Andrew Cunanan and the killing of Gianni Versace

January 6 2018, 12:01am

The Times Magazine

On July 15, 1997, the flamboyant fashion designer was shot dead on the steps of his Miami Beach mansion. His murderer? A serial killer on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. Writer Maureen Orth’s explosive account revealed how the police failed to track him down. Now her book has been made into a TV series, with Penélope Cruz playing the woman who went on to run her brother’s empire, Donatella Versace.

In July 1997, Gianni Versace, 50, was one of the world’s most famous fashion designers. His high-octane catwalk shows were legendary. The Italian had revolutionised fashion with his blend of rock’n’roll and couture. Moves were under way to float his eponymous label on the US stock market, with the value rumoured to be as much as $1.4 billion.

At the same time, Andrew Cunanan was about to become the subject of one of the largest manhunts in FBI history. Nine days after he assassinated Versace outside the latter’s home, Cunanan’s body was found in a Miami Beach houseboat. Before the killer gained worldwide notoriety, he had already traversed a gay parallel universe – travelling from the seamy, drug-addled underbelly of the demimonde to the privileged world of the rich and the closeted.

I reported Cunanan’s story, I tried to unravel the lies and untangle the contradictions – he did not yield his secrets easily. He began life as a beautiful child with an IQ of 147. His parents had an unhappy marriage, and they counted on their youngest child to save and validate them. The gifted child was never able to form a coherent adult personality.

Cunanan could fit in anywhere. He could discourse about art and architecture, and he was a walking encyclopaedia of labels and status. No matter how much Cunanan got, he always wanted more – more drugs, kinkier sex, better wine. Somehow he came to believe that they were his due. And why not? He was always the life of the party, the smartest boy at the table. But at 27 he was also a narcissist and practised pathological liar who created alternative realities for himself and was clever enough to pull off his deceptions. In the superficial circles in which he travelled, Cunanan made himself indispensable. Beneath the charm, a sinister psychosis was brewing.

Drugs and illicit sex increasingly coarsened his instincts. He had no profession to fall back on. He had been seduced by a greedy, callous world that proffered the superficial values of youth, beauty, and money as the maximum attainments of a happy life. In the end, Andrew Cunanan, the product of a fanatically Catholic mother and a just as fanatically materialistic father, inflicted incalculable pain on others.

For years, Cunanan had been deeply jealous and resentful of the rich and famous Italian designer who “came from nothing” and who through “hard work” had become an international celebrity and gay icon. Cunanan called Gianni Versace “the worst designer ever”, and once told a friend that he was “pretentious, pompous and ostentatious”. Outwardly, Cunanan sought to keep his rage in check, but inside he seemed to be keeping a little list.

They were both southern Italians: Versace was Calabrian, Cunanan was half Sicilian. They both came from port cities and deeply Catholic environments. They both started out at roughly the same economic place, although Versace did not have the privileges of a top education. Yet here was Versace with a family he was proud of, from whom he never had to hide his gayness; a loving, long-time partner; the riches of the world at his feet. Versace’s life sounded a lot like the one Cunanan had wished for when he was a teenager.

By May 11, 1997, Cunanan had arrived undetected in Miami, having covered 1,100 miles in two days. He’d already murdered four men.

The Normandy Plaza Hotel was a few miles north of South Beach. With its pictures of Marilyn Monroe, who supposedly once stayed there, and its peeling lino floor, the Normandy Plaza was on the other side of the moon from the paradise-on-steroids that “SoBe” had become to gay travellers, but it was within walking distance of a gay nudists’ beach.

