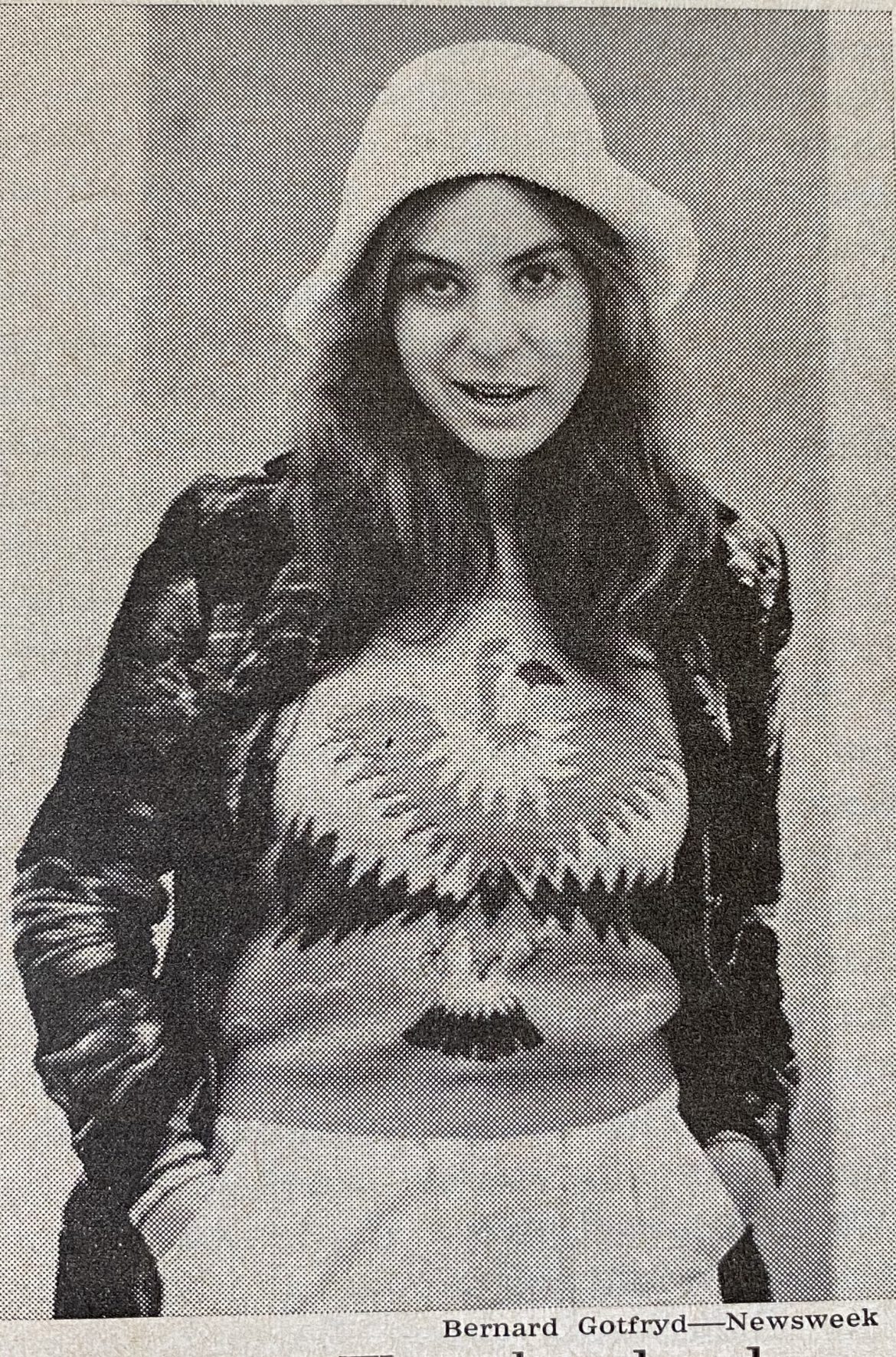

Original Publication Newsweek – January 22, 1973

Jeannie Berlin is 23, but you get the feeling you can already see her at 40 as she talks incessantly, her sharp brown eyes taking in every detail. She mugs, waves her hands, kicks her legs, even crawls on her knees for emphasis and attention. Warmth and soul bubble up from inside her, but lots of little girl is still left underneath.

As Lila in “The Heartbreak Kid,” her first major role, she plays one of life’s losers, a klutzy, trusting bride who spends her honeymoon in a Miami hotel room smearing cold cream on her sunburn while her husband falls madly in love with a blond super Wasp. Her performance, funny and excruciatingly sad, earned her the award for Best Supporting Actress from the National Society of Film Critics, plus a lot of publicity about something she had tried to play down – that she is the daughter of Elaine May, the brillian director of “Heartbreak Kid.”

Troupe: Jeannie Berlin bridles at any suggestion that she got the part because of her mother. “I had to test for the role like everyone else,” she told NEWSWEEK’s Maureen Orth. “My mother has helped me agreat deal with my acting but not at all with my career.” Jeannie Berlin comes by her histrionics naturally. Growing up in Los Angeles, she spent a lot of time with her grandmother, Ida Berlin, while her divorced mother was working. Her grandparents started a troupe that played the old Yiddish-theater circuit. It was show business on a shoestring: once they got berths on a train by telling the conductor he had a beautiful voice and hiring him for a show. Jeannie’s father, a free-lance designer, taught her acrobatics. “As a little girl I was a horror,” she says. “You know those kids who do imitations of Maurice Chevalier? I’d carry on like that.”

When she was 10, Jeannie started taking acting lessons from her mother. “She’d be so real she’d get a real reaction out of me,” Jeannie Berlin recalls. “She taught me to react to the same situation ten different ways, to pantomime it first. She taught me about substitution. In order to cry or laugh you think of a thing to make you react like that.” During high school Jeannie Berlin, who has a natural gift for teaching, began to direct school plays and work with retarded children. “The kids were a great way to learn acting, to learn behavior,” she says. “Where we have defenses they have none.”

Formal training never worked for her, and she dropped out of acting school at NYU. “The course was supposed to be special, elite,” she says, “but it was a farce. After my mother and grandmother, everything else suffered in comparison. The only thing I learned was how to juggle in the circus class.”

Clowing comes naturally to Jeannie Berlin – so naturally that she fears being typecast. She brings enormous concentration and energy to her roles, analyzing her characters endlessly on paper until she feels she knows them so well she can switch theme on and off at will.

Antics: In her professional debut she played a Beatles fan in an off-off-Broadway musical comedy. “During my audition I jumped the rock star,” recalls Jeannie. “I clawed him, I wouldn’t get off him. My mother taught me to do things for real.” Then she joined the chorus line of the same production and her antics had the audience rolling in the aisles. “I thought I was dancing just like the other girls,” she says. But there weren’t many jobs around for chorus girls with size 12 feet, so she headed out to California and got bit parts in a string of Hollywood youth films. After a small role in “Portnoy’s Complaint” she made a movie called “Bone,” which she’d prefer to forget. “Heartbreak Kid” was her first “chunky” part, as she calls it.

Today, while waiting for another chunk to come along, Jeannie Berlin has continued to instruct everybody about anything. On location for “Heartbreak” she held drama seminars for 80 students at the University of Minnesota, and she has just finished a film script (boiled down from 2,000 pages to 500) about her grandmother’s immigrant family. Her dream is to start a theater for people “who don’t have connections like agents or relatives. I’ve played with old actors and many were the same as the handicapped kids I worked with,” she says. “Both were getting older and older and they weren’t going to make it. It’s nice to help somebody else.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.