Original Publication: August 30, 1976

Six years ago, a former Long Island, N.Y. debutante named Mary McFadden was running a school for native artists deep in the African bush and sleeping with a gun under her pillow. Three years later, after fleeing Rhodesia with a sizable art collection, McFadden became one of those ultra-chic fashion editors whose contacts and pedigree are much fatter than their paychecks. Today, however, she is able to support herself in the most elegant style to which she has almost always been accustomed. The Mary McFadden line of clothes and jewelry grosses $2 million a year, and its designer is a nominee this year for the Oscar of fashion – the Coty award.

New York City’s Seventh Avenue has been inundated of late with the idle rich – all eager to work their famous family monikers onto a design label. The success of commoner Diane von Fürstenberg, who married a prince and now is grossing millions dressing the bourgeoisie, started the trend. Now Gloria Vanderbilt, Susan Shiva, and Charlotte Ford have jumped in with fashion lines of their own. But of all the super-social ladies of Seventh Avenue, the 38-year-old McFadden is the most original and conceives the most striking clothes.

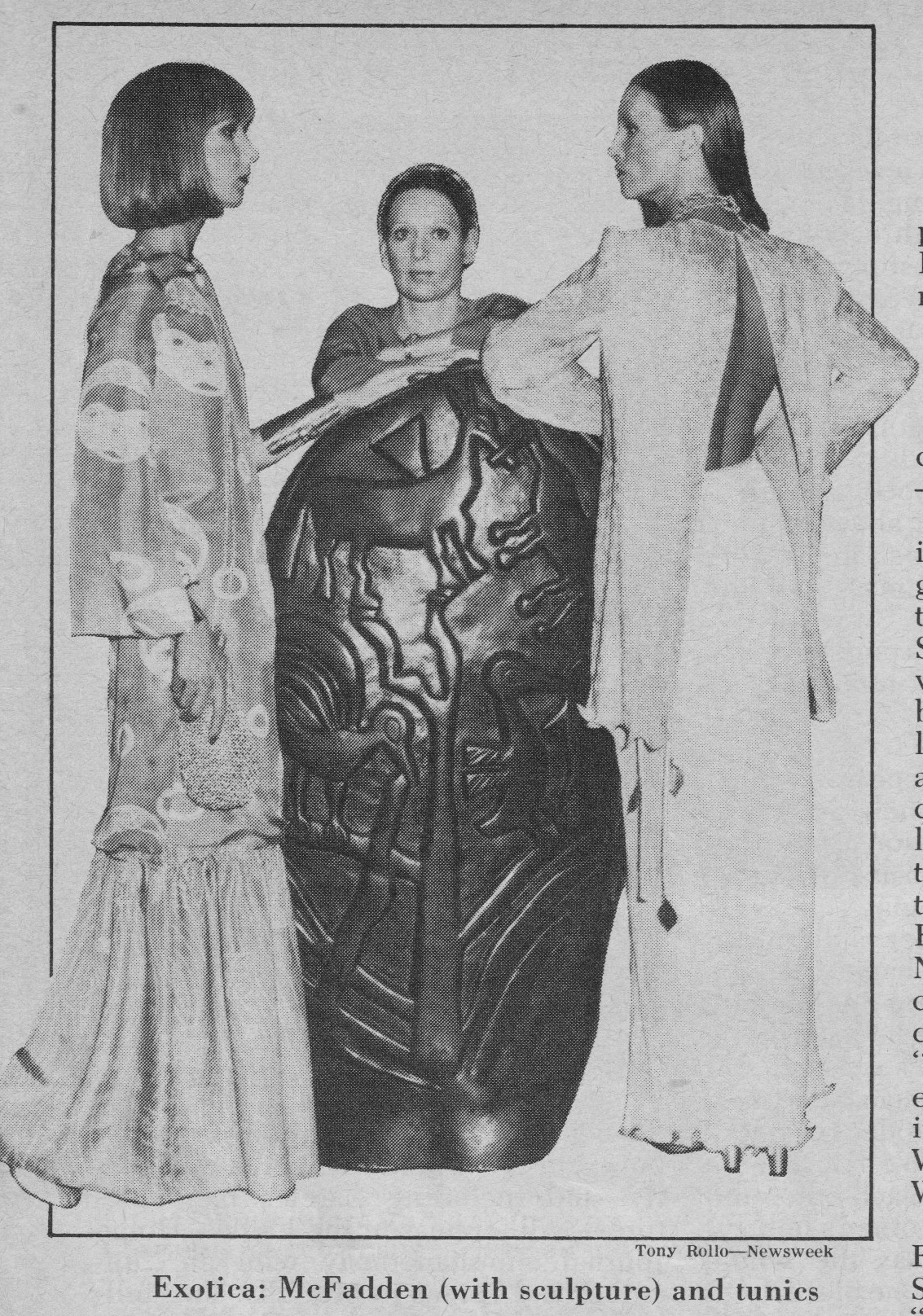

When she began designing three years ago, McFadden defied the prevailing style of clingy jersey dresses and launched the tunic-over-pants look that pervades fashion today. Her togas, evening pajamas and quilted coats, exotically hand-painted on silk, reflected her synthesis of ancient Greek, Oriental, African – even hippie tie-dye – influences.

Many of McFadden’s ideas came from photographing museum collections all over the world. She wanted women to wear her clothes (priced between $200 and $1,000) like “floating pieces of art,” with the face unencumbered by busy necklines. “The Africans say that the face is the seat of the spirit,” explains McFadden, who possesses a Nefertiti-like profile. Her creations are completely contemporary, however. “Mary McFaddens’s dresses are like modern paintings on fabric,” says June Weir, fashion editor of Women’s Wear Daily.

