Original Publication: New York Magazine – February 11, 1980.

Irving Azoff is throwing chocolates out of the window of his speeding limousine, just wafting them right out there onto the L.A. freeway after a single bite. Irving figures he’s got a right. He may stand barely five feet tall, but Irving Azoff is nonetheless “very heavy.” At 31, he’s already gone from being one of rock’s most powerful managers to producing movies which just happen to feature sound tracks by his all-star clients. Irving Azoff is the manager of the Eagles, Steely Dan, Boz Scaggs, Jimmy Buffett—power acts that keep millions rolling in like Malibu waves. Azoff is also producing John Travolta’s new movie, Urban Cowboy, with Bob Evans. His acts refer to him as “His Shortness.” Irving Azoff is a legend in his own height zone.

“Jerry called me three times today,” Irving says, tossing a bonbon. “He’s very nervous.”

Jerry, of course, is also Junior Brown, governor of California, the dark-horse Democratic presidential aspirant who would naturally gravitate towards Azoff since he thinks small is beautiful. Brown’s campaign slogan is also very Zen and Out There for rockers—far out there: “Protect the earth, serve the people, explore the universe.” Yet, at first glance, the stiff and spare Brown, who grew up chanting Gregorian instead of doo wop, seems a most unlikely rock fan. But never mind.

Brown’s campaign coffers will be enriched by about $300,000 in the next 36 hours, this weekend before Christmas, because of two rock concerts, one in San Diego and one in Las Vegas. Performing will be Brown’s girl friend, Linda Ronstadt; Azoff’s clients, the Eagles’; Chicago, Jeff Wald’s act. These rock concerts will be among the most profitable ever staged for a politician. So it’s not so strange that Jerry Brown stalks recording studios the way John Connally woos the Petroleum Club.

“Does the governor call you a lot?” I ask Azoff.

Irving’s bushy little eyebrows shoot straight to the roof of the limo.

“I can’t get rid of him.”

Brown is hardly alone in his pursuit. Jimmy Carter has gone after Nashville and the country stars. One of Azoff’s other clients, Jimmy Buffett, will support Carter. Ted Kennedy is trying to woo Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond. The Republicans are perceived by the music business as being so square that the usually have to make do with Pat Boone or Steve and Edie.

Raising money through rock concerts though, has a double appeal. Under 1974 campaign-financing laws, the $1,000 limit on individual contributions does not apply to a rock star, who can donate his services for free and raise hundreds of thousands of dollars. Moreover, part of the concert take is also eligible for federal matching funds, provided the candidate can raise enough small contributions elsewhere. In effect, a $20 ticket for one of these concerts raises $29 for Brown.

“The justification for doing this is a means of giving something back,” said Azoff. “The reason I can condone us doing this is that there’s not one thing I want. Not one. What could a rock ‘n’ roller need from this system?”

I look at Azoff’s cashmere coat and start to tally his pubescent millions. “Good question, Irving.”

“The media’s so cynical,” said Eagles’ drummer Don Henley. “It just doesn’t believe anyone has good intentions. I have nothing to gain from this except I plan to have children and grandchildren, and I would like them to have a nice world to live in. Sometimes I wonder why I give a shit, but I’m sorry. I do.”

At first the Eagles leaned toward Kennedy. “We did a little comparative political shopping,” said Eagles’ guitarist, Don Felder. “We talked to Kennedy, and Jerry’s been real intimate with us.” They also sought the advice of those in the know. “Our bodyguard, Smokey,” says Felder, “used to be in security in the White House. He taught us how to play political pool, how certain things go down.”

But as in so much of his campaign, Kennedy blew it. First, Steve Smith, Kennedy’s brother-in-law, did not personally show up at lunch with Azoff in Boston, but sent an aide instead. Then John Tunney, ex-California senator and Kennedy’s old chum, decided that rock manager and film producer Jerry Weintraub, Irving’s friendly rival, would be handling entertainment for Kennedy in California, despite the fact that Weintraub is on George Bush’s national steering committee. But the final blow came one day last fall. Wearing sport jackets over their jeans, the Eagles visited Kennedy in his Washington office, calling on the senator in their capacity as an anti-nuclear lobby. Kennedy spent a half hour with the band, carefully outlining his stand on nuclear energy. A TV crew was staked outside his office just in case the Eagles decided to walk out and declare for Kennedy on the spot. But the very next day, when Kennedy was in the same Nashville hotel as the Eagles, only one floor away, he really ticked the rock stars off. He didn’t even call them! “He put so much space between us,” says Felder. “There was no contact at all.”

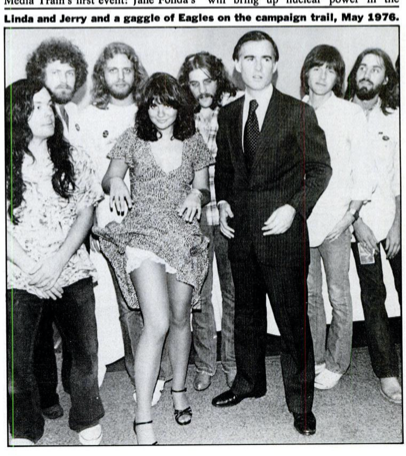

Jerry Brown flew in to fill the breach. He joined the Eagles tour in Atlanta a few days after Kennedy spaced himself out of the Eagle’s support, “Just to hang out with the band.” Now the Eagles are performing for Brown, who drops by their homes with Linda Ronstadt, visits them at their recording studio, invites them to dinner in Sacramento, and gives them books they might find interesting on the energy problem. And now Irving just shrugs at the question of which candidate has won his multi-millionaire, mixed-media heart. “I’m unimpressed with every politician,” say Irving Azoff. “Politicians are just show-biz people who are supposed to have a conscience.”

The limo pulled into Los Angeles’s Union Station in time for us to board the “Media Train” in what the Brown campaign termed “a transportation event.” The various media were out in full force for the two-and-a-half-hour train ride. ABC, NBC, CBS, the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, the Sacramento Bee, Esquire, 20/20—they were all there to watch the governor and Jane Fonda, Helen Reddy and Jeff Wald, the Wald’s six-foot-six bodyguard, Big John, plus 182 contributors who paid $150 each to take the train to San Diego, where the first of the two benefit concerts for Brown would be held. Linda Ronstadt was nowhere in sight. The Eagles, who eschewed the train, took limos down, and Chicago’s eight members chartered a Lear jet for the twenty-minute plane trip from L.A., at a cost of approximately $1,500. All these expenses would automatically be deducted from the final gross.

Yet before he ever boarded the train, Jerry Brown started getting the kind of press and television coverage that a candidate such as he, with a faltering campaign and only limited funds, dreams of. As he stepped onto the train platform, flanked by Jane Fonda and Helen Reddy, Jerry Brown was an instant media darling.

On the train, Brown looked impeccable in his usual three-piece gray suit as he slid into a seat next to Helen Reddy. “Having rock concerts is just one way of raising money for a campaign,” he said. “It doesn’t compare with the oil lobby or…” But before he could go on, he was interrupted by the Media Train’s first event: Jane Fonda’s surprise birthday party. Jane Fonda, now 42, clapped her hands and blew out the candles. “You know what I’m wishing?” she asked. “I can’t tell or it won’t come true. But you know.”

One seat up, Fonda’s little son Troy was happily playing with a war toy—a small metal firebomber with bright-orange flames coming from its jet engines. Across the aisle from Fonda sat a retired army colonel from the Pentagon, one of the $150 guests. He fingered a small brown Leatherette autograph book, glanced towards Jane Fonda, and said, “I sure hope she’ll let me have her autograph.”

Other train riders included a group of militant gay males sporting ERA t-shirts, a newly appointed Beverly Hills municipal judge—she was wearing jeans and a peasant blouse—and a recording executive who had dreamed up another “transportation event: a three-day steamship cruise from San Francisco to Baja California for 300 at $1,000 per person. He had investigated and found the kind of helicopter that could be attached to the top of the ship so “Jerry can fly out for a day and visit.”

“The way I figure it,” Tom Hayden was telling Newsweek, “Jerry for sure will bring up nuclear power in the Iowa debate; he could be a broker at the convention if there’s a deadlock between Carter and Kennedy; he’s got an outside chance for the nomination and a very good shot for ’84. So it’s a no-lose proposition.”

“As a citizen who serves on the California Parks and Recreation Commission,” says Helen Reddy from her seat nearby, “I have learned that a private, rich individual can accomplish more than anyone in government. For example, I want fruit trees in the parks, which is against their policy. Well, you can lobby legislators for years on end and accomplish absolutely nothing, or you can just donate the trees, which I did, and they have to accept them.”

“You mean you can just use your economic advantage to take things into you own hands and accomplish more without the political process?” I asked.

“Uh-huh. You get it done quicker. I believe in the individual.”

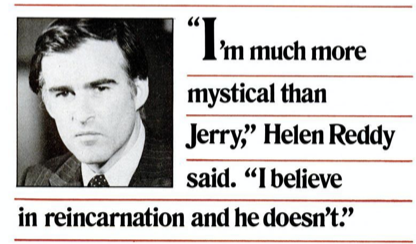

Helen Reddy took a bite of birthday cake. “Actually, I’d much rather discuss religion with Jerry.”

“What do you discuss?”

“I’m much more mystical than he is,” Helen Reddy said. “I believe in reincarnation and he doesn’t.”

I excused myself to go look for the candidate. Jerry Brown was standing in the club car with Azoff. His eyes were restless and questioning.

“Rock ‘n’ rollers are doing so much for you,” I said. “What are you doing for them?”

“I’m trying to protect the earth and explore the universe,” Brown answered evenly.

“But isn’t that your same old bull?”

“No, it’s not,” Brown protested. “They’re future ideas. People in music often sense the future before others. The poetry of an age often prefigures the coming decade. In much of the music of the seventies, you will find out what happens in the eighties.”

“Like which songs?”

“Don’t tow me down that path. I’m not going to get into that.”

“Hey, Jerry,” Irving said, “have you learned the lyrics to ‘Life in the Fast Lane’ yet? They’re going to make you sing it up onstage with them tonight.” The governor did not reply.

Then Jeff Wald, wearing a green suit and a turtleneck, strode up.

Wald, who was a delegate to the ’76 Democratic convention, says he’s supporting Jerry Brown because he wants to see “a sane society.” “Jerry is the only candidate who sees the interconnection between our energy policy and our economy and our environment and everything else,” Wald says. He bemoans the bailout of Chrysler and continues, “Our technology, our products aren’t as good anymore. Helen and I have five cars; all of them are foreign. We have nineteen TV sets; eighteen are foreign and the American one breaks down all the time. We need someone addressing these issues.”

When it was time to get off the train, the governor asked Irving and Jeff Wald to join him in his California highway-patrol car—the only Media Train passengers so honored. The state policeman guarding Brown was wearing an Yves Saint Laurent blazer.

The vast San Diego Sports Arena was not quite sold out, but the scale of the event was impressive. And the kids who paid their $20 knew why they were there. “I came for the music,” said eighteen-year-old Karen Magnum. “As far as the entertainers go, I could care who they support.” “I wouldn’t care if this had been for Reagan or Connally,” said Jim Scarfo, 25. “I’d still come.”

After Chicago played the first set, Jerry Brown held a chaotic press conference surrounded by several still-sweating members of the band sporting towels around their necks. The press crowded in, standing on tables, straining to hear. So did the fans. Jerry Brown tried to proffer a few points of difference between himself and Jimmy Carter on Iran. He was interrupted by drunken rock fans. Chicago’s Bobby Lamm told the media that Jerry Brown was the only candidate he could relate to. The drunks wanted to know what Linda was wearing. She was wearing a tight purple velvet sheath whose straps kept falling down and red satin stiletto heels. Most of the time she stayed closeted in her dressing room, and at the end of her set she came offstage without introducing Jerry Brown, though he was hovering on the sidelines apparently expecting her to.

“Irving, when are you going to let Jerry Brown onstage?” I asked. The governor was once again hopefully pacing the stage platform. It was nearly midnight.

“After the Eagles do ‘Take It Easy’ [their third encore number], I’ll let him do this,” Azoff said as he flicked a feeble little wave.

“Aren’t you going to let him talk?”

“Of course not.”

Brown saw me watching him pace, awaiting his call. He came toward me nervously.

“My T-shirts sold out at nine o’clock!” he boasted.

And so they had—1,500 brown ones, sporting The Slogan in pink: “Protect the earth, serve the people, explore the universe. Jerry Brown, 1980.”

When Brown was finally introduced to the crowd by the Eagles as “a man of the future,” it was 1 A.M., and he was booed, not by many, but booed nonetheless. They were in no mood for political speeches.

When the Eagles finished their last encore, they rushed to the backstage area of the huge arena, where their usual six separate limousines were waiting, motors running—one for each Eagle and one for Irving. Jerry Brown shared Eagle Glenn Frey’s limousine back to Los Angeles, but the next night in Las Vegas, the Eagles refused to introduce him at all. Irving broke the news to him late in the evening and told him it would be better if he left before the Eagles finished their set. Obviously hurt, Brown complied and flew back to Los Angeles on a commercial airliner. He had come on a private rock ‘n’ roll plane. And so the governor of California was not even allowed to appear publicly at one of the most successful fund raisers of his career. It was okay if Jerry Brown took the money, but the rock stars did not choose to have a politician invade their space.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.