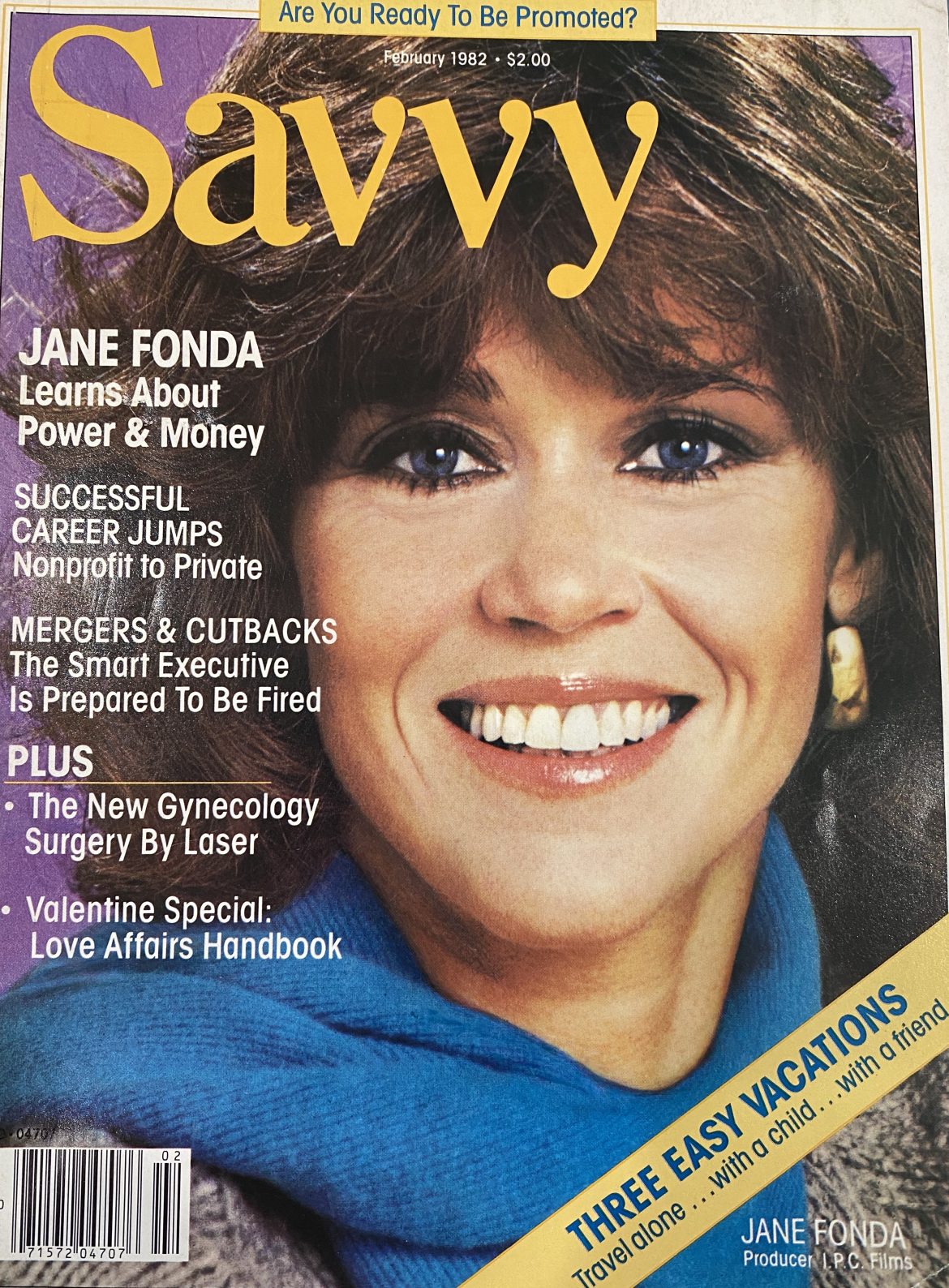

Original Publication – Savvy, February 1982

Today, as entrepreneur and producer, Fonda manages the money that makes the movies that carry the messages that she believes in. Says the 44-year-old star, “It’s time to make my contribution.”

Jane Fonda pursues five separate careers at once. You have just met, thanks to an intensive television blitz, the fitness freak – wealthy entrepreneur of three successful exercise centers – and you already know the political activist. Now say hello to the ideologue producer and devoted family woman – political wife, guilty mother, eager-to-please daughter – and have you met the soft-hearted boss?

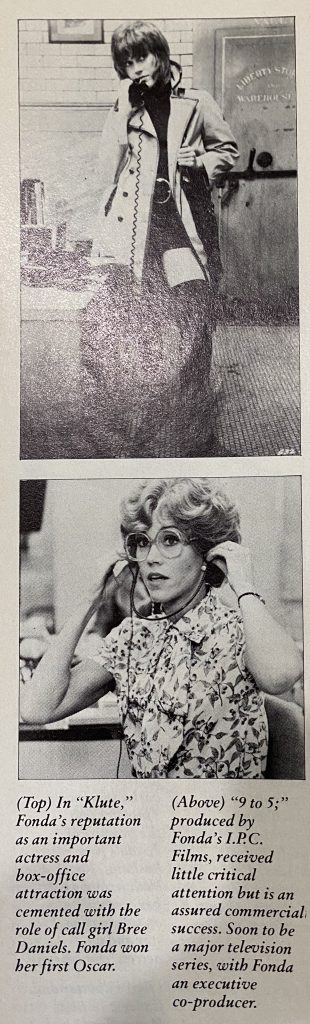

Complicated casting for a messed-up rich kid who vomited her way through Vassar trying to stay thin, became Barbarella, that space-age Barbie doll, in France and went on to be vilified for her radical politics as “Hanoi Jane” less than a decade ago. Today, at 44, in an amazing comeback from those difficult days when she wasn’t sure she’d ever work in Hollywood again, Jane Fonda is a two-time Academy Award winner who is simultaneously educating herself in business and demonstrating the kind of power and control that only the most seasoned C.E.O.’s exhibit. “Over the past year I’ve begun to see that it’s time I made myself felt – time to make my contribution,” Fonda says.

To say she is driven is the height of understatement. Fonda is a compulsive overachiever and she wants her views – whether on fitness, banking, nuclear energy – to receive as wide an audience as possible. So Fonda, the embodiment of the Protestant work ethic, has constructed a life that enables her to make a great deal of money without sacrificing her principles, using the system she criticizes to finance and deliver her messages. It’s quite a juggle and no mean achievement.

Jane Fonda needs tangible evidence that she is accomplishing something. In whatever she takes on, she tends to go to the extreme. She likes to sweat. When she’s exercising, she wants to feel the muscles “burn,” to feel the pain that is the proof.

At 5:30 A.M. she runs six miles on the dewy oceanfront palisades near her modest Santa Monica home. By 7:05 she is in Beverly Hills, clad in a brightly striped leotard and happily soaking wet once again, teaching an advanced class at one of her three fitness centers – Jane Fonda’s Workout. People arrive for eight o’clock classes and press their faces against the steamy window of the studio for a glimpse of her; it is impossible to forget that she is a movie star.

Workout is aptly named, for throughout the day and far into the night, that is what Jane Fonda does: work at, work on, work out. Her motto is an adage of Martha Graham’s: Discipline is liberation. Discipline breeds energy, energy fuels the drive.

“Come on now,” she pants to the class of 35, “Let’s pull weeds.” Her arms fly from one leg to another in fierce movements. “This is positive pain,” she exhorts, “Like childbirth.”

A psychohistorian could have a field day analyzing what drives Jane Fonda after reading her father’s biography, My Life, as told to Howard Teichmann. Jane’s childhood seems to be either a blueprint for disaster or furious self-control. Henry Fonda has had five wives – Jane’s mother, Frances, was his second – and off screen the beloved film idol was a frugal man given to moody silences and sudden rages.

Frances De Villers Seymour, first married to George Tuttle Brokaw (his former wife was Clare Booth Luce), was an aloof woman who placed a great importance on being rich and thin.

“She was a conservative Republican,” Jane recalls, “Very society oriented, and she had a safe in the middle of the bedroom where she kept her jewels. The trappings of wealth are familiar to me. Money, power, wealth are all familiar.”

When Jane was born she was whisked off to the nursery with a nanny, and her father was not allowed to touch her. “I had everything, but I needed permission to see my own baby,” Henry Fonda says in the book. “It makes me sad that Jane grew up without being hugged or fondled,” But while “Lady Jane,” as she was nicknamed, was growing up in Bel Air and Connecticut, she did not want her mother to touch her, convinced that her mother wanted only sons. “I didn’t like her near me,” Jane relates in her father’s book. “I didn’t like her to touch me because I knew she really didn’t love me.”

Frances Fonda maintained an office with a staff of six and conducted business from her Bel Air bedroom. She handled all of her husband’s business affairs (not terribly well, according to biographer Teichmann) and also did his tax returns. Plagued by severe depression, Frances committed suicide when Jane was 13, slitting her throat from ear to ear. It was several months later that Jane learned how her mother had died, by reading about it in a movie magazine.

Both Jane’s parents were perfectionists. Her father withdrew into his work, while her mother was precise and exacting. “My mother was an excessively organized person,” Jane says. “I have to fight against that tendancy.” In any case, her mother’s example of working in the bedroom was one that Jane has totally rejected. “That was a role model I never wanted to emulate.” Yet when asked how she researched the behavior of the chairwoman of the board she plays in her latest film, “Rollover,” Fonda answers quickly, “I just remember my mother. I remembered her dressing room with mirrors all around and wanted them in the movie.”

Lee Winter, Jane Fonda’s character in “Rollover,” is a former movie star married to the head of a a large corporation. When he dies mysteriously, she takes over his job. “I felt that Lee could be comfortable doing this if she had been an actress,” Fonda says. “Women who have become powerful in Hollywood, like Katharine Hepburn, Joan Crawford or Doris Day, who negotiated their own deals, were comfortable with power. Katharine Hepburn told me she always wore her highest heels when she went to see Louis B. Mayer so she could tower over him when she wanted something from him.”

Like these women, Jane Fonda has, in her own way, been able to get what she wants from the Hollywood system.

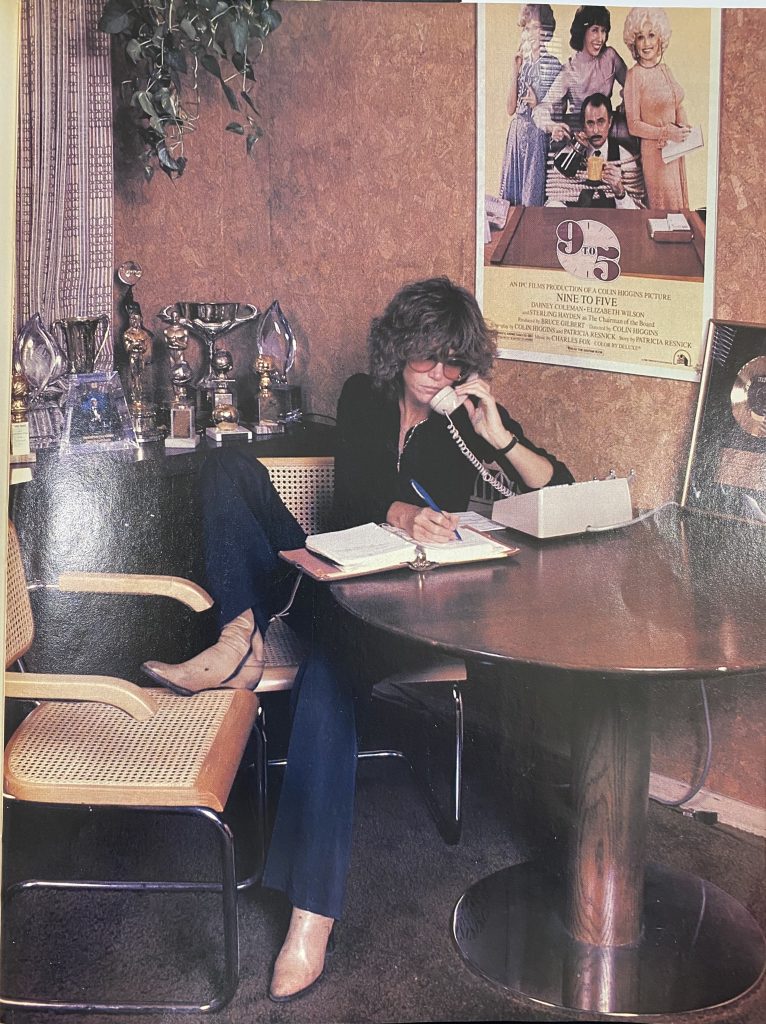

Fonda is more than just one of Hollywood’s highest-paid actresses, earning $2 million per picture plus a percentage of gross profits. She and her partner, 34-year-old Bruce Gilbert, have produced three successful movies in a row, in a town where your track record is the key to getting exactly what you want.

Starting with “Coming Home” in 1978, their I.P.C. Films company (I.P.C. stands for Indochina Peace Campaign, where they first met) has produced three this and no misses, each film earning more than the last. They have also co-produced “On Golden Pond” and “Rollover.”

“Coming Home” cost $5.2 million and made a profit of $26 million. In 1979 “The China Syndrome,” the $6 million thriller about the dangers of nuclear energy, earned over $40 million. But I.P.C.’s real blockbuster so far has been the least critically acclaimed – “Nine to Five,” the screwball comedy about the travails of female office workers, starring Fonda, Dolly Parton and Lily Tomlin. To date, “Nine to Five,” which has grossed over $100-million worldwide at the box office and has returned a whopping $55 million in film rental fees to its distributors, Twentieth Century Fox, even before projected multimillion dollar sales to network and cable television. It is probably the most profitable “woman’s picture” ever made.

Jane Fonda has profit participation on that $55 million and any further profits as both producer and actress. It has been reported that so far she’s earned $7 million on “Nine to Five.” I.P.C. also owns 50% of the television rights for the new “Nine to Five” television series, which will debut in early spring on ABC. Gilbert and Fonda are the executive producers. These days a top television series with a five-to-ten-year run in syndication, such as “All in the Family,” “M*A*S*H” or “Happy Days,” can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

On the exercise circuit, Jane Fonda in a leotard is as great a draw as she is at the box office. Thirty-two hundred people a week come to Jane Fonda’s Workout in Beverly Hills; all pay $7 a class for any one of 160 classes, which run six days a week. At Workout, thought, each inch shed or muscle toned is for a cause.

All profits from Workout go to the Campaign for Economic Democracy (C. E. D.), a grass-roots political organization with thirty chapters throughout California. These days C. E. D. is concerned with environmental cancer, abortion rights, tenants’ rights, a direct-mail program that Fonda says her exercise book will pay for, and the political aims of her activist-writer husband, Tom Hayden, who is likely to run for California State Assembly in 1982. In 1980 Workout came to the San Fernando Valley, and in 1981 Fonda opened a third Workout in San Francisco.

Much of the success of the three centers is due to the cachet of Fonda’s name, but Jane herself also imparts great enthusiasm to the other instructors and students, and often substitute teaches when she’s not making a film. In the booming fitness business, where a successful center can easily clear $500,000 to $600,000 in yearly profits, and where demand outstrips supply, Jane Fonda’s Workout concept, largely culled from others but personally designed is considered tough and invigorating. And, not to let an opportunity slip by, Fonda has recently published Jane Fonda’s Workout Book and is also peddling a Jane Fonda Workout tape and record.

Is this Jane Fonda the capitalist?

“I am not by nature a businesswoman,” Fonda said recently in her office, which is housed in a far-from-glamorous cluster of funky pre-fab building on the Twentieth Century Fox lot. “Over the last ten years I’ve given most of what I’ve earned to political issues and candidates. I’ve had no investments and have never been able to save. Now that my career is on the upswing, I’ve decided to manage my own money.”

As might be expected, though, when E. F. Hutton talks, Jane Fonda does not necessarily listen. One of the first items she handed her financial advisors was a list of proscribed investments: No investing in oil companies, petrochemicals or pharmaceuticals. No speculation in foreign currency, and no ownership of real estate unless tenants’ rights are strictly honored and there is no environmental objection.

“I am 44, and getting this money is brand new,” Fonda says. “I know it won’t last forever. I want to be true to my beliefs, to invest in issues that make sense socially. The same is true for the films I do.” As for future investments, Jane does not reveal anything beyond saying that she is looking at cable television and alternate forms of energy, including solar and windmills.

In the course of a day, Fonda gets a great deal done. Although she considers herself a “big delegator” as well as a self-educator, to her, time isn’t money – it’s the enemy. Consider a typical day:

After teaching her exercise class, Fonda changed into brown jeans, strapless halter, cotton kimono jacket and high backless pumps and went off to a long meeting at C. E. D. On her way home from the meeting, Fonda the mother bought her eight-year-old son, Troy Hayden, a stamp collection book, took a lamp to be replaced, picked up a vacuum cleaner that had been repaired. She also stopped by to visit her bedridden father (Henry Fonda, now 76, has suffered several heart attacks). “I rubbed his feet a little bit,” says Jane the daughter. Once home, it was time to tidy up the house because, in deference to her husband’s wishes, she doesn’t have full-time help.

Before noon, Jane Fonda the executive was in her own nine-to-five office, decorated in leatherette and serapes, making phone calls. Later, in the Fox commissary, Fonda the self-educator lunched with Burt Metcalfe, producer of M*A*S*H.

“He communicated to me the process of creating a television series,” Fonda relates stiltedly, sounding rather ingenuous. “He explained how a script gets created, how many people are present at meetings, the role of the producer, the importance of the writing team and when the producer has to be totally present.”

Back in her office she interviewed a woman for an executive position at Workout. She says both she and Bruce Gilbert prefer hiring women because they make Jane feel more comfortable. “For women who are executives or managers, it’s important to become conscious about the things we have to offer that are different,” Fonda explains. “I think women are more humanitarian and, generally speaking, the profit maxim is not absolutely the only criterion in their decisions.”

Right now, Fonda is grappling with the skills it takes to be a boss. “How do you interview a manager?” she asks, after the woman has left. “I have to get so much better at reading people. How do you elict the kinds of responses that go beyond references and résumés? That’s a skill I have to learn. When you’re trying to juggle a lot, you’re always thinking, ‘What do I have to put off here?’ You have to be constantly sensitive to what you’re putting off, like talking to employees, or else things erupt. I wish I had a better grasp on figuring out what people really want. For example, why is morale declining in the office, and how can I curtail my tendency to just give them all raises, and understand what’s fair?”

Fonda was on much firmer ground discussing publicity with her PR woman for the opening of the San Francisco Workout. Next she made calls about putting a benefit concert together, possibly for television, for the Santa Barbara C. E. D. summer camp fund. By late afternoon Fonda still had several hours of office work left.

It would not be until 7:30 pm that she would leave the office, load up the car, and drive an hour and half to Santa Barbara to meet her husband and catch part of a Jackson Browne concert – a concert for a cause. (Brown is a leading entertainment figure in the fight against nuclear energy.) Only then, around midnight maybe, would she go to bed, at the C. E. D. camp. But at nine the next morning Fonda was scheduled to teach a children’s theater arts class which included her 13-year-old daughter, Vanessa Vadim, by her first husband, French film designer Roger Vadim. Before class, though, she would either run or work out.

Vanessa, her mother explains has just made her first film with a friend – an antismoking documentary. “Watching her,” says Jane, “I felt the way my father must have, watching me. She has potential – there’s obvious talent – but she told me that if she became an actress she wouldn’t have children.” This remark causes Fonda obvious pain.

“It’s very difficult to be as good a mother as I would like to be,” Fonda says. “But I’m lucky. My kids are quite stable and happy, and I credit a lot of that to their fathers. I do feel guilty. But I also know that if I didn’t do what I do, I wouldn’t be a very good mother.”

Jane Fonda’s politics – publicly, at least – have mellowed in recent years. She seems to have learned that a successful activist defines the political parameters, while a politician works within them. Both she and Tom Hayden are active Democrats, staunch supporters of California governor Jerry Brown, and Hayden aspired to high public office as a liberal Democrat. Politics is at the core of her being and is what drives Jane Fonda’s work, including her movies.

All the films she produces follow her interests and are told from a political point of view. “Coming Home,” I. P. C.’s first production, was about the wife of a returning Vietnam Vet. Fonda was deeply involved in ending the war when she and Bruce Gilbert founded I. P. C. Films in 1973, and it took them five years to get the movie made. “The China Syndrome” dealt with nuclear energy, one of the principal issues C. E. D. researches, and still a hot political issue in California. “Nine to Five” was widely criticized for being cartoonlike in its reliance on feminist sloganeering to unravel its plot about women in the workplace, but it was undeniable popular with audiences and put Fonda into contact with thousands of militant office workers all over the country.

Even the least political of the films she’s produced, “On Golden Pond,” which was first a play and which Fonda says she made as a gift to her father, is not without a message. It champions the possibility of a rich and loving life for old people. “Rollover,” a doomsday thriller, which has opened to less-than-enthusiastic reviews, was originally suggested by Tom Hayden and is about what Fonda feels is the excessive secrecy and weakness of American banks that hold billions of dollars of Arab oil money. Next Fonda is said to be looking for a story that will make a good film for contemporary adolescents, possibly because her daughter, Vanessa, is now at that age.

The idea behind their movies, however, says Bruce Gilbert, is to entertain not to preach. “If were making commercial films, we have to have something to say to people, to connect with them. We’re not making documentaries or political tracts. We’re making entertainment with a point of view.”

In Fonda’s pictures the point of view is rarely sacrificed for anything else, no matter how much we might or might not agree with it, no matter how sexy a leading man she has, nor how glossy the packaging. Contrary to the way many Hollywood producers work, Fonda and Gilbert don’t wait for material to come to them – they develop their own subjects. The process requires meticulous research that may take as long as three years. By the time they hire the final scriptwriter, the story line and major characters are all worked out.

I. P. C. has also begun an experiment to help finance the research of magazine writers in order to buy the film rights to their articles on subjects that interest Fonda and Gilbert. Whether I. P. C. can retain a financial interest without influencing the slant of a writer tempted by a movie deal is a delicate question.

What seems clear, though, is that Fonda and Gilbert have been very successful in getting the public to buy their slant. (“Rollover,” may be the first exception.)

When she decided to save money for herself and her family, Fonda wanted to make sure she could provide ongoing funding for her own and Tom Hayden’s political pursuits. Although he has not yet held elective office in California (he ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate in 1976), Hayden is an ambitious, full-time politician. While he provides the intellectual umbrella under which his wife promotes their causes, she is the family’s principal breadwinner. These days campaigns don’t come cheap; in California they can easily cost several hundred thousand dollars. Any business Jane Fonda started would have to earn substantial money – the sooner the better. Cashing in on the fitness fad as a separate way to finance C. E. D. was a brilliant solution.

To run her first Workout, Fonda eschewed those with experience in the field and chose instead a woman whose commitment to C. E. D. was total. From an ad in the C. E. D. paper, Jane hired Mary Kushner, a U.C.L.A. M.B.A. and ex-Sears Roebuck department manager who was not only a C.E.D. member but who had also worked on Hayden’s Senate campaign. “Mary didn’t have a lot of experience,” says Fonda, “But she had devotion and motivation and loyalty. I can trust her absolutely.”

Going against the conventional wisdom of the exercise business, Workout decided not to sell memberships but, like a dance studio, to accept payment per class. “People said we’d never make it ,” states Mary Kusher, but Fonda’s decision to enter the fitness business ignited a small star war among the fit.

Much of Workout was patterned after the successful exercise studios franchised by Gilda Marx, who opened her first studio, Body Design by Gilda, in the San Fernando valley sixteen years ago. Marx, who also owns Flexatard Inc., one of the largest exercise apparel lines in the country, has been a pioneer in melding aerobic exercise set to music and claims she introduced Fonda to it. Marx is ambivalent about Workout’s success.

“I respect Jane Fonda as a unique person, but as one woman to another, I don’t exactly respect her business ethics,” Marx says. Although she credits Fonda’s chaperoning of fitness in the media as having “done wonders” for her Flextard business, Marx charges that Fonda “tried to take one of my best teachers away, and Workout sent some very innocent-looking people over here under-cover, trying to find out where I bought my mats and barres.” Richard Simmons (syndicated T.V. fitness guru), was rumored to be so furious when Fonda took one of his teachers, that he wanted to go on television and tell the world. Apparently today, Simmons feels there’s enough flab to go around for everybody.

Within a year of its opening in May 1979, Jane Fonda’s name did wonders for her own business as well, and the first Workout recouped its initial investment of $200,000. That first year it was enough in the black, even after paying C.E.D.’s expenses, to go ahead with plans to open a second branch. Fonda’s ability to generate publicity was matched by her ability to keep quality teachers loyal to her. After Workout expanded to the San Fernando valley, however, Fonda suffered a temporary setback when she decided to open a Workout in New York.

As problems arose over different New York sites, she withdrew from the East to open her next Workout in San Francisco. For the time being, Fonda has no plans to expand Workout, nor are there plans for a line of Jane Fonda Workout clothes or Jane Fonda vitamins or algae face masks.

“People call us at least once a day to franchise or invest money in us, “ says Mary Kushner. “ ‘Just give us Jane’s name,’ they say. But we’re very protective of what we have.”

Jane Fonda is very protective of what she has, too, especially concerning her relationship with her husband, who has often been accused of freeloading off her fame. For example, a recent item in the powerful Herb Caen’s column in The San Francisco Chronicle about the opening of the San Francisco Workout, ended with the question, “What does she see in Tom Hayden? Gaaaaah!”

“Our relationship gets attacked so often in publications, both right and left. I sometimes think there’s a deliberate conspiracy to break us up,” Fonda says. “They say he’s a conniving man with a secret agenda, that he’s using me, that I’m totally cowed by him and when I wake up some day I’ll finally realize it and get rid of him. It is so very, very, destructive to always hear or read that we’re about to break up.”

In fact, Jane claims, the opposite is true. The intricate balancing act she performs with her energy and time and all the positive attributes of responsibility and accountability she wants her life to reflect could not even occur, she emphasizes, if she didn’t feel secure as a wife and mother. “I feel much more liberated professionally because I’m married, have children, a home, a nesting place.”

Now that her two latest films have opened, her book has been published, and her husband’s political intentions are clear, Jane Fonda is concentrating on producing the “Nine to Five” television series.

“Taking on a lot is nothing new,” says Fonda. “I’ve always juggled a lot of balls at one time. But what age and maturity have brought is that I care more now. I want to be more accountable. I feel a tremendous responsibility in doing T.V. I feel scared about it, but unless we really try it we won’t know whether television is really rotten or not.”

Like all of us, Jane Fonda has moments of fear and insecurity. In casual speech she will refer more than once to “the knot in my stomach,” as she remembers things in the past or contemplates the burdens of her future. One minute she’ll say, “Sometimes I think I’m the luckiest person in the world. There’s nothing better than having work you really care about.” Then a little while later, reaching out to the table next to her and knocking wood about her achievements she’ll laugh and say, “Sometimes I think my greatest problem is lack of confidence.” Of the responsibilities in her life now, Fonda declares, “I’m scared and I think that’s healthy.”

Then slumping back in her chair, Jane Fonda makes a remark that is guileless as it is surprising. “Having this money alters your consciousness,” she says earnestly. “It makes you more understanding of people’s problems and more compassionate.”

Dealing with wealth might be the biggest creative challenge Jane Fonda has ever faced.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.