Original Publication: Newsweek, January 6, 1975

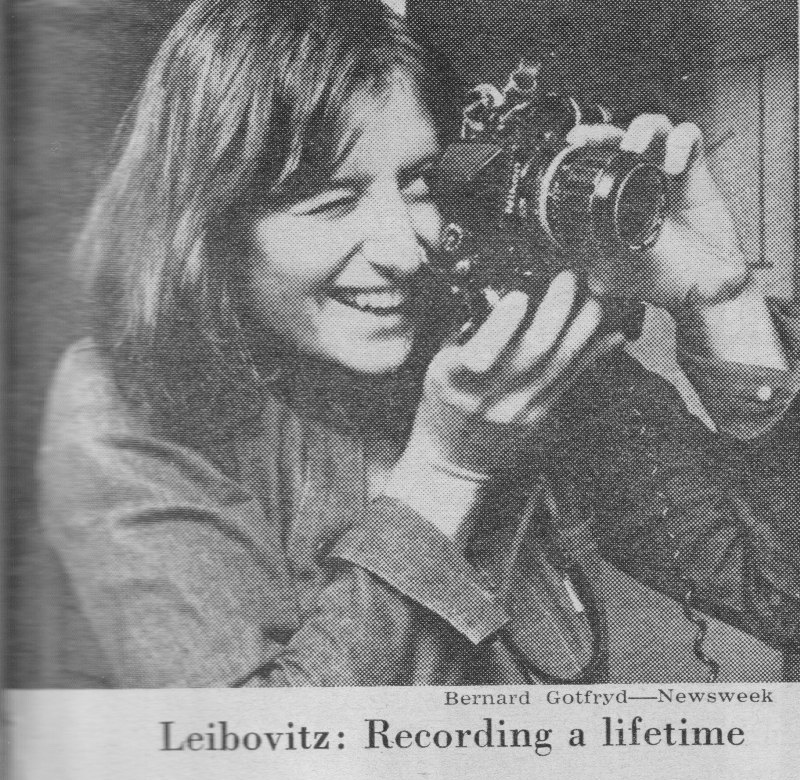

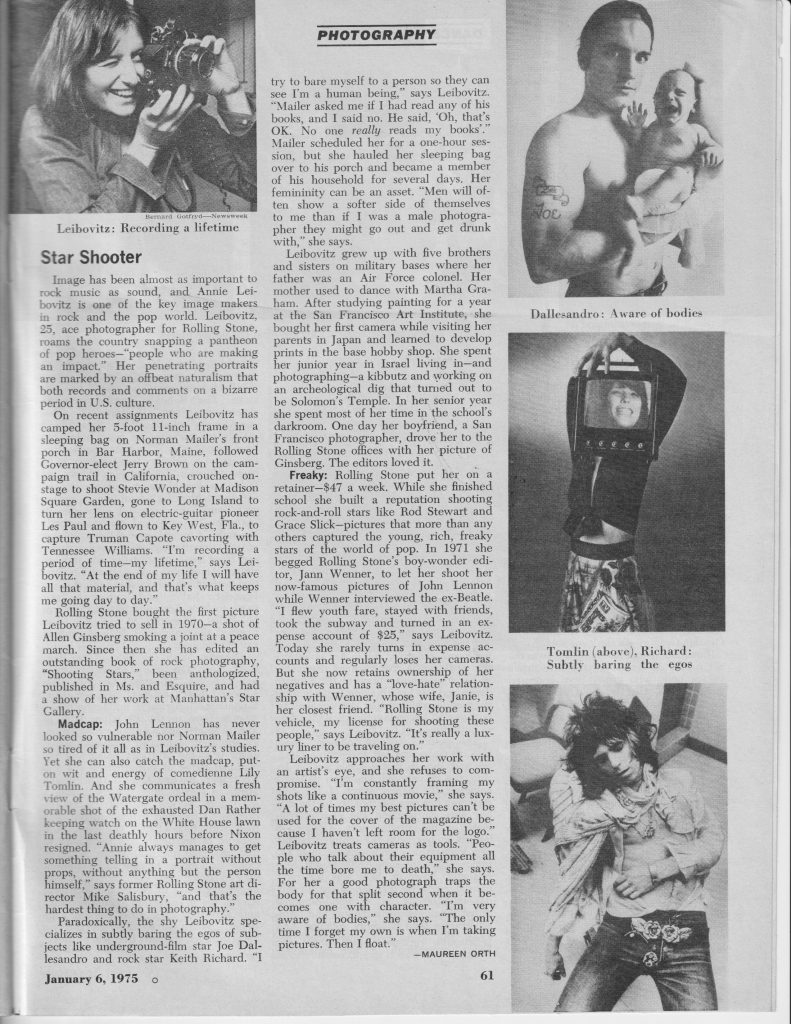

Image has been almost as important to rock music as sound, and Annie Leibovitz is one of the key image makers in rock and the pop world. Leibovitz, 25, ace photographer for Rolling Stone, roams the country snapping a pantheon of pop heroes – “people who are making an impact.” Her penetrating portraits are marked by an offbeat naturalism that both records and comments on a bizarre period in U.S. culture.

On recent assignments Leibovitz has camped her 5-foot 11-inch frame in a sleeping bag on Norman Mailer’s front porch in Bar Harbor, Maine, followed by Governor-elect Jerry Brown on the campaign trail in California, crouched onstage to shoot Stevie Wonder at Madison Square Garden, gone to Long Island to turn her lens on electric-guitar pioneer Les Paul and flown to Key West, Fla., to capture Truman Capote cavorting with Tennessee Williams. “I’m recording a period of time – my lifetime,” says Leibovitz. “At the end of my life I will have all that material, and that’s what keeps me going day to day.”

Rolling Stone bought the first picture Leibovitz tried to sell in 1970 – a shot of Allen Ginsberg smoking a joint at a peace march. Since then she has edited an outstanding book of rock photography, “Shooting Stars,” been anthologized, published in Ms. and Esquire, and had a show of her work at Manhattan’s Star Gallery.

Madcap: John Lennon has never looked so vulnerable nor Norman Mailer so tired of it all as in Leibovitz’s studies. Yet she can also catch the madcap, put on wit and energy of comedienne Lily Tomlin. And she communicates a fresh view of the Watergate ordeal in a memorable shot of the exhausted Dan Rather keeping watch on the White House lawn in the last deathly hours before Nixon resigned. “Annie always manages to get something telling in a portrait without props, without anything but the person himself,” says former Rolling Stone art director Mike Salisbury, “and that’s the hardest thing to do in photography.”

Paradoxically, the shy Leibovitz specializes in subtly baring the egos of subjects like underground-film star Joe Dallesandro and rock star Keith Richard. “I try to bare myself to a person so they can see I’m a human being,” says Leibovitz. “Mailer asked me if I had read any of his books, and I said no. He said, ‘Oh, that’s OK. No one really reads my books’.” Mailer scheduled her for a one-hour session, but she hauled her sleeping bag over to his porch and became a member of his household for several days. Her femininity can be an asset. “Men will often show a softer side of themselves to me than if I was a male photographer they might go out and get drunk with,” she says.

Leibovitz grew up with five brothers and sisters on military bases where her father was an Air Force colonel. Her mother used to dance with Martha Graham. After studying painting for a year at the San Francisco Art Institute, she bought her first camera while visiting her parents in Japan and learned to develop prints in the base hobby shop. She spent her junior year in Israel living in – and photographing – a kibbutz and working on an archeological dig that turned out to be Solomon’s Temple. In her senior year she spent most of her time in the school’s darkroom. One day her boyfriend, a San Francisco photographer, drove her to the Rolling Stone offices with her picture of Ginsberg. The editors loved it.

Freaky: Rolling Stone put her on a retainer — $47 a week. While she finished school she built a reputation shooting rock-and-roll stars like Rod Stewart and Grace Slick – pictures that more than any others captured the young, rich, freaky stars of the world of pop. In 1971 she begged Rolling Stone’s boy-wonder editor, Jann Wenner, to let her shoot her now-famous pictures of John Lennon while Wenner interviews the ex-Beatle. “I flew youth fare, stayed with friends, took the subway and turned in an expense account of $25,” says Leibovitz. Today she rarely turns in expense accounts and regularly loses her cameras. But she now retains ownership of her negatives and has a “love-hate” relationship with Wenner, whose wife, Janie, is her closest friend. “Rolling Stone is my vehicle, my license for shooting these people,” says Leibovitz. “It’s reallly a luxury liner to be traveling on.”

Leibovitz approaches her work with an artist’s eye, and she refuses to compromise. “I’m constantly framing my shots like a continuous movie,” she says. “A lot of times my best pictures can’t be used for the cover of the magazine because I haven’t left room for the logo.” Leibovitz treats cameras as tools. “People who talk about their equipment all the time bore me to death,” she says. For her a good photograph traps the body for that split second when it becomes one with the character. “I’m very aware of bodies,” she says. “The only time I forget my own is when I’m taking pictures. Then I float.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.