On the Richter scale of high divadom, this is a major quake. Melina Mercouri’s whole body is racked with sobs. “My life is sheeet!” she shrieks in Hellenic English. “I don’t want to fight anymore. I just want to be alone!” For a nanosecond she seems to forget that her devoted husband, film director Jules Dassin, is sitting next to her. “I just want to be alone with my husband!” she wails without missing a beat.

“Oh sure,” laughs Dassin. “Wouldn’t that be something?”

It is the morning after. Late the night before, Melina Mercouri, the most powerful woman in Greece, formerly both a major motion-picture star and the country’s flamboyant minister of culture, lost her bid to become mayor of Athens. Her defeat is humiliating. Her fellow Athenians have rejected her, rejected her attempt to follow in the footsteps of her famous grandfather, who had been mayor for thirty years. Not only the Athenians, the very gods of politics have betrayed her.

Mercuori looks haggard but mildly glamorous in her long turquoise silk dressing gown embroidered with pink beads and her gold lamé slippers that match her honey-colored hair. She also looks fierce, and reinforces this effect by crushing a pack of unfiltered Greek cigarettes in her palm while glaring at her companions: her husband, her brother, Spiro, who functioned as her campaign manager, and her close friend actress Despo Diamantidou. This American reporter is especially unwelcome.

La Mercurial throws her glasses across a table and buries her face in her arms. “Today I think my life has been mostly nightmares.” Her smoky voice is hoarse and cracked. “I am so ashamed.”

Mercouri, now seventy-one (more or less), is used to getting her way. No one close to her, including her husband, thought it was a remotely good idea to run for mayor, but since she was practically the only remaining scandal-free figure of note in the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) – the party she helped found in the mid-seventies, when the dictatorial Colonels were overthrown – she accepted the baton, assuming there was no way she could possibly drop it. Now the anterooms of Mercouri’s four-story house in Athens’s Kolonaki section, the same posh neighborhood where she grew up, are filled with morosely quite PASOK officials, their faces buried in newspapers. In early September the polls said Mercouri was the most popular politician in Greece – six weeks later she has managed only 46 percent of the local vote. Worse, all of Athens is whispering that she conducted a frivolous campaign, full of platitudes instead of programs. A few days before the election, her colorful opponent, Antonis Tritsis, a former socialist Cabinet minister who broke with the left, had complained that all Melina Mercouri would take a stand on was her love for the city. “She talks about these . . . these feelings. About love . . . It’s like running against a U.F.O.”

According to Spiro, however, this was deliberate. “Her campaign is based on emotion because Athens has so many problems that you can’t do anything unless you make people feel a part of the solution. It’s not a matter of doing this or that, but saying, Come on, let’s do it together.” And, more practically, since the conservative central government controls the municipal budget, promises might be heard to keep for a vociferous member of the party out of power. Plus, as Mercouri’s French political consultant pointed out on election night, “she’s an actress, not a political girl.” Outside her campaign headquarters in Athens, a huge grid of sixteen TV screen mounted above the sidewalk had featured scenes from her signature film, Never on Sunday, as well as clips of Mercouri’s meetings with world leaders and excerpts from a 60 Minutes interview. The message was that Melina Mercouri is a great star and patriot, able to attract international attention for Greece – which needs all the help it can get these days because of its high inflation rate and huge foreign debt. The images were a reminder that the mayor can ask the European Community for funding for specific projects and can also go abroad for loans. Mercouri’s ability on the foreign front has always been one of her most potent political assets.

“I want to make Athens again a city that has glamour, pride, and a conscience, to do whatever I can for this city that I loved as a child,” she said. But it probably didn’t occur to Mercouri as she repeatedly thrust her arms in the air and gave the V sign with both hands or stared transfixed at her image up on the grid of TV screens that glamour, bravado, and bravery might not be enough anymore in a city fraught with more than its share of end-of-the-millennium problems.

A prominent architect has described modern-day Athens as “a visual wound.” Although the boundaries of the old city, and the parameters of the mayor’s power, are still drawn as they were in her grandfather’s day, much of the far more charming city Mercouri grew up in is gone – sacrificed to greed and the need for space. Worse, pollution is eating away at the city’s largest dollar, yen, and mark draw: its incomparable repository of classical architecture, which has withered away more in the last twenty-five years than in all the time since its creation in 500 B.C. Until recently so little has been done to control pollution that for many days of the year Athenians are virtually held hostage to the dread nephos – the Athenians’ word for their black cloud – air so unhealthy it is hard to breath without choking.

In the last fifty years, Athens has survived a World War, undeclared civil war, wave upon wave of villagers who want to be urbanites, and the return of thousands of expatriate Greeks who came rushing home when politics allowed it – swelling the population of the city and its environs to three million, or one-third of the entire country. The result is that some Athens neighborhoods are more densely populated than Singapore. There are virtually no sidewalks in many places, let alone shrubbery, and traffic is in a permanent snarl, particularly in the center of the city, where the government bureaus are concentrated.

Yet for all the horrors that plague Athens, it is still one of the more humane cities in the Western world. There are no homeless wandering the streets. Buildings are rarely higher than several stories. Neighborhoods are vibrant and alive – the Greek family is still largely intact, and the police walk around with unloaded guns. The city is so safe that a woman can wander alone at night and never have to be afraid. Compared with, say, the citizens of New York, Los Angeles, or even Milan, Athenians don’t have that much to complain about – but they do anyway, constantly, among themselves and in the city’s seventeen contentious daily newspapers. “We like complaining,” says Fotini Papathanou, a political scientist. “People have very strong negative feelings about Athens, but everybody keeps on coming here – it’s a love-hate relationship.” When I asked the outgoing mayor, Nikolas Yatrakos, how many murders had been committed in Athens in the last year, he said, “You mean apart from traffic fatalities? I guess about three or four.” Yatrakos, a member of the ruling conservative party, New Democracy, had not been permitted to run against Mercouri. “I’m not a movie star,” the rather lackluster economist explained.

Last April the New Democracy party had gained control of the national government from PASOK and the left, but not by much of a margin (a single seat), considering that PASOK’s leader, former prime minister Andreas Papandreou, along with many of his colleagues, had been involved in a bribery scandal. Papandreou had also divorced his longtime American wife to marry his mistress (a flight attendant nearly half his age), had suffered a heart attack, allegedly consulted an astrologer daily, and left the country in economic chaos. However, since the new government’s harsh austerity measures shocked a populace used to being under socialist protection, most of Athens went on strike only a few weeks before the mayoral election. Many viewed the mayor’s race as a referendum on the national government. “We are really running two elections here,” noted Tritsis, who was campaigning against Mercouri on the New Democracy ticket. “One is national, the other is local.”

It was a bold stroke for PASOK – if not a desperate one – to offer the popular Melina for mayor. In response, and to distance themselves from defeat if she was elected, the conservative New Democracy party had backed Tritsis, a mustachioed former minister of education and the environment in the leftist government who had fallen out with the socialists two years ago and lost his Cabinet seat. To many conservatives, he is still suspiciously liberal, however, and not a team player. In some circles, Tritsis, fifty-three, a former decathlon champion and city planner with an American Ph.D., is considered a gadfly and an eccentric. But he proved to be an energetic campaigner who thrilled audiences with rhetorical flourishes and myriad schemes to fix Athens.

“I will break the asphalt,” he promised, explaining that he would create a new archeological park around the Acropolis by eliminated the roadway which currently carries tourists up to the decaying wonder of the world. So then how would the tourists get to the Acropolis? “On their knees!”

Melina wanted to break the asphalt too – somewhere in her campaign literature she said so. But the idea of her vigorously attacking the city’s problems and protecting its precious heritage didn’t come across on TV, where much of the election was decided. She looked frail and off her game. Privately, she was like a raging faucet. “You never know which one you’re going to get when you go over there,” said Despo Diamantidou, “hot or cold.” Her friends, already concerned about her health, despaired. She was simply not the old Melina. But, looking wild-eyed and fearful at times, she stubbornly plowed on. “She feels disarmed of her charm – the main weapon she’s had in life is gone,” said a woman who has known her for years. “The glorious Melina is like a frigate in full sail. With this campaign she is demystifying herself.”

But, ah, what a myth.

“Either you eat men or be eaten by them – make your choice,” Melina Mercouri’s beautiful mother taught her, and indeed it has been she who has seduced and devoured for the better part of her life, most visibly at first as the happy hooker in Never on Sunday (1960), and then as the passionate soul of the opposition starting in the late sixties, when the repressive Colonels ruled Greece, and finally as the charismatic minister of culture in the government of Andreas Papandreou, the socialist prime minister who replaced the fascistic Colonels. Mercouri became the symbol of Greek national identity. “I know just enough English to wince along with you when I mispronounce,” she said during a lecture in London. “Permit me then to launch our theme with a few Greek words: Music, Drama, Tragedy, Comedy, Theater, Choreography, Philosophy, History, Democracy. All Greek words . . .” “Melina is an exhibitionist of the mind,” says her brother.

Her magic on the screen, however, was anything but cerebral. “She has a very aggressive sexuality, which is rare in a female film star,” says Peter Aspden, a British journalist who has written about Mercouri in a forthcoming book on what makes certain actors explode into mega-stardom. “It’s almost masculine. She’s always been rather emancipated – she knows what she wants and she knows how to get it. The irony is that all this emerged on the screen in the fifties and in Greece.”

Stella, her first movie, directed by Michael Cacoyannis on a budget of about $30,000, burst into view at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival and astounded its audiences. Mercouri was in turn alluring, selfish, warm, self-centered, and charming, and when she sang she smoldered. Filmed in gritty black-and-white, it is the story (written especially for her) of a singer in a bouzouki café who refuses to marry, for fear she will lose her freedom. In the end she must die for having loved too many men (even though one at a time) and for leaving an archetypal Greek male, a soccer star, at the altar. “To see this macho Greek man led by this woman – it had an incredibly powerful effect,” says Aspden. Especially in Greece. Yet Stella is Melina Mercouri’s only film in Greek, and she had to wait until she was an established stage actress and in her thirties to make it. “She had been ignored by filmmakers until then,” says Cacoyannis, “because they thought her mouth was too big.”

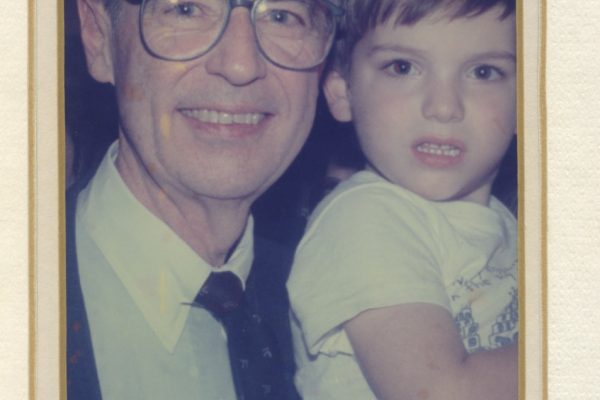

Jules Dassin, a blacklisted American director from the Bronx who had begun working successfully in France, saw Melina for the first time at Cannes in Stella. He was looking for a Greek actress to play a secondary role in a film he was adapting from a story by Nikos Kazantzakis – and Mercouri knocked him dead. Dassin remembers that when he met Melina she was “more or less the same wild creature I saw up on the screen.” At the time, he was married with three children and not planning a divorce.

Dassin’s wife decided to stay at home while he shot the Kazantzakis film in Greece – a big break for Melina, who was not shy about her feelings for him. “A man could not escape when she wanted him,” says Deni Vachliotou, an old friend who did the costumes for Never on Sunday. “She had such success with men. She provoked them to the point they went after her.” And from that moment on, Melina Mercouri and Jules Dassin – whom many characterize as “a saint” – have had an extremely close personal and professional collaboration. “Thirty-two years I am with Julie, and he has never lied to me or told me anything that is second-rate,” Mercouri says. And, of course, it was Dassin who made her a star.

Never on Sunday, written and directed by Dassin, began life as The Happy Whore and has probably done more for tourism in Greece than anything since the building of the Parthenon. It had sun, it had the sea, it had Melina. In 1960, at a moment when U.S. audiences could choose between Sandra Dee, Elizabeth Taylor, Annette Funicello, and Marilyn Monroe, Melina Mercouri hit the screen as incredibly sexy, forthright, unneurotic, and uncontrived – “able to devour ouzo, men, city corruption, and American imperialism in equal measure,” Peter Aspden notes. Dassin created a character of sunny, unbridled optimism who even makes up happy endings to the Greek tragedies – a trait inspired by Melina’s mother. “It came from our differing interpretations of the Bible,” says Dassin, who is Jewish. “Melina’s mother did not believe Christ was crucified, he didn’t die on the cross, and he wasn’t a Jew.”

Mercouri’s captivating performance was enhanced considerably by a bouzouki-music score and an Oscar-winning title song. Inside the industry, it didn’t hurt either that the film was launched with an unforgettable party on the French Riviera complete with imported bouzouki players, hundreds of European jet-setters linking arms and dancing Greek folk dances, and the traditional breaking of several hundred pounds of crockery. “I knew we had a hit,” says Alain Bernheim, Dassin’s agent at the time, “when the Begum Aga Khan started smashing glasses with her barefoot sandals.” Melina Mercouri walked off with the best-actress award at Cannes, an Academy Award nomination, and an international reputation.

Even today most people think of Mercouri as the golden, happy-go-lucky creature who was so overpowering in Never on Sunday. The movie is still so much her trademark that whenever in the world she appeared during her eight years as minister of culture the band inevitable struck up the tune. The opposition even used it against her in the campaign for mayor. Greeks traditionally go to the polls on Sundays, so thousands of leaflets were printed saying, “Melina – Never on Sunday.” At a huge rally a few days before the vote, Mercouri, dressed in a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up, white slacks, and brand-new white U.S. Keds, threw red and white carnations to the crowd from a platform and intoned deeply, “Melina, always on Sunday,” The crowd roared.

As minister of culture during the eighties, Mercouri oversaw everything from archaeological sites to soccer stadiums. At important events in Europe she hobnobbed with her best buddy, the French minister of culture, Jack Lang, and she waged a noisy fight to have Britain ship back the Elgin Marbles, which had adorned the Parthenon before Lord Elgin finished removing them in 1812. When the roof fell in on Andreas Papandreou’s government in 1989, Mercouri had to relinquish her office, which may have been inevitable, since for the last two years she has battled a serious lung disease that has noticeably drained her. (It is currently in remission.) If there was ever a time to slow down, this was it. So friends were shocked last June when she declared her intention to become mayor, although they probably shouldn’t have been. “I hate the word ‘retire,’” Mecouri says. “I hate it.” Center stage has always been her natural milieu.

As a toddler, Melina rode beside her grandfather – who was far more important than the mayor of Athens today – in an open carriage waving to the faithful. At the age of five, knowing she would not receive the phonograph she wanted for Christmas, she looked in the mirror and conjured her first crocodile tears, one at a time. Childhood playmates recall that she could often outdo the boys in sports and climbing trees, that she was bright and quick-witted but wild and undisciplined, often cutting school and sneaking off to the movies. “She was a terrible child,” says her brother, Spiro. “Her grandfather had a colossal weakness for her, and because he was a very grand person, nobody dared to object to what Melina was doing. He spoiled her a lot.”

She was ten when she decided she wanted to act. At fourteen, rarely at school, she began a mad pursuit of a thirty-five-year-old matinee idol. Her family was appropriately scandalized, but by this time Melina’s elegant parents had divorced – her father, a ladies’ man and a member of Parliament, had run off with an actress. They were undoubtedly relieved when she eloped at seventeen with a very rich Greek in his thirties who had to quickly divorce his Romanian dancer wife to marry Melina.

“She got married so she could leave her family’s house and become an actress,” says Despo Diamantidou. “In those days in haut bourgeois families, acting was not considered a proper occupation.” Pan Characopos, Melina’s first husband, was a Cambridge-educated Anglophile who doted on Melina. Apparently never sexually compatible, they stayed married for a long time in a most unconventional style. Melina took lovers with Pan’s approval and brought them into the house. “We had a great relationship,” she says. “He was not a typical Greek man – he was very eccentric.” She spent the first years of her marriage playing at being a rich bohemian, studying acting, and presiding over a glorious salon.

“Melina was full of charm and the joy of life,” says Deni Vachliotou. “All the artists and all the politicians gathered in her house. We had wonderful conversations and wonderful parties. We were young and handsome; we had dreams and Melina taught me I could realize them,” “I was lucky,” Melina says. “I had great freedom in those years – it was very, very exciting.”

The bliss was interrupted by World War II. Greece was invaded by tGermany, and the Greeks were left to starve. Today, Melina Mercouri’s contemporaries speak of the war and the decade of civil unrest that followed as if it were yesterday. “I think our whole generation was wounded by the war,” says Despo Diamantidou. Many joined the Resistance. Melina was more practical. She took a quisling for a lover, a handsome black-marketer who kept her in furs and food and who later committed suicide because, some say, Melina threw him over after the war. She claims now that she also gave a lot of money to the Resistance. Certainly the food she got she shared with her friends – her generosity and her loyalty to her friends have never been in doubt. “During the war I was able to eat because I went to Melina’s house,” says Diamantidou. In her autobiography, I Was Born Greek, Mercouri mentions that many of her first theater audiences “hated” her for her ability to survive in style during that time. Today she defends her behavior: “I don’t like to apologize for that – I don’t want to. If I see my life today, I would say I was a young girl who just wanted to live and that’s why war is a terrible thing.”

Although Mercouri’s theater debut in 1944 was inauspicious – one critic wrote, “Too tall, too young, too blonde. Too awkward. No talent. Why doesn’t Miss Mercouri stay home where she belongs?” – she was determined to be a star. “She liked the applause, she liked to be worshiped,” says Deni Vachliotou. And she worked very hard. Eventually, her stage career began to take off, first in the classical theater, then in modern pieces. And she set out to conquer Paris.

Wearing a pink hat at lunch one day, Melina attracted the attention of French playwright Marcel Achard, who immediately wrote a part for her in his new play. The rest of the cast snubbed her, of course, as only the French can. But Colette met her and wrote her a petit poem that ended, “Elle n’a qu’a lever ses yeux et l’Acropole est la.” Tant pis for the cast. Unfortunately, those difficult French also gave her trouble with Stella. Mercouri was the supposed favorite to win the best-actress prize at Cannes, but she and the jurors celebrated so hard one night at a party given by the Soviet delegation that they arrived in no state to judge that evening’s French entry. A local scandale ensued and no best-actress prize was given in Cannes in 1955.

Mercouri and Dassin set up housekeeping together in Paris, to be near his children. What was for her an astoundingly quiet life was something quite different for him. “Julie was a little Jewish boy from the Bronx,” says his ex-agent, Alain Bernheim. “Suddenly he was turned into this jet-setty Parisian. Melina knew a lot of people – she’d been around Paris. And they were surrounded by her faithful servants – they were like slaves who catered to their every whim. You could have dinner at their apartment at any hour – two A.M., they’d cook for them.” Not surprisingly, Dassin catered to Melina’s whims as well. Though he had many chances after Never on Sunday to work on major movies with big-name stars, she would never allow it – unless she could somehow star in them too. “He made a choice and his choice was to be with Melina,” says Bernheim. “If she was in the movie, she was happy and he could be happy – if not, well, she was bigger than life.” Bernheim, who remains friends with Dassin, gave up their professional partnership when Dassin turned down a big directing job with Elizabeth Taylor. “I’ll never forget his line: ‘It’s more important for me to be with Melina than to make a movie’’’ – an attitude Dassin says he doesn’t disagree with today.

“I was very jealous when he worked with others,” says Melina. “It was very bad for his career, very bad. It’s the only remorse I have in my life, that I didn’t let him have his career. And that I brought him here.”

Although Dassin and Mercouri made nine films together, with the exception of the hit caper Topkapi in 1964, nothing came close to the success of Never on Sunday. Nor was her luck any better with directors ranging from Joseph Losey to Norman Jewison. Melina, in fact, was reprising her role from Never on Sunday on the Broadway stage in 1967 when she received the shocking news one night that the Greek government had fallen to the Colonels.

“I had a choice to shut up, but I couldn’t,” Melina says. She began to make a speech every night after her performance, telling the audience that the happy-go-lucky musical they had just seen did not accurately reflect the reality in Greece at that time. The response of the Colonels was swift. “Julie had gone to the Middle East and I was sleeping in the same room with Melina,” recalls Despo Diamantidou. “In the middle of the night an American reporter was on the phone to tell Melina she had lost her Greek citizenship.” Her response became famous: “I was born a Greek, I shall die a Greek. Colonel Pattakos was born a Fascist. He will die a Fascist.”

By her own admission, “the hedonist became Joan of Arc.” She also made the cover of Life.

If anything, Melina’s views in her youth were rightist and royalist. She began to have a more heightened political consciousness in her early theater days, and under the tutelage of Dassin drifted steadily leftward. But even today Melina Mercouri is the quintessential champagne socialist. Her baths are drawn by servants, her clothes laid out. During the mayor’s race she voted in Armani. “But it was always in the back of her mind since she was a child that at some time she would get into politics,” says Deni Vachliotou. “She got it from her grandfather.” When the moment presented itself, she was outspoken and brave.

For seven years Mercouri raged against the Colonels in country after country, rally after rally. Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Yves Montand and Simone Signoret – the crème de la crème gauche were her allies in the Resistance. In the process the temptress became a feminist. “I became great friends with women,” she says. “I had great conversations with them – they helped me a lot. I believe that the woman is a great fighter to the end,” which is obviously the way that Melina Mercouri looks at herself. Deni Vachliotou recalls that one night in Paris in 1963 she and Melina went to see the last performance of Edith Piaf, who died a few days later. The legendary chanteuse could no longer stand alone, but was held up by two men supporting her bandaged arms and hands, and on her feet were old bedroom slippers. She no longer had a voice. Nonetheless, the crowd went wild as she sang all her greatest hits, especially “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien.” Melina was spellbound. “This is how I’m going to die,” Vachliotou remembers her declaring, “standing, standing onstage.”

In 1974, when the Colonels were overthrown, Melina Mercouri returned to Greece in delirious triumph. Her overjoyed countrymen hoisted her onto their shoulders straight from the airplane. “As soon as she heard the news, she told me she wanted to go back to Greece,” says Dassin. “That meant I would have to change my life. But I thought about it overnight and I decided I would go.”

At home once again, she decided to stay in politics – “because they needed women in Parliament in Greece.” In fact, when Mercouri got elected for the first time, in 1977, representing her old Never on Sunday stomping ground, Piraeus, there were no toilet facilities for women in the Greek Parliament and there were rules against women wearing pants. Her fights to bring the patriarchs of Greece into the modern world got lots of headlines. For Jules Dassin, however, his wife’s ascending political star was something else – in his words, “a partnership dissolved.” For a few years, until he began directing plays in Greece, he was stranded professionally.

Mercouri became minister of culture in 1981 and seized on the return of the Elgin Marbles as her pet cause. No matter that just before her first press conference in the British Museum she reportedly shed tears in front of the wrong sculpture, not the Parthenon marbles at all. Never mind, because she was out to raise the world’s and Hellenic consciousness about preserving the Greeks’ heritage. She abolished museum fees for all Greeks and announced that a new Acropolis Museum would be built to house the treasures when they were returned. (Finally, in November 1990, a $100 million plan for the building was unveiled, but so far only $1.8 million has been raised to build it. “I am sure it will be easy to find money,” Mercouri insists.) But some complain that museums are often dirty and that even at the Acropolis, with its extremely serious problems of disintegration due to pollution, much more could have been done. One woman involved in its restoration reports that moneys the European Community offered for projects at the Acropolis went unspent because Mercouri’s ministry was never organized enough to institute the programs. “She was not really worse than usual, perhaps,” the woman said, “but people expected more from Melina. She made promises she couldn’t deliver.” Another archaeologist, an American, was shocked that after she personally appealed to Mercouri to preserve “an important historical site . . . an office building was erected over it instead.”

Mercouri herself would rather emphasize other things, like the many exhibitions of Greek art her brother organized for international consumption, and her success in getting the European Community to go along with her plan to have Athens made “the Cultural Capital of Europe” in 1985. As a result, some of the world’s best performing companies came, and continue to come, to Athens.

In true socialist style, Mercouri created myriad new little theaters for the provinces (while many of the more elite traditional theater companies languished or declined.) When the classics were performed at the summer festivals, Melina Mercouri was always there to lend support, taking her seat amid the crowd’s applause. Young, untried filmmakers were given the chance to make feature-length movies on government subsidies. The fact that Greek audiences stayed away in droves from these works did not disturb Melina. “I believe we have made three or four directors,” she says. “They were psychological films only for the directors, but it doesn’t matter – young cinema is good.” In contrast, Erikos Andreou, who now runs the Greek Film Center, talks about “trying to win back the Greek public by steering closer to the center,” and encouraging foreign film production in Greece, particularly by U.S. companies, which were never made to feel welcome during the years the openly anti-American Papandreou government was in power. (Mercouri’s Film Center director once told a Hollywood Reporter writer that he was more interested in the North Korean than the U.S. market.)

Greeks are notoriously hard on one another and so highly politicized that it is almost impossible to get an objective assessment of the weather let alone of anyone as controversial as Melina Mercouri and her tenure at the Ministry of Culture. The charitable view is of good intentions gone awry, and even the political opposition gives her high marks for her efforts to promote the glories of Greece outside the country. But she has serious critics.

“Because of her worldwide fame she had a chance that nobody before or after her will ever have and she blew it,” says Greek-American TV-and-film producer Renee Pappas, who is married to a Greek actor and ran a talent agency in Athens while Melina was minister. “If you wanted to go to Greece to make a film, you’d have to rely on luck. There was no office to scout locations, no office to get actors. There are dozens of English-speaking actors in Greece and nobody knows about them.” Pappas arranged for a possible “Greek Film Week” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York but needed prints of twenty Greek films. At a meeting, Mercouri assured her she would have them. “It’s eight years later and I’m still waiting for those twenty prints,” she says.

“The ministry was chaos whenever you walked into her office,” says former New York Times man Nicholas Gage. “There were always twenty people in there: she’d be on the phone trying to talk, there would be groups muttering in various corners of the room — it was just havoc.” Gage has a bone to pick with Mercouri because the movie version of Eleni, his book about his mother’s murder in Greece at the hands of Communists right after W.W. II, was not shot there. The harsh portrait of the Communists drawn in the story did not sit well with the Papandreou government, although the Ministry of Culture did O.K. the project. But “we didn’t get the kind of encouragement that made it possible to leave behind the $8 to $10 million we would have in Greece,” says Gage. As a result the film was shot in Spain.

“Listen, we were not responsible for Eleni. They asked and we gave the permission – Mr. Gage can say nothing!” Melina Mercouri responds defiantly. “I believe I was an excellent bureaucrat. I did good work on many things – I had no money, but the ministry was well organized and we had excellent relations abroad.” And what about the charges of anti-Americanism? “Ridiculous. I visited America a thousand times.” Her position is that things fell apart after she left. “Now, now it’s the shits,” she thunders. “Now there is nothing going on. You will see – now the Ministry of Culture will not even exist!”

This last year has been a tough one for Melina Mercouri. She lost the election, Greece lost the campaign she spearheaded to bring the 1996 Olympics to Athens, Jules Dassin was hospitalized. She refuses to stop smoking, and her own health is fragile. All her extraordinary life, say her closet friends, Melina Mercouri has lived in a state of anxiety – never celebrating her happiest times, but constantly worrying that such moments will not come again. “She doesn’t enjoy such things. It’s a metaphysical problem,” says Deni Vachliotou, who remembers Mercouri running down the steps of the palazzo in Cannes like Cinderella moments after the smash opening of Never on Sunday, sobbing that the triumph would not last. “For the first time in my life I was an optimist for this election and you see what happened,” Mercouri said. “It’s the only time I thought I would win.”

She sank into gloom and despair for weeks afterward. Then suddenly the black cloud, her own persona nephos, lifted. “She might run for president,” a friend predicts. At any rate, Melina Mercouri seemed to turn into that frigate in full sail again. Certainly there was no time anymore to hash over old history. She is still a member of the Greek Parliament, and the leader of the opposition in the Athens city council. “You see, I am very, very busy,” she said to me on the phone after I had returned to the U.S. “I am having a big meeting here – many people are coming to my house to talk about . . . what is the word? That dark air. Pollution!”

Original Publication: Vanity Fair – February, 1991

No Comments