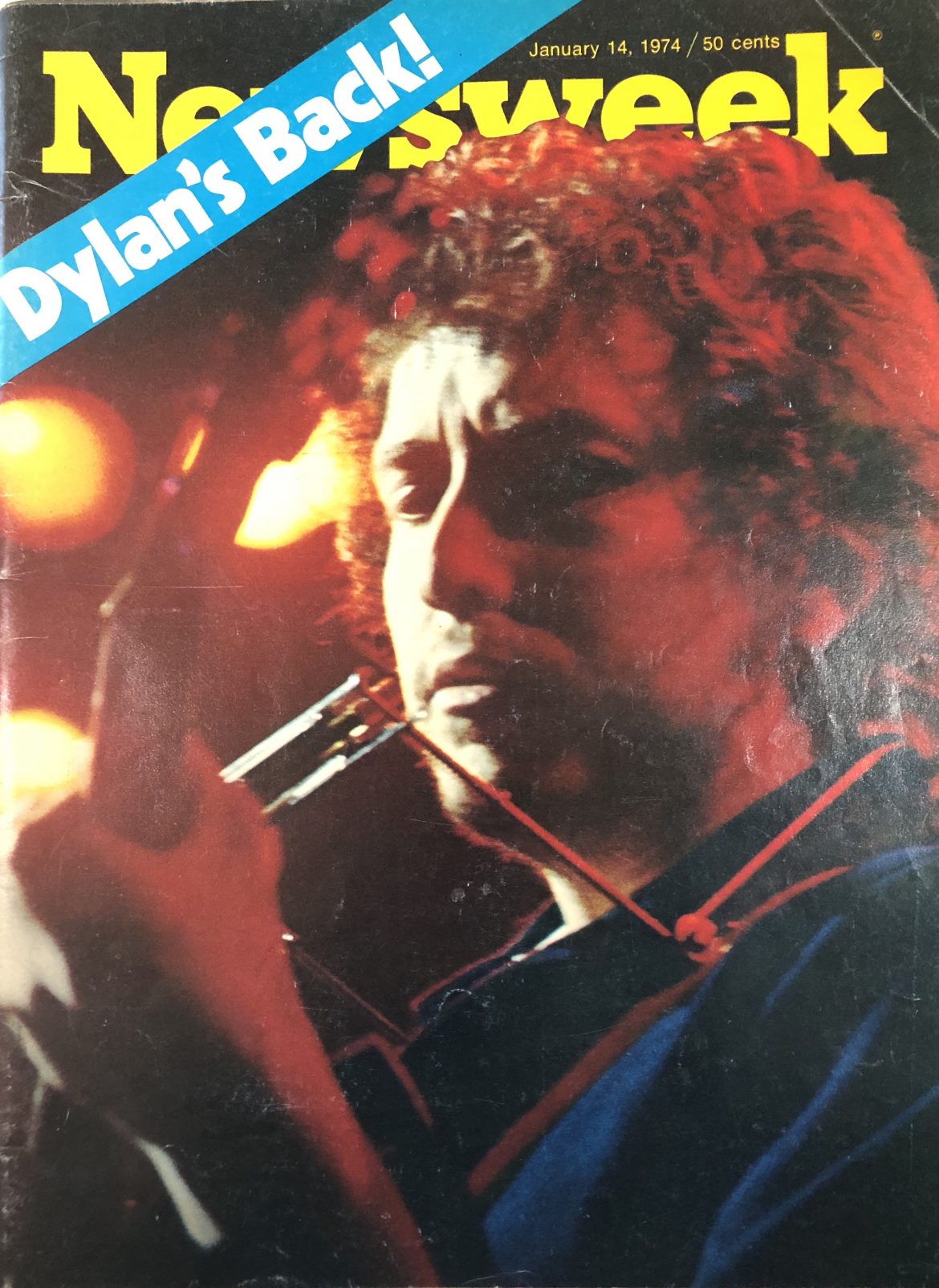

Original Publication: Newsweek, January 14, 1974

Moments before Bob Dylan began his first concert appearance in eight years, the backstage area at Chicago Stadium last week was eerily quiet. Reporters, who had swarmed in from every continent were barred – except a Newsweek reporter. There were no wives, no groupies, no hangers-on. In one small room Dylan and members of his accompanying group, The Band, twanged a few chords. In another room someone had left Dylan a surreal set of props: grotesque rubber masks, a stovepipe hat, a Keystone Cop helmet – even a crown. But for this first concert of his heralded return, Dylan disdained the disguises.

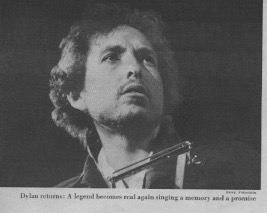

When he stepped out onstage, the 32-year-old Dylan, the elusive, reclusive poet-songwriter whose songs of protest and love sparked, sensitized and inspired an entire generation, was the Dylan everyone remembered: skinny, hunched over, dressed simply in blue jeans and black wool shirt, an old muffler thrown round his neck. Time had filled out his face slightly and given his voice a strengthened authority.

This was not the teen-age Bob Dylan who in 1960 arrived in Greenwich Village from Hibbing, Minn., looking, as one critic wrote, like “a cross between a choirboy and a beatnik,” and, given a push by Joan Baez, started a new era in America’s pop music. For years, city kids had been sitting on the floors at parties picking guitars and singing folk songs. Dylan took this urban-folk semitradition, married it to the emerging rock beat and turned out a stream of songs that told an uneasy young generation why the American dream had turned into “Desolation Row.”

Like a poet laureate, in the early ‘60s Dylan found the words that expressed a prophecy and a state of mind: “A hard rain’s gonna fall . . .” “Something’s happening here. You don’t know what it is do you, Mr. Jones?” “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows” (which gave the violent Weatherman group its name). Ironically, as if to mark the end of an era, on the day Dylan opened last week Federal Judge Julius Hoffman dismissed indictments against twelve Weathermen for their “days of rage” rampage in Chicago five years ago.

The question was: what was Dylan’s new message for the 70s? To get the answer, 19,000 fans, many busing, hitchhiking or driving hundreds of miles, braved a freezing Chicago evening to see and hear the minstrel who withdrew in 1966 at the height of his fame, told the world to get lost and like Garbo, raised the status of celebrity to myth. These people in the Chicago audience were not the screaming teeny-boppers who come to the saturnalias of the new pop stars like Alice Cooper. These were eager, expectant people, mostly in their 20s, who sat patiently as the house lights went down and only an occasional whiff of marijuana arose.

When Dylan finally walked calmly out, turned his back to the audience and began tuning up with Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson – the gifted members of his original backup group, The Band – the audience cheered him not with the demoniac sounds of Mick Jagger’s vicarious street-fighting men, but with the healthy gladness of friends greeting a long-absent friend.

Dylan came on without gimmicks. His songs, at their best, were dynamite, cutting through the crowd like a laser beam, the substance and mastery of the lyrics standing out in stark contrast to so much of the theatricality that has taken the place of music in today’s rock world. Dylan and The Band did 28 songs – all vintage Dylan except for three new ones from his forthcoming album, “Planet Waves.” Like pro athletes coming off a long layoff, their playing was ragged, almost deliberately unassuming.

But the mood changed in the second half of the show when Dylan – who never spoke during the concert except to announce the intermission – walked out alone, his black shirt replaced by a snow-white tunic. When he picked up his acoustic guitar and began blowing his harmonica, Dylan started blowing a few minds as well; when he wailed “The times they are a changin’ ” the audience roared. It was both a memory and a promise. When he sang “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” the song about the death of a black woman killed by a cane carelessly thrown by a Maryland society snob who beat the rap “through high office relations in the state of Maryland,” the reference to Spiro Agnew was perfectly clear.

He closed with “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” At the line “Even the President of the U.S. must have to stand naked,” the crowd went wild. The lyrics even inspired one man to rip off his clothes and declare his Presidential candidacy on the spot. He was immediately tackled by rock impresario Bill Graham, producer of the tour, who had earlier worried that things were “going too smoothly.” When Dylan finished, thousands in the crowd lit matches and, holding them up like tiny torches, begged him to come back. He reappeared for a finale with The Band, and the last song seemed to carry a certain message:

Time will tell who was fell

And who was left behind,

When you go your way

And I go mine.

Dylan spat out the final words like a challenge. After eight long years the most important single personality in the American popular culture of his generation was back.

“This event is the biggest thing of its kind in the history of show business,” modestly declared David Geffen, the 30-year-old human dynamo, “Record Executive of the Year,” chairman of the board of Elektra/Asylum Records, who just pulled off one of the great coups in the music business – signing Dylan away from Columbia Records. When newspapers carried an ad last Dec. 2 saying Dylan and The Band would be touring 21 cities for six weeks in January and February, the post office was flooded with millions of envelopes.

Only mail orders were accepted because Dylan wanted all age groups to have an equal chance to hear him, not just the kids who would stand in line at the box office for days before. Even so, the scramble for tickets has become frantic, including magazine ads offering bodies in exchange for tickets and scattered instances of counterfeiting. The total concert capacity was 658,000, and Geffen estimated 2 million to 3 million envelopes were sent back. With prices as high as $9.50 and $10.50, the concerts will gross a cool $5 million.

Since Dylan long ago became a millionaire, it would be downright vulgar to consider money as a motive for his return. He says he just wanted to hear good music. But whose? “If there was something else out there to really give you a kick,” declares Dylan, “I would have thought differently about doing this. What I want to hear I can’t hear so I have to make it myself.” “Bob’s a street cat.” says his friend Barry Feinstein. “It’s not good for him to be off the street.” Dylan has astrological reasons as well. “Saturn has been an obstacle in my planetary system,” he explains. “It’s been there for the last few ages and just removed itself from my system. I feel free and unburdened.”

There are other hypotheses about his return. Super-Dylanologist A.J. Weberman, who became famous by going through Dylan’s garbage cans for relics of Saint Bob, now thinks the tour smells suspiciously like a Zionist plot. “He’s doing it now because of the war in the Middle East,” Weberman insists. “He is an ultra Zionist. He is doing the tour to raise money for Israel. He has given large sums of money to Israel in the name of Abraham Zimmerman [Dylan’s father’s name]. He’s very ethno-oriented.” “I got blue eyes,” says Dylan. “I don’t know how Jewish that is.”

Dylan’s motives for doing anything have always been questioned by his idolatrous masses, and after a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 1966 he withdrew into seclusion in Woodstock, N.Y., with his wife, Sarah, emerging just four times to perform, most notably at the concert for Bangladesh. Since then he has shunned interviews, occasionally released albums, popped up in Sam Peckinpah’s film “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” and moved with his family from Woodstock to the beach at Malibu.

More important than Dylan’s own motives for coming back, which are obviously as mixed as anybody’s from Frank Sinatra to Muhammad Ali, are the expectations of his fans. Typical of these is Jim Krizmanich, a 28-year-old part-time builder of geodesic domes who came all the way from Indianapolis to Chicago to see the Dylan concert. His face stubbled, his hair uncombed, Krizmanich explains that he intends to see at least thirteen of the concerts around the country. “I just really like the man,” he told Newsweek’s Martin Weston, “but he’s not a god; more like a genius.”

Like Krizmanich, 17-year-old Andrea Deedrick has about a hundred Dylan records and tapes, including many of the pirated recordings that have become collectors’ items. Andrea came from Milwaukee with a girlfriend – and her mother and father, a 47-year-old, dark suited advertising executive. “You couldn’t classify my wife and myself as rock freaks,” says Don Deedrick, “but Dylan isn’t Tin Pan Alley stuff. The difference is his message.” “Our generation didn’t accept the protest of the ‘60s at the time,” says Andrea’s mother, Mrs. Valerie Deedrick. “Dylan was disgusted with parts of society as we all were, but he put it into music. He helped to bring a lot of my generation around to realizing some of the falseness in our society.”

But for Andrea, Dylan’s message isn’t in the lyrics. “He’s been important to me for so long,” she says. “I don’t get deep messages I just get a mood.” A budding painter, she has portrayed Dylan several times. “I just know him by heart, like most of his songs. I think he’s the most important musician who ever lived – more important than Ludwig van Beethoven.”

But there was no doubt that the older people at the concert, like Andrea’s parents, were hoping for something new to chew on from Dylan. “I’m looking for a sign or a message in his coming back,” says musician Mark Fishman of Milwaukee. “I think this is the start of a new era. In the fourth year of each decade since ’54 a new era of music has started in America. In ’54 it was Elvis, in ’64 the Beatles, and we’re all waiting to see if it happens again.” Painter Ronald Oeller of Phoenix, Ariz., has similar expectations. “I’ve seen Dylan influence music, clothing, hair, and everything else,” says Oeller. “I’m looking for something new again. He’s a leader, a pacesetter.”

Back in his hotel suite after his performance, in the company of a longtime high-school friend, Louie Hern, who knows him from Hibbing days when he was Bobby Zimmerman, Dylan is quietly watching an old Western on TV. The wool muffler is still wound around his neck. In person he’s not nearly so hard-looking as his photographs – he seems almost fragile. A little later when everyone has gone, Dylan is remote but not unfriendly.

He feels good about his performance. “It’s as natural for me to do it as for a fish to swim,” declares Dylan. “It felt just like yesterday pounding the streets.” Musically, he says, he doesn’t consider his taste a part of the nostalgia so fashionable today in pop. “I just carry that other time around with me,” he says. “The music of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s when music was at that root level – that for me is meaningful music. The singers and musicians I grew up with transcend nostalgia – Buddy Holly and Johnny Ace are just as valid to me today as then.”

Any thoughts of taking up the mantle again for a new generation are also quickly dispelled. “I am not looking to be that new messiah. That’s not in the cards for me. I like the way Van Morrison sings it: ‘You know I just can’t help you now. It’s not my job at all.’ I go deep and far out to get my songs – that’s what it is, there’s no more than that.”

Dylan made his original impact on a generation in which “nobody was thinking about anything. Now there’s so much going on everybody’s thinking the same thing. There’s a new generation of people now, a new time,” he says. “My father had to sweat. My father lived in a lot of pain. In this earthly body he didn’t transcend the pain. I’ve transcended that pain, the pain of material things.” It helps to be a millionaire, doesn’t it? “I’d be doing what I’m doing if I was a millionaire or not, whether I was getting paid for it or not. In the ‘60s there was a certain bunch of us who came through the wars. There was a lot of death during that time. The ‘60s were filled with it. It has helped me to grow up. The ‘70s are more realistic, but the ‘60s exposed the roots of that realism.”

The thought that he is an “idol” makes him uncomfortable. “Idols are old hat. They aren’t people, they’re objects. But I’m no object,” insists Dylan. “When we think of idols we think of those carved pieces of wood and stone people can relate to – that’s what an idol is. They do the same thing to someone like Marlon Brando – they attach themselves to certain people because of a need. But I’m just doing exactly what a lot of other people would be doing if they could. I’m not standing at an altar, I’m working in the marketplace.”

When Dylan mentions the marketplace he knows what he is talking about. He is one of the two or three most valuable properties in the multimillion-dollar-a-year pop-music business. Columbia Records, his previous label, was not unaware of this situation. When Dylan’s contract with Columbia Records ran out last year he did not renew it, switching to Asylum instead. Columbia immediately got up an album filled with Dylan “outtakes” he had discarded in the studio long ago. Columbia promised Dylan that if he re-signed with them the album would not be released. He didn’t and it was.

When Dylan and The Band decided to go on tour, they worried at first that their brand of music wasn’t enough to impress a new audience of people used to seeing the theatrics of “decadent” rock stars like Alice Cooper or David Bowie. And they hadn’t forgotten Dylan’s hectic, less than triumphant tour in 1965, when, said lead guitarist Robbie Robertson last week, “we were booed off of every stage in Europe. What happened tonight in Chicago is so reassuring for us. We don’t have any fancy outfits or sparklers on our eyes, and we don’t cut off any heads. I mean how many times can you set yourself on fire or rip off your shirt?”

Dylan’s direct, straightforward appeal to an audience is related to his celebrated reluctances to allow the media to interpret him to the public. “I’ve never bargained to be accessible to the press or the media,” Dylan declares. “They’ve yet to find anything that they’re gonna get from me. What I do is direct contact between me and the people who hear the songs and that goes right to the heart of the matter. It doesn’t need a translator.”

But Dylan has his own kind of charm, which he can turn on even in the presence of the media. He walks around his hotel room balancing a straw boater on his head, reacting enthusiastically to stories about country singers, such as Dolly Parton’s armory of wigs. He talks about books – especially books that have the word solitude in their titles – “A Hundred Years of Solitude,” “A Woman Called Solitude”.

When the reviews of his concert came in, he read them eagerly. “Wow,” he exclaimed as he looked over the Chicago papers (which were generally raves), “this guy thinks ‘Forever Young’ [a song from Dylan’s forthcoming album that’s a kind of prayer to his children] will be big on high-school and college campuses.” Dylan shook his head in genuine disbelief. “Now how could he say a thing like that?” Another column suggests that Dylan, just by dropping in, tore a local club apart. “Hey, let’s call all the newspapers and say Bob Dylan is coming! We’ll meet ‘em on a street corner! Call the TV cameras!”

Dylan, shy, evasive, wary of “profundity” and of claims on his privacy, nevertheless is an artist in close contact with his audience. He sang “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” opening night because a man from his hometown had written him a letter reminding him how relevant that song was to today’s politics. But feeling a responsibility toward his fans is another matter. “There’s the hard core and the curious,” he says. “I’m not surprised by the response we’ve had for tickets to the tour, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they only sold 1,000 tickets. I give out a hard dose – like penicillin. People don’t have to worry if Dylan’s conning them. If it works, it works. If they don’t like it, they don’t have to try the dose again.”

As an artist Dylan seems to have found confidence. As a performer he’s more relaxed. “A lot of the nervousness has gone. I used to feel nervous all the time before I went onstage.” As a husband and father (five children) he has found profound love.

Dylan has come back at a time when our society is starved for heroes. His problem is he doesn’t want to be a hero any more. He’s singing his songs in his old way, and to many in 1974 they sound fresh and welcome – daring people to think about things few of the leaders of the ‘70s are talking about. But this doesn’t seem like the moment when a singer, no matter how charismatic, is going to change people’s consciousness. A minstrel cannot compete with the whipsaw of reality in the ‘70s. Maybe Bob Dylan should be treated as he wants to be – as a musician pure and simple. It may be that he himself is still “a rolling stone,” looking for something. As he sings in a new song:

There are those who worship loneliness –

I’m not one of them.

In this age of fiber glass

I’m searching for a gem.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.