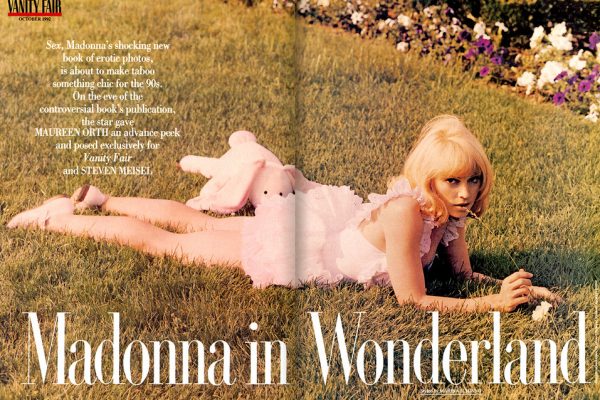

On May 12, three magazine articles of particular interest to Cunanan hit the newsstands. Both Time and Newsweek featured him as the suspect in four murders; Time called him a “gay socialite” and Newsweek an “upbeat party boy”. The third article was in Vanity Fair, which Cunanan read religiously every month. The June issue carried an article by Cathy Horyn that spotlighted Donatella Versace, the sister of Gianni, and showed off their South Beach villa, Casa Casuarina. It included a vignette of a family picnic at another gay beach across the street from the mansion, served by staff who had to wheel everything over in carts. For the Versaces, munching their sandwiches for a reporter to observe, the idea that such displays might make them a target probably didn’t occur. They were merely feeding the ever ravenous publicity beast.

South Beach was a riot of easy sleazy, where dancing the night away amid hundreds of tanned, undulating bodies was a standard prelude to anonymous sex. On a typical night at Warsaw, the first big gay nightclub in South Beach, the scene was dominated by buffed bodies that didn’t seem real; they looked pumped up, airbrushed and retouched. Woe to the also-rans in these places. “Versace used to go out to clubs all the time in the early days,” says Tom Austin, an acute chronicler of the SoBe scene.

Dana Keith, a former Versace model, explains the scene by saying, “What is the vibe of the room? What is the level of the drugs? How many cute guys are there? It’s a pretty mixed-up sense of priorities.”

Versace’s residence, the Casa Casuarina (named after the only tree on the property) at 1116 Ocean Drive, stood as a testament to another form of gay abandon. In 1992, Versace bought the old Amsterdam Palace, a run-down apartment building that had once been a grand Mediterranean villa. It had been constructed in 1930 to resemble the house in the Dominican Republic of Christopher Columbus’s son, Diego, for the grandson of the treasurer of Standard Oil, Alden Freeman. Versace paid $2.9 million for the property, which came with its own copper-domed observatory, and then scandalised the preservationists the following year by paying $3.7 million for the decrepit Revere Hotel next door and levelling it to build a patio and pool. However, the natives were impressed enough with their rich new neighbour that Versace managed to win over one of the leaders of the historic-preservation movement, who helped him run interference at city hall. After Versace spent more than $1 million on restoration and another princely sum on furnishings, the fabulous Casa Casuarina emerged – a 20,000sq ft, 10-bedroom paean to pagan excess that has been variously called “a flagrantly visible Xanadu”, “a high-camp tropical fever dream” and “a palazzo in drag” decorated in “gay baroque”.

Versace preserved the busts of Christopher Columbus, Pocahontas, Confucius and Mussolini found in the courtyard; he covered every available inch with Byzantine mosaics, Moorish tiles, Versace fabrics, Medusa heads (his logo), Picassos and Dufys; he threw in hand-painted ceilings and a few murals.

The garish blend of Versace high life and sales appeared to spew out automatically, like a personal 24-hour news service, or a never-ending video fashion reel with a familiar cast of characters: his younger sister, Donatella, 42, creative director of the company, the alter-ego muse with the platinum shank of hair out discoing night after night; her American husband, Paul Beck, in charge of Versace advertising, at home with their young children, Allegra and Daniel; their brother, Santo, the company’s CEO, a former accountant who hovered in the background and whose 1997 conviction for bribing tax officials was overturned on appeal; Versace’s long-standing companion, Antonio D’Amico; the dressmaker mother and father, who sold small kitchen appliances that gilded the designer’s humble childhood in Reggio di Calabria.

Gianni Versace paid for top photographers to shoot pictures of him, his sister and his clothes for fashion magazines. The reasoning? If he was seen on the pages of the top glossies hanging out with Elton or Sting, designing for Elizabeth Hurley the famous black dress held together with safety pins, aspiring nouveaux around the world would snatch up anything with the name Versace on it.

To someone as consumed with a similar yearning as Cunanan, such a life would be enraging. He would take umbrage at Versace’s ostentatious materialism.

Hiding in his seedy hotel room, eating takeaways and venturing forth only after dark, Cunanan would have had plenty of time to fume. From following Versace and reading about his opulent lifestyle in South Beach, Cunanan knew that given the right day, he could probably reach out and touch him. In the Vanity Fair article about life at Casa Casuarina, he read, “The Versace lifestyle is almost mind-boggling in its grasp of the consumption ethic. The message: absolute freedom.” But everywhere Cunanan turned, he was trapped.

“Cunanan was a hustler. I knew that from the moment I saw him. He was on the take. I set him up. He was very, very generous.” Ronnie is a 43-year-old gay Normandy Plaza resident. He saw Cunanan almost daily while the latter was hiding out in Miami Beach. Ronnie knows the street life around the hotel well. “I would always speak: ‘Hey, how are you?’ He finally came up and said, ‘Where can I get some rock [crack]?’ ”

Cunanan regularly bought crack from Lyle, a dealer who sold him $10, $40 or $100 rocks. “He definitely liked his dope,” Lyle says. Cunanan spent several hundred dollars a week on crack, but nobody asked any questions. For Lyle, “Cunanan just blended into the scenery. He was a loner.” Ronnie adds, “For people who are straight, the gay world is like any other. What the gay world is, is if you take care of me, I’ll take care of you. In the gay community, we don’t reveal.”

Cunanan slipped into a netherworld of prostitutes, pimps and drug dealers who frequented the neighbourhood – the underbelly of the glittery world of Versace a few miles to the south. Cunanan would contact Lyle on his beeper and often send Ronnie to pick up the drugs at the McDonald’s two blocks from the hotel. He also made a daily habit of going across the street to a liquor store and buying a pint of cheap vodka, which he sometimes downed all at once in front of the annoyed owner. When high, he’d disappear into the bathroom.

“I knew what he was doing. He was hiding. I didn’t know it was for killing people,” says Ronnie. “What happened was, I was sitting out back one day. He walks by and I’m looking at him, scoping him.

“ ‘You see something you like?’ Cunanan asked. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘You’ve got a cute ass. I could make some money off you. You hustle?’

“ ‘I’ve done that before,’ Cunanan said.

“I picked up the phone. That’s how it got started.”

He told Ronnie his name was Andy. “He never said where he was from. I set him up with a few old men, old rich guys around here. They would use my room. I got money that way.” According to Ronnie, Cunanan also made his own pickups on the gay cruising beach, which was five blocks away, or at the hotel next door catering to German tourists. “One day this guy he brought in had a Cartier bracelet,” Ronnie says. “When he left the building, he didn’t have it on.”

According to Lyle, “He was a male prostitute, but he was also doing burglaries, doing whatever he could to get money. He’d stay in the hotel all day long and he’d go out at night – sneak out the back and go in the back. Nobody knew his business.” The thefts were mostly jewellery – “Stuff,” Lyle says, “he could fit into his backpack.”

Inside his small, dingy room, which he rarely let the maids in to clean, Cunanan surrounded himself with books detailing the worlds he preferred to inhabit, and into which he could further escape. By the dim light of his shabby hideout he read mostly about the famous rich. In addition he was reading about the Arts and Crafts movement in John Updike’s essays on art, Just Looking, and Kenneth Clark’s The Romantic Rebellion, plus half a dozen other books on art and architecture and one on the artist Francis Bacon.

On July 7, it was nearly two weeks since Cunanan had last visited Lyle. Cunanan was getting desperate. He walked around the block near the hotel to the Cash on the Beach pawnshop owned by Vivian Olivia and showed her a gold coin that he had stolen from Lee Miglin, one of his previous victims. Olivia weighed the gold and told him she’d give him $190. Cunanan was upset. “Why are you paying me so little if I paid so much more for it?” he whined. “I explained to him how the pawnshop worked,” Olivia recalls. “So I asked him for his ID, and he gave me his passport, which said ‘Andrew P. Cunanan’. I asked him his address.” Cunanan answered, “6979 Collins Avenue, room 205.” Instead of his own room, 322, he had given Ronnie’s. Olivia remembers that he had a two-day growth of beard. His skin was pale and he was wearing a baseball cap and round glasses. He signed the papers, “Andrew Cunanan”.

As required by law, Olivia immediately turned over the paperwork, including a copy of Cunanan’s signed application stating he was residing at the Normandy Plaza, to the Miami Beach Police Department. There it languished.

When Cunanan’s time at the Normandy Plaza was up in the second week of July, he told Miriam Hernandez on the front desk that he would be staying only three more days.

She didn’t see Cunanan on Friday, and when she left she told her brother, Alberto, the night clerk, “322 is checking out.” Alberto was to get the last night’s rent in the morning. Friday night about 9pm, Cunanan went out for his usual fast food. Kenny Benjamin, who waited on him, thought he recognised him from America’s Most Wanted and immediately called the police. He told them there was a guy in the shop who resembled someone he’d seen on television, but he couldn’t remember which programme or what the person’s name was. He added, “Man, this is no joke.”

“OK, where is he at now?”

“He’s walking down the street, and he was just in here ordering food, but I think he just walked down the street now.”

“Is he a white male or a black male?”

“You know the guy – they profiled him on America’s Most Wanted.” Kenny had told the 911 operator, “It was the guy who killed his homosexual lover and a couple of other people, like, four people.” But there was no indication the police had any idea who he was talking about.

Unfortunately, Kenny himself was standing in front of the store’s video camera, so all it showed was him talking on the phone. Kenny made the call at a busy time. Twenty-four emergency calls were backed up. Nevertheless, the police were at Miami Subs in minutes, but by then Cunanan had disappeared.

On Friday night, Versace, Antonio and a friend had a pizza at Bang, a restaurant on Washington Avenue owned by an Italian whom Versace liked. They were relaxed and left early. Versace was still decompressing from the autumn fashion shows he had staged in Paris to rave reviews. A few blocks down the street Cunanan was sighted at Twist, a club where the FBI had previously been tipped off to look for him. Cunanan danced one dance with a hairdresser named Brad from West Palm Beach, identifying himself as Andy from California. On the dancefloor, Brad said, Cunanan had his hands all over him, grabbing and rubbing him. When Brad asked him what he did for a living, Cunanan blithely said, “I’m a serial killer.”

He laughed and said to Brad that he was really in investment banking. Then he disappeared into the crowd.

That night Cunanan was dressed rather preppily, in long trousers and a long-sleeved shirt. Twist manager Frank Scottolini, three bartenders and one of the regulars were all convinced they saw Cunanan several times over the weekend. Cunanan told one bartender, Gary Mantos, that he lived in São Paulo, Brazil, but that he was originally from San Diego, California, and that Miami reminded him of “Los Angeles in the Eighties”. He sat at the bar and talked to an older man. “He didn’t know anybody,” says Mantos. “He was trying to act fabulous.”

Jimmy Nickerson, another bartender, who also saw Cunanan on Friday from his station on the second level near the dancefloor, figured from the way Cunanan was dressed that he’d order Chivas Regal. Instead, Cunanan asked for a glass of water and bummed a cigarette from Carlos Vidal, a regular customer. To Nickerson, those were telltale signs: “He was acting like a hustler.”

Vidal is a news junkie. Not only had he followed the Cunanan case in the media, but he had also seen a poster of Cunanan in Scoop magazine. Sitting right next to him, however, he did not recognise him. He recalls only, “The guy looked slightly familiar.” They exchanged a few words. Cunanan said, “I’m down here on vacation.” Vidal also got the pickup vibes. He joked to Michael Lewis, a friend, “I’m sorry for who he picks up tonight.”

“He made me uneasy,” Vidal says, “because I had [the serial-killer idea] in the back of my mind.” Vidal got up and went downstairs to the bathroom, where notices are posted, to see if there was a poster of Cunanan. There was not. On his way downstairs, Vidal saw Cunanan go out. “I thought there should be a poster up,” he says. Frank Scottolini, the manager, had never been contacted by the authorities. “To my knowledge the FBI never contacted anyone in the bar,” Scottolini says, despite the fact that the Bureau had been told that Twist was a most likely hangout for someone like Cunanan. Back upstairs at the bar, Vidal recalls he laughed and said to Lewis, “ ‘That’s probably the serial killer.’ I’d seen him on network news. You say it, and you don’t believe it’s real.”

Nevertheless, Vidal was uncomfortable and decided to leave. On his way out around midnight, he told Scottolini, standing at the door, “I think you had a serial killer in there. That guy I saw was the serial killer.” Scottolini had also seen Cunanan, but he didn’t pay any attention. The next night Cunanan showed up again, wearing a white baseball cap, glasses, shorts and a backpack. The security camera was on at the door and, as Cunanan walked in and out quickly, Scottolini was on the street talking to his assistant manager. Scottolini recognised Cunanan and remembered what Vidal had told him. He was momentarily overwhelmed by a sickening feeling in his stomach. He turned to some friends, he remembers, and said, “ ‘There goes the gay serial killer.’ Then I dismissed it like it couldn’t be true.”

When Alberto, the night clerk, called Cunanan at 10am on Saturday morning, he said he’d be don in ten minutes to pay the rent. At 10.30, Alberto realised that Cunanan had skipped – gone out the back gate, leaving the key to 322 on the bureau. In the room, Alberto found a box for hair clippers. Cunanan had apparently shaved his head.

On Sunday night, Versace went to see the movie Contact with Antonio and a friend. He stayed in Monday night, when Cunanan was supposedly seen at Liquid, at the Fat Black Pussycat party, pretending he lived in one of the most luxurious buildings on the beach.

On Tuesday morning, Cunanan was up bright and early. So was Versace, who walked three blocks south to the News Cafe and bought five magazines. Dressed in his trademark grey and black, Gianni Versace walked back to his villa at about 8.40. Cunanan was across the street wearing shorts and a black baseball cap pulled down over his eyes. Carrying his backpack on his right shoulder, he crossed quickly and sidled past Mersiha Colakovic, who had just dropped her daughter off at school. Then, ignoring Colakovic, Cunanan walked rapidly up the first few steps in front of Versace’s mansion. Versace was bent over, fitting his key into the lock of the black wrought-iron gate. Colakovic, who had walked past the two, glanced back to take another look at Versace, whom she had recognised. Appearing completely relaxed, he had smiled at her. Now she became an eyewitness to his murder.

Versace lost consciousness instantly, his brain dead, although his heart continued to flutter and was kept beating by the paramedics who rushed him to Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. Cunanan had come up from behind, holding a .40 calibre Taurus semiautomatic belonging to his first victim, Jeff Trail. He pointed the long barrel at Versace’s neck, right behind his left ear and cheek. The first bullet cracked the base of Versace’s brain, fracturing his skull and tearing the upper part of his spinal cord and neck. Cunanan was so close to his target that the bullet produced a stippling effect – a tattoo of burned gunpowder the size of a half-dollar – on Versace’s neck. The bullet flew out of Versace’s neck and hit one of the metal railings of the gate. The bullet then broke apart, and flying metal particles hit a mourning dove in the eye. The bird died instantly and was found lying on its back in front of the mansion.

After the first shot, Versace’s head turned slightly, his eyes open. He received the second bullet through the right side of his face next to his nose. Shot from even closer range, that bullet lodged in his head and cracked the top of his skull. Versace immediately slumped to the steps in a pool of blood. Colakovic stood on the sidewalk frozen in horror – she had seen the whole thing from less than 30ft away. Cunanan, displaying utter sangfroid, walked calmly away down Ocean Drive. Colakovic remembered that he walked oddly, like Donald Duck, with his feet turned out.

Almost instantly, the front door of Casa Casuarina flew open. Antonio was the first to reach Versace. “No! No!” he cried. Lazaro Quintana, who lived nearby and had come over to play tennis with Antonio, saw Colakovic in front of the house. “What happened?” he demanded. She simply pointed to Cunanan, now halfway down the block, going towards Twelfth Street. Quintana gave pursuit.

Across the street and down from the Casa Casuarina, Victor Montenegro, a city employee who was fixing a parking meter between Tenth and Eleventh, heard the first gunshot. He looked up in time to see Cunanan fire the second shot into Versace’s face and then coolly walk away on Ocean Drive. Montenegro radioed police and ran towards Versace. Meanwhile, inside the mansion, Charles Podesta, Versace’s cook, called 911 at 8.44am. “A man’s been shot. Please, immediately, please!” Cops on bikes showed up in two minutes to find Versace sprawled on the steps. Hotel Astor employee David Rodriguez was on his way to work when he heard a shot and then, a few minutes later, saw Versace’s body on the steps, with people slowly gathering round. Versace’s sandals were left behind, and his sunglasses had tumbled down the steps. Rodriguez says, “I looked all around for a camera; it seemed so set up.” When he arrived at the Astor, he told Laura Sheridan, the manager, “They’re shooting a movie at Versace’s house.” If the scene itself seemed unreal, the aftermath was even more so.

Extracted from Vulgar Favours: the Assassination of Gianni Versace by Maureen Orth (BBC Books, £8.99). American Crime Story: the Assassination of Gianni Versace is on BBC TV in the spring

photo: Evelyn Hofer/Getty Images

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/andrew-cunanan-and-the-killing-of-gianni-versace-jn2r6b2g6

No Comments