Original Publication: California Living Magazine – May 7, 1972

Early one recent morning I received an indignant phone call. It was my mother. “Why aren’t you over here? Arthur’s been here for hours. He’s got a new set of teeth, so he’s talking a lot. I’ve been trying to take notes for you.”

“What’s the story?” I mumbled sleepily.

“What’s the story! How many 111-year old men do you know who ride a bicycle? He’s beautiful. Hurry over here.”

About an hour later I arrived to find Arthur Reed seated at the kitchen table trying to eat a bowl of soup and some fried chicken while being quizzed mercilessly by my mother. She had snagged him on his way to a neighbor’s house where he was going to spend the day clearing a hillside of poison oak.

“Arthur was born in the South in 1860,” Mother said, waving her notebook triumphantly. “He ran away when he was nine and was raised by a white minister in Buffalo. I bet you don’t know why the Civil War started.” I was beginning to wonder if I should have stayed in bed. “I tell it like it is,” Arthur Reed said, clearing his throat. “the South was gettin’ rich because they got their work for nothin’. The rich white man, he had two wives, one white and one black, one in the bedroom and one in the kitchen, but he sold his own son. That’s why the North got mad.”

“Tell her, Arthur, tell her, what a big shot was.” Arthur obliged. “When a woman had a cook stove, a cow calf and a sewin’ machine she was a big shot. In them days men was the boss. Now women’s the boss. That’s why we have such bad trouble. That’s why the world’s messed up.” I was contemplating bringing up the question of male chauvinism with Arthur Reed, but at 111 I figured he was entitled to his opinions. Besides, Arthur wasn’t finished. “If the woman don’t like you, then she sues. But the lawyer, he takes everything. He breaks the both of you.”

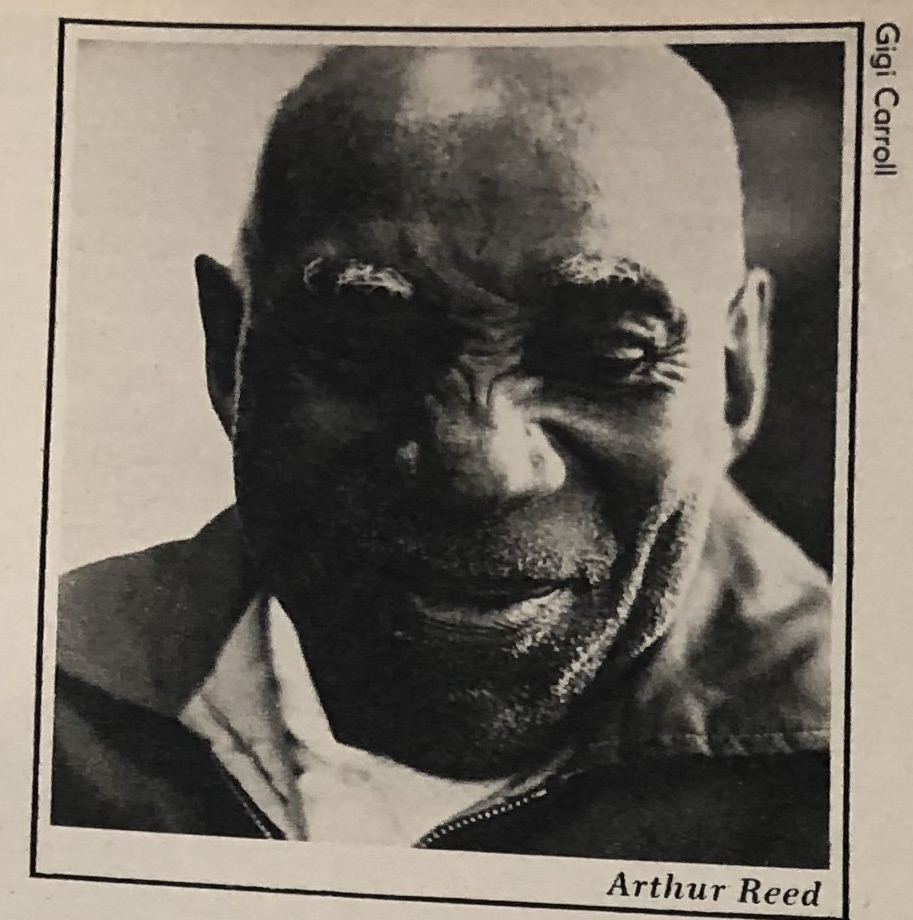

Arthur Reed barely looks seventy-five, certainly not old enough to celebrate his 112th birthday in June. His handshake is firm and vigorous, his tall lanky frame ramrod straight.

