Original Publication: Women’s Wear Daily, September 18, 1975

Naples – Two Mafiosi hired for the occasion are stand guard outside the old Neapolitan tenements “just in case.” Inside the inner courtyard a film crew is setting up amid chaos. Half the neighborhood is working as extras. The other half – furious at not being “discovered” – hangs out windows and sings arias. When all else fails, they scream.

Suddenly a car pulls up and out jumps a tiny, taunt figure in rose-colored jeans and campy white plastic framed glasses. She rushes past the guards, takes one look at the scene and immediately picks up an electric bullhorn. “Silenzio!” she yells. “You idiots are driving me crazy.”

Her curses, delivered in two dialects, are creative enough to silence even the Neapolitans. Next she fixes her attention on the wet laundry suspended from bamboo poles across the courtyard. “Tell the signora to take in her wash,” she snaps to one of her three female assistants. “They didn’t have flowered sheets in 1938.”

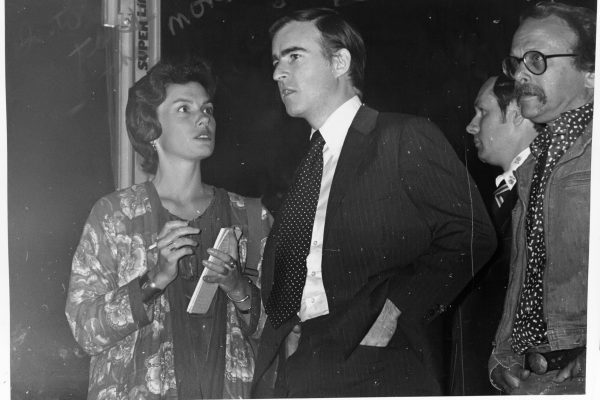

Lina Wertmuller, the world’s foremost female film director, is making her usual nonchalant entrance on the set of her sixth feature film, “Pasqualino Settebellezze” (“Pasqualino Sevenbeauties”). Today, Ms. Wertmuller, 47 – a Roman by birth whose great-great grandfather was a Swiss nobleman named Wertmuller Von Elgg – is not only one of Italy’s top money-making directors but is also one of the two or three women in the world able to direct films with multimillion-dollar budgets.

Until recently, however, she was almost unknown outside of Italy. Then, last year, she made a big splash on the American film scene with her visually haunting and politically mature “Love and Anarchy” – the story of a highly principled young man in a ‘30s bordello – and “The Seduction of Mimi,” a spoof of Sicilian machismo. In America the two films established Lina Wertmuller as a fully developed screen artist full of passion and wit. In Italy the same films already had proved that she could appeal to the highbrows and the masses at the same time.

In the process, she also managed to launch Giancarlo Giannini and Mariangela Melato, stars of “The Seduction of Mimi,” into Italy’s most popular and dynamic movie duo. This year her latest film, “Swept Away by an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Sea of August” – a more frankly commercial venture also starring Giannini and Melato and just released in the United States – is one of Italy’s top three money-making films for 1975.

Now Ms. Wertmuller is braving the drama and disorganization of Naples to make “Pasqualino” – the true story of a young Neapolitan in World War II who kills his sister’s pimp for honor’s sake and winds up in a German concentration camp. In a typical Wertmuller twist, Pasqualino’s only hope for survival is to make love to the 200-pound Nazi matron of the camp.

As in all her films, Ms. Wertmuller has written the script herself, and she has cast the kind of offbeat characters she learned to love when working with her film mentor, Federico Fellini. Her star is once again Giancarlo Giannini, and the films striking sets and costumes are by her visual mentor, her husband, Enrico Job, who also did the sets for Andy Warhol’s “Dracula” and “Frankenstein.”

“You know, when I direct,” Ms. Wertmuller laughs in throaty Romanesque, “I feel like a fencer with a broker sword balanced on the edge of a trampoline. I fight everyone.” Waving her beringed hands toard the Bay of Naples, she jokes, “I will leave my blood here.”

Her crew already feels somewhat bloodied. On the set she pushes everyone to give twice their normal effort. Her artistic control is total, and her crew lives in dread of what she’ll dream up next. But prop man Raffaele wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I like working with Lina,” he says, “because she’s the kind of person who, while she’s beating you to death, manages to convince you that it’s really you who are killing her.”

Each morning Ms. Wertmuller appears on the set keeping her plans for the day secret until the last possible moment. Then, with the agility of someone half her age, she hangs over rooftops checking camera angles. She lies on her back pointing a hand-held camera behind her. She orders a drainpipe removed from the side of a building and then holds the technicians by their belts while they execute her order. She choreographs every step her actors take and sits crosslegged under the camera lens feeding them their dialog. (Italian movies are all dubbed later, so it doesn’t matter how much noise the director makes during a take.) She pinches one actress’ bottom to get the desired reaction and has Giannini play closeups of his love scenes to her instead of to his leading lady.

Before shooting even began on “Pasqualino,” Ms. Wertmuller spent 10 days rehearsing leading actress Elena Flore, who neither reads nor writes, in a song-and-dance routine. She also spent months poring through thousands of photographs of bit players and sent her assistants to comb the back alleys of Naples for just the right faces.

She is also concerned with letting her characters speak in Italian dialects. “Love and Anarchy” featured 20 dialects. “My films speak the way the masses speak,” says Ms. Wertmuller. “Cinema is the most popular art, so it is very important to dedicate my films to the masses because they are the future of the world. If the masses don’t hurry up and understand the world’s problems, then we will all end and probably badly.”

Ms. Wertmuller herself was never a part of the masses. The daughter of a prosperous Roman lawyer, she followed her father’s wishes by studying to be a teacher, but she also enrolled secretly in Rome’s Academy of Dramatic Art with her best friend, Flora Carabella, who later married Marcello Mastroianni. While still in her 20s, she began writing, directing and serving a long apprenticeship of two of Italy’s leading musical comedy writer directors.

Then, itching to get closer to film, she began as Fellini’s assistant on “8 ½” but soon got bored and shot a documentary on the making of the film instead. When “8 ½” was finished, she coaxed Fellini’s camera crew to the south of Italy. With almost no money and a handful of women friends – mostly wives of men big in the Italian movie industry – she made her first film, “The Lizards.” The award-winning film detailed the stagnation of life in a small provincial town. Many of her close friends still feel it is her most beautiful film.

While she was in her 30s she met her husband, who is several years younger than she. They fell madly in love the first night they met and have been together, personally and professionally, ever since. “Enrico is very important to me in my work because he’s such a demanding and precise artist,” she says. “It is very important in film to create worlds and spaces. He is fantastic in both.”

Ms. Wertmuller’s films have been praised for their feminist sensibility and knocked for their lack of it. “I am surprised that everyone remarks about my sex,” she says.

“I think of myself as a person. Of course, being a woman is a factor, but there are so many factors and they can all be overcome by work. Women have these complexes about being women – more in America than in Italy. American women think they’re advanced because they’ve worked for so many years, but they mostly work as secretaries.”

Ms. Wertmuller’s strongest impression of American women came on her trip last winter to the United States, when she saw the documentary on China made by Claudia Weill and Shirley MacLaine, “The Other Half of the Sky.” “All these American women of different social classes seemed to see in China.” Ms. Wertmuller says, “were nurseries and how children were born. They created a ‘women’s look’ to the film. I wanted to know about the political and social structure of China – how factories are run, how cars are built, what Mao thinks. That film shows that the first racism is born in the minds of the women. They think of themselves as niggers.”

Lina Wertmuller, of course, is not saddled with such ladylike inhibitions. When some member of her film crew teasingly referred to another women on the set as a “ballbreaker,” Ms. Wertmuller shushed him immediately. “Just remember,” she said, “I’M the ballbreaker around here.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments