Original Publication – Newsweek, April 25, 1977

“Our goal is to conglomeratize the world. We try to maximize everything vertically and horizontally. It’s a natural flow of men reaping the harvest to the fullest extent. These are vast plans with the sweep of empire” – Sam Weisbord, president of the William Morris theatrical agency.

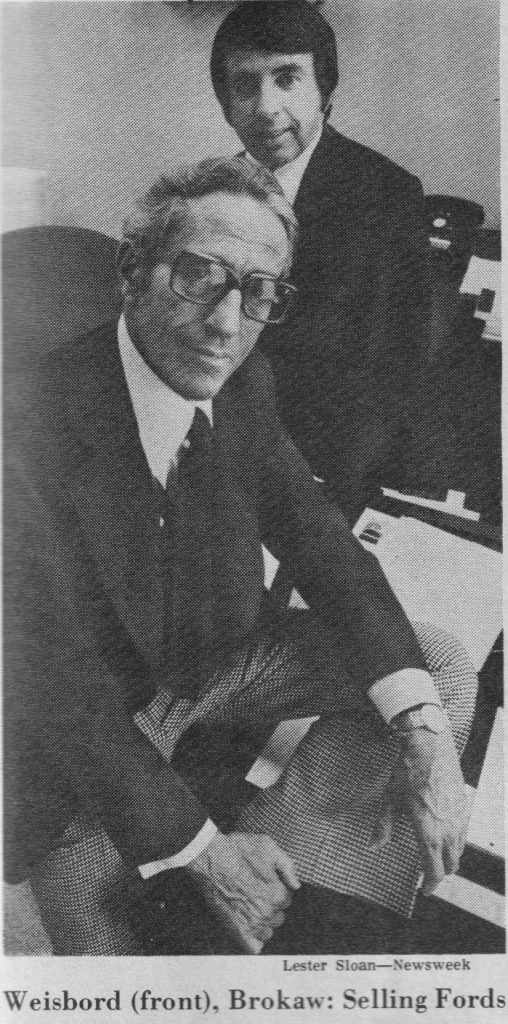

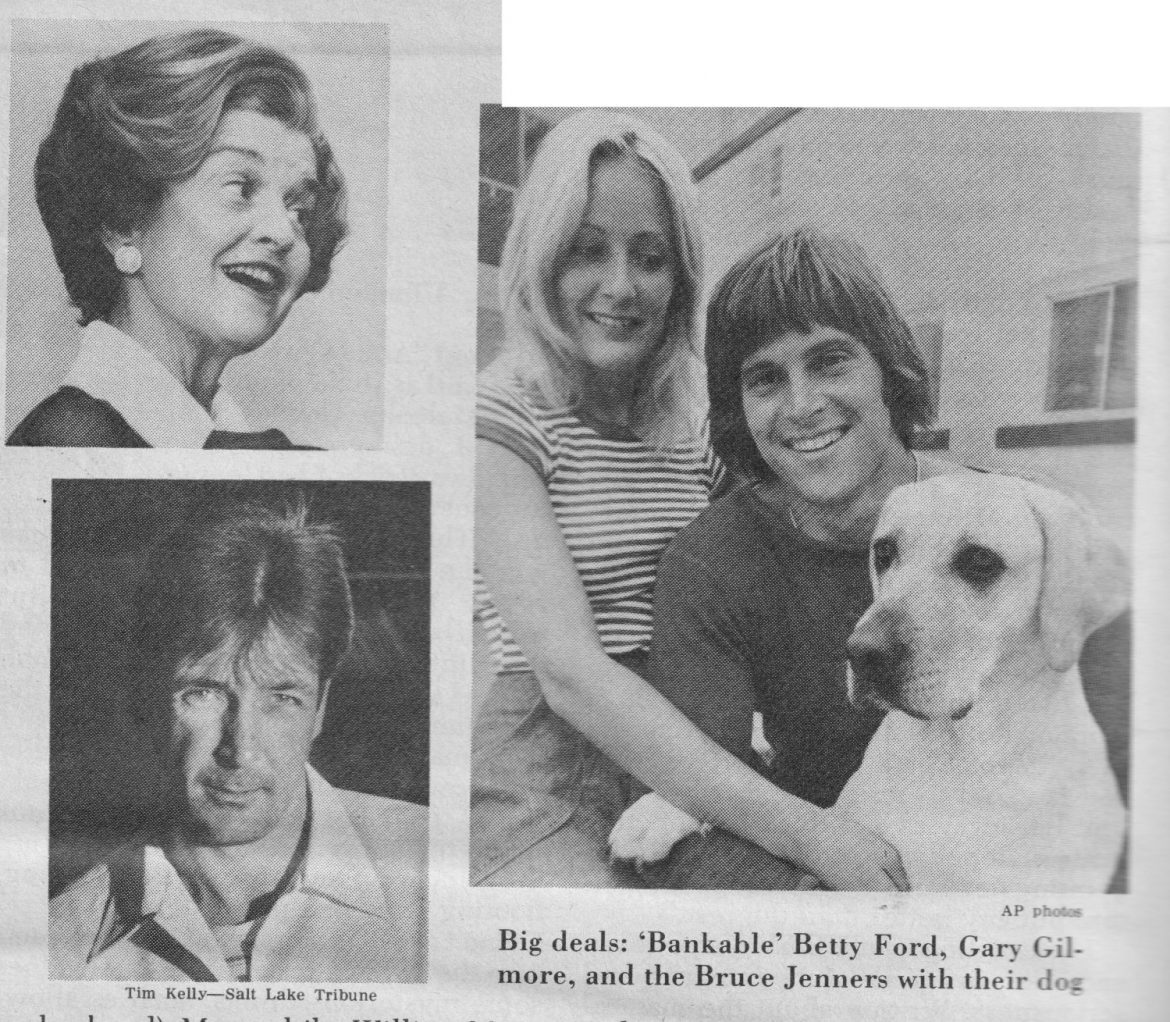

Things are humming along nicely at William Morris this year. Norman Brokaw, a vice president of the giant agency, recently put the finishing touches on nine separate book, TV and employment deals for Gerald R. Ford and his family (Betty Ford was reportedly considered even more “bankable” than her husband.) Meanwhile, William Morris’s biggest rival agency, International Creative Management, has been busy packaging another new millionaire, Henry Kissinger, who is planning his memoirs and contemplating his future as a commentator on NBC. ICM fared less well last month when one of its agents briefly but unsuccessfully canvassed publishers to see if there was any interest in a book about the Hanafi Muslim terrorism in Washington, D.C. – even as the lives of 134 hostages were being bargained for. “The value dropped because only one person died,” explains Daniel Okrent, editor-in-chief at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Today there’s no business like the agent business, in a society where gossip and disaster pass for biography and history and where, in Weisbord’s words, “everything is of interest and there’s nothing that cannot be utilized.” Thus, former Sen. Sam Ervin of Watergate fame is now promoting American Express on TV. Free-lance agent Lawrence Schiller has won “the rights” to market Gary Gilmore’s death. Cosmopolitan magazine’s editor Helen Gurley Brown, has asked Patty Hearst to write an article on the subject “everything a Cosmo girl needs to know about not burning up in a fire.” Everybody who wants to make it has to have an agent – from the President’s brother, Billy Carter, to decathlon champion Bruce Jenner’s dog. Once, the lines between show business, politics, journalism, sports and the news media were sharply drawn. Today, it’s getting hard to tell one field from another.

For Brokaw, 50, who began in the William Morris mail room at 15, the Ford deals were his finest hour. “An agent,” says the Gucci-clad superagent from behind his Gucci desk set, “is someone who can mount the canvas and paint the picture.” “Four hundred years of experience went into making that deal,” declares Weisbord, who’s been with the company for 50 years. “It’s the highest form of agentry there is.”

At the same time Brokaw was finishing with the Ford deals, Weisbord was landing another new client – the former deputy director of the CIA, Lt. Gen Vernon A. Walters. Walters’s experiences as interpreter for three presidents not only landed him a fat book deal but assured him that whatever he writes can be spun off profitably by his new agents. With its tentacles reaching into every aspect of show business, it’s not far-fetched imagining William Morris arranging a paperback sale, a movie sale, perhaps a novelization of the screenplay, a TV special or mini-series, a soundtrack album and appearances for Walters on news programs.

In sports as well, agents have taken on vast new power ever since the courts gave professional players the right to negotiate contracts for themselves on the open market. During last fall’s baseball draft, one of the top sports agents, Jerry Kapstein, put ten major-leaguers on the block and got them deals worth $16 million in all. “Not one owner,” says Kapstein somewhat questionably, “felt that he had paid an excessive price.”

Package: On many deals the more powerful agencies are making large profits by getting 10 per cent of several of their clients’ salaries at once. “Big agencies always try to put you into a situation where you have to accept at least two of their clients on a deal,” says one film-studio executive. “Today they try to package either the writer and an actor or the producer and director.” “If you’ve got a movie with a talent budget of $2 million,” says an agent, “a good agency should be able to commission $1.7 million of that.” ICM represents 40 per cent of the profits of the film “Bound for Glory,” for example, and William Morris also conveniently represents the two writers who will “assist” on the Fords’ memoirs.

It’s a far cry from the days when an agent simply earned his 10 per cent by negotiating a five- to seven-year contract at a major film studio or the sale of a manuscript for a hard-cover book. In Hollywood, the old studio system has been replaced by an ever-changing cast of executives who are mostly ex-agents responsible to the boards of directors of huge conglomerates – who seem to care only about increasing their earnings per share per quarter. “If we get lucky,” says Jennings Lang, an ex-agent and vice president of Universal Pictures, “we’ll get more people to spend more money to see fewer movies than ever before.”

The result is the blockbuster mentality that prevails today in entertainment, sports, communication and publishing – where the big bucks go for fewer deals that promise maximum returns. These deals are then hyped to the public as special, not-to-be-missed “events.” It is a small-is-not-beautiful strategy that plays into the hands – and pockets – of the agents and those few genuine superstars who can name their own price. Marlon Brando, for one, is getting $3 million for three weeks’ work in “Superman” (he plays Superman’s father.)

In this high-pitched atmosphere, a corporate panic has set in. With the stakes so high, the best way is the safe way: two of Hollywood’s richest independent producers, Richard Zanuck and David Brown, are currently working on sequels to their biggest bonanza, “Jaws,” and to the world’s most cherished movie, “Gone With the Wind.” And since nobody can pre-sell a story better than a Walter Cronkite, a Barbara Walters, a John Chancellor or the Associated Press, producers and publishers are increasingly snapping up news headlines for instant dramatization.

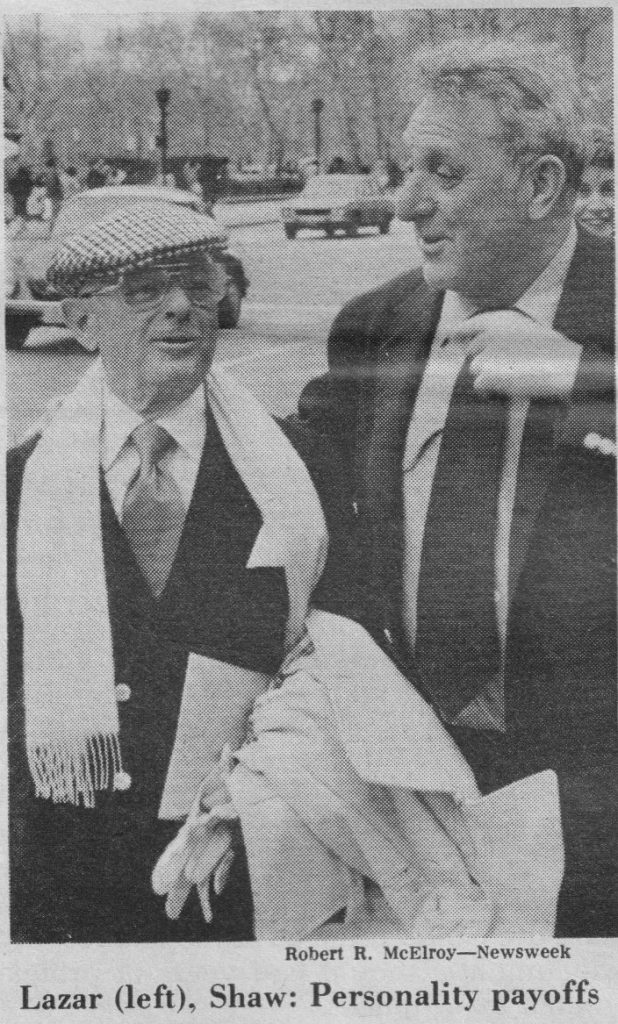

Jackpots: It doesn’t have to be a Patty Hearst trial to sell. “Anybody can make an easy deal,” says veteran literary agent Irving (Swifty) Lazar, “but only a true agent can sell a dog.” Lazar, who represents Richard Nixon, has recenlty taken fine advantage of the new influx of capital into the publishing world ushered in by conglomerate take-overs of independent houses. In the last six weeks along, he’s sold $7 million worth of books. They range from celebrity memoirs (Tony Curtis, Lauren Bacall) to romans a clef by gossip columnists (Joyce Haber, Eugenia Sheppard) to new novels by Elia Kazan and Irwin Shaw, who hit the jackpot with TV’s spinoff of “Rich Man, Poor Man” into a mini-series – a brainchild of Swifty’s. “Television is such an intimate medium,” says Lazar, “that it’s caused people who want to read more about personalities, who interests them – whether their stories are well written or not.” “Our society is becoming like People magazine,” says Joni Evans, associate publisher of Simon and Schuster. “The entire world has become a gossip sheet.”

It’s inevitable that, with so much money and effort going to the big books and the big stars, lesser creative lights are being left behind. “So far it’s the ‘so-so’ first novelist and serious nonfiction writer who is losing out,” says lawyer-agent Morton Janklow, who recently approved the paperback-rights sale of William Safire’s first novel for $1,375,000. “Before this kind of author wouldn’t get much of an advance, but he’d write for a living and develop. This is a serious loss,” “We have people earning $250,000 a book thinking they’re failures,” says Evans.

Four Paragraphs: At the same time, caution and care are becoming outmoded. “We are now being asked to make a decision not on a manuscript but on an outline, even a conversation,” says Okrent at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. “Some proposals today are even being written by the agent. So I buy something off of four paragraphs when prudently I should see two chapters. But if I want to compete I’ve got to play the game.”

Even though the agents are busier and in many cases, richer than ever before, they’re not necessarily happier. “Nobody is telling the studios to pay those higher star salaries,” complains ICM Hollywood agent Sue Mengers, who represents Barbra Streisand and Tatum O’Neal. “Sometimes they offer more than I’d have asked. The small number of films being produced today cannot sustain an industry. It’s a harder sell all around.” “People in our industry are scared to death of originality,” says Freddie Fields, an agent-turned-producer. “When you don’t have confidence, you oversell.” So far, the Israeli raid on Entebbe has been sold, packaged and spun off into a dozen different show-biz projects. In the agent society, it’s not so much what the public wants that mattters as how many deals can be made.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments