt told me the day before Cunanan’s suicide, “I categorically deny Mr. Versace, Mr. Cunanan, and I were in the same car. I have never had the pleasure or displeasure of meeting Mr. Cunanan.” De Wildt admitted, however, that he had been warned by the F.B.I. to be careful. “Mr. Cunanan’s little buddies have been interviewed,” he told me, “and they say the two people he most admired in San Francisco are Mr. Gordon Getty and Mr. Harry de Wildt.”

After Versace’s murder, the words of Chicago police captain Tom Cronin, a serial-killer expert I had interviewed, rang in my ears: “Down deep inside, the publicity is more sexual to him than anything else. Right after one or two of these homicides, he probably goes to a gay bar in the afternoon when the news comes on and his face is on TV, and he’s sitting there drinking a beer and loving it. You hide in plain view.”

Antonio D’Amico, Versace’s longtime companion, who raced to the door of the Miami mansion within seconds of hearing the gunshots, about 8:45 a.m. on July 15, said he could identify Cunanan as the killer who walked left down Ocean Drive. Other witnesses say the killer then cut left into an alley, then right down another alley, where he was captured on a hotel’s security camera. That alley was directly across 13th Street from a four-dollar-a-day municipal parking lot, where witnesses reported seeing the killer enter and apparently change clothes beside a 1995 red Chevy pickup truck, which proved to be the one that had been stolen from William Reese. It carried stolen South Carolina license plates. A garage attendant told me she had found the ticket for the truck, which showed that it had been parked on the third level since June 10. Drivers pay as they leave, and only after about six weeks does the garage begin to question whether the driver is ever coming back.

That morning, investigators say, Cunanan’s discarded clothes were found beside the truck. Among the things found inside were his passport, a personal check, and a pawnshop ticket, which was traced to a gold coin stolen from Lee Miglin’s house. Cunanan had pawned it in Miami using his own name and passport for verification. More than that, the pawnshop, as required by law with pawned goods, had submitted the ticket with a thumbprint of Cunanan’s to the Miami police a week before Versace was shot. That oversight was just one of many made by diverse authorities in the course of the investigation.

Soon details of Cunanan’s whereabouts for the two months following Reese’s murder, on May 9, began to emerge. Since May 12 he had been living under an assumed name in a low-rent, pink stucco, north-beachfront residence hotel, the Normandy Plaza, where he paid about $36 a day for a series of rooms. He left the hotel the Saturday before Versace was killed, skipping out on his last day’s rent. The night manager, Ramón Gómez, told me that Cunanan had paid in cash and had brought no one to his room. Gómez also said that Cunanan frequently changed his appearance—sometimes his hair would be jet-black, other times almost white, sometimes curly, sometimes straight. “I think he wore wigs.”

While at the Normandy Plaza, which is about four miles north of Versace’s house, Cunanan continued his practice of buying books and pornographic magazines. His meals were no longer in the three-star category but most often came from a nearby pizza place. He still went out every night, all night, “dressed to the nines,” however, and a bartender at the Boardwalk, a north-beach gay hustler bar where young men “go on the block” to strip for older patrons’ tips, told me that he had definitely seen Cunanan there. Cunanan also patronized Twist, a more upscale gay bar a few blocks from Versace’s mansion. When Versace arrived in town on Thursday, July 10, Cunanan was waiting.

“I’ve seen him two or three times in the last week,” Twist manager Frank Scottolini told me on Thursday, July 17, two days after Versace’s murder. Scottolini says he doesn’t know why, but for a fleeting second the previous Saturday night, as he glimpsed Cunanan leaving the bar, he was momentarily overwhelmed by a sickening feeling in his stomach. “I turned to the bartender and said, ‘There goes the gay serial killer.’ Then I dismissed it, like it couldn’t be true.” Scottolini and other Twist employees now say they are able to identify Cunanan on the bar’s surveillance tapes.

Next door to Twist is the 11th Street Diner, where all of South Beach, including celebrities such as Versace, mixes. The 24-hour diner is a favorite gathering spot for South Beach cops and politicians; the Miami Beach Police Department is in the municipal building across the street. “The chief of police is in here every other day,” says the bookkeeper, Alexis diBiasio. Andrew Cunanan was seen in the diner too, right under the authorities’ noses.

What is striking in tracing Cunanan’s life as a fugitive in South Beach is how easily he adapted. He was not unfamiliar with the territory. In 1992, according to a former member of a gay-escort service based in Miami Beach, Cunanan, calling himself “Tony,” worked for the service in both Florida and California. “He told me in a letter that he was tired of California,” says the former hustler, who claims he met Cunanan in the company of an older doctor from San Bernardino at a Beverly Hills show-business party in 1989. “He said there were too many other young guys there trying to do what he was trying to do.” The boss of the escort service, he says, decided to give Cunanan a chance and “referenced” a client to him in California. The boss was so impressed when Cunanan remitted the escort service’s 40 percent of the $165-a-night take from California that “he also referenced people to him in Florida.” Cunanan worked for the service, according to the former gay escort, in Florida on at least two occasions. “He said he’d go anywhere—Miami Beach, Jacksonville, Orlando.”

South Beach, in fact, is a flashier, more tropical and alluring version of the primarily gay Hillcrest area in San Diego, which, until late April, Cunanan called home.

On a Monday night in early June, I visited Hillcrest. It was a busy evening for middle-aged Mexican-American drag queen Nicole Ramirez-Murray. Wearing a red ponytail wig and a green chiffon cocktail dress, Nicole first appeared at the Brass Rail, to introduce “the Dreamgirls,” then raced down to the Hole, an outdoor bar with a shower, stage left, to hold forth at the Wet-n-Wild underwear contest. The Hole, across the street from a former Marine Corps recruiting station, gets a raucous crowd of closeted military men, openly out muscle-flexing gym rats, and a few staid elderly gentlemen from the wealthy enclave of La Jolla. They all roared when Nicole said to one shivering contestant, “You look like Andrew.” After all, this is the community in which Andrew Cunanan, the big spender with the loud, look-at-me laugh who called himself Andrew DeSilva, cut a wide swath.

“I remember the first time I ever saw Andrew, sitting on that stool,” said a tattooed waiter with spiky platinum-dyed hair at the drag show. “He was holding a paper bag stuffed with a big wad of cash, saying, ‘I’m going to buy me some drugs and sell me some drugs.’ ” That would be a typically flamboyant gesture for the young poseur who constantly claimed center stage for himself. “He was like Julie, the cruise director on The Love Boat,” said Erik Greenman, a waiter who met Cunanan the night a few years ago when Greenman arrived in San Diego from Oregon. Cunanan functioned as a virtual Welcome Wagon for new boys in town. He promptly introduced Greenman to Tom Eads, a part-time restaurant manager and student who would be Greenman’s lover for the next two years. “He was the glue that held a lot of the community together,” Eads told me. He was wearing a pair of Cunanan’s black, buckled Ferragamo shoes, which Cunanan had bestowed upon him shortly before he left San Diego on April 25. “Andrew would hobnob with the La Jolla rich and then wear his blazer to the Hole.”

Nicole Ramirez-Murray, who also writes a social column, said his mouth had dropped open to hear Andrew discussing Henry Kissinger’s role in politics with some big shots at a closeted private party during the 1996 Republican National Convention in San Diego. “He was very knowledgeable. Most young men his age I call ‘S and M’—stand and model.… He was visible at some parties he certainly shouldn’t have been at.”

He targeted people he wanted to meet. “Andrew did his homework,” said San Diego restaurateur Michael Williams. “He would investigate older, wealthy gay men who didn’t have families, and he would place himself in those circles. And that was his living.”

Cunanan was last kept with lavish indulgence—in a seaside condominium and a hillside house in La Jolla—by Norman Blachford, a conservative retired millionaire in his 60s who made his fortune on sound-abatement equipment. Blachford allowed Cunanan time with his friends, reportedly gave him $2,000 a month, and provided him with a 1996 Infiniti I30T to tool around in. They went to Paris and Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat in the South of France in June 1996, and they would fly to New York to see Broadway shows.

At Cunanan’s reported urging, Blachford had sold his home in Scottsdale, Arizona, and moved into the La Jolla house once owned by Lincoln Aston, a wealthy, older friend of Cunanan’s who in 1995 had been bludgeoned to death with a stone obelisk. A “mentally troubled loner” whom Aston had picked up was convicted in California for the crime.

Blachford is a member of Gamma Mu, the extremely private fraternity of about 700 very rich, mostly Republican, and often closeted gay men, which twice a year sponsors posh “fly-ins” to cities around the world. At Gamma Mu’s last Washington, D.C., fly-in, two years ago, members were treated to a private party in the Capitol Rotunda and a brunch on the roof of the Kennedy Center. According to one member, “The annual Starlight Ball in D.C. attracts 250 of the highest echelon of closeted Washington.”

Through Blachford, Cunanan—as Andrew DeSilva—briefly became a Gamma Mu member, and his contacts in the group afforded him access to a storehouse of privileged information. There are reports that certain members were alerted by the F.B.I. this past June and July to be on the lookout for Cunanan, who was in a position, it was feared, to blackmail them.

Ironically, the spring ’97 fly-in occurred in San Diego, just a few weeks after Cunanan had been named a suspect in the murders of Trail and Madson. There is also a large Gamma Mu contingent in the Miami–South Beach–Fort Lauderdale area. Cliff Pettit, the mover and shaker behind Gamma Mu, for example, lives in Fort Lauderdale. He stressed to me that Cunanan was no longer a member, and Art Huskey, a San Diego real-estate agent, told me that he and other members had always assumed that “Andrew was hired to be Mr. Blachford’s decorator.”

Last summer, Blachford and Cunanan shared a house in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat with Larry Chrysler, a Gamma Mu member from Los Angeles. Cunanan, Chrysler reports, said he was descended from Sephardic Jews and spent his time lying by the pool underlining passages in books, dining at the finest restaurants, and soaking up information “like a sponge.” He had an opinion on everything. One night they were discussing the Mamounia, the old landmark hotel in Marrakech. Chrysler recalls, “Andrew said, ‘Oh, nobody stays at the Mamounia anymore. It’s been redone.’ Two weeks later I pick up a magazine in the house, and there in it was the same direct quote about the Mamounia from [Yves Saint Laurent’s business partner] Pierre Bergé.”

Chrysler found Cunanan “fascinating,” if full of “BS.” Once, Cunanan came back from the village of Beaulieu with a tiny jar of jam that cost $20. “I never look at any price,” he said. “My family never looked at any price.”

On their way back from France, Blachford and Cunanan continued the swell life, spending several days in July 1996 in East Hampton as the guests of a wealthy gay couple. They attended parties and dined at the trendy restaurant Nick & Toni’s. Once again, Cunanan charmed his older companions, but he told stories that made them raise their eyebrows: he said that he had been married to a Jewish woman, and that his father-in-law was the head of the Mossad. “He was young and attractive, entertaining, good company—what’s not to like?” said one, who also found him “sad on two levels: He’s got a lot going for him, I thought. He doesn’t need all this sham.… He was also a young man ultimately with no career ambitions in any direction. He pretty much said he was interested in older men for their financial situations. He made no bones about that, and he would say it in front of Norman.”

Norman Blachford, however, apparently did look at prices, and when Cunanan left him soon after and moved in with Erik Greenman and Tom Eads, he complained that Norman was “too cheap.” The least Norman could have done, he said, was give him a Mercedes 500SL, fly first-class, and repaint all the rooms in the La Jolla house. According to Eads, “Andrew said he got tired of all Norman’s nickel-and-diming.”

Cunanan was astonished that Blachford would let him go.

It immediately becomes apparent that Andrew Cunanan rarely told—or faced—the truth about himself. To friends in San Francisco’s Bay Area in the early 90s, for example, Cunanan, then barely 20, said that he had gone to Choate, dropped out of Yale, and transferred to Bennington. In fact, he graduated from La Jolla’s private Bishop’s School and eventually spent two years at the University of California at San Diego. In Berkeley, Cunanan cultivated a “mussy professor look” older than his years. “He hung around very intelligent, talented people, because he wanted these people to be responsible to him,” says his close friend from those days Doug Stubblefield. Cunanan was then writing a book about his experiences in the Philippines, his father’s native country, which Stubblefield describes as “subtle, poetic, and filled with metaphors.”

Even then Cunanan was beginning to set his pattern as a con artist and court jester—to lie, to be glibly authoritative on art, to be witty and entertaining enough to live well without working. His first “patrons” were a young couple with a baby daughter who took him into their beautiful hillside house. Cunanan enjoyed taking their child—his goddaughter—out, and he had a passion for building dollhouses. He subscribed to a magazine on the subject and created a ruined French château complete with blackened windows.

Cunanan had known his patroness, Elizabeth Cote, since junior high school, and he would later spin a tale that he had been married to a Jewish princess and had fathered a daughter, whose pictures he liked to show. He had other stories as well. His father, he said, was a Filipino general close to ousted dictator Ferdinand Marcos, as well as a bisexual with a young lover, whom Andrew resented. “He has a car and I don’t,” he would tell friends. Cunanan boasted that he had a pilot’s license, and that a Filipino senator engaged him occasionally to fly him around in an old rattletrap Cunanan called the “Buddy Holly death plane.”

Cunanan was always known as DeSilva in San Diego, and there he told people at times that his father was an Israeli millionaire, at other times that he was a Fifth Avenue aristocrat. He never told the truth: that his father was a navy veteran and a stockbroker from nearby Rancho Bernardo who—as a lawsuit filed by his wife alleges—had been accused of embezzling more than $100,000 and who abandoned his wife and their four children in 1988.

Did Andrew’s Italian mother, who lives on public assistance, ever really “spa with Deborah Harry,” as her son liked to relate? Hardly. Yet to San Diego friends Andrew portrayed her as the ultimate spoiled Jewish mother, who stayed with his father in an unhappy marriage only so that the children would not lose their vast inheritance. In reality MaryAnn Cunanan is a devout Catholic, a bright but emotionally fragile woman. Cunanan never acknowledged to her or his sisters or his brother what they all knew—that he was gay and lived in a world apart.

Despite their misgivings, Cunanan’s friends indulged him in his stories; some still speak fondly of him as an amusing raconteur who insisted on picking up every tab and who would leave a $200 tip after a dinner for eight. “He’s still a great friend—I hope he’s O.K.,” Erik Greenman told me before the Versace murder. “He told me a story about someone he had dinner with, and I couldn’t tell him the person had been dead two years,” says a now skeptical San Diego friend, Michael Moore. “Andrew should have had a master’s in conversational utility.”

“He was so good and sincere about listening to what your situation was,” says Doug Stubblefield. “But he’d never let us in close to him.”

That was perhaps because he had so much to hide. I learned that in certain circles Cunanan apparently became a supplier of pharmaceuticals. “I once asked Jeff Trail, ‘How does Andrew get by?’ ” says Michael Williams. “Jeff said, ‘Oh, he’s up to his old profession: he sells drugs.’ ” Anthony Dabiere, a waiter at California Cuisine, one of Cunanan’s favorite San Diego restaurants, says, “I was witness to Andrew doling out drugs in bars—Percodan, Vicodin, Darvocet. He’d say, ‘This will give you an overall sense of well-being.’ We were given to understand he was using. We were also reminded that he had access to coke and high-grade marijuana as well.” Tim Barthel, co-owner of Flicks, a video bar Cunanan frequented most nights, says, “I heard he started getting into drugs himself before he left—even heroin. The last couple of weeks he was more disheveled.”

“Yes, he started dealing drugs again,” says Erik Greenman, who tells me that Cunanan had two phone listings, one under DeSilva and another, for “business deals,” under his real name. “He’d do that if he needed money. He’d never get his friends involved.… He’d come in with a suitcase, dressed up very nice. He was a deliverer. The whole thing would take a half an hour.… He knew shady characters in New York.” There wasn’t much mystery to it, Greenman implies, despite the fact that some police claimed they had no knowledge that Cunanan dealt drugs. “We all knew he did it, and he knew we all knew.”

There might even have been other criminal activities. For example, Cunanan talked about a warehouse where he could get things “that just fell off a truck”—boom boxes, cameras, liquor. Was it true or false? One friend was invited to go shopping there, but he claims to have demurred. “He ran with a crowd with illicit stuff,” the friend says. “He made many comments that he wanted to get out of it—it was dangerous.”

A month before Jeff Trail was murdered, he confided to Rick Allen, a friend in Minneapolis, that Cunanan had approached him to help him in his illegal business. Trail said he had refused. Cunanan, police assume, killed David Madson with Trail’s .40-caliber handgun, which he may have stolen from Trail’s Minneapolis apartment. “I never understood why they were best friends,” says Tom Eads. “But they were thick as thieves for so long.”

When Trail lived in San Diego, he and Cunanan would go target-shooting together. “Andrew knew calibers, sizes, weights of guns,” says Eads. Trail, who was from DeKalb, Illinois, was an excellent marksman. He had been a small-arms instructor in the navy, and had served in the Persian Gulf on a guided-missile cruiser. He left the navy as a lieutenant in 1996 and joined a training program for the California Highway Patrol. He was ambitious but responsible, always willing to help people out. He loved listening to Sinatra records, dated very young men, and was attracted to cops. In 1996 he rather abruptly resigned from the highway patrol, and eventually he found a job as a district manager for Ferrellgas, a propane retailer in a suburb of Minneapolis. According to his family and friends, Trail, the son of a mathematics professor at Northern Illinois University, was politically conservative and deeply opposed to drugs.

“What Jeff told me,” says Allen, “was ‘Andrew talked to me about doing security work for his “import-export” business.’

“I don’t even know what you’re talking about,” Allen says he told Trail.

“ ‘Drugs, Rick, drugs.’ Jeff was very hesitant to talk about it at all. He told me, ‘It’s not something I tell anybody about.’ I said, ‘What did you tell him?’ Jeff said, ‘I said, “Fuck you.” ’ ”

For all his sociability, Cunanan often griped to Tim Barthel and others that he had a hard time picking up people for sex. “My impression was that he was always going for people out of his league physically,” says Barthel. Gays in San Diego, like those in Los Angeles, are extremely body-conscious, and many of them ingest Creatine, a protein powder, one teaspoon of which, I was told, is the equivalent of two pounds of red meat. Sunday afternoon in San Diego’s Balboa Park is a gay parade of tanned, shirtless physiques playing volleyball, grooming dogs, rollerblading, and biking. Cunanan rarely did anything more strenuous than read magazines and walk Erik Greenman’s black Rottweiler, Barklee, to which he was devoted.

“He hung out with attractive younger guys, the cool ones, but physically he was not up to it,” Tim Barthel continues. “He got into those circles with money and charm—he just wiggled his way in.” Greenman agrees: “Andrew was not one to get dates. He had to flash money. A good-looking guy wouldn’t look at him.” In the 10 months they lived together, Greenman says, Cunanan never brought anyone home, which was “unheard of.”

Greenman concedes that Cunanan “had such extreme taste in sex—S&M-wise—he’d need privacy.” Meaning? “It was way past normal. Whether it’d be whips or make him walk around in shackles—who knows? He’s always had bondage videos.… He was a dominator.” In the early-morning hours of his last months in San Diego, the restless, nocturnal Cunanan, who usually slept from six a.m. to two p.m., was also, according to Greenman, injecting himself with drugs. But when the sex fantasies and the crack wore off, he would feel terrible. Ever the snob, he told Greenman, “Never do crack. It’s a ghetto drug.”

In the first week of April, Cunanan went to San Francisco, where he met 26-year-old Tim Schweger, an assistant manager in a San Francisco Denny’s, at a gay dance club. Cunanan offered to get him drugs—ecstasy or cocaine—which Schweger refused. “He said he was associated with people who dealt in San Diego,” said Schweger. “He was kind of like a middleman.” Cunanan also bragged about knowing various celebrities—Lisa Kudrow, Elizabeth Hurley, Madonna. “He said he had lunch with Kudrow the previous weekend.”

Cunanan eventually took Schweger back to the Mandarin Oriental hotel, where Cunanan liked to stay when he was in San Francisco. After that, Schweger’s memory of what took place is hazy. “I think I was drugged that night, or I had too much to drink,” he says. “But lately I’ve had these memory flashbacks of trying to fight him off during the night. I wasn’t attracted to him sexually. I woke up with three hickeys on me.” Schweger said he went to sleep in his underwear. “When I woke up, I had nothing on. After that night, I knew he had a rough side to him.”

They ran into each other again the following weekend. “He kept his arm around my neck the whole time. He started to like me, but I rejected him.” Cunanan then went on to another club, and when Schweger got there, he saw him coming on to someone else. “ ‘You’re a player, aren’t you?’ I asked him. He just laughed this sarcastic laugh.”

Schweger said Cunanan told him he was moving to San Francisco, but before that, “he said he had to go to Chicago to do some things.”

The one person who allowed Cunanan his fantasies, if only partially, was David Madson. Madson, a former ski instructor, was so charismatic that he “blew people away” both personally and professionally. He worked for the John Ryan Company in Minneapolis, designing “retail financial centers” for large banks, a $70,000-a-year position that took him all over the country. “David was an absolute joy to be around and an immensely talented person, on the precipice of becoming a leading designer in the world in his field,” says John Ryan. His friends describe him as a “peacemaker” who avoided confrontation and could always talk his way out of anything.

“He wanted to save people. He liked the underdog. David was kind of drawn to people who needed him,” says a former co-worker, Kathy Compton. “He had just seen the movie Jerry Maguire, and he said, ‘Jerry Maguire reminds me so much of me—always trying to make things O.K.!’ ”

Madson and Cunanan met in San Francisco in December 1995. “It was pretty sparky,” says a friend of Cunanan’s who witnessed their first encounter. Cunanan spotted Madson at a bar and sent him a drink. That night they had a nonsexual “sleepover” in Cunanan’s luxe room in the Mandarin Oriental. Soon they were dating long-distance, and their sex became rough.

“In the late spring of ’96, I had a conversation with Andrew about exploring the S&M thing with David,” says Doug Stubblefield. “He said he had wrist restraints, and they’d been trying it. David wouldn’t let him go as far as he wanted, but he thought it was a lot of fun.” Erik Greenman adds, “Andrew talked to me about it many times. David enjoyed it just as much as Andrew did.”

About that same time, however, at the urging of friends, Madson began to distance himself from Cunanan. He had become uneasy, because Andrew would often disappear or become unreachable. Presumably the reason for this secrecy was that Cunanan was living in La Jolla with Norman Blachford.

By September 1996, Cunanan and Blachford had broken up. Blachford let him keep the Infiniti. After staying a short time at an inexpensive residence hotel in Hillcrest, Cunanan moved in with Greenman and Tom Eads. He told them he felt that he had been rejected by Madson.

Meanwhile, Jeff Trail was also cooling toward him, telling Michael Williams, a good friend in San Diego, that he had had “a big fallout with Andrew and never wished to see him again.” Trail told Jerry Davis, a friend at Ferrellgas, that although he didn’t want Andrew to stay with him in Minneapolis anymore, “he was like a relative you didn’t like—you had to let him stay.”

By April, Cunanan, who had uncharacteristically begun drinking—$36 bottles of Stonestreet Merlot “like there was no tomorrow,” in the words of San Diego maître d’ Rick Rinaldi—was confiding to select friends that he was broke. He had stopped going into the humidor at the cigar store Bad Habits for eight-dollar cigars, and he said that he might actually have to go to work. About the only legitimate job he had ever held was as a Thrifty Drug Store cashier, when he lived with his mother in a small, $750-a-month condominium in Rancho Bernardo in the early 90s.

Cunanan next decided to relocate to San Francisco, and he was successful in convincing David Madson that Madson was responsible for his moral turnaround, which included the decision to find legitimate work. Madson proudly told friends that Andrew was going to give up his shady business and materialistic ways.

Over the Easter weekend, Cunanan went to Los Angeles with Madson and a young engaged couple, Karen Lapinski and Evan Wallit, who were friends of Madson’s from San Francisco. Cunanan insisted on taking two $395 rooms at the Chateau Marmont and persuaded Madson and the couple to stay there with him. He and Madson had supposedly not had a sexual relationship for almost a year, and Madson later claimed that they had argued when he refused Andrew’s advances.

A few days after Easter, Cunanan was in San Francisco, staying with Lapinski and Wallit. Cunanan told the future bride, who had asked Madson to give her away, that he would pay for the wedding reception. He told her, police say, that he had $15,000 he had to spend before tax day, April 15, and he gave her and Madson expensive leather jackets. He also gave Madson a suit.

Before moving to San Francisco permanently, Cunanan told friends, he had some unfinished business to take care of with Jeff Trail. According to Minnesota police, Lapinski later told the F.B.I. that Cunanan had also said that he was going to start a business making prefabricated movie sets with a friend named Duke Miglin.

At Cunanan’s farewell dinner in San Diego on April 23, at California Cuisine, his favorite waiter, Anthony Dabiere, wrote in raspberry purée around the edge of his plate, “Goodbye to You.” In his toast, a somewhat somber “DeSilva” said he was feeling bittersweet about leaving. What he was going to miss most, he said, was Barklee, Greenman’s dog.

Nobody would have guessed, to hear him, that he had bought a one-way ticket to Minneapolis.

The last thing in the world Jeff Trail or David Madson wanted was a visit from Andrew Cunanan. Nevertheless, neither appeared capable of confronting him directly. “No one would ever tell Andrew to his face—they didn’t want to hurt him,” says Casey Murray, one of Trail’s former boyfriends. And though Madson was at least two boyfriends away from Cunanan by the end of April, he continued to accept gifts from him.

Trail had made it clear that he wouldn’t be around much the weekend of Andrew’s visit. His boyfriend, Jon Hackett, a student at the University of Minnesota, was celebrating his 21st birthday, and Trail was taking him out of town Saturday night. Trail was known to have warned Madson, who had befriended him casually when he moved to Minneapolis late last October, that Cunanan was a liar. “You can’t believe a word he says,” Trail declared. “He’ll say anything to get a reaction.” Meanwhile, Cunanan had told a friend that he was uncomfortable having the two people he cared most about living in the same faraway city without him.

“David was apprehensive about Andrew’s visit,” says Cedric Rucker, a college administrator who was one of Madson’s last boyfriends. “He held suspicions that Andrew was involved in the international drug trade, bringing drugs into the country from across the Mexican border. He probably had ties to organized crime. I said, ‘Why would you want to be affiliated with this?’ He said, ‘Because he’s trying to make a change in his life. Andrew just needs help.’ ”

Cunanan may have been jealous, or suspicious that Madson and Trail were gossiping about him behind his back. He may also have been angry at Trail for refusing to work with him. In any event, Cunanan told Madson, who confided to those close to him, that Trail was mixed up in the drug trade with him. “J.T.” had been forced to flee California, he said, because of an impending investigation. Police say they know of no such investigation ever being instigated.

Rob Davis, a handsome black businessman who succeeded Cunanan as Madson’s boyfriend, heard the story at a Christmas party. “Andrew told David that he and Jeff had gotten mixed up in some cocaine deal that had caused Jeff to resign from the California Highway Patrol, because Andrew had gotten Jeff to transport cocaine across the border.”

“Jeff started getting scared, and he left—he didn’t want to get involved,” said another friend who had heard a similar story from Madson. Madson also confided that Andrew had bragged about getting someone killed the day the person left prison, because he had ratted on a friend of Andrew’s. “Andrew also talked about having millions confiscated from foreign bank accounts through F.B.I. subpoenas or warrants,” says the friend. “He told David that was what made him change his mind—he came so close to losing everything that he decided to go straight.” Cunanan’s exact words, according to the friend, were “You just don’t walk out on the Mob.” If Cunanan had any credibility, these stories would be chilling.

People who knew Trail—who rarely drank, never smoked, and was staunchly opposed even to pot—say the scenario is preposterous. Trail’s closest friend, Jon Wainwright, a real-estate-development executive in San Diego, called the accusation inconceivable, but added that he never understood why Jeff quit the California Highway Patrol. “I tried to talk him out of it.” Trail’s explanation, say his friends, was that the C.H.P. involved too much paperwork, that he was taken aback by the “redneck attitude” he had encountered on a “ride-along,” and that it was too easy to get shot at.

“There was some strange bond there between Andrew and Jeff,” continues Wainwright. “Andrew would hook up people for J.T. It was kind of strange, actually. My belief is that Andrew was very infatuated with Jeff.” The two had apparently never been intimate, but Cunanan was able to get Trail to do his bidding. At his birthday party last year, to impress Norman Blachford, Cunanan gave Trail the gift he wished Trail to present to him, and told him to wrap it and to say he was an instructor at the California Highway Patrol. Trail did as Cunanan asked.

Doug Stubblefield remembers a dinner in San Francisco last summer with Cunanan, Trail, and Madson at which Cunanan exclaimed that “Jeff was his oldest friend from kindergarten or first grade. Jeff said, ‘I grew up on the other side of the tracks, but I know everything about him.’ Andrew said, ‘If you want to get the real scoop, go to Jeff.’ ”

Trail and Cunanan had actually met several years earlier, in San Diego. Last summer Trail informed aspiring writer Daniel O’Toole, his boyfriend at the time, that Cunanan was beginning to annoy him. “Jeff told me they’d be out in public and Andrew would tell his stories and put Jeff into them and Jeff didn’t want anything untrue said about him. Andrew would embarrass him in public.” O’Toole couldn’t understand why Trail put up with it. “Andrew was aggressive, obnoxious, and domineering a lot of the time, and it got on Jeff’s nerves,” he says. “But Jeff said he felt sorry for him. Andrew thought he was Jeff’s best friend, but Jeff didn’t think Andrew was his.”

According to O’Toole, Cunanan took him out in San Francisco one afternoon last summer and got him drunk. He had O’Toole accompany him to pick out some hardcore S&M videos, and he showed him pictures of Madson, “the man of my dreams, the man I want to marry.” Trail was furious. After seeing the covers of the videos, O’Toole says, “I made sure I was never alone with him in the same room again.”

On Friday, April 25, David Madson dutifully picked Cunanan up at the Minneapolis airport. Yet at dinner with several of his friends from work that night, Madson appeared uncomfortable. “Show them what I got you,” Cunanan urged. He had brought Madson a gold Cartier watch. It was “not new,” Madson told them, just a thank-you from Andrew for helping turn his life around.

During dinner Cunanan, who mentioned that he planned to return to California Monday morning, was up to his old tricks to impress new people. He mentioned the Rolls-Royce he had driven around in as a kid. He informed one woman he had a company—as Norman Blachford had once had—that made sound-abatement equipment for movie sets. Later, at a camp polka palace, Nye’s Polonaise, where he and Madson met Monique Salvetti, Madson’s best friend, for a drink, Cunanan told her that he was setting up a factory in Mexico to make prefab movie sets, a profession similar to that of a friend of his in San Diego. This time, however, he did not mention the name Duke Miglin.

Cunanan presumably spent Friday night at Madson’s apartment. Monique Salvetti talked to Madson around 10 a.m. on Sunday, and he said he and Andrew had gone out to dinner again the previous night. “Is everything going O.K.?” Salvetti asked. “Yeah,” he said. They made plans to meet later that day, but she couldn’t reach him. That was Madson’s last known telephone conversation.

Cunanan apparently spent Saturday night in Trail’s apartment, in nearby Bloomington, entering with a key left for him under the doormat. He was there at 10 a.m. on Sunday, when he politely took a phone message for Trail from Trail’s friend Jerry Davis about a softball game. He left it on a yellow pad and signed it, “Love, Andrew.” Trail went to the three o’clock game but left early to bake a cake, because, he said, friends were coming over to celebrate Hackett’s birthday. He did not mention that he had seen Cunanan.

That afternoon Trail told Hackett that he needed to talk to Andrew about something “pretty important,” which would take only about a half-hour. “Jeff didn’t say he knew what it was about,” Hackett told me.

When Hackett arrived at Trail’s apartment at six p.m., there was no sign of Cunanan or his bags. About eight o’clock, though, Cunanan left a voice message without identifying himself, just giving Madson’s number and saying, “Give me a call, because I’d like to see you.”

Trail thought of blowing Cunanan off entirely and suggested to Hackett that they go to a movie, but Hackett said he wanted to dance on his birthday. Trail said he would meet Andrew in a coffee shop and then rendezvous with Hackett between 10 and 10:30 at the Gay Nineties nightclub nearby. Trail left in his car between 9 and 9:15.

The caller ID on Madson’s telephone, connected to his loft’s intercom, shows that someone—presumably Trail—was admitted to Madson’s apartment at 9:45 p.m. A neighbor recalled hearing shouting and somebody saying “Get the fuck out,” shaking and thumping against the wall for from 30 to 45 seconds, then water running. He looked out his door but saw no one. On Monday, another neighbor saw Madson in the elevator with a man matching Cunanan’s description. On Tuesday, yet another neighbor saw the two men walking Prints, Madson’s Dalmatian.

Meanwhile, since Trail had not shown up at the Gay Nineties, Hackett was beside himself with worry. When Jeff did not return to his apartment Monday morning, he says, “I immediately starting calling hospitals and the jail.” He paged Trail every 20 minutes. When Trail did not show up for work, Hackett called the police. “They advised me that Jeff was a big boy—28.” Unless Trail’s parents authorized it, they would not file a missing-person report for 72 hours. Hackett was hesitant to call Trail’s parents, because Trail had never told them he was gay.

Monday night about eight, Hackett returned to Trail’s apartment to find it just as he had left it. Unbeknownst to him, police say, an upstairs neighbor had seen a man matching the description of Cunanan in front of the apartment and heard voices talking inside between 7 and 7:45 p.m.

About 1:45 on Tuesday afternoon, April 29, two women who worked with Madson went to his loft, because he had not shown up for work for two days and clients were clamoring to talk to him. When Laura Booher knocked, she thought she heard whispering behind the door. Although the dog was pawing and scratching, no one answered. “We said in a very loud voice that we better call the police—I’m sure they heard me,” says Booher. When the police arrived, they said that in the event of a forced entry, if the dog became aggressive, they would have to shoot it.

At that the women backed down, and instead left a message for the superintendent, asking her to go into the apartment with her passkey. When the superintendent entered, about four p.m., she saw a body wrapped in a carpet. Blood was splattered all over the back of the door, and there were two sets of bloody footprints on the floor. She called the police, who found Madson’s dog calm; there were no feces or urine anywhere. Madson’s wallet and a bloody Banana Republic T-shirt had been left behind, and they found two plates of rice in the refrigerator. A bloody household hammer was on the table by the door.

Monique Salvetti, who is a public defender, stopped by Madson’s after work to check on him, and found police swarming outside the apartment. “I can identify the body,” she told them, assuming, as they did, that the body was Madson’s. But the police would not allow her to enter the crime scene.

By Tuesday night Jeff Trail’s parents had been contacted—they had been at the hospital where one of Jeff’s sisters was having a baby—and a metro-wide missing-person report had been filed. Trail was not identified as the body in the rug until Wednesday morning—by the tattoo of the cartoon figure Marvin the Martian on his left ankle—although his wallet, with his identification and picture, was on him. His face was badly beaten. Police had kept Monique Salvetti, who could also have identified Trail, nearby for hours but still would not let her into the crime scene. Early on Wednesday they admitted to her that the body was probably not Madson’s.

Trail had been hit from behind, and his face had been bludgeoned multiple times with a hammer. His Swiss Army watch had stopped at 9:55 p.m. Cunanan and Madson had vanished. To the horrified disbelief of all who knew him, Madson immediately went from being the supposed victim to being a suspect for murder. “My first thought: it’s Madson,” says Minneapolis police sergeant Robert Tichich, of the homicide division. “It’s his apartment. There’s a body in there. There’s no way to pin it on Cunanan as opposed to Madson.”

As a result of Madson’s new status, his parents weren’t even told he was missing until late Thursday afternoon. Instead, the police staked out the parents’ house. Between Tuesday and Friday, when Madson’s red Jeep Cherokee with a Vail bumper sticker on the back was spotted moving erratically on Interstate 35 going north—speeding up and slowing down as if the driver, presumably Madson, was trying to attract attention—there are no reported sightings of Cunanan or Madson. On Friday afternoon, the two stopped to eat at a diner near Rush Lake, in Chisago County, about an hour’s drive north of the Twin Cities.

“From Tuesday early a.m. till Saturday, it’s a big gray area,” says Investigator Todd Rivard of the Chisago County Sheriff’s Department. Minneapolis police believe the two may have gone to Chicago, and there are reports that a receipt for a Chicago parking-lot ticket from early that Friday was found in Madson’s Jeep. “I think there’s a good possibility they were out of town during that week,” says Tichich. But Chicago police have kept such a tight lid on their case—possibly to protect the reputation of the influential Miglin—that they won’t share any information. “We got no reports, not even verbal; we heard nothing,” says Rivard.

Madson’s body was found in tall grass at the edge of Rush Lake by fishermen on Saturday morning, May 3. He had been shot three times, through one eye and in the head and back. A .40-caliber Golden Saber bullet was found in his chest. His car keys were on the ground, but his Jeep was gone. According to Investigator Rivard, Madson’s body showed no sign of restraints, and his only defensive wounds were in his fingers—possibly he raised his hands to deflect a shot to the face.

Meanwhile, according to John Hackett and Trail’s co-worker Jerry Davis, Minneapolis police did not take Cunanan’s voice message off Trail’s phone for a week, although both Trail’s and Madson’s friends informed them that the major link between Trail and Madson was Cunanan. Not until one week later was a box of ammunition found in Trail’s closet that matched the .40-caliber bullets Madson was shot with.

Another box of the same bullets—with 10 missing—and an empty holster were also found in a duffel bag in Madson’s apartment. The police asked Monique Salvetti to identify the bag. “Have you looked at the identification tag?” she asked, indicating a label that was enclosed in a grip around the handle. When they opened the tag in front of Salvetti, there was the name of its owner: Andrew Cunanan.

It was not until two months later, in late June, that police recovered Cunanan’s toiletry kit from Madson’s apartment. They had also overlooked a pair of blood-spattered Levi’s, size 36, which were heaped in a corner near the sleeping area. (Madson was a size 32.) By then any shred of evidence was crucial, because the police had not been able to match any of the fingerprints taken from the various crime scenes and vehicles with the sole thumbprint they had of Cunanan from his California driver’s license. Since he had no criminal record, he had never been fingerprinted.

What police had not overlooked, however, was a pair of handcuffs, which led Sergeant Tichich to confirm that there was evidence in the apartment “to corroborate S&M activity. It was well known that Madson was involved in S&M, and so was Cunanan, and that it had gone on a long period of time.” Nevertheless, nationwide attention began focusing on Cunanan only after the next killing.

Lee Miglin’s body was discovered by police under a car in his garage off the Miracle Mile in Chicago on Sunday, May 4. The murder was brutal and had grisly, ritualistic overtones: Miglin’s hands and feet were bound, and his body was partially wrapped in plastic, brown paper, and tape. His face was taped except for two airholes at the nostrils. His ribs had been broken, and he had been tortured with four stabs in the chest, probably with garden shears. His throat had been cut open with a garden bow saw. According to friends, however, the autopsy revealed no sexual molestation.

There had been no forced entry into Miglin’s Gold Coast town house. His wife, Marilyn, had been out of town, and the message she left to say that she would be returning early Sunday morning had been played. When Miglin did not appear at the airport to pick her up, she went home to find a door open and what looked like a gun in the bathroom. She called the police.

The murderer had slept in Miglin’s bed, left a half-eaten ham sandwich in the library, bathed in the sunken bathtub, and shaved in the white-marble bathroom, leaving beard stubble on the floor and a toy gun on the sink, almost as if to taunt the police. The dog, a Labrador named Honey, which had been there the whole time, was calm and unharmed. Between $8,000 and $10,000 in cash and several of Miglin’s suits were missing. “There was a horrible feeling in the house,” says writer-socialite Sugar Rautbord, a close friend of Marilyn Miglin’s, who went immediately to the residence. “Everywhere you turned, there was evidence. We couldn’t touch anything.”

The garage, from which Miglin’s Lexus had been taken, is across an alley, separate from the town house. “It was like being back in Vietnam, a real battle scene, a highly emotionally charged environment,” says Miglin’s partner, Paul Beitler. “I saw people’s lives destroyed in front of me.”

Lee Miglin and his wife, Marilyn—a former dancer who founded a cosmetics company and became a Home Shopping Network celebrity—were much loved in Chicago for being modest, philanthropic, self-made. “Lee epitomized the American Dream,” says Beitler. “The man never had a failure.” The son of a Lithuanian coal miner in southern Illinois, Miglin rose from selling pancake mix out of the trunk of his car to become with Beitler the developer of some of the biggest buildings on the Chicago skyline; on his own he developed much of the commercial area at O’Hare Airport. There is even a smart shopping street named Marilyn Miglin Way on Chicago’s Near North Side. On that street, her boutique faces Versace’s.

Few, including Andrew Cunanan, who often traveled to Chicago and never forgot a name, could miss the crowing billboard on the Kennedy Expressway into the city from O’Hare depicting the Wizard of Oz’s Emerald City: if miglin-beitler had managed emerald city, dorothy would never have left. Moreover, in Cunanan’s San Diego apartment was a 1988 Architectural Digest featuring the Beitlers’ house.

Rumors started flying around the Hillcrest area that Andrew Cunanan knew Duke Miglin, 25. Certainly the younger Miglin was someone Cunanan would have liked to brag about knowing: he was handsome, he drove a fast car and flew airplanes—he had spent two years at the Air Force Academy—and his father was a multimillionaire. The rumors, in the form of a quote from a Hillcrest bookseller, promptly appeared in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. The same day, however, the bookseller, Bruce Kerschner—who later told me that he had merely confirmed that he had heard the same rumors—claimed in a press conference that he had been misquoted.

“We have no idea how Duke Miglin’s name surfaced. We can say with absolute certainty neither Duke nor anyone in the family knew Cunanan,” says Paul Beitler. “We sat him down and said, ‘O.K., here’s where the rubber meets the road. Tell us now if you have ever had a homosexual relationship, a secret life.’ He has told us unequivocally he’s not gay and he has had no gay relationship.” According to Minneapolis Homicide’s Sergeant Tichich, Chicago police haven’t gone near Karen Lapinski’s report to the F.B.I. that Cunanan had told her he was going into business with Duke Miglin. “It’s just sitting there.”

Another disturbing detail surfaced in the San Francisco Examiner, which quoted Stephen Gomer, an accountant friend of Cunanan’s from San Francisco, who saw him there the weekend before he left for Minneapolis. “He expressed to me his interest in sadomasochistic sex.… He was into Latex, face masks with just the nostrils showing through.”

Chicago police did not find Madson’s Jeep—illegally parked with multiple tickets “85 paces” around the corner from Miglin’s house—until midnight on Tuesday, May 6. There was no blood inside, but there was a tourist pamphlet with a line drawn around the North Side’s gay “Boys Town” area, and newspaper clips about Trail’s and Madson’s murders. By then, it appears, Cunanan, the presumed driver of Miglin’s dark-green Lexus, was far away. Police now have evidence that Cunanan was in New York City May 5, 6, 7, and 8.

An activated car phone in the Lexus was used three times the following week in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia police confirmed a news report of the attempted phone calls, angering Chisago County sheriff Randall Schwegman, who told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, “Everyone who was working on [the case] was outraged. Once he heard that, he’d have been a fool to use a phone after that.”

Friday evening, William Reese, 45, did not come home from work on time. Finns Point National Cemetery in Pennsville, New Jersey, where he cared for the grounds, is a remote historic site where Confederate prisoners were held during the Civil War. It is not far, however, from a junction of several highways, including a bridge to Delaware and a turnpike to Philadelphia.

Knowing Reese to be punctual, his wife drove from their home in Bridgeton, New Jersey, to check on him. When she arrived at the cemetery, she saw a dark-green Lexus but no sign of her husband’s bright-red 1995 Chevy truck. The door to the caretaker’s office was open, and a radio was playing. She called the police.

They found Reese in a pool of blood on the concrete floor of the basement. He had been shot once in the head with a .40-caliber bullet which later proved to have come from the same gun that killed Madson and Versace.

Meanwhile, police did not search Cunanan’s San Diego apartment until after this fourth killing. By then, he was apparently on his way to Miami.

‘These guys are very cunning predators. They have an ability to cut a victim out of a herd—much like those nature documentaries you see on TV where the tiger picks one zebra to hunt. They have this innate ability to sense who’s vulnerable,” says Gregg McCrary, senior consultant of the Threat Assessment Group and former supervisory special agent of the F.B.I.’s Behavioral Sciences Unit.

Professionals who study the psyches of serial killers say that a number of the intriguing questions surrounding this case can be understood by the traits that many of these killers display.

For example, what is the motive for all these killings? “For all I know, this violence came out of the blue,” says Sergeant Tichich. If David Madson was not an accomplice in Jeff Trail’s murder, why would he have stayed in his apartment so long with Cunanan and the dead body? “There’s all this evidence they tramped around in blood and had taken measures to conceal this body,” Tichich says. “You have to believe he was able to control Madson for extended periods of time without possibility of escape.”

But wouldn’t Madson try to escape? “It’s not surprising David stayed with him and he sat with the body for two days. Not at all,” says Chicago Police captain Tom Cronin, also a graduate of the F.B.I. Behavioral Sciences Unit. “It makes perfect sense to David: this guy’s got power over me, I can’t leave. The killing itself shows how powerful he is.” McCrary agrees: “It is to a degree the Stockholm syndrome. These sexually sadistic offenders have that ability to control people—not necessarily physical control. Many times it’s just out of fear.”

Trail and Madson had gone far beyond what their friends thought necessary in placating Cunanan. Is being a nice person a weakness? “Yes,” says McCrary, “when you’re dealing with a pathological sexually sadistic offender.” It is not by accident that Cunanan constantly seeks to put people in his debt. “They have a sixth sense of who they can manipulate and control,” McCrary says. “Their interpersonal skills are so strong, and their ability to target these victims, to understand their needs, to meet these needs and fulfill them, are so developed that in return these victims always feel obligated.”

But when does murder come in? “When he realizes that in spite of his best efforts he is not getting what he wants. He’s not going to get this guy back, for example, so he can either forget about it and walk away from it or—those predisposed to homicidal violence—kill just to settle the score. Homicide is an attempt to regain control over the situation.”

“They don’t get dumped. They go to great pains to win someone back just so they can dump back in the future. They’re control freaks,” says Cronin. “Their behavior is such that they corral people into making them the center of attention.”

What triggers the violence? “The trigger can be anything—to him at the moment it’s rational,” says Cronin. “It was the straw that broke the camel’s back—you don’t know how heavy that straw is, because you don’t know what else is on the camel’s back. The first killing he probably fantasized for years. These people are very good at planning things out. It’s no accident there’s not a lot of physical evidence. These are the actions of a very cold, calculating individual.” Often, says Cronin, they consider themselves much smarter than the police.

Sergeant Tichich acknowledges how hard it would have been to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Cunanan acted alone in the killing of Jeff Trail. “You’ve got the murder weapon there. You got the body, bloody clothes—everything you could basically ask for in a murder case is there. The only thing you don’t have is a video recording of what happened. And in this case that’s about what’s necessary.”

Sex is often a strong element in these crimes. The offenders need to act out their sadistic fantasies, says McCrary, and they repeat them till they get it right. “Typically, they have compliant victims—they begin with sex partners who were complying with their fantasies. They get someone to go along with bondage and torture until the victim won’t go along anymore, so the sadistic offender is not satisfied. By the time they reach their late 20s and early 30s, they’ve developed their sadistic fantasies. They’re really vibrant at this point, and they need to act out these things, and they can’t find people to go along with them. So now they find an unwilling victim to abduct, rape, or murder. There’s a much higher rate of homicide if torture is acted out against the will of the other individual.”

McCrary says the motives here can be mixed—both sexual gratification and the extortion of money. What was done to Lee Miglin, for example, “is a window into his fantasy.” Both Miglin and Trail were wrapped up, but “the hammer to the face [of Trail] is very personal. The destruction of the face is many times the personality of the victim—they want to destroy the person outright. The mask is depersonalization.”

Could Lee Miglin’s murder have been completely random, as his family maintains? “Why would Cunanan go to Chicago, find Miglin, and torture him without some motive?” asks Chisago County investigator Rivard. He wouldn’t, say McCrary and Cronin. “I’d say it’s highly probable that he knew Miglin,” says McCrary. “Would this guy let some stranger in off the street? The answer is no. Either [Cunanan] knew of the guy or knew his son. The idea that he just picked him up off the street and stalked him and tortured him and then killed him is bizarre—not the most likely scenario.”

Despite Cunanan’s reputation for pathological lying and drug dealing, none of the scores of people who saw him out in the bars and restaurants night after night, loud and laughing, thought he was capable of violence. Yet there were signs that he was perfectly capable of it. I spent one revealing afternoon in Rancho Bernardo, the retirement community pressed between freeways in the foothills northeast of San Diego. There I found the life to which Andrew Cunanan was really accustomed.

I visited the neat white stucco complex he called home and, after ringing a few doorbells, entered the small rented condominium on the second level facing a golf course where he lived with his mother between 1991 and 1994. There, instead of Armanis and Ferragamos, he wore the red apron of a Thrifty Drug cashier and actually did an honest day’s work. But it didn’t take long for neighbors to reveal to me that Andrew had once slammed his mother against a wall so hard that he dislocated her shoulder.

The parish priest, Father Bourgeois of San Rafael Church, told me, “He had some really weird moments—not normal as a son. To inflict physical pain on your mother—he did bruise her arm and dislocated it. She was wearing a sling.” Father Bourgeois blamed it on drugs. Cunanan’s mother, he said, had explained that at 18 “Andrew went up to San Francisco when his father left, joined the gay community, and became someone totally different.”

Lots of young men leave home in a similar way without ending up on the F.B.I.’s Ten Most Wanted list. But Cunanan soon began a long slide into sadism and desperate, attention-grabbing gestures that were rarely called into question. Last November in Minneapolis, for example, Cunanan was far more upset that David Madson had a new boyfriend than he let on. Madson, typically, thought they could all just be friends. To call attention to himself at a party Madson was hosting in his loft before an aids benefit, Cunanan set a paper plate piled with napkins on fire and then walked away from the table.

One guest at the party reportedly revealed that when he and Cunanan had gone to his apartment the night before, Cunanan bit him so hard on the chest that he threw him out.

Three months before he left San Diego, Cunanan said to his roommate, “Erik, I’m unhappy.” Greenman says, “Then he’s up and gone. He’d give you a glimpse, and then he wouldn’t.”

“He seemed a little lost,” says Michael Moore. “Jumpy.” He would assemble people “for a several-hundred-dollar dinner and then walk away to buy magazines on cars and architecture and read them at the table.” Toward the end, he said, Cunanan was down-and-out.

Although Cunanan had invited the guests to his farewell dinner the night before he left for Minneapolis, he said he had no money to pay for it. Friends picked up the tab. Erik Greenman told me that Cunanan had recently gone on a wild spending spree. In a six-month period, from approximately October to April, he had spent about $85,000—$15,000 he reportedly got from Blachford, the money he got from the sale of the Infiniti and from a loan he took out, and the rest in charges on his credit card.

Now thoughtful friends are asking themselves whether they should have allowed Andrew to get away with so much for so long. “It breaks my heart. None of us could see it, or wanted to see it, or wanted to help,” says Tom Eads. “I feel a lot of guilt.” Both Eads and Greenman received lots of presents. Cunanan gave most of his clothes away before he left for Minneapolis. He gave a watch off his wrist to Eads, saying, “Have it. This is just my beach watch. I’ve got my Cartier.” Eads accepted the gift, he says, “even though in my heart of hearts you knew he shouldn’t be doing this.”

No one called Cunanan on his lying, either. A friend from San Francisco says, “I see now that I sent a strong signal to him: It’s all right if you don’t tell the truth about yourself. I’m not here to judge you. I’m here to see that you’re funny and inventive, or whether you ever bore me. And if you do, we probably won’t be friends.” Why would you do that? I ask. “Because it helped the moment.”

In the aftermath of the Versace murder, a media maelstrom engulfed the case. Hundreds of sightings were called in from all over the country, and fear gripped the communities where Andrew Cunanan had spent time. In San Diego a somewhat dubious story had it that Cunanan was possibly HIV-positive and killing for revenge. Police warned that he might be disguising himself dressed as a woman. As news of his suicide spread, the airwaves were filled with relieved gays who felt they could march without fear in Gay Pride celebrations the following weekend in San Diego.

On August 31, Andrew Cunanan would have been 28 years old. Sadly, he never heard the emotional plea videotaped the day he died by his longtime friend Elizabeth Cote, whose little girl was his goddaughter: “Grimmy says she loves her Uncle Monkey and hopes you’ll remember that always. Your birthday will soon be here and the day after, someone else who loves you will be five years old. Please let those be days of relief.” The message ended with Dominus vobiscum. Andrew Phillip Cunanan had once been an altar boy.

Vanity Fair September 1997