Original Publication: Newsweek – June 14, 1976

Angus Deming with Elaine Shannon and Lucy Howard in Washington and Maureen Orth in New York.

For the 10,000 or more women who work on Capitol Hill, the Elizabeth Ray affair has meant a sudden barrage of jokes, smirks and indignities. One Congressional staffer wrote a check at a downtown department store last week, flashed a House identification card and was asked, “Oh can you file and type?” The fact of the matter is that a woman’s lot on the Hill is not always a happy one, but generally the least of her problems is sexual advances by the boss. Her complaints run more often to long house, dead-end careers and an abiding discrimination that reserves the best jobs for men.

They are a disparate lot. Some are idealists drawn to the Capitol with visions of helping draft important legislation. Some see a Congressional post as just a job, some as a steppingstone to careers in business or politics. Some are looking for husbands, some are excited by the power and celebrity of the men around them, and some, to be sure, fall into sexual attachments with congressmen – though rarely on the quid pro quo basis that Ray alleges. One former Capitol worker tells what it was like to be squired about town by a legislator: “There I was, an idealistic young political-science graduate from Berkeley, going to receptions at the White House, talking to ambassadors, sitting next to senators, learning the inside scoop on the news before the press even heard of it. It was heady and fun.”

But the less glamorous side of the Hill is far more typical. Senators and congressmen run their offices like personal fiefdoms – setting whatever work schedules they like – and they can be tyrannical taskmasters. Greuling hours are the rule and demands for personal errands from baby-sitting to fetching coffee and sandwiches at midnight, are not unusual. Some young staffers, especially those with college degrees and ambitions to play an influential backstage role in the work of Congress, find the frequent drudgery demeaning. Others buckle under the pace and quit.

Housing also presents problems. Because of their low salaries and the Capitol’s high cost of living, many staffers live with two or three rommmates in the high-rise apartments in Arlington, just across the Potomac. At night, some race home to dinner with family or friends. Others cruise the night spots in search of action at places like the Hawk and Dove, near Capitol Hill, or Cylde’s and Tramps in Georgetown.

The most frequently hear complaint among Capitol Hill women is that they are victims of sex discrimination. A study a year ago by the Capitol Hill Women’s Political Caucus found that women employees on Congressional staffs are paid significantly less than men performing comprable tasks. But because Capitol Hill staff members do not belong to the Civil Service – and since Congress has specifically exempted their jobs from provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – an underpaid or underutilizied employee has no legal means of appeal.

Minority: Bright and determined women do rise to positions as top-flight staff aides, but they are a minority. “Too few women have senior jobs with responsibility,” says Jane Frank, chief counsel of the Senate Judiciary subcommittee on Constitutional rights. “When a legislative job is open and there is a very competent woman available, a man is generally hired. Virtually 99.9 percent of the people I deal with here are men.”

The story of one college graduate with a history degree and a bit of campaign experience illustrates some of the problems. She expected a job doing legislative research: what she got was a post as a payroll clerk in the House finance Office at $8,500 a year. “I was crushed, absolutely crushed,” she remembers, “but I said to myself I’m willing to start at the bottom.” Two years later, she took a salary cut – to $6,500 – to work as a congressman’s receptionist. Gradually, she became the office expert in certain legislative areas, but her title remained the same and her salary increased only a bit. During the ITT affair in Chile, reporters with questions on the subject were referred to her. She was advising the congressman on votes in some fields and generally running the office – still as a receptionist. Finally, in January 1975, another congressman hired her away as a legislative assistant, making $14,000. Today she is his administrative assistant at $18,000 – but that is still much less than most AA’s make.

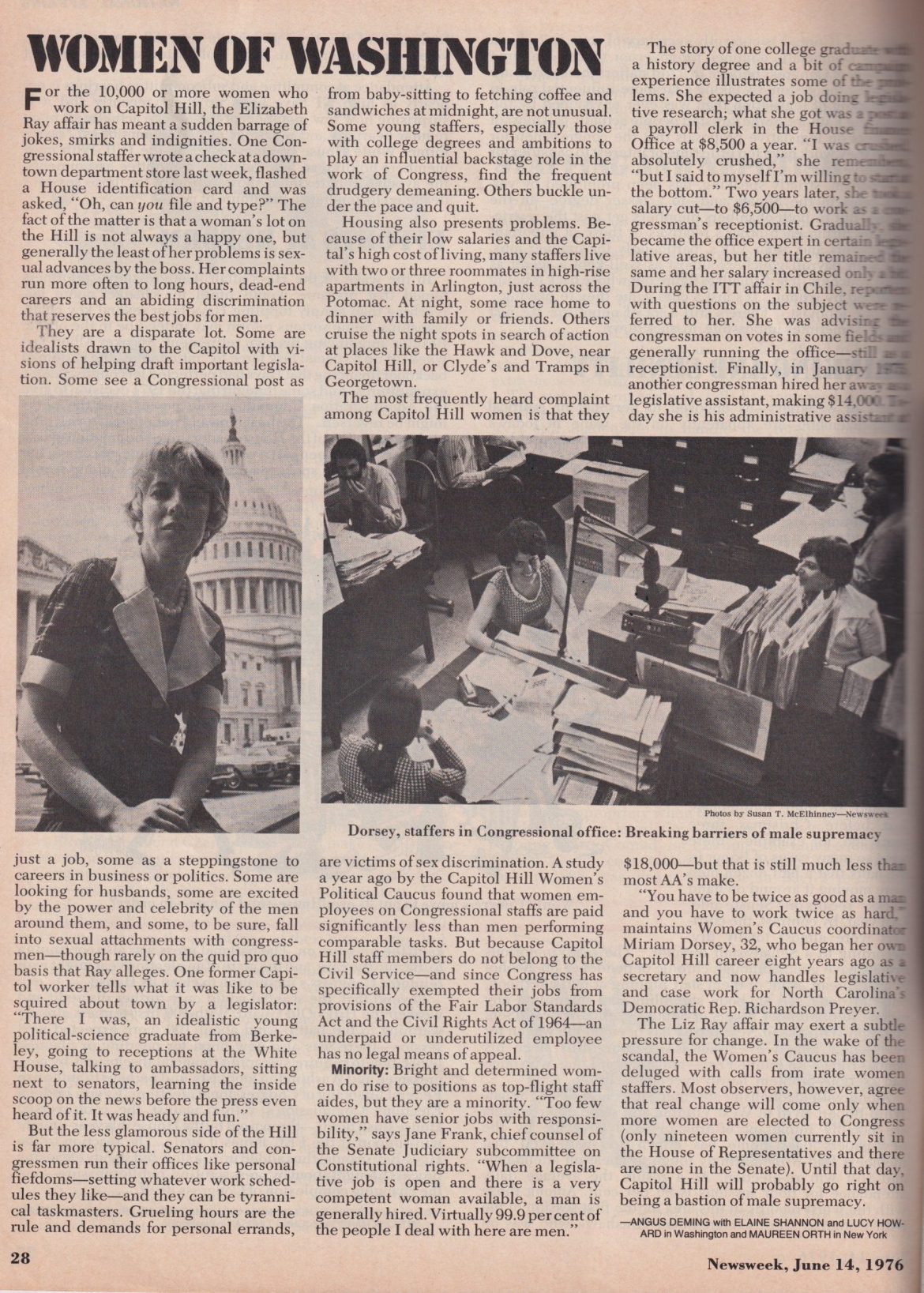

“You have to be twice as good as a man and you have to work twice as hard,” maintains Women’s Caucus coordinator Miriam Doresey, 32, who began her own Capitol Hill career eight years ago as a secretary and no handles legislative and case work for North Carolina’s Democratic Rep. Richardson Preyer.

The Liz Ray affair may exert a subtle pressure for change. In the wake of the scandal, the Women’s Caucus has been deluged with calls from irate women staffers. Most observers, however, agree that real change will come only when more women are elected to Congress (only nineteen women currently sit in the House of Representatives and there are none in the Senate). Until that day, Capitol Hill will probably go right on being a bastion of male supremacy.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.