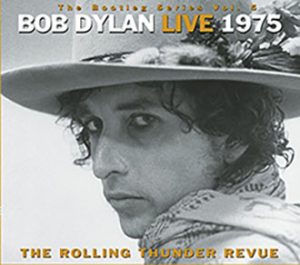

Original Publication: Newsweek — 11/17/1975

One dawn last week, Bob Dylan slid behind the wheel of his new mobile home and drove to a rocky point behind a Gatsby-like mansion in Newport, R.I. Soon he was joined by folksinger Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, poet Allen Ginsberg, Ronee Blakley (country-singing star of “Nashville”), Roger McGuinn (leader of the now-defunct Byrds), an assortment of lesser-knowns and hangers-on, and Rolling Thunder, a celebrated Cherokee medicine man. The group formed a circle around a small fire, and Rolling Thunder, who had earlier phoned the Coast Guard for the exact time of sunrise, raised an eagle feather, pointed it heavenward, then waved it at the gathering.

“Music comes from the earth to fill our souls,” Rolling Thunder intoned. One by one, each of the celebrants sprinkled some tobacco into the smoldering fire, and when it was Dylan’s turn, he stepped forward and whispered: “We are of one soul.” At the ceremony’s end, he had a tear in his eye.

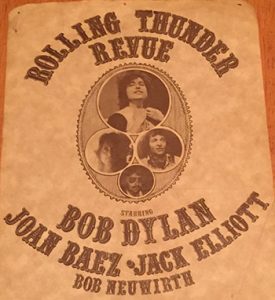

Caravan: No rock star has been more conscious of his mystique – and the media’s consciousness of it – than Dylan. He has shed images as fast as Nixon and is beginning to come back as often as Sinatra. But at a time when rock is bloated with media hype and scattered in dozens of directions, he has come back once more with the larger purpose of bringing it all back home. With rock now oriented toward superstars in superdomes, Dylan has decided to share small stages with old friends and provide a platform for complete unknowns. His new tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue, is not playing Madison Square Garden as Dylan did when he came back in January 1974. Instead, he and his circuslike caravan of 70 musicians, filmmakers, oldline Village beats and mainline crazies are traveling by bus throughout New England for gigs in places like Durham, N.H., and Lowell, Mass.

Besides making music, the troupe is also making a movie of itself, but Dylan only hopes to break even on the tour. Like his excellent new music, he seems less metaphorical and more accessible. “This is the great moment of Dylan taking off his mask,” says Ginsberg, who is on hand as fellow traveler and to play the finger cymbals in the show’s finale. “He’s accepted the myth created around him and is transferring it into artistic energy. He’s alchemizing it into gold.”

Jamming: The idea for the tour began last summer when Dylan, 34, left his wife, Sarah, and five children home in Malibu, and started hanging out at the folk clubs in Greenwich Village where he got his start. One night, he and Ramblin’ Jack and old buddy Bobby Neuwirth were jamming afterhours. “We’re singin’ and pickin’,” recalls Jack, “and suddenly Dylan says, ‘We ought to do a tour!'”

Dylan, meanwhile, had been introduced by Roger McGuinn to the off-off-Broadway director Jacques Levy (“Oh! Calcutta!”). Soon Dylan and Levy were collaborating on the lyrics for a new record album, which Columbia plans to release in January. Dylan also read Rubin (Hurricane) Carter’s book – the story of the former middleweight contender’s alleged frame-up on a murder rap – and began to visit Carter in prison. Dylan and Levy set Carter’s story to music, and “Hurricane,” Dylan’s recently released single, is his most powerful protest song in years.

In September, Dylan invited Joan Baez, his former love and co-star in the 1967 documentary “Don’t Look Back,” to join his tour. He also asked Ginsberg – on his way to a Buddhist retreat – and the avant-garde playwright Sam Shepard to help write the movie, which is expected to feature everything from Ginsberg and Dylan mourning over the grave of Jack Kerouac to Ronee Blakley playing a witch. “Dylan has a peculiar magnetic power,” says Shepard. “When he’s in a room he pulls people to him and when he’s in front of the camera he does the same thing.”

Despite Dylan’s new accessibility, he still maintains his old antipathy toward the press. At his opening concert, in Plymouth, Mass., photographers’s cameras were confiscated and a nosy Village Voice reporter was held in his motel room by two Dylan security guards. But onstage at the Civic Center in Providence last week, Dylan, who walked on in whiteface wearing an Indian sombrero with red carnation on it, was so loose he actually began to boogie.

Fun for All: The three-hour show – with a top ticket price of $7.50 – featured performers who ranged from British rockers to old folkies. “The emphasis is on fun,” said Baez afterward. “The egos are out the window on this tour.” Dylan himself mixed old favorites like “It Ain’t Me, Babe” with new material – “Durango,” the El Dylano version of Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” and “Isis,” a striking new love song. His voice was stronger than ever, vibrant and in full control.

Fun for All: The three-hour show – with a top ticket price of $7.50 – featured performers who ranged from British rockers to old folkies. “The emphasis is on fun,” said Baez afterward. “The egos are out the window on this tour.” Dylan himself mixed old favorites like “It Ain’t Me, Babe” with new material – “Durango,” the El Dylano version of Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” and “Isis,” a striking new love song. His voice was stronger than ever, vibrant and in full control.

The second half of the revue opened with Baez and Dylan doing a duet of “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” They looked like a couple of teen-agers, and suddenly everything was so open and folksy it felt like a hip version of the Grand Ole Opry. Dylan sang the two best songs of the night, “Hurricane” and “Sarah,” a moving love song to his wife – “my sweet virgin angel, love of my life” – and the evening ended with a rousing sing-along of “This Land Is Your Land.”

Clearly, Dylan has opened up creatively and is letting his feelings pour out. “Bob, Joan, myself, we’ve all transcended our hangups,” declared Ginsberg after the show. Whatever hangups he may have transcended Dylan declined to reveal. What, then, had prompted his new burst of creative energy? “The answer,” he replied with a straight face, “is blowin’ in the wind.”