Original Publication – Glamour, June 1988 pg. 266

One day last winter in the tiny town of Sumter, South Carolina, the local Republican introducing Elizabeth Dole began by enumerating strong political women: “Nancy Reagan, the Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher and Jeane Kirkpatrick. Without further ado I give you the next Pres—I mean the next First Lady, Elizabeth Dole.”

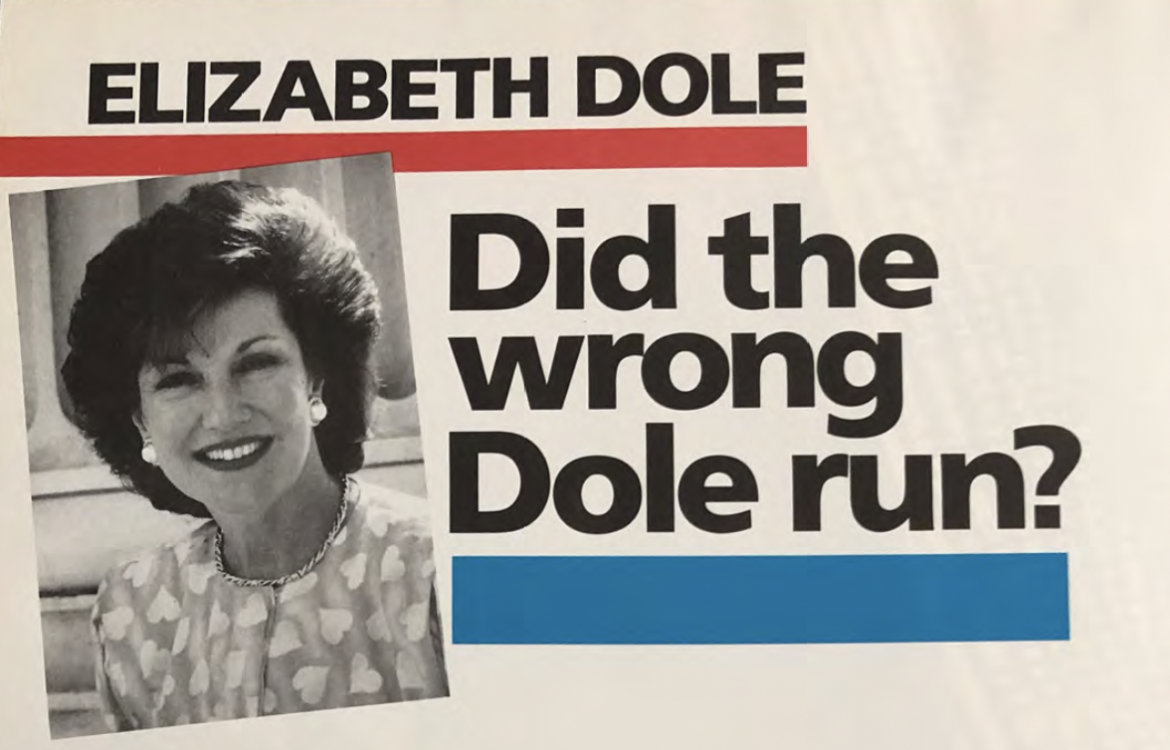

Amid laughter and applause, the immaculately turned out, youthful-looking fifty-one-year-old Harvard Law graduate with electrifying presence stepped forward. This wasn’t the first time she’d heard it suggested that the wrong Dole was running for President. Her husband remarked frequently throughout his uphill campaign, “I’ve even had a lot of people kid me that we should have a Dole-Dole ticket. And I said, ‘But I don’t want to be Vice President.’”

1988 has been the year of the “new political wife”—women like Jeanne Simon, a lawyer and former state legislator, lawyer Hattie Babbitt and author Tipper Gore, who have their own careers and operate as full partners with their husbands. Yet Elizabeth Dole was the only candidate’s spouse—indeed, the only woman in America—who was powerful enough to wake up in the morning and honestly wonder whether she’d finish the year as First Lady, Vice President, or among the unemployed.

“That was a very clever introduction,” Elizabeth Dole said to the man in Sumter, flashing one of her thirty-carat smiles. “How ‘bout just travelin’ along with me and sayin’ that?” The man looked as if her were about to say yes. Yet there’s a curious thing about those smiles. They belie the fact that inside that gracious brunette is a tough, shrewd pol who can really play ball with the big boys.

After assuring the sparse crowd how much she missed her husband on these long solo campaign swings, she began her speech on behalf of Bob Dole with an anecdote designed to reveal more about her.

“One Sunday not too long ago we were back in Washington, back from church, and we were sort of browsing through the newspapers and suddenly he spotted one headline that stated Dole’s position on a particular issue. His brow kind of furrowed and he looked over and me and said, ‘Elizabeth, what in the world is this? This is simply not my position.’ Well, I glanced over the headline and I said, ‘No, Bob, that’s not your position; it’s mine.’” She got a big laugh and was on her way.

After reminding her audience that she was “fluent in Southern,” and making sure they knew she had served in her cabinet position for nearly five years, “longer than anyone else at that job,” she sought to deflect the criticism that she had given up her career for her husband’s. Comparing herself to a man—ex-Labor Secretary William E. Brock, who resigned from the cabinet to manage Bob Dole’s campaign—she pointed out that Brock had taken no heat whatsoever for his decision. Only then did she begin a sincere and impassioned speech for her husband.

When it was over, Harold Lyles, the Republican Chairman of Sumter County, asked the inevitable question: “How ‘bout a Dole-Dole ticket?” “I’m not sure the country’s ready for that.” Elizabeth Dole smiled another of her dazzling smiles. “But there’s gonna be a woman President in our lifetime. I know that,” she said, implying by her answer that when he said “Dole-Dole” he put E before B.

“If there’s gonna be a woman President, it’s gonna be you,” he confirmed.

“Oh thank you, you give me the energy to keep chuggin’ along.”

Thus emboldened, the southern gentleman started laying it on. “I noticed how much prettier you are because you lost some weight.”

“I’m afraid it’s goin’ back up.”

“No, cuz I noticed it is not.”

“Bless you, thank you. That’s a nice compliment.” She gave his arm a little squeeze. “Bless you.”

“You look a lot prettier than you did a year or so ago,” Lyles beamed. By this time many women in her position would have been ready to bop him, but Mrs. Dole was now speaking fluent Southern: “Isn’t that a nice compliment comin’ from a good-lookin’ man!”

Does anyone wonder why this woman has, as Ralph Nader once stated, “always stayed one smile ahead of her critics”? Her aides say that most people who come into contact with Elizabeth Dole are in awe of her. “She is irresistible, certainly one of the most intelligent, articulate and persuasive people I’ve ever seen,” says Jim Murphy, vice president of airspace and airports for the Air Transport Association (ATA), the airlines trade association. “At the same time, she’s a very elusive lady—I bet you’ve got a lot of contradictions on her.”

In fact, contradictions abound. Veteran syndicated columnist Mary McGrory says, “She’s the most baffling person of all the people I’ve seen in this campaign. I just can’t get past the gush.”

Meet the contradictions

On the campaign trail, Elizabeth Dole relies on warmth and sparkle, delivering her messages with sincere intensity. How sincere is she? On the morning of the New Hampshire primary, when a Gallup poll and political pundits said Dole would clobber Bush, Elizabeth Dole gave a speech expressing “my heartfelt thanks” to the people of New Hampshire, telling them how special they were and how sad she was going to feel about not flying into New Hampshire anymore. (The press corps snickered that she had made the exact same speech to the people of Iowa the week before.) Later that day, at a shopping mall, an ex-flight attendant somewhat inarticulately reproached her for being too cozy with Frank Lorenzo, chairman of the board for Texas Air, the company that owns Eastern Airlines and Continental. “Why are you asking me about this?” snapped Dole. “I’m no longer the Secretary of Transportation.” Apparently the people of New Hampshire were less “special” when they chose to be critical. (Although the complaint seemed fair enough—when the two-career couple goes campaigning, both records end up on the line.) “She has a style that makes people believe she’s very humble and warm and caring,” says a former Undersecretary of Transportation. “Then people discover that’s not necessarily true—she’s out for herself.”

There seem to be at least two sides—and maybe more—to the elusive Elizabeth Dole. For example, the right wing of the Republican party distrusts her because she began life as a Democrat and worked hard for liberal “Great Society” programs under Lyndon Johnson. While working on Richard Nixon’s White House Committee on Consumer Interests, she became an Independent. It was only after Elizabeth Hanford, then a federal trade commissioner, married Bob Dole at age thirty-eight that she registered Republican. On the other side of the political coin, many feminists once considered her an ally but have since come to regard her as merely expedient because after becoming Secretary of Transportation she abandoned her support of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Nonetheless, among government agencies she took the lead in day care by establishing a center at the Department of Transportation, and was genuinely moved to tears on the campaign trail when she saw an abused child at a shelter for battered women. But the Center for Auto Safety in Washington D.C. charges—with impressive documentation—that under her stewardship, the Department of Transportation failed to demand changes in or to recall North Carolina-manufactured Thomas Built school buses, even after the department’s own tests and those of the National Transportation Safety Board showed they were defective. In 1985 and 1987, two accidents involving those buses killed eleven children and one adult, and injured thirty-seven others in North Carolina and Florida. Elizabeth Dole—who bills herself as “the safety secretary”—counters that the tests conducted on the buses by the National Transportation Safety Board “were meaningless, since they used a different test than provided in our regulations.” The Center for Auto Safety charges that the buses’ defective floor boards, which separated on collision-impact, increased the number and severity of the injuries suffered by the children. The Thomas Built school buses continue to roll.

Jim Murphy of the ATA rhapsodizes, “I have seen her conduct detailed briefs on major regulatory actions without a note. She did her homework.” But, according to Murphy, Dole nonetheless failed to meet the biggest challenge facing the nation’s airways. “She was too slow rebuilding the air-traffic control system following the PATCO strike in 1981,” he says, explaining that she did not call for more air-traffic controllers until after it became clear Congress would mandate them. “All the energy to get more controllers came from Congress, not the Department of Transportation.”

“She increased the number of air-traffic controllers incrementally throughout her career,” counters Jenna Dorn, one of her closest aids. Implying that Dole fought for the money to get controllers, but was denied support by others in the Administration, Dorn contends that “occasionally she took hits in the press for not getting things she’d actually fought for.” But, says one Dole supporter, “I’ve never seen her lose a battle on which she really chose to fight.”

When an old schoolmate was dying of cancer a few years ago, Elizabeth Dole treated her and her son to a weekend in Washington, fulfilling the woman’s lifelong dream of visiting the capital. The other side of such genuine acts of kindness, say critics, is that when crossed, both Doles can be punitive. “You’ll never know they’re doing it to you—it just gets done,” says a Republican woman who disagreed with Dole at an important meeting and thereafter was dropped from the meeting list. Others agree. Dorn attributes that kind of talk to envy. “It’s hard for some people to accept that this woman appears to have it all—not only is she unselfish, giving, brilliant and pretty, she also has a husband who is famous, able and important. She gets penalized.”

Jealous or not, some high-level Republican women are Dole’s most devoted detractors, portraying her as cunning and callow. (None was winning to go on the record for fear of angering the Doles.) “She’s really an operator,” says one GOP woman who has worked with her closely. “She has no idea at all about what she wants to get done, but she has tremendous zest for the process. She’s only interested in the game of success and advancement.” Some of this criticism stems from Dole’s honeychile style, which is appealing to some, off-putting to others. “Other women [in the Administration] don’t like her,” claims this top-level Republican woman. “It’s the manifestation of the southern business at one point and the feminism at the other point. There’s no intellectual attempt to put them together—they alternate, depending on who’s in the room. It’s just an act, and the women resent that.”

Top labor lawyer and Republican activist Betty Southard Murphy disagrees. “If George Bush wants a woman running mate,” she says, “he would be well advised to look at Elizabeth Dole. It’s not just that everyone knows her name and that she’s a terrific campaigner. She’s also cool, well-controlled, effervescent, and unlike a lot of women, who marry prominent men and get to certain positions, she believes in her own capabilities.” So does her husband. Bob Dole thinks his wife would make a great Vice President for George Bush. “She’s a very distinguished lady; she understands politics, she has great rapport with people. I think she appeals to people pretty much across the political spectrum.”

Just who is this complex woman who may become America’s first woman President or Vice President?

Her roots—and political routes

In the Doles’ joint autobiography, Unlimited Partners, Elizabeth Dole recounts her struggle to overcome an overemphasis on career and ambition with a search for greater spirituality. “The Holy Grail of public service became very nearly all-consuming,” she writes, and says in another passage, “I realized that though I was blessed with a beautiful marriage and a challenging career, my life was close to spiritual starvation.” She recounts that her Methodist faith was renewed in the early 1980’s in “spiritual-growth” meetings—which amounted to weekly group therapy sessions—in a church not far from the White House, where she worked. “During these Monday night meetings I came fact-to-face with a compulsion to do things right and the companion drive to constantly please.”

Admitting these imperfections, including her perfectionism, appear to be the most personal statements she’s ever made publicly. Both traits were manifested early.

Her mother remembers that on the night of her daughter’s junior high graduation in Salisbury, North Carolina (population 22,000), Liddy, the adored daughter of a wealthy flower wholesaler, came into her parents’ bedroom to discuss something. Mindful that her older brother had previously won the Rotary Club citizenship cup, Elizabeth was worried her mother might think less of her if she didn’t win, too. “Now, mother,” she said, “I’m not gonna get any awards tonight, but I want you to know I have tried.” Elizabeth won not only the citizenship cup that night, but also the essay award—two cups. “As I think back on it now,” recalls her mother, “she was preparing me. She didn’t want me to think she had failed.”

As far back as grade school, little Liddy elected herself president of her reading society. She also ran for other offices, including positions girls weren’t supposed to try for. “We sort of pushed her, well, stood behind her in things that developed her speaking ability,” says her mother. “We felt that even girls needed to be able to participate in discussions or meetings.” But a traditional southern woman was what Dole was reared to be. Says Mary Hanford, “I patterned Elizabeth’s life after my own. I wanted her to take home economics, get married and come back and live next door to me. The first thing I had to face up to was political science.”

Liddy ran for student-body president in high school, then not a “girl’s office,” and while she was away serving as a page at a convention of the Daughters of the American Revolution, the boys who opposed her tore down all her posters and banners. “I saw no tears,” says Mrs. Hanford. “Elizabeth said she felt good about it because those boys cared enough about her to tear down those signs. She said losing was a good experience to learn.”

As an undergraduate at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, debutante Liddy continued to shine, not only as a political science major elected to Phi Beta Kappa, but as student-body president of the women’s college and as May Queen. After graduation she went north to earn a masters degree in education and government at Harvard while modeling on the side. She also worked in the Harvard Law Library, trying to decide whether to enroll. Congresswoman Pat Schroeder, then in her first year at Harvard Law, recalls, “I remember saying to her, ‘C’mon, do it,’ but she was reluctant.” Finally she did decide to go. (Dole relates in her autobiography that when she informed her mother she was enrolling in Harvard Law, Mary Hanford smiled through dinner and then went home and vomited.) Dole’s nickname at Harvard was “The May Queen with a brain.” Her class was only 4-percent female, and Schroeder says that in those days, anyone who attended emerged a feminist. “Women felt under siege there—they were treated like something from another planet.”

After graduation, Dole’s first job in Washington was to organize the first national conference on education for the deaf at the liberal Department of Health, Education and Welfare under Lyndon Johnson. By 1968, when Nixon became president, she was a gung ho consumer advocate working on the President’s Committee on Consumer Interests. It was through her boss there, Virginia Knauer, that she met Bob Dole in 1972. “I did notice very definitely that he was an attractive man,” she says. The Senator, whose right arm is paralyzed from a World War II injury, was separated but not yet divorced from his first wife. Although he called Elizabeth a few times, they didn’t date for ten months. His explanation: “I was busy.” Finally, after a three-year courtship, during which they lived in separate but equal apartments in the Watergate, they married in 1975, and gave birth sometime later to the concept of the Power Couple.

Robin Dole, the Senator’s daughter from his previous marriage, remembers giving her new stepmother flowers on the first Mother’s Day after the wedding. “Elizabeth cried. She had never thought of getting something on Mother’s Day, so she was really touched.”

After the wedding Elizabeth moved into Bob’s small bachelor apartment. Such is the nature of their frenetic, outer-directed lives that the millionaire Doles still live there, cramming their exercise bicycle into the den. Neither cooks, and they can’t remember the last movie they saw. They meet Robin for occasional Sunday brunches, and although they’re extremely well-connected with the powerful of both sexes, Elizabeth says her closest friend is her mother. (She had a second telephone installed in Mary Hanford’s home so she could always be sure of reaching her.) Not surprisingly, neither Dole is big on vacations. In fact, since their marriage twelve years ago, one or both has nearly always been up for a job or campaigning for something. And what of the cardinal rule of politics, that there be only one star in the family? “There’s no competition at all between us, and no overshadowing,” says Elizabeth Dole. “I think it’s a very healthy partnership.” (It appears, however, that the Senator has seniority. Top Republican strategist John Sears remarks, “The only ways Elizabeth Dole could be President would be over Bob Dole’s dead body.”)

In 1976, about a year after her wedding, Elizabeth took a leave of absence from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and campaigned with her husband, who was in the presidential sweepstakes even then as Gerald Ford’s running mate. The GOP narrowly lost to Jimmy Carter, but Elizabeth had garnered her first campaign headlines.

In 1979, she resigned from the FTC—where co-workers say she was a staunch advocate for women, minorities and the poor—to campaign full-time for Bob Dole in his first bid for the Presidency. When he dropped out early, she worked fervently for Ronald Reagan and eventually landed in the Reagan White House, as assistant to the President for Public liaison. There, the former champion of the consumer movement and supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment became a strong advocate of business and was, as one lobbyist put it, “gagged,” never permitted to speak out publicly on women’s issues. After she left the White House, however, she continued to lobby the President’s staff to accept pension reforms beneficial to women and to strengthen the child-support payment laws.

Ironically, it was women’s pressure on the Reagan White House that brought about the biggest promotion so far in Elizabeth Dole’s career. When Reagan was elected in 1980 and commenced his “revolution” of cutting taxes and social programs while increasing the military budget, unemployment shot up and women began expressing strong disapproval in the polls. This “gender gap”—meaning that men approved of the Reagan program more that women did—became more concrete in the 1982 Congressional and gubernatorial elections, when Republicans lost key races because of women’s votes against them. Eager to demonstrate that there were impressive women on the Reagan team—when, in reality, they were few and far between—the Administration then gave increased visibility to Elizabeth Dole, who previously had often been shut out of White House decision-making because of a suspicion that she was a back channel to her powerful husband. A few months after the ’82 elections, she landed her cabinet position.

Debits and credits

Some of Dole’s accomplishments as Secretary of Transportation are well-known. She fought hard to raise the drinking age to twenty-one across the country so that traffic fatalities would be curtailed. Norma Jean Phillips, national president of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, says, “Elizabeth Dole stood on the steps of the Capitol with us to join in our fight.” Phillips estimates that, as a result, 1,200 teenage lives will be saved each year. Dole also succeeded in mandating high-mounted brake lights on all new cars. She managed to lease the Washington National and Dulles airports from the federal government to a public authority, something that was first proposed in 1949, but had not been accomplished by any previous Secretary of Transportation. She also got Conrail, the giant federal railway system, sold to private hands. Nevertheless, her critics are numerous. Those inside the agency cite her perfectionism and preoccupation with petty details, as well as her tireless pursuit of publicity—whenever the news was good. “Anything bad was up to her subordinates to announce, without exception,” says a veteran aviation official.

Outside critics go further. “All that mess out there in the air is hers,” charges respected aviation journalist Joan Feldman. “She couldn’t have waved a magic wand and made it all right, but she could have made a start, and she did not. She appeared at a critical time in the history of the aviation business, and she fell down on the job.” Experts rate her political skills as outstanding, her managerial skills mediocre. “She stayed too long at the fair,” says a former Undersecretary of Transportation. “She got caught up believing her own rhetoric and didn’t really deal with the core issues.” One of her severest critics is Ralph Nader. “She came in like a consumer advocate and came out like a corporate advocate. She ran the Department of Transportation like General Motors would have,” he says. “She learned how to be a ceremonial leader from Reagan.”

But so what? Will any of Dole’s debits or credits show up on the nation’s TV screens between now and November, or beyond? Probably not. Today’s formula for national political success is name recognition plus star quality—which makes many people think that Elizabeth Dole can go all the way. After all, the camera loves her, and she’s a proven vote-getter. When Bob Dole, having recently won his party’s Iowa caucuses, was asked in New Hampshire how many votes he owed to his wife, he quipped, “About half.” “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says prominent conservative columnist Robert Novak. “People voting for a man because of his wife.” Evidence of this was everywhere during Bob Dole’s campaign. “I’m sick of women being downgraded and denigrated,” said Nan Dubrowski, a New Hampshire Republican who voted for the senator because of Elizabeth. “Hart’s wife turned me off totally. Bush’s wife is invisible. I feel it’s time for a woman to come on who isn’t overbearing but has a head on her shoulders and says what she wants to say.”

If Elizabeth Dole becomes a candidate, will parts of her record in the Department of Transportation be used against her? Political operatives pooh-pooh the notion that the public cares how anyone performs as Secretary of Transportation, unless he or she is truly awful. “After a few years, we don’t remember who the Secretary of Transportation was,” says John Sears, who has managed presidential campaigns for Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. “She didn’t do any harm.” “All cabinet secretaries get criticized, without exception,” says Betty Southard Murphy dismissively.

Can Elizabeth Dole make the enormous leap to the Presidency? Her foundation is sound. “Part of the trick is getting publicity—and she’s gotten some,” says Sears. “Part of the proof of qualifications is that you’ve been handing around the right places long enough—she’s done that. But she’s never held elective office, and that’s a drawback. You’d have to figure out a path for her to be President.” “She can do anything she wants,” states Bill Brock, who was Bob Dole’s campaign manager. Would she be a viable vice-presidential candidate, for Bush or anyone else? “Absolutely not,” says Brock. “She’s be a viable presidential candidate.”

Pat Schroeder, who dipped her toe into presidential waters then stepped back, says her gut instinct is that the cautious Dole, who had to be talked into Harvard Law School, will never go for it. “You’re out there in front of the whole world twenty-four hours a day on their terms. She knows how it feels. She’s wealthy enough and has enough power that she doesn’t want to risk that.”

Dole herself offers mixed messages about her possible candidacy. Though out on the stump she seemed comfortable with the idea of being a presidential possibility, in formal interviews she’s more cautious. “I’m not focused on running for national office,” she said during her husband’s New Hampshire campaign. “I don’t have plans to run myself.” She does say, however, that “people on the campaign trail seem to be very much attuned to having a woman be President of the United States. Certainly Margaret Thatcher has been a great example. I think a lot of people relate to her.”

If George Bush does choose Elizabeth Dole as his running mate, we’ll find out how much she relates to Thatcher. If a southern Christian woman is not needed to activate interest in Bush’s candidacy, Elizabeth Dole can always get an Administration job if the Republicans win, or take seats on a dozen Fortune 500 boards if they don’t. She can also go home to North Carolina and challenge the formidable conservative Jesse Helms for his Senate seat. Her mother doesn’t think she’ll run for anything.

“These articles that make her appear grasping, they’re not right. She has no great run for the Senate—she has never run for anything. She always says God has opened the doors for her.” Maybe so, but throughout her life, once that door is divinely cracked, Elizabeth Dole has always kicked it wide open.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.