Original Publication – Newsweek: November 20, 1972

Fresh from his capture of all the Broadway prizes last season, Joe Papp, the innovative impresario of New York’s Public Theater, has set out on a new campaign – to tackle the mass audience and revitalize drama on TV. Currently he is hard at work producing the first two plays of an $8 million deal with CBS: his Shakespeare-in-the-Park production of “Much Ado About Nothing” and the Tony award-winning play by David Rabe, “Sticks and Bones.”

In each of the next four years, Papp, whose contract is the largest CBS has ever signed for theatrical specials, will produce from two to fives plays (including at least one Shakespearean production) for the network. CBS retains the option to air them and Papp has full artistic control. The average budget will be $600,000, although “Much Ado About Nothing” might go as high as $800,000, making it one of the most lavish productions ever staged for television.

Despite the hefty costs, CBS is banking on Papp’s original brand of drama reaping both prestige and commercial success. “The problem of TV drama,” asserts Fred Silverman, vice president of programming at CBS, “is that it’s been like musical chairs – the same creators year in and year out doing the same thing. Papp always ends up doing what nobody expects. The medium can use new vitality.

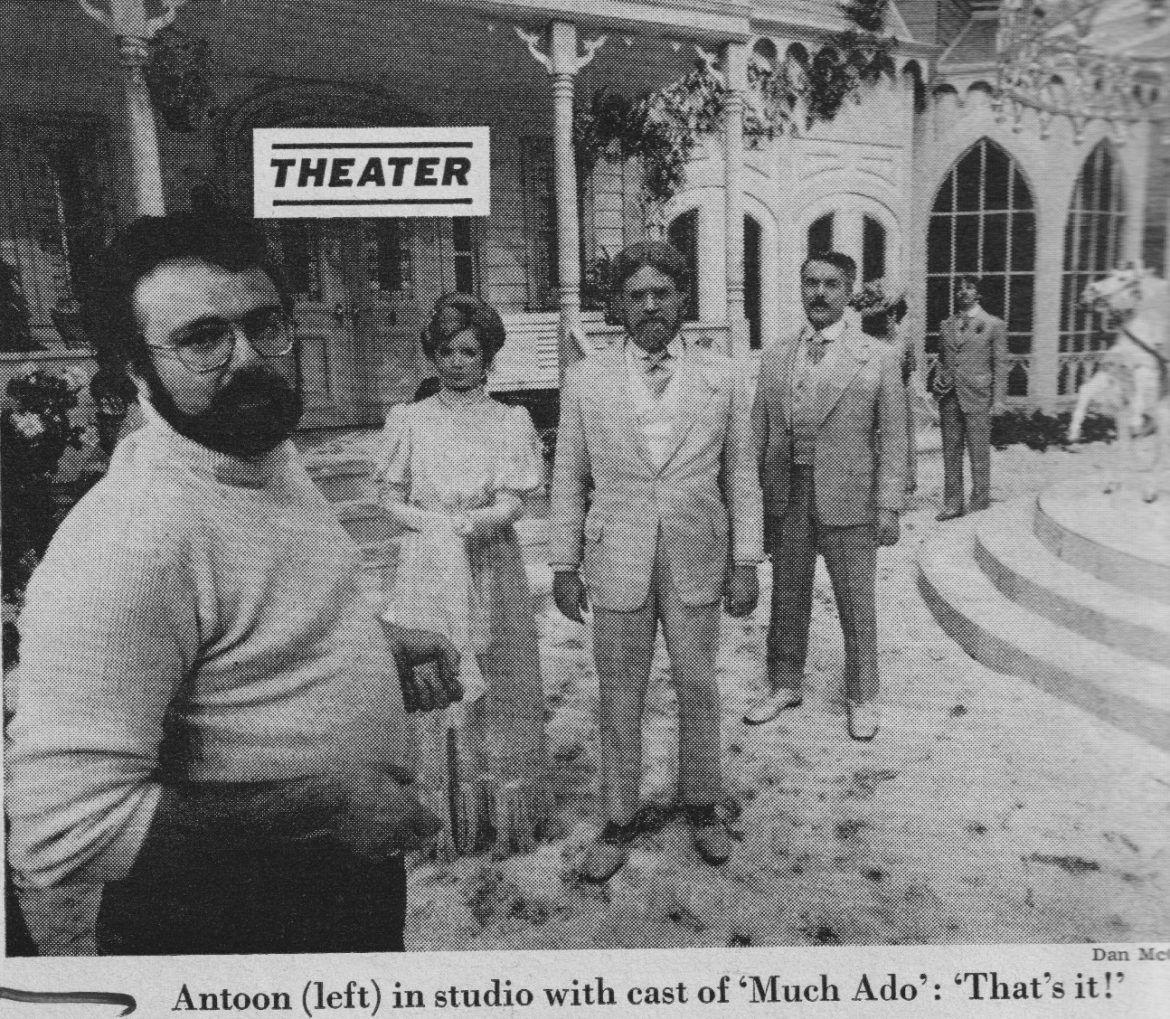

If anyone can provide that vitality, it is the dynamic young talent that Papp has assembled at the Public Theater, such as A.J. Antoon, the gifted 27-year-old theater director of “That Championship Season” and “Much Ado.” “I hated doing TV the first two days,” confessed Antoon. “I didn’t know what I was doing. Then on the third day,” said the former Jesuit seminarian, “a mystical experience happened.” Watching a love scene in the control booth, Antoon saw something on his monitor. “I started screaming ‘That’s it! I’ve got to have it! That’s the opening shot!’ From then on they understood what I wanted.”

On his side, Emmy award-winning cameraman Al Camoin, who worked with Arthur Penn and Paddy Chayefsky in the ‘50s “golden age” of TV drama, thinks that “these are the best-prepared actors I’ve ever workd with. We’re all giving maximum energy because we want to do more drama. The viewer at home needs more sophisticated scripts. This Shakespeare will appeal to adults we thought we’d lost.” It certainly appealed to one technician, who told the assistant producer after the love scene, “It makes me feel horny to watch it.”

CBS had a censor present to audit horniness; he objected that leading lady Kathleen Widdoes doesn’t shave under her arms and questioned the size of a “respectable bulge” for the men in a bathing scene. “I recognize the responsibility of bringing something into the home,” says Papp. “I’d never have excess violence and fake sexuality. But the fake way sex is usually portrayed on TV is diretier than showing it overtly. TV doesn’t show real relationships between people. I don’t believe the relationship between Edith and Archie Bunker.”

Irony: Years ago CBS would have bridled at such outspoken views. In 1958, because he refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, the same network fired Papp from his stage manager’s job. “Hardly anyone around now was here then,” shrugs the 35-year-old Silverman, who calls Papp “a genius, a total professional in every sense of the word.” Even so, the meetings between Papp and CBS had, says Bernard Gersten, Papp’s close associate and No. 2 man at the Public Theater, “a certai irony.” But the hard-nosed Papp is willing to forget the past. “If you know what a TV corporation is,” he says, “you’re never disappointed in what they do.”

To direct the TV version of “Sticks and Bones,” the surreal tragicomedy of a blind Vietnam veteran’s return home to his family. Papp, with characteristic daring, chose Robert Downey, the creator of freaked-out movie comedies such as “Putney Swope” and “Greaser’s Palace.” The 34-year-old Downey, one of the few original movie satirists, has never had a big commercial success and is frankly astonished that he’s directing on TV. “I see Rabe’s play as a nightmare with the Marx Brothers,” he says. “The funnier it is on the surface, the more horrible you’ll feel underneath.”

Blend: His selection of Downey underscores Papp’s desire to avoid the conventional. “There’s almost a formula with most TV, a formula of cuts and pace,” he says. “I can watch a show and usually predict every cut. I don’t want that.” ‘Much Ado” is being shot directly on videotape; Papp’s aim is to get a blend of Shakespeare’s language and the atmosphere of turn-of-the-century America. For “Sticks and Bones” Downey will shoot on tape, then convert it to 16-mm. film so that he can edit it on a Movieola, then put it back on tape.

For Papp, going on television is a logical extension of his Public Theater. “I’ve always been interested in the mass audience,” he told NEWSWEEK’s Maureen Orth. “I like their contradicitions, their narrow-mindedness, their suspicion about certain things. For us, TV is a way to reach that audience. We want to break down the barriers between live theater and the mass media of television and film. Hopefully, this will increase live theater by huge percentages.”

Hopefully. In any case, despite made-for-TV movie specials like “Brian’s Song” and occasionally filmed plays on the Public Broadcasting Service, American mainstream television is starved for good drama. “Do you realize,” points out Papp, “that the British program more than 700 hours of drama a year on TV?” Even the so-called golden age of TV drama back in the ‘50s, with its work by writers like Gore Vidal, Stirling Silliphant and Robert Alan Aurthur, was only golden compared to the zinc of normal TV fare. If Papp succeeds in bringing together high quality and wide audience response, other networks are sure to follow CBS, and then U.S. television may have its first real golden age of theater-in-the-home.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.