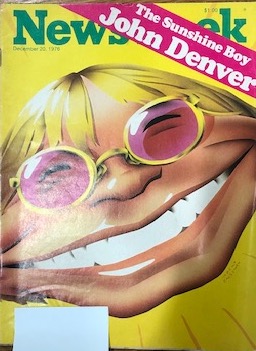

Original Publication Newsweek: December 20, 1976.

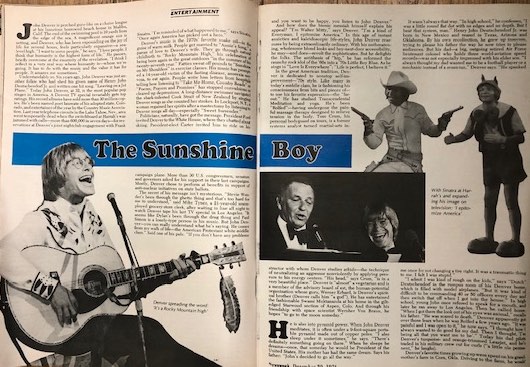

John Denver is perched guru-like on a chaise lounge at his luxurious borrowed beach house in Malibu, California. The end of the swimming pool is 10 yards from the edge of the sea. A magnificent orange sun is setting, and Denver, who has been expounding on the joy of life for several hours, feels particularly expansive – a sea-level high. “I want to serve people,” he says. “I love people. I think that humanity is the highest form of life.” He pauses, briefly overcome at the enormity of the revelation. “I think I reflect in a very real way where humanity is – where we’re going. It has to do with the music and the value it has for people. It amazes me sometimes.”

Understandably so. Six years ago, John Denver was just another folkie who had shed his given name of Henry John Deutschendorf Jr. and written one hit song, “Leaving on a Jet Plane.”

Today John Denver, at 32 is the most popular pop singer in America. A Denver TV special invariable gets top ratings. His record albums have sold more than 30 million copies. He’s been named poet laureate of his adopted state, Colorado, and entertainer of the year by the Country Music Association. Last year telephone circuits in the Lake Tahoe, Nevada, area went temporarily dead when the switchboard at Harrah’s was jammed with calls – more than 600,000 in seven days – for reservations at Denver’s joint nightclub engagement with Frank Sinatra. “I’m reminded of what happened to me,” say Sinatra. “Once again America has picked out a hero.”

Denver’s music is the 1970s’ favorite snake oil – in the guise of warm milk. People get married to “Annie’s Song,” a paean to Denver’s wife. They go through natural childbirth to “Rocky Mountain High,” his celebration of being born again in the great outdoors “in the summer of his twenty-seventh year.” Fatties sweat off pounds to “Sunshine on My Shoulder,” in exercise classes. His music has prompted a 14-year-old victim of the fasting disease, anorexia nervosa, to eat again. People write him letters from hospitals telling how listening to “Take Me Home, Country Roads” or “Poems, Prayers and Promises” has stopped convulsions or cleared up depressions. A long-distance swimmer navigated the shark-infested Cook Strait of New Zealand by singing Denver songs as she counted her strokes. In Lockport, N.Y., a woman regained her spirits after a mastectomy by listening to Denver songs all day – especially “Sweet Surrender.”

Politicians, naturally, have got the message. President Ford invited Denver to the White House, where they chatted about skiing. President-elect Carter invited him to ride on his campaign plane. More than 30 U.S. congressmen, senators and governors asked for his support in their last campaigns. Mostly, Denver chose to perform at benefits in support of anti-nuclear initiatives on state ballots.

The secret of his message isn’t mysterious. “Stevie Wonder’s been through the ghetto thing and that’s too hard for me to understand,” says Mike Tyner, a 21-year-old unemployed grocery-store clerk, after waiting in line all night to watch Denver tape his last TV special in Los Angeles. “It seems like Dylan’s been through the drug thing and Paul Simon is a lonely-tape person in his music. But John Denver – you can really understand what he’s saying. He comes from my walk of life – The American Protestant white middle class.” Said one of his pals: “If you don’t have any problems and you want to be happy, you listed to John Denver.”

And how does the bionic messiah himself explain his appeal? “I’m Walter Mitty,” says Denver. “I’m a king of Everyman. I epitomize America.” In this age of instant anxieties and kaleidoscopic life-styles, John Denver reassures by being extraordinarily ordinary. With his unthreatening, wholesome blond looks and boy-next-door accessibility, he may – and does – revolt the sophisticates. But he delights the folks. The antithesis of “hip,” he has reformed the raunchy rock idol of the ‘60s into a ‘70s Little Boy Blue. As he sings in “Love is Everywhere”: “Life is perfect, I believe it.”

In the great American tradition, Denver is dedicated to nonstop self-improvement – ‘70s style. Like many in today’s middle class, he is fashioning his consciousness from bits and pieces of – to use his favorite expression – the “farout.” He has studied Transcendental Meditation and yoga. He’s been “Rolfed” – having undergone the painful massage therapy designed to relieve tension in his body. Tom Crum, his personal bodyguard on tours, is a former systems analyst turned martial-arts instructor with whom Denver studies aikido — the technique of neutralizing an aggressor nonviolently by applying pressure to his energy centers. “His head,” says Crum, “is in a very beautiful place.” Denver is “almost” a vegetarian and is a member of the advisory board of est, the human-potential organization whose guru, Werner Erhard, is Denver’s spiritual brother (Denver calls him “a god”). He has entertained the fashionable Swami Muktananda at this home in the gilt-edged Starwood section of Aspen, Colorado. And through his friendship with space scientist Wernher Von Braun, he hopes “to go to the moon someday.”

He is also into pyramid power. When John Denver meditates, it is often under a 9-foot-square portable pyramid made out of copper poles. “I also sleep under it sometimes,” he says. “There’s definitely something going on there.” When he sleeps he dreams – once, that someday he would be President of the United States. His mother has had the same dream. Says his father: “John’s decided to go all the way.”

It wasn’t always that way. “In high school,” he confesses, “I was a little round flat dot with no edges and no depth. But I beat that system, man.” Henry John Deutschendorf Jr. was born in New Mexico and reared in Texas, Arizona and Oklahoma. By his own recollection, he grew up insecure, trying to please his father the way he now tries to please audiences. But his dad – a big outgoing retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who holds three world-aviation speed records – was not especially impressed with his elder son. “I always thought my dad wanted me to be a football player or a mechanic instead of a musician,” Denver says. “He spanked me once for not changing a tire right. It was a traumatic thing to me. I felt I was stupid.”

“I admit I was kind of rough on the kids,” says “Dutch” Deutschendorf in the rumpus room of his Denver home, which is filled with model airplanes. “But it was kind of difficult to be commanding 40 or 50 officers every day and then switch that off when I got into the house.” In high school, young John once refused to speak for a month, and later he ran away to Los Angeles. Then he called home. “When I got there the look out of his eyes was animal,” recalls his father. “He was scared to death.” Denver apparently got over those fears when he was Rolfed a few years ago. “It was painful and I was open to it,” he now says. “I thought how I always wanted to do good for my dad. Then I thought, ‘I’m being all that you want me to be’”. Today his dad pilots Denver’s turquoise – and orange-trimmed Learjet, and he’s traded in his military crew cut for curls (“a little ole permanent,” he laughs).

Denver’s favorite times growing up were spent on his grandmother’s farm in Corn, Oklahoma. Driving to the farm, he would carry the guitar his other grandmother gave him when he was 8 and listen to country music on the radio. Once there, he would play with the animals, sleep outside and gaze at the stars. He can now pinpoint the place in the heavens where he thinks he came from. “It’s near the ring nebula in Lyra,” says his friend Joe Henry, who wrote the lyrics of Denver’s song “Spirit,” which celebrates his professed celestial ancestry.

In high school he joined a rock band. “I tried to hold my guitar like Elvis did,” he says. “But when I’d look in the mirror it didn’t look right.” At Texas Tech to study architecture, he ended up spending most of his time playing the guitar. He father recalls: “I told his mother, ‘Start thinking about a name for him – he’s gonna go’.” He did – midway through his junior year. Young John headed for Los Angeles, where he took the more commercial last name of Denver at the suggestion of folk-music professionals. “I liked it because my heart longed to live in the mountains,” he says. He switched to acoustic guitar to become a folk singer because he “wanted to perform alone,” and he eventually got a gig at Ledbetter’s, a well-known club. He got his first big break when he went to New York to audition as Chad Mitchell’s replacement in the Chad Mitchell Trio. Despite a bad cold, he got the job. “He sounded dreadful,” says Milton Okun, the trio’s record producer, who has stayed on as Denver’s producer at RCA and now owns the extremely lucrative copyrights to Denver’s songs. “But I love his personality. He was full of life. His voice was not as good as Chad’s, but he lit up the room.”

In those days – the mid-60’s – Greenwich Village was in thrall to the socially conscious fold explosion ignited by Bob Dylan. “It was a foreign world to me,” says Denver. “Dylan’s songs weren’t part of my experience. I loved what he did with words, but Dylan didn’t communicate to me. I wasn’t part of – what do you call it? – the counter-culture. I was totally socially unaware.” Nonetheless, Denver’s two and a half years with the Chad Mitchell Trio were professionally invaluable and he gained the beginnings of a social conscience by meeting people like Pete Seeger and Norman Thomas. He wrote “Leaving, on a Jet Plane,” which became a No. 1 hit sung by Peter, Paul and Mary; he learned how to shape and pace a performance, and he came to realize that most audiences felt completely at home with him. He also met his business manager, Harold Thau, and – most important – his wife, Annie.

Ann Martell was a cute coed at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, when Denver spied her on a tour of colleges. For Denver it was “love at first sight.” She resisted; he pursued her; she resisted; he followed her on a ski trip to Aspen; she resisted; he proposed; they got married. He was so enthusiastic, he says, that on their honeymoon he accidentally cracked one of her ribs. Things got rougher – aggravated by Denver’s self-imposed commitment to paying off a $40,000 debt run up by the trio. “If it wasn’t for the big wedding my father gave me,” says Ann Denver, “I would have gotten divorced in a year. John and I really didn’t know each other.” “In the trio days,” says Denver, “we were overdrawn every other week and really scraping. We had one lamp we carried from room to room. It was hand to mouth and day to day and no fun.”

Denver’s constant parting from Annie were a source of friction and sadness – but they were also the inspiration for such later hits as “Goodbye Again”: “It’s something that’s inside me, not hard to understand. It’s anyone who’ll listen to me sing. And if your hours are empty now, who am I to blame, You think if I were always here our love would be the same?” “The difficult thing for us in our life,” says Denver, “has always been that what I do means as much to me as my family does. I refuse to give either one up for the other.”

In 1968, the trio dissolved and Denver went to Aspen to perform during the ski season. He felt bound for glory, “None of us believed John Denver was going to be a household word in 1968,” says Paul Lerch, a longtime Aspen friend, “but John Denver did. Even when he was poor he was an incredible optimist.” Aspen, with its majestic, relatively unspoiled setting and easy euphoria induced by clean mountain air and the availability of more expensive stimulants, was the perfect place for Denver to get high. As he explains, “I would rather get stoned than drunk, and I’ve done both. But I don’t feel that either thing is a big part of my life.”

It was also the ideal place for Denver to find his muse one in tune with a public fed up with protest and social upheaval. In Aspen, which has more than its share of rich recluses, hip hedonists, mellow “cowboys” and cocaine-snorting vegetarians, he began to write songs that celebrated uncomplicated good feelings and the joys of escaping back to nature. They were clothed in the drug metaphor of the ‘60s – “getting high” – but they were not about bad trips. “One dreary day in Minneapolis in the spring of ’70,” he recalls, “I was so down I wanted to write a feeling blue song. What I wrote was ‘Sunshine on My Shoulders’ – it came out a positive thing. I don’t know why.”

In 1971 he found his country voice with “Take Me Home, Country Roads.” It became a No. 1 hit, and it elevated Denver to stardom. That year he and Annie were able to afford a permanent move to Aspen, and in the summer Denver had his “born-again” experience – from which he emerged as an ecoaware pantheist. He was camping one night with friends, 11,000 feet high at a “secret lake” in the Rockies, when he witnessed a spectacular meteor shower. “Everyone started applauding,” Denver remembers. “For two hours we watched nature’s fireworks.” Out of that experience, he wrote the song that became his anthem:

When he first came to the mountains his life was far away,

On the road and hangin’ by a song.

But the string’s already broken and he doesn’t really care,

It keeps changin’ fast and it don’t last for long . . .

It’s a Colorado Mountain high,

I’ve seen it raining fire in the sky . . .

“Rocky Mountain High” hit big in 1973. Now, all Denver needed was to become a phenomenon.

The man who made him one, Jerry Weintraub, is – like his father – a big authoritative figure. They met in 1969, today, Weintraub is not only Denver’s best friend and the person to whom he entrusts all career decisions but, some observers say, his Svengali. “I knew immediately,” says Weintraub, “that the press would never accept John Denver. There was no glitter, no balloons. It wasn’t the Beatles or Elvis. I had a guy singing about mountains, fresh air and his wife. So I said to myself, ‘Jerry, let’s have a ground-swell hero. Let’s break him from the heartland and have the people bring him to the press.’ That was the game plan.”

Getting Denver on TV was crucial to the scheme. After he landed nothing but a series of guest shots on Merv Griffin, Denver hosted the rock show “Midnight Special.” But still the networks weren’t buying. So Weintraub sold him to the BBC. In England for six shows, Denver learned to feel at home in front of a camera. Then, in 1973, Weintraub shrewdly had an album called “John Denver’s Greatest Hits” released – even though his real hits until then added up to only two. The album sold millions; the first Denver TV special, in 1974, earned outstanding ratings, and the former “dot” was suddenly everywhere – in the hearts and minds of teeny-boppers and grandmothers alike and in the appearance of youths throughout the West and Midwest who put on granny glasses and cowboy shirts and had their hair cut Dutch-boy style.

“John exploded,” says his record producer, Milt Okun, “as all the crud of Watergate and Nixon was unfolding, when the papers, radio and TV were full of the darkest, unhumanistic things. When John writes that ‘The flowers are my sisters and my brothers,’ or ‘The Rockies are living, they never will die,” he evokes the American countryside the ways Elgar wrote about the plains of England or Mussorgsky put Russian peasant song into opera. I put him up there with Aaron Copland and ‘Appalachian Spring.’ To me, it isn’t bland. It’s great simple art.”

That art seems to be getting less simple. Formerly, it was enough for Denver at his concerts to perform in front of a backdrop movie projection showing him frolicking in the snow. Now, in his TV appearances, he has become an earnestly soft-shoeing song-and-dance man complete with chorus line. And, at least on TV, he isn’t quite so outspoken about some of his favorite causes as he used to be. For a recent appearance on the Dick Van Dyke show, Denver wanted to read a pro-Indian poem by Chief Dan George. When Weintraub objected – “it broke the continuity,” he says – Denver allowed it to be cut.

To most big-city rock critics, all of this only confirms what Weintraub knew they had always thought – that Denver is nothing but a plastic Pollyanna. Reviewing a recent Denver appearance at Madison Square Garden, one New York Times pop critic wrote: “Everything is fine, really fine. The mountains are lovely and majestic, the river is courageous . . . An ecologist and a strip miner would have been able to leave Mr. Denver’s concert with equally clear consciences.” Weintraub bristles at such attacks. “In the early days,” he says, “the press thought he was a packaged commodity. They thought he was gooey. Well, the people of this country made John Denver. I built him from the middle of the country out. John Denver is real. You pinch him and he says ouch!”

Lately, Denver has had plenty to say ouch about. Earlier this year, the city magazine of Denver, Colorado, published an article called “Rocky Mountain Hype” that blamed the pop idol for luring a tourist rush of nature-spoilers into the state and for making a killing from the selling of the wilderness. Today, it’s not uncommon to see bumper stickers in Colorado reading JOHN DENVER GO HOME. Even in tourist-oriented Aspen – where Denver has given $25,000 to the local hospital, where he frequently visits the sick, and where he has been known to help pull stalled vehicles out of snowbanks – many Coloradans wish he would simply shut up. “It’s called raping the countryside,” says a bartender in the Hotel Jerome. “Some do it with land, others do it with music.” And even that music may be suffering from overexposure. Although his TV specials and convert appearances are as successful as ever, Denver hasn’t had a hit single all year.

A year ago, his personal life also began to come apart. “I was under a lot of pressure,” says Denver. He had recently filmed a documentary of himself in Alaska. On an exhausting overseas concert tour, the Australian press had had a field day over his revelation that he had smoked hashish – which brought down the wrath of many fans. He was upset about a letter from his father, criticizing him for neglecting his younger brother. And he had just finished taping his ambitious “Rocky Mountain Christmas” TV special (which is being aired again this week). “I was starting to lose contact with Annie,” he says. “She wasn’t supporting me.” Denver flew to Switzerland to separate – and the marriage was saved only after Annie summoned an est minion for counseling.

Today, reunited with Annie, Denver says of the criticism: “It doesn’t bother me. My only concern is that nothing I say get in the way of what my life – I mean music – does for people. It seems to me I’m being more effective in achieving the revolutionary goal of transforming the collective conscience of the world in what I do than politicians are. I’m making a contribution to people’s lives.”

As a self-appointed messiah, Denver divides the world between “people who are in touch with themselves” and those who are not. By the same token, he views his music as far more than mere entertainment. He sees it as a tool for coping, the gospel of a new secular religion whose godhead is one’s own head – “really together.” His gurus are Werner Erhard and Muktananda. “They’re running the universe,” he says. “They’re gods and they know it. Right under them I put Dick Gregory, Jacques Cousteau, Wernher Von Braun, Stevie Wonder, myself and Jerry Weintraub. Oh, yes, and Richard Bach – the one who wrote ‘Jonathan Livingston Seagull.’ He’s far out.” Jimmy Carter doesn’t quite make it. “Mr. Carter has a vision,” Denver allows, “but it is a limited one. “When I see Carter,” says Milt Okun, “I think, here’s a guy taking John’s thing making it into a bit.”

Denver and Annie studied est together. “It is the single most important experience of my life,” he says. She says: “It taught me not to resent John’s success.” Erhard declares: “John is our most effective celebrity.” Denver has sent many of his close friends and colleagues through est – even his parents, who were personally trained by Erhard but who didn’t in the est jargon, “get it.” “I realize these kids are seeking something,” says Dutch Deustchendorf. “But I put Werner Erhard right up there with that Korean Reverend – what’s his name? Moon. At least Jimmy Carter has Jesus. That’s always been around. But Erhard has nothing to hang it on.”

Denver’s conversation is heavily loaded with phrases and notions drawn from the consciousness movement. He admires Annie’s recent journey to the chic California fat farm, The Golden Door, as a great means of “centering herself.” He also believes that “everyone creates his own situation, even unborn babies in choosing their parents.” While trying to adopt a child two and a half years ago, Denver had a dream that he and Annie would become parents of a “little brown baby.” Soon after, they were given a Cherokee boy whom they named Zachary. “I knew he had chosen us,” says Denver. Now he’s praying to the spirit of the baby girl they hope to adopt soon, Anna Kate. When pressed for a logical explanation, Denver says: “I don’t know why. I know what is. Werner says understanding is the booby prize.”

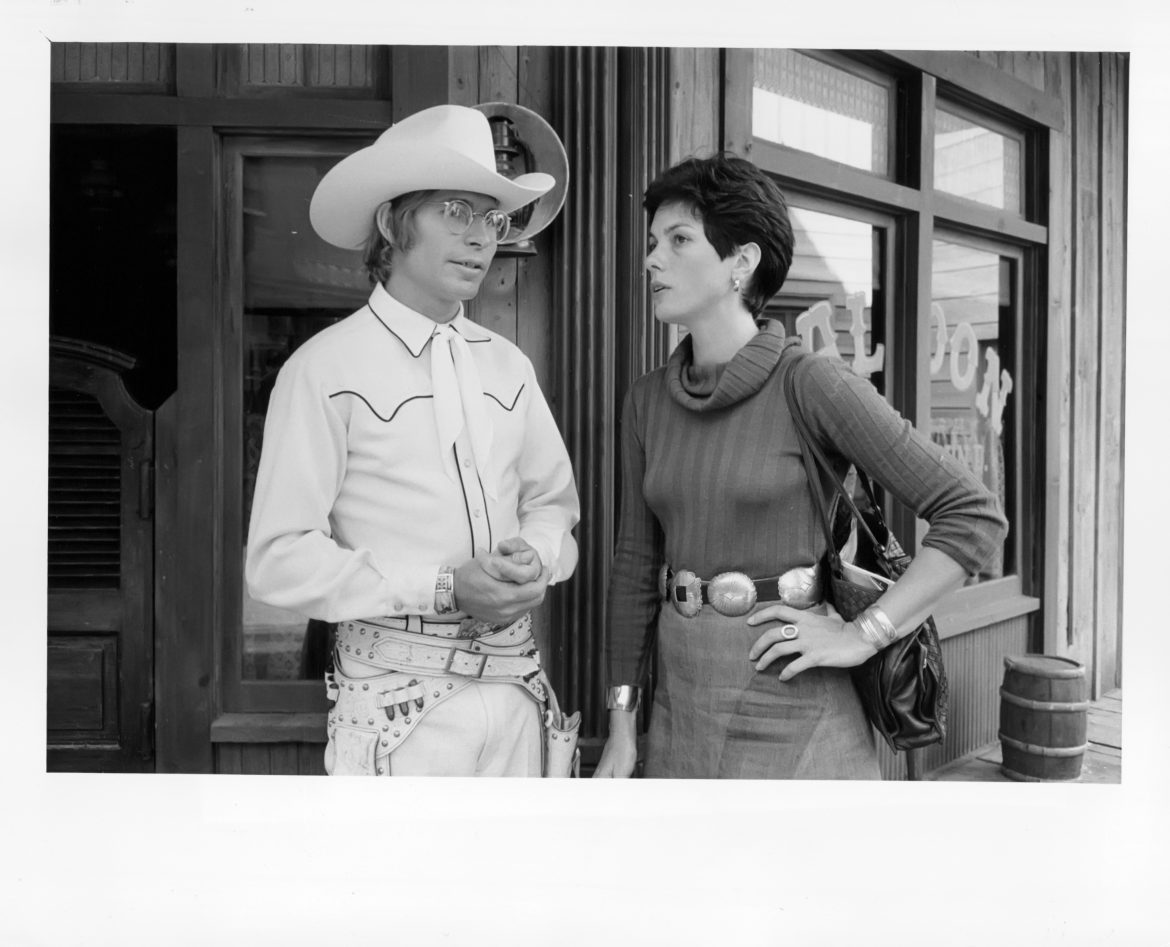

“I dream too,” says Weintraub soberly, and at the moment he foresees that Denver will be “very big in movies.” He is already set to star opposite George Burns in a comedy, “Oh God,” to be directed by Carl Reiner. “I play an assistant grocery-store manager and God grants me an interview,” says Denver. “He’s picked somebody to tell the world He still cares and it’s up to us to make it work.”

Back on his mountainside in Aspen, John Denver keeps to a close-knit group of friends. He works on his vegetable garden with the sensitive cowboy poet Joe Henry. He and Annie took in Claudine Longet on the night she shot her lover, ski pro Spider Sabich. He talks by phone to his faithful secretary, Peggy Johnston, who, in her home in the Aspen flats, performs her nightly ritual of signing his name to glossy photos of John Denver white she watches “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.” But no outsider can get very close to Denver’s “sweet Rocky Mountain paradise.” Starwood is sealed off by a big gate and a guard who, when he’s telling the curious to go away, hands out those glossy photos and a short biography of Starwood’s biggest star. And why not? “I can do anything,” says John Denver. “One of these days I’ll be so complete I won’t be a human. I’ll be a god.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.