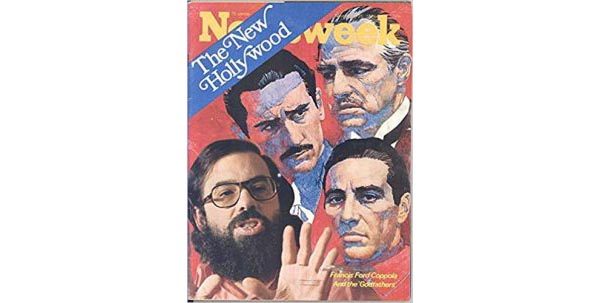

Original Publication: Newsweek – August 29, 1977.

Inside his Memphis mansion, Graceland, the king of rock ‘n’ roll lay silent in a copper coffin. Women hid tiny cameras in their bras to take one last picture as they filed past. Outside, hundreds of floral arrangements, some shaped like guitars and one like a hound dog, lined the long driveway and thousands of fans kept vigil on the tacky boulevard below in the sweltering heat. They had abandoned jobs, driven all night and flown in from abroad for one last glimpse of their idol. “Don’t faint now,” a mother warned her faltering daughter, “or I’ll just have to leave you.” A billboard down the way read “In Memoriam” and the Beef and Liberty Restaurant sign directly across the street carried the message “Rest in Peace.” But hardly anyone in Memphis could really believe that Elvis Presley was dead of a heart attack, at the age of 42.

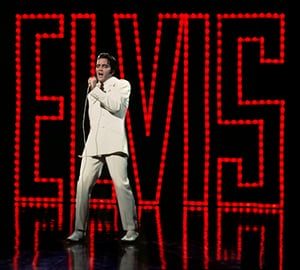

Elvis – “Elvis the Pelvis” – was more than a pop superstar. With his sleepy, sensual looks, his sexy bumps and grinds and his black-sounding voice, he not only changed the course of pop music forever, he may have created the generation gap. Rarely does an entertainer so galvanize the unstated yearnings of an age and serve as a harbinger for the decade to come as Elvis did in the mid-1950s with the first of his long parade of hits, which included “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Hound Dog” and “All Shook Up.” After his famous first appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1956, my aunt told me how foolish I was to sit screaming with joy at the spectacle of that vulgar singer on TV. It was then I knew that she and I lived in different worlds, and it was then that kids’ bedroom doors slammed all over imitate Elvis’s moves in front of the mirror. Girls gave up collecting charms for their bracelets for the forbidden charms of his 45-rpm records. Our parents hated Elvis and that was all right with us. From Elvis on, rock was rebellious.

He is death aroused the same old frenzy – and pared away the sad spectacle of recent years when Elvis had Memphis florists had to fly in 5 extra tons of flowers to fill the orders going to him. Stores all over the country were sold out of Elvis’s records, and the RCA plant in Indianapolis, which can press 250,000 albums a day, was working a 24-hour shift to catch up. Ballantine Books received what might be the largest single order in the history of publishing – for 2 million copies of “Elvis: What Happened?” an expose by three disgruntled former bodyguards. Radio stations all over the world were playing hours of Elvis music. In Japan, music critics reportedly sobbed on television as they discussed him.

In London, hundreds of Teddy boys and their tattooed girlfriends prayed alongside housewives and their babies in a special church service. In Paris, L’Humanite, the Communist Party newspaper, headlined THE ‘KING’ IS DEAD. And back in Memphis, the reckless frenzy reached tragic proportions when, hours before Elvis’s private funeral, a drunk teen-age driver ran into three people keeping vigil outside Graceland, killing two young women and critically injuring another.

When he died, Elvis had sold over 500 million records – more than any other pop star. He was born dirt poor in the small rural town of Tupelo, Miss. His father worked at odd jobs and his mother spoiled her only child as much as their meager earnings allowed. When she died, Elvis was so distraught that local lawmen would try to cheer him up by taking him on daily helicopter rides. From his mother, Elvis, who was always shy and uncomfortable around strangers, learned his lifelong habit of “Sirring” and “Ma’aming” everybody.

In 1953, after the family had moved to Memphis, Elvis, who was 18 and working as a truck driver for $41 a week, had “just an urgin'” that prompted him to pull into Sam Phillips’s Sun Records to make a record for his mamma’s birthday. Phillips was looking for a certain kind of singer. “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel,” said Phillips, “I could make a billion dollars.” That’s what he found, but Phillips eventually settled for $35,000 – which RCA paid him for his contract a year after Elvis’s first Sun single, a black rhythm-and-blues song called “That’s All Right,” became a regional hit.