His hand are enormous and his most extraordinary feature. They looked 112, worn from a century’s worth of hard labor. His eyes are clouded with cataracts, but he acts as though they don’t exist. “I can tell the difference between men, women, and money. That’s enough.”

According to the 1970 census there are surprisingly, 10,607 people living in California over the age of 100, plus millions more trying to get there by popping vitamin E or seeking a guru. Arthur Reed’s prescription for survival is simple: A steady diet of Coke and candy bars, thanking God every day “I’m made out of such good dirt,” and no smoking or drinking. “The last time I got drunk was eighty-two years ago on eggnog. I never did go back to liquor. Once someone, some place or something bothers me, I never go back to it again.” He gets plenty of exercise by heavy gardening or unloading gondolas filled with pig iron at the Phoenix Ironworks in Oakland where he’s been employed off and on since 1928. He no longer unloads fifty-ton carloads of ingots by himself as he did when he was in his nineties, when he would challenge any man in the yard to beat him, but he’s still good for hundreds of pounds.

In fact, Arthur Reed enjoys working so much he lost his welfare. The Alameda County welfare department early this year discovered he was employed temporarily as a watchman at the Ironworks and failed to report it. So they took away his welfare checks for six months but decided against jailing him because of his age. The welfare people probably figure they have enough image problems without locking up 111-year-old men. Arthur accepted the loss philosophically – he now works for “gifts only.”

“I’m real neat and precise like. If I don’t work for two or three weeks I get into trouble. I just can’t stand sittin’ home with nothin’ to do. It bothers my arthritis and it bothers my head.”

Until he was over 100 Arthur Reed spent the harvest season in the valley picking cantaloupes and scrub cotton.

At ninety-eight he farmed his ten acres of cotton in Fresno, regularly biking to Fresno from San Francisco, and was just about to bicycle all the way to New York when he suffered an attack of appendicitis and was forced to quit.

Arthur Reed’s been roaming the country working his way from state to state since he was nine when he first ran away from the South, a place he doesn’t like to talk about much. He remembers being whipped twice by white men, “but never after I was a man. The last forty-five years white people’ve been good to me.”

“I never did want to go back to the South.” Arthur remembers being told a “big woman slave cost $2,000 and an itty bitty woman $200.” He also remembers when “all you could see of a woman was her hands, her feet and her face. Nowadays, a woman gets dressed up to go to bed. She wears a robe, a nightgown and a head rag, but she goes half-naked down the street. It’s plumb disgustin’. I hate to see it.” Then he wrinkles up his nose and laughs, “It’s a pity, but men like it.”

Arthur’s had three wives but didn’t get married the first time until he was fifty. The second time, he was in his eighties, when he married a woman of twenty-nine with five children. He’s lived with his present wife, now seventy-three, for nineteen years.

He remembers America as a country filled with wooden sidewalks and wooden bridges, houses where cornbread was cooked in ashes, where children trudged barefoot through the mud five or six miles to go to school. Arthur Reed never went to school – never learned to read or write, but knows much of the Bible by heart and thinks hard about the fate of black people and what’s wrong with the younger generation.

“Schools today can’t wump the kids. You gotta wump ‘em to make them learn. Kids today are livin’ too fast. They go to jail when they’re twelve or fourteen years old. In my day, if a kid don’t behave hisself you take ‘em out behind the wagon. After that they behave.”

“We gotta help kids find jobs. People gotta help one another. White man started out takin’ everything and the black man got nothin’ ‘cept the cold hard chill. Ain’t nobody done as good as the black man since the Civil War. We got educated black people, rich black people but they got their money in the white man’s bank and won’t help the others. We don’t need no million dollar churches to go to hell or heaven. We could take that money and put it into factories or farms so people can help themselves.”

Arthur is deeply religious and preaches his ideas at his church where he’s a deacon, and in his spare time he never stops planning for his own future. At 111 he wants to be set up in business, to own a junk store or go around the country giving speeches on his ideas of black capitalism and what it’s like to live to be almost 112. But not for free. Arthur wants to charge admission. “Last time a reporter talked to me I didn’t get nothin – not even a free paper. Years ago they paid me ninety cents an hour to preach so I preached twelve hours. I’d train what to say – it’d be worth thousands of dollars. I want the mayor of the town and the governor of the state to see me – it’d be worth money to them.”

Then Arthur Reed gets up, ready to work as he has for the last hundred years. “Remember, if you make a fortune off this story you better cut me in.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments