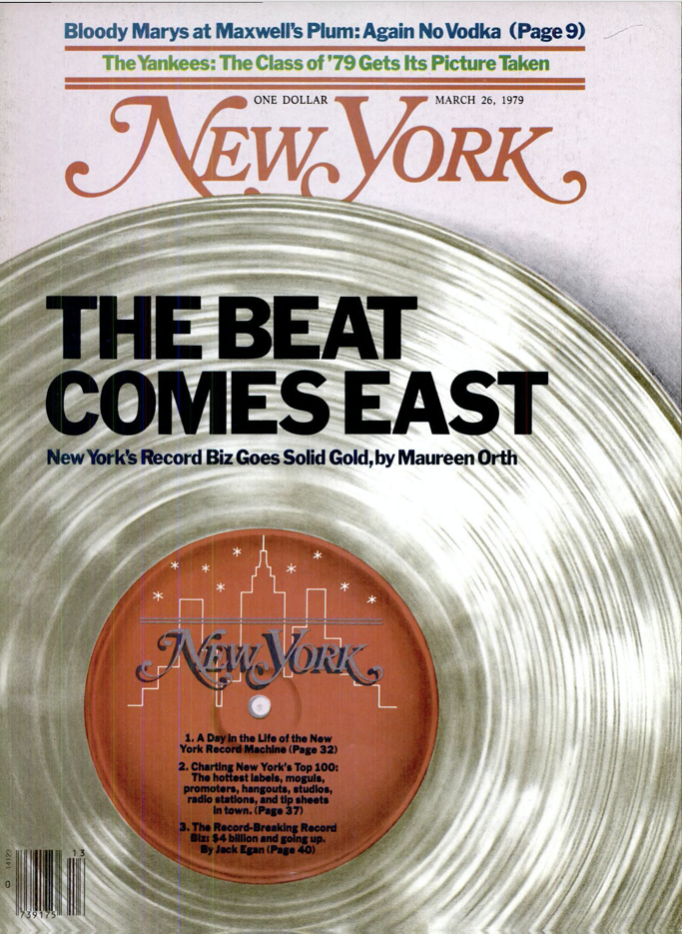

Original Publication: New York Magazine – March 26, 1979

Take a night, any night, right now in Manhattan. Kiss is rehearsing. David Bowie, James Taylor, and Carly Simon are recording. So is Marvin Hamlisch and the cast of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd. Gilda Radner’s LP is getting its final mix, and Sly Stone’s hits are being disco-ized. Pick a recording studio—Electric Lady, Secret Sound, the Hit Factory, the Record Plant—business is booming at $200 an hour.

At Mediasound, a former Baptist church on West 57th Street, Engelbert Humperdinck and Paul Anka are waxing mellow while Kool & the Gang funk with rhythm and blues and Talking Heads are recording new-wave rock ‘n’ roll. Not far away, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen of Steely Dan, America’s most polished rock band, are overdubbing songs they’ve composed since moving back to New York after seven years in Malibu. “When Walter and I left town in ’72 it was pretty grim,” says Fagen. “It’s not grim anymore. I moved into the Stanhope Hotel last summer and from my window I could watch steel-drum bands, Latin, salsa, and even bagpipe groups playing in front of the Met. Then I’d go outside for a walk and all the way down to 43rdStreet one tenor sax would fade into another. It’s nice to have music in the streets.”

Although you wouldn’t know it from reading the city’s three newspapers, which cover the occasional payola scandal but not the industry, New York’s record business is an enormously rich and powerful one, now giving L.A a run for its billions in the vinyl sweepstakes. In the sixties the business and musical talent flew directly from London to California—Monterey pop and the San Francisco sound concentrated the bulk of the business in Los Angeles. “I remember when all the New York music lawyers were studying for the California bar,” says Allen Grubman, a top rock attorney. “The studio scene was so dead,” says Phil Ramone, now Paul Simon’s and Billy Joel’s producer, “that you had to subsist on jingles.” Later the action also moved to Detroit, Nashville, Philadelphia, and Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Now once again, as in the days of Tin Pan Alley and the days when Alan Freed introduced rock ‘n’ roll to many of today’s record executives at the Brooklyn Paramount, New York is hot.

Consider the following: Corporate headquarters for almost all of the largest record companies is New York. Disco started here and has not only electrified the city but is changing its image across the country. Radio stations in remote parts of Texas now offer free trips to New York to disco-contest winners so they can see disco at the Source. Disco has also opened up vast new worldwide markets for music made in New York; as the foreign market expands, New York is geographically more and more important. The once dormant club scene is vibrating with live music and energy.

“The energy’s definitely here,” says Michael Klenfner, a veteran record executive. “You walk through the halls of CBS, Arista, Atlantic here at 7 P.M. and everybody’s still working. Out in California at 4:30 they’re all gone. They give you the excuse ‘New York’s closed.’”

Some of the biggest names to break through to the mass audience in rock in the past two years are based in New York—Bruce Springsteen, Foreigner, Billy Joel, the Blues Brothers. Joni Mitchell has quit Bel Air for a loft in SoHo, and even Linda Ronstadt is looking for a New York apartment so she can spend as much time as possible here.

Taking a cue from Ms. Ronstadt’s California boyfriend, who has benefited hugely from the cash and cachet of rock ‘n’ roll, Manhattan Borough President Andrew Stein is attempting to do the same sort of red-tape cutting for the music business that City Hall has been doing for the movie industry. He recently gathered a committee of local record-industry figures to discuss everything from better accommodations for rock stars (who are often given third-rate rooms in first-class hotels because of the damage they wreak) to a pop-music museum and tax breaks for the music industry’s millionaires. The committee also wants the Grammys show brought back to New York.

Record-company scouts have followed the talent eastward. At Warner Bros., vice-president for talent acquisition, Bob Krasnow, has signed big-selling acts like Steely Dan and the Funkadelics. After 25 years in California, Krasnow has just bought a Fifth Avenue co-op. “There’s a renaissance going on,” he says. “The music business used to look at New York the way the financial community did—it was bankrupt. But that started changing a few years ago when San Francisco O.D.-ed on itself and L.A.—well, L.A. has never been a forerunner for music. It’s a gathering place. New York both starts and gathers.”

Of course the music business has its own peculiar style. It’s considered worse to be boring than to be dishonest. Despite constant rumors of impending government investigations into payola and mob influence in the industry, the music business remains unconcerned and refreshingly primitive—streetwise and still based largely on gut instinct. Herewith, a day in the life…

Susan Blond and Andy Schwartz are leaving the Museum of Modern Art after just having heard a cassette of new Epic artist Tonio K’s album, Life in the Foodchain. “La Blondita,” a former Warhol superstar, is the publicist for the album and head of publicity for CBS’s Epic label. “Tonio K loves Dada, so just come to the fur-teacup room,” she had said when inviting the music press to the first hearing. Blond has curly brown hair and a marvelously nasal voice and gives great lunch at “21.” Andy Schwartz is the balding 27-year-old editor and publisher of New York Rocker, a 20,000-circulation tabloid of haute punk and “alternative rock” that comes out every five or six weeks—“depending.” They are on their way to CBS headquarters down the block.

When they arrive at her office, Andy reaches into his navy-blue canvas bag and says, “Wait till you listen to this.” He pulls out a white vinyl 45 by the Dickies, a group of punks who recorded “Silent Night” on one side and Paul Simon’s “The Sounds of Silence” on the other, both at triple speed. “People like Andy give me the spark to go on,” says Blond, placing “Sounds of Silence” on her office stereo. It sounds absolutely horrendous, and Andy Schwartz loves it because that’s obviously what he thinks of Paul Simon.

Meanwhile, two floors down in Black Rock, Walter Yetnikoff, the powerful 45-year-old Brooklyn-born president of CBS/Records Group, is having his own problems with Simon. Yetnikoff presides over a section of CBS that will gross $1 billion this year. (The entire record industry turned over $3.5 billion last year; all the movies made was $2.6 billion.) Yetnikoff is crude and tough, part rabbi and part panther, but forthright enough to inspire trust from artists. It is clear he hates to lose. Simon has not renewed his contract with CBS and after fourteen years with the label is going to its arch rival, Warner Bros., for $13 million. Simon owes Columbia one more album, however. He started to record one, but not all the songs on it would be his own compositions. Yetnikoff let enough people know how furious he was that Simon felt justified in suing to get out of Columbia altogether. The chairman decided to play hardball—it will cost Simon and Warner $1.5 million to cover Simon’s remaining contractual obligation to CBS. Still pending is Simon’s suit for a proper accounting.

Yetnikoff, dressed in a conservative three-piece pin-striped suit set off by an open-collared violet silk shirt—an outfit that clearly demonstrates the dichotomy of his corporate and show-biz responsibilities—prowls around his office while his lawyers haggle with Simon’s lawyer. In other parts of show business, he says, “the burn-out factor is nowhere close to the record business. It’s much more competitive—there are many more records out there than TV shows or movies, and movie companies don’t have the success of record companies. A large part of my job is deal-making, but I also have a corporate responsibility. I can’t go hang out in clubs and then come back and make these big moneymaking decisions.” Would he have it any other way? “No. The most charismatic people in American culture emanate from the music business—it’s the most exciting part of American popular culture. My kids would much rather see the Eagles, or Bruce Springsteen, in a movie than Redford.”

A lawyer breaks in and talks to Yetnikoff, in code, about the negotiations over Simon. “Make him wait,” he says of Simon’s lawyer. “I don’t feel like settling with the little bastard today.” A few hours later the lawyers once again scurry in and out. The final contract of Yetnikoff’s newest prize is being worked out—Paul McCartney in the United States for $10 million. It is a definite coup. Not only is McCartney expected to do movie soundtracks, he may even write songs for Ringo, on CBS’s sister label, Epic. John Eastman, McCartney’s lawyer, is asked why he came to CBS. “It’s simple,” says Eastman. “CBS is in New York and Warner Bros. is in California. I hate L.A.”

It is decided in Susan Blond’s office that Walter Yetnikoff should hear the Dickies’ version of “Sounds of Silence.” It will make him feel better about losing Paul Simon.

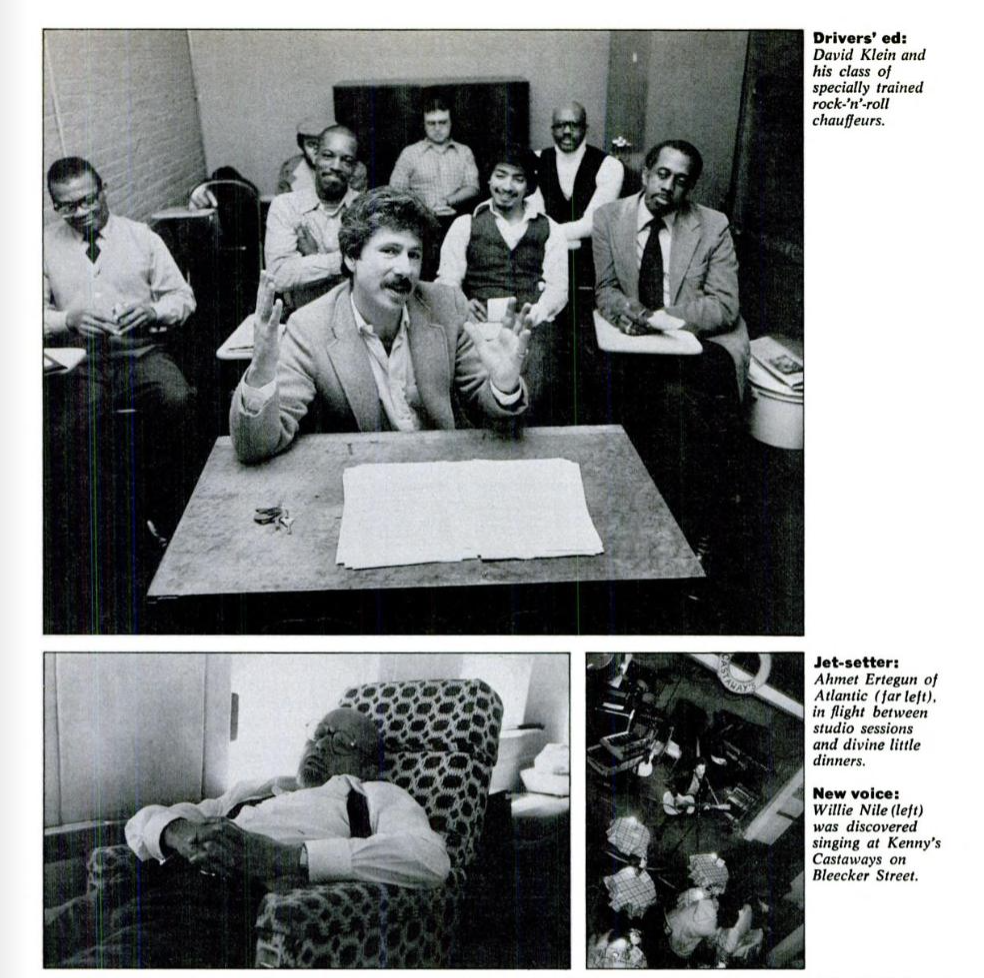

“All right, all right, does everybody know what a groupie is?” David Klein, of Dav-El Limousines, the limo service of Kiss and the Bee Gees, is conducting his school for rock-‘n’-roll chauffeurs. There are eight of them at the Dav-El garage on West 77th Street, and they are being indoctrinated into the world of the rock star as seen through the rearview mirror.

Klein, 33, began by parking cars as a teenager in New Rochelle. Today he owns a fleet of 55 limousines, including 29 custom-built Lincoln stretches—cars 44 inches longer than a regulation Lincoln, 36 inches in the center, and with the rear seat moved 8 inches back so his clients will never, never be seen when the stretch stops for a traffic light. The stretches cost $30,000 to build to Klein’s specifications, including custom-made stereo systems, and are stocked with liquor, organic fruit juices, Perrier, music-trade publications, and the latest in LP cassettes—provided free by record companies. They rent for $27 an hour, including tip, and business has doubled every year for the past five—a clear indication of how healthy the music business is in New York.

Klein gives his chauffeurs specific rules to follow:

- A rock concert is not your party. You belong outside.

- At times these rock people will become uptight and arrogant with you. Ignore it—it is nothing personal. These people were not brought up in limousines—it’s their treat, so understand and accept it. Do not let them abuse the car. I don’t care how famous a star is—if he has a fight with his girl friend and decided to put his foot through our stereo, you stop him.

- Don’t tell girls who your male clients are with. You never know when it can screw up a relationship.

- Never smoke a joint while driving.

- If a rock star wants to go to 117th and Lex to pick up dope, tell him to take a cab.

Because the Big Apple is home to the media and talent scouts, a certain kind of media mention can make an obscure singer’s career skyrocket. Look what happened to Willie Nile.

Willie Nile lives down in the Village. Last July when Willie, who’s 30, was playing at Kenny’s Castaways on Bleecker Street, the New York Times pop critic, Robert Palmer, there to cover somebody else, wrote a rave review, saying “he would seem to be the most gifted songwriter to emerge from the New York folk scene in some while.” The next time he played at Kenny’s, a dozen record scouts were in the audience, and a dozen offers for recording contracts followed. He signed with Arista.

It is 2:47 P.M. and a deliveryman knocks on Judy Weinstein’s door. He delivers four cartons of 50 records each of “Rock Your Baby” by the Force, “Do It” by Hilary, and “Hot for You” by Brainstorm.

Judy Weinstein runs For the Record, “New York’s No. 1 Disco Pool,” a nonprofit organization the top New York disco D.J.’s belong to in order to receive free disco records. She listens to eight hours of disco music a day, giving advice on disco picks to various tout sheets. “We are the trendsetters in disco music,” says Judy. “I heard 80 percent of all disco products is sold in New York.”

At 2:59 P.M., another deliveryman enters. He delivers twenty cartons of 25 records each from Atlantic.

In front of Judy in the large room on West 22nd Street, seven disco D.J.’s pore over the scores of new releases they’ve been flooded with this week. But before they can leave they must fill out a report on their last week’s booty. “My feedback system is the talk of the town,” she says. On a scale of zero to five the jocks have to rate the songs according to their opinions and what response they got in their clubs.

It is 3:10. The deliveryman unloads eight cartons of records from TK Records. He is followed by a man hauling four cartons from MCA.

“After about the twentieth new record, I can’t hear anything anymore,” says Wayne Scott, D.J. at the Cockring on Christopher Street.

At 3:22 P.M., RCA weighs in with eight cartons, including a reissue of “There but for the Grace of God Go I,” by Machine. The original had contained the line “No blacks, no Jews, no gays.” It’s been replaced by “Where the upper-class people live.”

“It’s chaos,” says Wayne Scott. “You know you can’t throw too much new stuff at the crowd in the club—they get mixed up and sometimes you miss a good record.” The phone rings. “That was the Black Music Association,” Judy announces. “They’re forming a committee on how to keep the R-and-B artist alive in spite of disco.” Then, voicing the most paranoid fears of 95 percent of the industry not connected with disco, she says, “Pretty soon, though, it’s all going to merge—rhythm and blues, Euro disco, pop, country-western—it’s all going to merge into disco with R-and-B overtones.”

At 4 P.M., JDC Records has sent three cartons. That makes 2,000 records delivered in just over an hour. “Sister Sledge has a song called ‘Lost in Music,’” says Judy. “That’s how I feel.”

Ahmet and Mica Ertegun’s townhouse was dripping with chic—they were giving a divine little dinner party for 30 or so. At just one table sat Jerome Robbins, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, Mike Nichols, Oscar de la Renta, Geraldine Stutz, Aileen Mehle (Suzy), and Mica, Ahmet’s interior decorator wife.

Across the room one could see Bill Blass, Dick Cavett, Cy Coleman, and Lady Slim Keith. No one in the music business can come close to Ahmet, the co-founder and chairman of Atlantic Records, when it comes to getting down with the BP. Ding-ding-ding went Ahmet’s knife on his wine goblet. “I invite you all upstairs to hear a new singer who I think is very special,” he said. “She’s only going to sing one or two songs.” Her name was Laura Brannigan.

Upstairs, Brannigan’s manager, Sid Bernstein, was pacing around very nervously. The guests assembled, and Laura Brannigan was introduced to the toughest audience in the world. She’s a tall, pretty woman, and her sexy, Broadway-show voice veered all the way from Barbra Streisand to Grace Jones. Naughty Sam Spiegel whispered that she sounded like a tinny electric heater. The applause was polite, and Cy Coleman took over at the piano immediately afterward.

Two days later in his office at Rockefeller Center, Ahmet explained, “I’m trying to do with her what I did with Bette Midler and Cher so that she has a certain…uh, you know, personality, before her first record comes out. Most people in the record business sign a singer and take her to a jukebox manufacturer’s convention in a pair of leotards. Maybe Oscar will dress her. I’ll call Alex Liberman to see if she can get into Vogue, Maybe you’ll write a story about her.”

That very day Suzy wrote: “Ahmet Ertegun, one of the great names in the music industry, thinks he has found a star of the stature of Barbra Streisand in young Laura Brannigan, whom someone describes as looking like Gary Cooper’s daughter Maria Janis if Maria were late for dinner. (You’ll have to figure that one out for yourselves.) Laura Brannigan has a remarkable voice, breathy and sexy and brassy all at once, and maybe Ahmet has discovered a comet.”

As a result of Suzy’s column, Look is planning a long piece, and three record producers called, wanting to cut her album. “Oscar” is designing her image—“healthy and attractive; she’s not a jive sexy girl,” says Ahmet. He is getting up a few more evenings. (“I think Nureyev will be at the next one.”) Once again the New York record-biz machine is in full gear, and anything can happen.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.