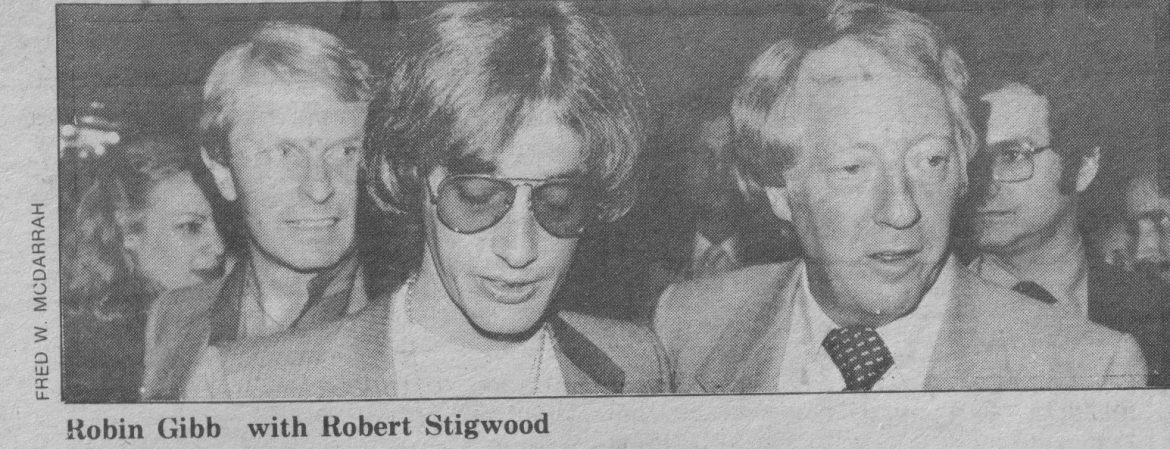

Original Publication – The Village Voice, October 8, 1980

The Bee Gees, the high-pitched heart, soul and bank of the Robert Stigwood entertainment empire and one of the largest selling acts in the history of the music business, have fired Stigwood as their manager and are suing him for $75 million.

In a suit filed Monday in New York State Supreme Court, the Bee Gees charge Stigwood with fraud, conflict of interest, and unfair enrichment at their expense. In addition, the suit claims that a preliminary audit of Bee Gees record sales by independent accountants hired by the group and completed last September has found more than $16 million in unpaid recording royalties owed them. Stigwood, in return last week, asked a London court to declare his contracts with the Bee Gees remain in full force.

The Bee Gees, Australian brothers Maurice, Robin, and Barry Gibb, were one of the driving forces behind the multi-billion dollar disco industry. Album sales on their original soundtrack recording of Saturday Night Fever were 30 million and their soundtrack album of Grease helped make that film one of the highest grossing in Hollywood history. Manager of the group since 1968, the flamboyant Stigwood, known for his lavish parties, luxurious yacht, and endless stream of young admirers, is widely credited with bringing the Bee Gees to their current success. He and his companies – the Stigwood Group – which are partly owned by the European conglomerate Polydor International – control virtually every phase of the Bee Gees’ careers, from music publishing to merchandising their names on products.

Now the Bee Gees want out. They have retained lawyer John Eastman, who successfully sued to terminate the Beatles’ relationship with manager Alan Klein. In addition to the $75 million in damages they say Stigwood owes them they are also asking $75 million from the Polygram Group and $50 million in punitive damages.

If Stigwood were only the Bee Gees’ manager, for which he receives 25 per cent of all three Gibb brothers’ gross income, he would be a millionaire many times over. But, according to the suit, Stigwood betrayed the trust the Gibbs placed in him and treated the group as if it was his own private Fort Knox.

The suit charges that Stigwood never tried to peddle the Bee Gees to any record company other than his own; and that the recording and publishing contracts he made for them – in effect with himself – were “grossly inadequate.” The suit alleges other fraudulent acts as well: that Stigwood pocketed large amounts of money which were advanced for performing rights from BMI (Broadcast Music Inc.); that he registered Bee Gees song copyrights and master recordings in his own name instead of the Gibbs’ in express violating of their 1977 contract; and that by creating multiple periodic accountings among his various companies, he delayed paying millions of dollars of royalties to the Bee Gees for two years or more. In addition to those charges, the suit claims that Stigwood’s companies tried to hinder accountants hired by the Gibbs and refused to cooperate with them.

Many of these charges are fairly standard in music business disputes, though the extent and the vast money at stake here is unusual – particularly because Stigwood has portrayed himself as a man in awe of the artists he represents, a shy man who worships their talent and will go to any lengths to keep them happy.

The Bee Gees’ lawyers are claiming something else quite out of the ordinary. The suit alleges that “for at least 10 years a major part of the success and income of defendant Robert Stigwood have been related directly to the creative activites of the Gibbs.” It states that when Stigwood sold a part of his empire to Polydor International, he gained vast profits on the basis of the Bee Gees’ contracts with him. But though the Bee Gees were his “live equity,” he did not share a penny of the profits with the group.

In London Tuesday, Robert Stigwood told the Voice: “These ridiculous allegations are false and without foundation. This is only an ill-advised stunt. I want no part of it. I have instructed counsel to see the truth is told and those responsible for this travesty are made to account for their misconduct. The legal process has enough to do without being bogged down in this kind of self-serving nonsense.”

The Bee Gees evidently became suspicious of Stigwood sometime last year when one of their lawyers ordered a routing audit which discovered millions of dollars in unpaid royalties. The lawyers did not plan to file the suit until later this month. But the gun was jumped when a furious Maurice Gibb, upon hearing the full extent of the charges last week, drove from his country house outside London and stormed into Stigwood’s London office to confront him. Stigwood countered by hastily filing his one-page writs.

Relations have been especially cool between Stigwood and the world’s richest male sopranos for the last several months. When filmmaker George Lucas approached the Bee Gees with a film idea not long ago he was reportedly informed that legal action would be taken if the deal was not arranged through the Stigwood Group. Barry Gibb, the only one of the three brothers who does not have a contract with Stigwood for his individual recording projects, recently produced Barbra Streisand’s LP, Guilty, number 15 this week on Billboard’s Hot 100. He also sings duets with Streisand on two of the cuts. According to a spokesman at CBS, when Gibb undertook the assignment he represented himself as a free agent. But Stigwood’s label RSO heard of the deal and threatened an injunction to stop the release of the record. The spokesman says an amicable agreement was finally reached.

The last recording contract negotiated between Stigwood and the Bee Gees in August of 1975 was set to run for five years or eight albums, whichever was longer. To date the Bee Gees have produced six LPs and what will happen next is anybody’s guess. With this many millions at stake it’s hard enough just stayin’ alive.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.