The sale was engineered by Elvis’s new manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, a former carnival pitchman. Parker’s credo was “Don’t try to explain it, just sell it” – a motto his well-trained concessionaires followed last week when they hawked Elvis T shirts for $5 in front of Graceland. The Colonel, as he was called, took absolute charge of Elvis’s career and got top dollar for every job. He knew he had something special.

But Elvis didn’t. “I don’t think of it as an act,” he told an early interviewer. “I just sing. It comes out this way and that’s what I do. I never really think about it.” But he did like to be different. His tight pants and pink silk shirts were extreme at the time. He experimented for hours with his black ducktail. He wore eye shadow for his first appearance on the Grand Ole Opry and heard an official there tell him, “We don’t use nigger music at the Grand Ole Opry.” Within a few years Elvis’s style had nearly destroyed country music because every country boy wanted to sing just like Elvis – not like Webb Pierce. “He was white but he sang black,” says the noted guitarist Chet Atkins, who was assistant producer on the early records at RCA. “It wasn’t socially acceptable for white kids to buy black records at the time. Elvis filled a void.” In 1956, the Colonel parlayed Elvis’s hits into a movie career that was enhanced sentimentally when Elvis got drafted and served two years in the Army. Long before Robert Redford, Elvis was earning a million dollars per picture for the corny B movies he later scorned as “Presley travelogues.” The Colonel maintained it was his “patriotic duty to keep Elvis in the 90 per cent tax bracket”; he was loath to tamper with a successful formula, and along the way, Elvis never really grew up. “I never understood why he didn’t try to make better records or movies,” says an RCA executive. “He was like the Colonel, who felt that you don’t really need quality because you’ll always be popular.”

In the ’60s, Elvis the rock ‘n’ roll star was eclipsed by the very groups his music had spawned – the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Doors – and to most rock fans, he was nothing more than a golden oldie. For almost nine years, the Colonel kept him away from personal appearances. But in the late ’60s, he reemerged with a glittering Las Vegas engagement. In recent years, he toured sporadically, overweight and musically lethargic. But he invariably sold out sports arenas to audiences of all ages.

Offstage, Elvis increasingly isolated himself from the public. He granted no interviews. He surrounded himself with an entourage of good-buddy yes-men, the “Memphis Mafia.” He spent hours in his bedroom watching TV. For fun, he’d rent an amusement park or movie theater for himself and his friends. His generosity not just to friends but to strangers – upon whom he would sometimes lavish new Cadillacs – was legendary. But in 1972 his wife, Priscilla, whom he had married in 1967 – their daughter, Lisa Marie, is now 9 – finally grew tired of being a bird in a gilded cage and left him for her karate instructor. It was a blow he never recovered from.

Recently Elvis took to wearing a bulletproof vest during public appearances. He also collected guns. One day a few years ago in Las Vegas, when he couldn’t stand to watch Robert Goulet on television, he shot the screen out of the TV set. “He showed us the set,” said Mickey, a blond secretary who knew Elvis in Las Vegas, as she stood at the gate outside Graceland the night before his funeral last week. “He told me it was OK because the hotel always put it on his bill. Toward the end, though, he was paranoid. He kept in his Bible the police report of two guys who tried to rush him on the stage in 1973. My purse was always searched for weapons before I could go into his suite, and once when the cork of a champagne bottle was popped he ducked for cover and his bodyguards completely surrounded me.”

Were the rumors true that Elvis was hooked on pills – speed and downers? “He was so out of it sometimes he couldn’t talk,” Mickey said. “I was there one morning when he was ready to go to bed and his doctor passed out pills to everybody.” Last week former bodyguard Sonny West said another guard tried to stop Elvis from taking drugs by roughing up the boys who delivered them. “He looked Red in the eye,” West recalled, “and said,” ‘I need them. I need it.”

But it was the legend of Elvis that mattered to the fans who came to Memphis to say goodbye. “I read the bodyguards’ book and I don’t believe it,” said Margaret Carver, a 37-year-old housewife from Waldorf, Md. “Whatever’s written about him, true or false, makes no difference to me. I have no other idols.” The next day, 150 family members and friends sang “How Great Thou Art” at the private funeral service in Graceland, before the king of rock ‘n’ roll was laid to rest in the mausoleum at Forest Hill Cemetery. They heard TV evangelist Rex Humbard tell of how Elvis had invited him to Las Vegas last December. “He talked about religion,” said Humbard. “He wanted to know if Jesus would be coming back soon.”

Original Publication: Newsweek, August 1977

No Comments