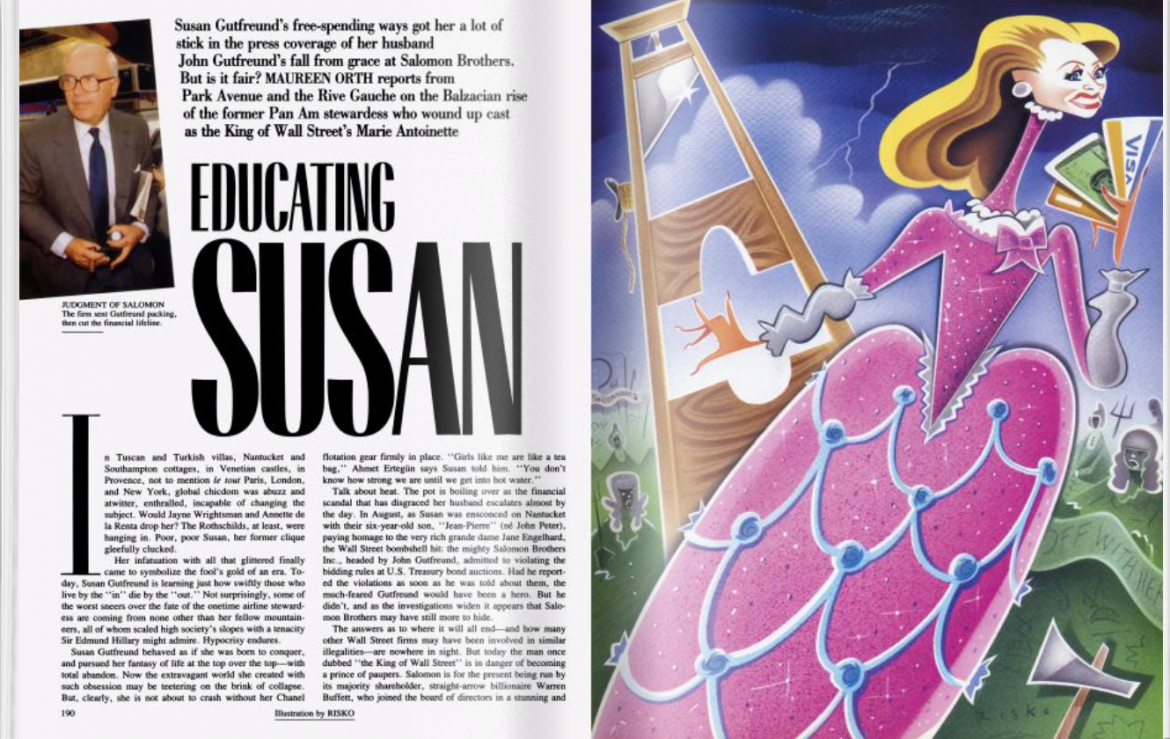

Susan Gutfreund’s free-spending ways got her a lot of stick in the press coverage of her husband John Gutfreund’s fall from grace at Salomon Brothers. But is it fair? MAUREEN ORTH reports from Park Avenue and the Rive Gauche on the Balzacian rise of the former Pan Am stewardess who wound up cast as the King of Wall Street’s Marie Antoinette

In Tuscan and Turkish villas, Nantucket and Southampton cottages, in Venetian castles, in Provence, not to mention le tout Paris, London, and New York, global chicdom was abuzz and atwitter, enthralled, incapable of changing the subject. Would Jayne Wrightsman and Annette de la Renta drop her? The Rothschilds, at least, were hanging in. Poor, poor Susan, her former clique gleefully clucked.

Her infatuation with all that glittered finally came to symbolize the fool’s gold of an era. Today, Susan Gutfreund is learning just how swiftly those who live by the “in” die by the “out.” Not surprisingly, some of the worst sneers over the fate of the onetime airline stewardess are coming from none other than her fellow mountaineers, all of whom scaled high society’s slopes with a tenacity Sir Edmund Hillary might admire. Hypocrisy endures.

Susan Gutfreund behaved as if she was born to conquer, and pursued her fantasy of life at the top over the top—with total abandon. Now the extravagant world she created with such obsession may be teetering on the brink of collapse. But, clearly, she is not about to crash without her Chanel flotation gear firmly in place. “Girls like me are like a tea bag,” Ahmet Ertegun says Susan told him. “You don’t know how strong we are until we get into hot water.”

Talk about heat. The pot is boiling over as the financial scandal that has disgraced her husband escalates almost by the day. In August, as Susan was ensconced on Nantucket with their six-year-old son, “Jean-Pierre” (né John Peter), paying homage to the very rich grande dame Jane Engelhard, the Wall Street bombshell hit: the mighty Salomon Brothers Inc., headed by John Gutfreund, admitted to violating the bidding rules at U.S. Treasury bond auctions. Had he reported the violations as soon as he was told about them, the much-feared Gutfreund would have been a hero. But he didn’t, and as the investigations widen it appears that Salomon Brothers may have still more to hide.

The answers as to where it will all end—and how many other Wall Street firms may have been involved in similar illegalities—are nowhere in sight. But today the man once dubbed “the King of Wall Street” is in danger of becoming a prince of paupers. Salomon is for the present being run by its majority shareholder, straight-arrow billionaire Warren Buffett, who joined the board of directors in a stunning and unprecedented move to cut Gutfreund off from help with his legal fees or any other perks. (Buffett himself reportedly now uses Gutfreund’s car and chauffeur.)

Gutfreund is currently a target of five civil and criminal investigations by everyone from New York’s U.S. attorney to the S.E.C. He is looking at years of testimony and depositions, shareholder suits, the possibility of jail time, and millions of dollars in legal fees out of his own pocket. Although Buffett called his behavior “inexplicable and inexcusable,” Gutfreund chose not to show remorse. His response was completely in character: according to The Wall Street Journal, he said, “Apologies don’t mean shit.”

Needless to say, her former allies wonder whether Susan Gutfreund can adapt as easily as the Trumps, who went shopping together recently at K mart, and Salomon traders have already organized a betting pool on which month Susan will file for divorce. No matter that it was the husband’s behavior that was called into question, it was at the wife that the gilded ones on both sides of the Atlantic aimed their barbs. They immediately unleashed a raft of Susan jokes, most of which play off her famed Francophilia, in evidence long before she learned to speak French properly.

“What did Susan say after John told her what had happened?”

“Mon Dieu! Quel desastre!”

Or: “It’s a ball-buster, n’est-ce pas?”

Or: “I never thought I’d see the day that John would embarrass Susan.”

They laid it on as lavishly as Susan had in her early nouveau period at River House in New York, when she served caviar as an appetizer, chili for the main course, and floating islands for dessert. They claimed that she couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about, that she insisted, “What John did is no worse than going sixty in a fifty-five-mile-per-hour zone.”

In some circles, it was even suggested that Susan Gutfreund’s hunger for luxury, her fabulous faux pas, her escape to Paris to hang out with the Rothschilds and the Agnellis after she was hounded out of New York by bad press, made her somehow responsible for her husband’s downfall—she distracted him and blew him off course. The merchant princes of Paris, however, where Susan is considered adorable and where wives remain more in the background in business, beg to differ. “John Gutfreund is a big boy,” asserts Baron Elie de Rothschild. “If I get in a mess, it’s my fault, not my wife’s. If I do something dishonest, I’ve made a horse’s ass of myself. If you’re the wife, you stick with him and say, ‘You’ve been a stupid ass.’ Now listen, madam,” the baron continues, warming to his subject, “if you marry a banker, normally one might say a wife is paid by her husband to give dinners for his clients.”

“Even if she behaved as millions of wives for millions of years have, to push their husbands to spend, to have a lavish time, it’s very indirect,” agrees Baron Elie’s cousin Baron Guy de Rothschild. “She might have had an influence one way or another, but that doesn’t mean she bears real responsibility.” So how did Gutfreund get into this mess? “I think it’s pride,” Baron Elie practically whispers. “You think you’re the king, that nobody can touch you—you can do whatever you want. It happened to Napoleon, it happened to a lot of big men. He thought he could get away with everything. He did what he thought he had to do. It had nothing to do with Susan.”

Indeed, it is too easy to view Hungarian-Spanish-descended Susan Kaposta Penn Gutfreund as a mere striver about to get hers. Her diligence, her devotion to elevation and to acquiring the knowledge of her betters, are simply too intense. “If some of these women didn’t care about style, they could run countries,” says one social observer. Those who know Susan best seem to divide between the offended, who consider her irredeemable, pretentious, and absurd, and the sympathetic, who see her as irrepressible, generous, and charming. The latter are only amused that she told a New York Times reporter she was born in England in a thatched cottage, perhaps not realizing that the reporter would also call her father and learn that he was a retired air-force pilot and that Susan, the only daughter in a family of five sons, was born in Chicago and raised “all over the place.” They smile when they hear that she informed someone who admired her embroidery-covered walls in New York, “Oh, I did that when I was at the convent boarding school.”

Her lack of formal education is really not the point. Susan Gutfreund comes right out of a great American tradition that harks back to Henry James and Edith Wharton. Past goddesses of self-invention like Wallis Simpson and Grace Kelly had, of course, a little polish to start with. But for these marvelous late-twentieth-century specimens, the driven and sexually experienced second wives who so recently took New York by storm, the less baggage the better.

“These women became,” says the nouvelle observatrice Barbara Howar. “They don’t have a background—only a beginning and an end.”

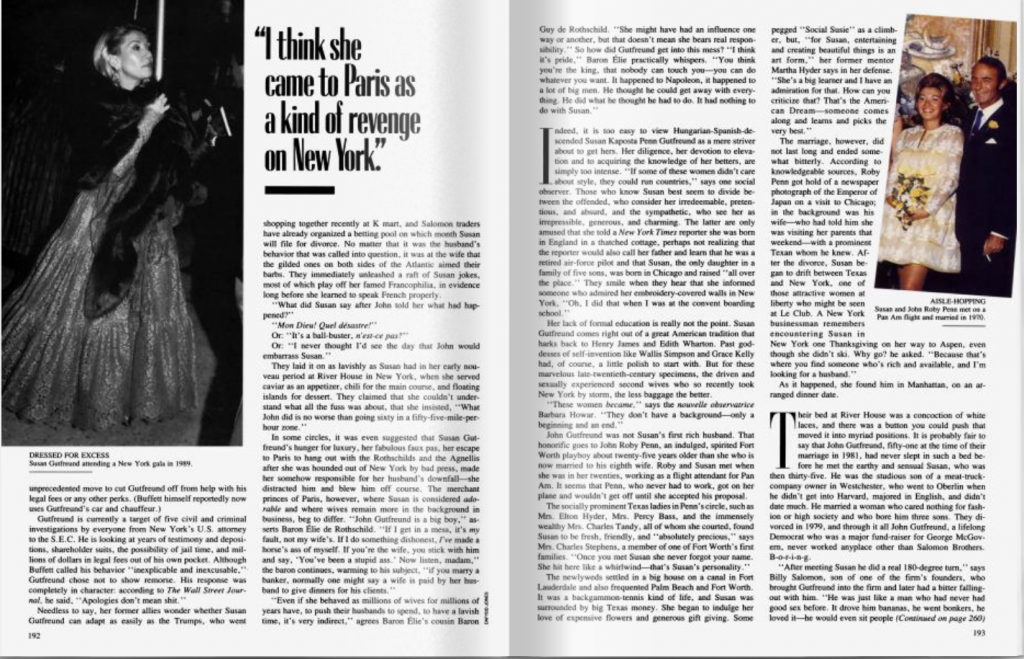

John Gutfreund was not Susan’s first rich husband. That honorific goes to John Roby Penn, an indulged, spirited Fort Worth playboy about twenty-five years older than she who is now married to his eighth wife. Roby and Susan met when she was in her twenties, working as a flight attendant for Pan Am. It seems that Penn, who never had to work, got on her plane and wouldn’t get off until she accepted his proposal.

The socially prominent Texas ladies in Penn’s circle, such as Mrs. Elton Hyder, Mrs. Percy Bass, and the immensely wealthy Mrs. Charles Tandy, all of whom she courted, found Susan to be fresh, friendly, and “absolutely precious,” says Mrs. Charles Stephens, a member of one of Fort Worth’s first families. “Once you met Susan she never forgot your name. She hit here like a whirlwind—that’s Susan’s personality.”

The newlyweds settled in a big house on a canal in Fort Lauderdale and also frequented Palm Beach and Fort Worth. It was a backgammon-tennis kind of life, and Susan was surrounded by big Texas money. She began to indulge her love of expensive flowers and generous gift giving. Some pegged “Social Susie” as a climber, but, “for Susan, entertaining and creating beautiful things is an art form,” her former mentor Martha Hyder says in her defense. “She’s a big learner and I have an admiration for that. How can you criticize that? That’s the American Dream—someone comes along and learns and picks the very best.”

The marriage, however, did not last long and ended somewhat bitterly. According to knowledgeable sources, Roby Penn got hold of a newspaper photograph of the Emperor of Japan on a visit to Chicago; in the background was his wife—who had told him she was visiting her parents that weekend—with a prominent Texan whom he knew. After the divorce, Susan began to drift between Texas and New York, one of those attractive women at liberty who might be seen at Le Club. A New York businessman remembers encountering Susan in New York one Thanksgiving on her way to Aspen, even though she didn’t ski. Why go? he asked. “Because that’s where you find someone who’s rich and available, and I’m looking for a husband.”

As it happened, she found him in Manhattan, on an arranged dinner date.

Their bed at River House was a concoction of white laces, and there was a button you could push that moved it into myriad positions. It is probably fair to say that John Gutfreund, fifty-one at the time of their marriage in 1981, had never slept in such a bed before he met the earthy and sensual Susan, who was then thirty-five. He was the studious son of a meat-truck-company owner in Westchester, who went to Oberlin when he didn’t get into Harvard, majored in English, and didn’t date much. He married a woman who cared nothing for fashion or high society and who bore him three sons. They divorced in 1979, and through it all John Gutfreund, a lifelong Democrat who was a major fund-raiser for George McGovern, never worked anyplace other than Salomon Brothers. B-o-r-i-n-g.

“After meeting Susan he did a real 180-degree turn,” says Billy Salomon, son of one of the firm’s founders, who brought Gutfreund into the firm and later had a bitter falling-out with him. “He was just like a man who had never had good sex before. It drove him bananas, he went bonkers, he loved it—he would even sit people down and tell them about it.” Salomon pronounces the fever a case of raging “male menopause.”

Susan not only made the former wallflower spend money, she got him to get up and boogie. They hired the socially correct decorators Mica Ertegun and Chessy Rayner; the Gutfreunds were invited to Thanksgiving in Barbados with the Erteguns and Jerry Zipkin and Lord Weidenfeld, who took it upon himself to explain to the bride the subtleties of when to say “house” and when to say “home.” The education of Susan was in full bloom, mostly in lavish displays of orchids, which became her signature. Susan, in fact, gave a whole new meaning to saying it with flowers—she would send $700 orchid trees just to decline a dinner invitation. In 1983 the Gutfreunds went as far as to rent Blenheim Palace, the Duke of Marlborough’s ancestral seat, for a Salomon ball—one entered the great hall to find a forest of green and a different flowering tree at each table. But all anybody seemed to talk about was the invitations: “Mr. and Mrs. John Gutfreund. At Home. Blenheim.”

Once they moved into River House in New York the Gutfreunds began throwing big parties and inviting top-drawer guests such as Annette Reed (now Mrs. Oscar de la Renta), whose mother, Jane Engelhard, owned a considerable block of stock in Salomon. Annette, godmother to the Gutfreunds’ child, once told the writer Michael Thomas that because of the family’s major financial interest in the firm, supporting Susan was a form of “flying the flag.”

In the early eighties, the banner of society in New York was being passed from those who exalted art and the avant-garde to a whole new crowd who doted on commerce—and what were parties for, anyway? Susan Gutfreund formed an alliance with social realtor Alice Mason and was thrilled to be friendly with Françoise de la Renta, Oscar’s late first wife, who had shrewdly recognized that these nouvelle party girls could be great for the dress business.

Susan’s most important role model, however, was the currently legendary Jayne Wrightsman, who came out from behind a perfume counter to marry her very rich and controlling late husband, made herself an authority on eighteenth-century furniture—endowing rooms at the Metropolitan Museum in the process— and secured a spot on the socialite All-Stars by helping Jackie Kennedy to refurbish the White House.

“I remember the Duke of Windsor telling Jayne, ‘We have lived with these things so long we don’t talk about them,’ ” says fellow traveler Rosemary Kanzler. Undaunted, the Wrightsmans bought other people’s taste and collections and shared their newfound knowledge in much the same way Jayne’s protégée later would—leading an art authority to say of Susan, “She copies copycats.”

Billy Salomon, for one, was dumbstruck by the transformation he observed in John Gutfreund, once so tight with a buck that he would complain if a partner spent $100 for dinner with an important client at “21.” Imagine the irony, then, when just a few years later Susan apologetically told their guest, the very chic international hostess Sao Schlumberger, that as it was Sunday night they would have to take her to dinner on—horrors— the West Side. And where did they pull up? Twenty-one West Fifty-second.

“I suppose some change began in 1979, after I got divorced,” Gutfreund told Institutional Investor in an interview earlier this year. “At that time so much of my life was extremely structured…. I had to be able to get to work and be ready to think every morning and operate throughout the day and sometimes into the early evening, focusing only on business and business problems…. Then I met Susan and married a couple of years after that. And because Susan was so different from my first wife and different from me, my horizons opened up.” Even so, Gutfreund maintained that high society was a bore. “The relationship seems to be mostly based on the idea that we’re all affluent. I think that’s ridiculous…. The social scene turned out to be exactly what I thought it was: frivolous.”

But if he claimed he couldn’t take it, she couldn’t seem to get enough, and she was used to having her way. After observing the Gutfreunds one New York evening when Susan implied coquettishly that her favors would be withheld if her husband failed to authorize the purchase of an expensive antique clock, Donald Trump quipped, “She’s doing surgery on his wallet.”

“She would tell him what to do, that he had no taste,” says one woman who spent a great deal of time with the couple. “John Gutfreund was terribly henpecked.”

The new Mrs. John Gutfreund’s diamonds were never as big as the Ritz, her only important painting was one of Monet’s water lilies—as the art snobs in Paris will tell you, he painted a lot of water lilies—and she hung it smack-dab in the foyer with orchid trees climbing alongside it. Nevertheless, Susan was making her mark, learning about decor and becoming a kind of homebound special-events producer. The jaded jet-setters who came to view Susan’s buffets, with spun-sugar fruits and birdcages made out of pasta, dismissed these painstakingly plotted affairs as the work of “a frustrated set designer.” But others appreciated all the trouble she took in an apartment that was ocean-liner-modem with little touches of eighteenth-century froufrou thrown in. “Susan never wanted to shock,” says her impeccable friend Deeda Blair. “She wanted to be noticed.” Mrs. Blair adds that Susan once told her that arranging an exquisite centerpiece was like “playing in a dollhouse.”

And Susan was always eager to share what she had learned. Barbara Howar recalls sitting with Barbara Walters at a New York dinner party one night when Susan wafted by and said, “If you all ever want to know anything about trompe l’oeil painting, I’d be happy to tell you.” Says Howar, “It was not intended to be funny.” Howar, impressed by her friend’s generosity and her full-tilt southern style, says Susan thought quite ingenuously that by marrying John Gutfreund, and all the institutional power that came with his being the chairman and C.E.O. of Salomon Brothers, she had been given a charge. “She thought that by landing him she had a carte blanche that allowed her to operate like nobody else. What she did she did well. She cared about John and made him happy.” She also “went overboard,” says Howar, “and whatever she did was all right with him.”

The Gutfreunds tried to keep up despite the fact that their $35 or $40 million was only a tenth of what some of those they socialized with were worth. Who could forget the lawsuit over Susan’s insistence on installing a winch on her neighbors’ roof at River House to hoist a twenty-two-foot Christmas tree up the side of the building and into her two-story apartment? Not to mention her practice of turning out the light above a door that led to the neighbors’ penthouse, apparently because she wanted everyone to think she lived on the top floor. This, combined with her habit of telling guests to “come to the penthouse,” led her alienated neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Robert Postel, more than once to encounter strangers, including designer Hubert de Givenchy, stepping off the elevator into their living room.

“We had a procession of masseurs, masseuses, piano tuners, someone delivering two thousand orchids for her ceiling,” Robert Postel says. But nothing quite compared with the two A.M. visitation by a group of formally dressed guests, one of them carrying a harp. Postel, clad only in his Jockey shorts, told them, “Sorry, it’s not my time to go.”

What becomes a legend most? Clearly not River House. By the time John Peter was born, in August of 1985, the Gutfreunds were already planning to move to grander quarters. Once the correct module was found for $6.2 million on Fifth Avenue, Jayne Wrightsman intervened. The job of decorating the Gutfreunds’ Gotham chateau would be undertaken for millions more by none other than the incomparable eighty-seven-year-old Henri Samuel of Paris, who would be brought out of retirement for the commission. He did not disappoint, and created a Louis-Louis habitat fit for a close personal friend of Marie Antoinette’s. Susan flew bands in from Paris for after-dinner entertainment in the winter garden, graced with an English porcelain fireplace. It was such fun to hop the Concorde to buy a $100,000 eighteenth-century Russian desk. The antiquaires loved her. In the words of one, “She became a great animatrice of the market.” Thus began the ici and la of Susan’s Parisian period.

“I think she came to Paris as a kind of revenge on New York—to punish New York, to get even,” says one French noblewoman. Flanked by the protective cachet of Wrightsman and Samuel—charter members of an exclusive petitParisian tribe of eighteenth-century passionists that also includes Karl Lagerfeld, Liliane de Rothschild, Hubert de Givenchy, and Princesse Laure de Beauvau Craon, director of Sotheby’s in Paris—Susan began to soak up the rites and cultural language and to set her sights way beyond those of Ivana, Gayfryd, and Carolyne. “Some friends asked if we could give a party for them,” Baron Elie de Rothschild recalls of Susan’s orchestrated entrance. “Of course, everybody knew Gutfreund in business, and Henri Samuel and Givenchy also gave parties.”

Although Gutfreund preferred New York to Paris, he supported his wife in her European pursuits. It wasn’t long before she coveted her own showplace, and Givenchy came to her aid, asking if she would care to purchase the former servants’ quarters of the elegant building he would also buy into on the Rue de Grenelle, in the Septieme Arrondissement near the French Assembly. Once again Henri Samuel was called in to supervise the decor. For her Parisian sojourns, Susan Concorded over frequently with child and nanny and installed herself in a $l,000-a-day suite at the Ritz. When at last her four-floor jewel, with its intime dining room and newly excavated ceramic-tiled garage equipped with car wash and fax, was completed she was ready to take on the City of Light.

Out came the monogrammed shopping bags—her merchant and floral sources are never revealed, so gifts are delivered bearing only her card—and the stories of her ingratiating extravagance began to make the rounds. Liliane and Elie de Rothschild heatedly deny that Susan gave the baroness letters written by Marie Antoinette worth around $14,000 and that Liliane returned them. Others, perhaps taken with the symbolic charm of such a story, insist it happened. Liliane, who did receive an elaborate eighteenth-century beaded bag once used by French noblemen for their gambling, says she considers Susan “like a daughter. She had lovely linens embroidered in Spain for me with my initials and lily of the valley. And years ago she gave me this paper, the Helmsley cipher.”

“The Helmsley cipher, madam?”

“For the choke.”

“The Heimlich maneuver?”

“Yes, yes. Thanks to that, it saved my life. I’ve put it up in all my children’s homes. I’m most grateful.”

For Baron Guy de Rothschild, who was fascinated by the works of Will Rogers, there were out-of-print editions for his collection; for Karl Lagerfeld, delicate, golden eighteenth-century scissors. This caused a minor uproar, since the gift of scissors means that friendship is cut,” but all I had to do was give her a coin back and it was finished,” Lagerfeld explains genially. Did he also give her free dresses? “Of course, as I cannot wear them myself.”

Many others were charmed by Susan’s passion for all things French. “During one lunch she gave us a little course in the eighteenth century and we listened—it was all so fresh to her,” says Princesse de Beauvau Craon of Sotheby’s. “It would fascinate people she had the fortitude to do so—she was exotic for Paris, something new. The bottom line, as the Americans love to say, is that they were a success.”

“Even the rich like to eat other people’s caviar,” adds a woman who runs one of Paris’s most exclusive salons. “She learned on the job. At the beginning her menus were more rich and flashy— she used to overdo a lot. But then the mixture of people became more interesting—I myself found the businesspeople interesting. Otherwise she was learning from all of us. I sometimes wondered why she wanted to learn that much; it amused me to see her develop, and I admired how quickly she learned.”

“Everything was done in a rather extraordinary way,” says Baroness Hélène de Ludinghausen, “and so people were interested or amused. Her success was that she became a character in her own way—she was very much onstage all the time and she made a point of collecting people who were glamorous.”

There was the 1988 party for sixty for Jayne Wrightsman—Susan, with the help of the celebrated party planner Pierre Celeyron, filled the first floor of Ledoyen restaurant with eighteenth-century antiques in order to re-create a period salon, while the tables were laden with silver-framed photos and books the guests had written. For John’s sixtieth birthday at the Musee Camavalet, the tableau was a recreation of an orangerie of Louis XV, exactly as described by the king for an outdoor fete, down to semicircular tables placed around a boxed orange tree banked with woven camellia leaves. That party took at least “two months and fifteen meetings” to plan, according to Celeyron. “She is very fussy, but she’s right.”

A year later Susan threw another big bash, at a chateau near Fontainebleau, Vaux-le-Vicomte, originally constructed by Louis XIV’s finance minister. (The locale would prove ludicrously portentous: when the king arrived to see such beauty he called his minister a crook and eventually threw him in jail.) Interestingly, Susan herself was feted by those much older than she. For her birthday last year the guests at the small lunch Liliane de Rothschild gave were mostly male and mostly over the age of eighty. At fifty-three, Karl Lagerfeld was the baby of the bunch.

But when the parties ended, the French always returned to the business at hand. “I have a feeling a lot of people the Gutfreunds saw here made a lot of money with him,” says Lagerfeld, echoing a sentiment heard again and again in Parisian society. “Yes, the Agnellis and the Niarchoses and the Livanoses—why not?”

Evidently, the Agnellis had only a vague idea of who the Gutfreunds were until Gianni Agnelli was hospitalized in New York in 1983 for coronary-bypass surgery. Suddenly, day after day, huge bouquets from Susan and John Gutfreund arrived at the hospital. Once the connection was made, she pursued the legendary playboy on two continents and he got big presents. Susan reportedly angered Jayne Wrightsman by canceling a couture fitting the night before, begging off by saying she had a toothache; the next morning she went antiquing with Agnelli instead. Tiens! Unfortunately for Susan, Jayne Wrightsman decided to visit one of the same antique dealers that morning and was told that she had only just missed her good friend Mme. Gutfreund. When Mrs. Wrightsman later inquired about her visit to the dentist, Susan gave her a blow-by-blow account.

That little histoire was immediately followed on the gossip circuit by the one about Givenchy’s longtime friend Philippe Venet not being able to attend one of Susan’s dinners—there was no room at the table, because Gianni was back in town. “Don’t worry,” John Gutfreund assured a couple of startled New Yorkers on Malcolm Forbes’s yacht as all three watched Susan carry on with Agnelli, “she does that here, but she comes home with me.”

One Parisian remembers a dinner with Gianni Agnelli and Susan: “Before the dinner Susan was so emotional, she was panting like a girl before her first big dance. And then when he got up to toast, as he went around the room, he also talked about her. For her that was the sublime moment, all that that could represent as refinement. She was so happy. Then I began to see that money for her was serving a way of life—it wasn’t just money for money’s sake.”

“Her love of France is overpowering,” adds Princesse de Beauvau Craon. Yet Susan missed a few important cues. “Get me a Coke,” she once asked the tall, stunning ex-wife of a count, Birgitte de Ganay, when they were both flying back from Saint-Moritz on a private jet. “Who used to be an airline stewardess, you or me?” de Ganay says she replied. “She wanted to buy European prestige, which is very normal for an American social climber.”

“When she first arrived in Paris she was the gauchest American on high heels,” says a stylish expatriate. The social gatekeepers had a field day with her. She made her introduction to the arch-X-ray Jacqueline de Ribes, only to be rebuked for presuming to use the familiar “to” form with her. “My dear, in France you don’t tutoyer people you just met,” de Ribes reportedly said. Susan, says an onlooker, abandoned propriety and burst into childlike tears.

But Susan Gutfireund was undeterred. She felt, if not fulfilled, then at least that she had finally found her spiritual home in France. She gave her all to the effort of remaking herself, impressing even the worst snobs by learning to speak the language well, and adding three more f‘s to her repertoire—fine French furniture. To those she deemed worthy, she was attentive and kind, so much so that many of her friends in France cannot understand why people in America would want to be mean to her. “For us, she is very American in the best sense—open, free,” says art dealer and socialite Philippe Boucheny. “Perhaps in the beginning it’s difficult and you have to fight. Then when you reach a certain point, a real quality of heart appears. I am always surprised at the intensity of the competition of New York society.”

Today, back in New York, the Gutfreunds are lying low—for them. Peter, as their son is known, has been enrolled in school. John himself called European socialite Gaby van Zuylen to say he and Susan would have joined the recent weekend gathering at the van Zuylen castle in Holland except for the fact that he can’t really leave the country right now. Susan is at home on Fifth Avenue, planning backto-back dinners in October for Jayne Wrightsman and American-born baroness Didi d’Anglejan, a.k.a. Mary-Sargent Ladd, who has just written a book called The Frenchwoman’s Bedroom. She has received condolence letters as well as visits from the likes of Karl Lagerfeld and the ever loyal Givenchy. She has also been calling ladies who lunch to propose an “investment club for girls,” explaining to one woman she was seeking to enlist, “The thing of the nineties is for women to manage their own money.”

“But what is her aim in life—who is she?” The query, from a young member of European royalty, echoes the confusion that is felt among even those aristocrats who are genuinely fond of Susan Gutffeund. “I feel she wanted to create a fantasy in which she was the queen and John was the backer of the show,” this noblewoman continues. “Sometimes I thought I saw a touch of madness in her, as if she lived a fantasy life. The power of imagination is fascinating because for Susan, for a time, it really did become reality.”