Not surprisingly, McFadden has little use for Saint Laurent’s recent “revolutionary” peasant collection. (Newsweek, Aug. 9). “It’s terrible,” she says. “Women have spent the last ten years paying a lot of money to get thin. I don’t think they’re going to want to cover their bodies with layers of taffeta petticoats.” McFadden would rather punctuate her featherweight designs with stark jewelry that looks like sculpture – huge belt buckles inspired by pre-Columbian idols and necklaces of brass oak leaves dipped in 18-karat gold. Her most dazzling discovery is how to make imitation diamonds out of strontium titanate, a synthetic introduced to her by some Brazilian gem traders. McFadden recently had the Hollywood glitter set wide-eyed at the 60-karat strontium titanate rock she sported on a neck chain at a party. “I didn’t admit it was fake,” she chuckles. “I told them my grandmother collected jewels.”

Socialite: She might well have. McFadden’s father was a wealthy cotton-plantation owner who died when she was 10. Her socialite mother remarried and sent her to Foxcroft School. After majoring in sociology at Columbia, McFadden headed Christian Dior’s public relations in New York. There she met her first husband, an executive for the De Beers diamond cartel based in South Africa.

In South Africa, McFadden freelanced for English and Africian publications and, after a divorce, married the director of the National Gallery of Rhodesia. In that country, she founded an artisan school for the Mashonas – a tribe that have been stone carvers since the twelfth century. The message that she wanted pupils went out on jungle drums. Before terrorist activity forced her to sell her school, McFadden employed 100 native craftsmen, exporting their sculpture to 28 countries. (Today her Mashona collection is also on sale in her Seventh Avenue showroom.) When the school ended, so did her second marriage – and McFadden hooked up with Vogue in New York.

Basement: McFadden’s big break came when Vogue decided to feature, in the magazine’s shop by mail section, a tunic she had made for herself. But first they needed a retail outlet to sell it. McFadden trotted her design over to her friend Geraldine Stutz, the president of Henri Bendel, who immediately ordered 30 pieces. McFadden quit Vogue, sold some of her art and set up shop in a basement. The line didn’t move at all until Stutz gaver her a lavish press showing. When Mrs. William Paley bought a toga, McFadden was on her way. “If you’ve seen enough of the world you are in a position to see something individual in yourself,” she says. “That enabled me to get my start in fashion.” With a little help from her friends, Mary McFadden had exchanged a silver spoon for a platinum needle.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments