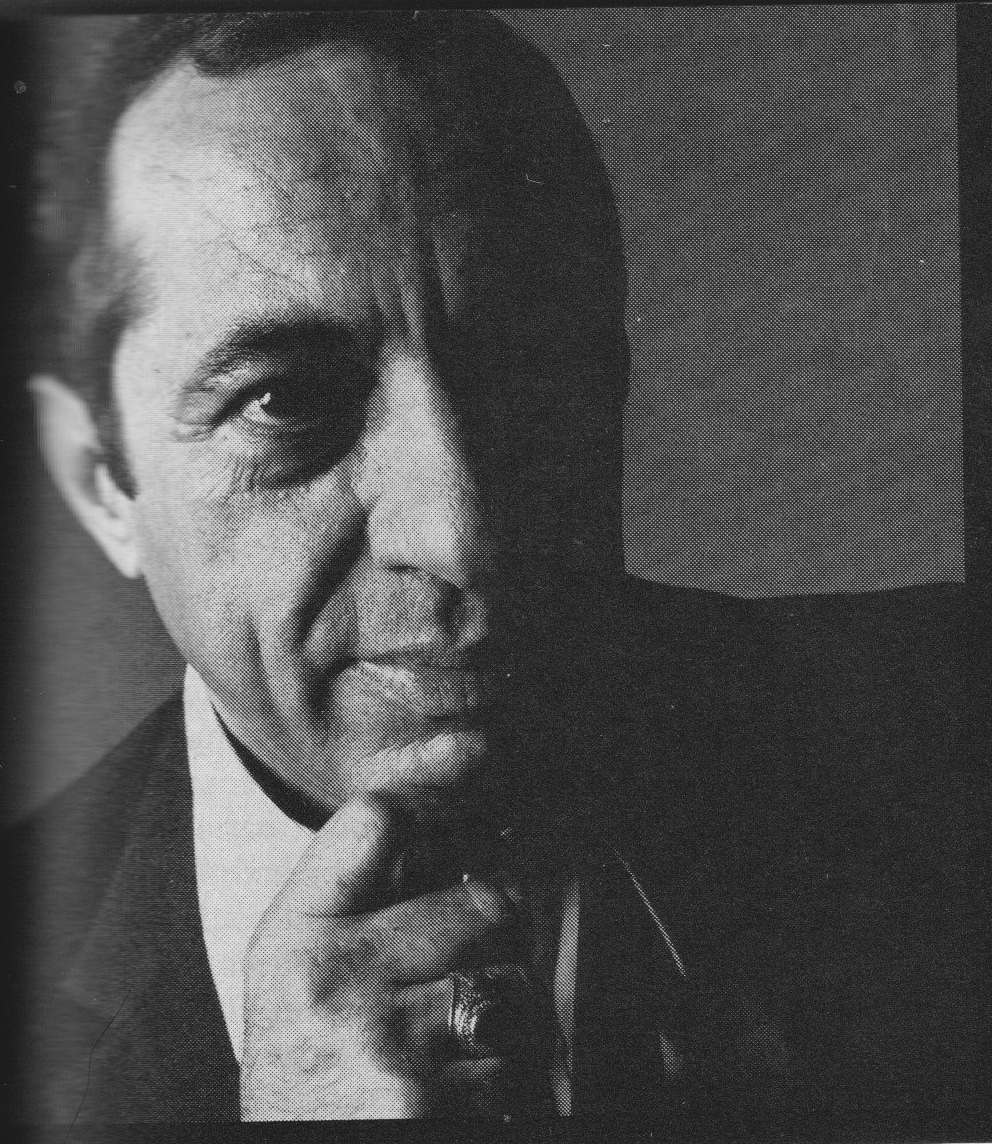

Original Publication: Vogue, January 1985

Mario Cuomo’s vision of government as family, his warmth and humor, and his unique ability to understand both the needs and abilities of women have made the Governor of New York the symbol of a new American morality.

When politics seem silly, or it’s a dull day for a probing mind, Govenor Mario M Cuomo of New York invents alter egos: “Glendy LaDuke” is his nom de baseball, a throwback to his days as a minor leaguer when he wanted to play in two leagues at once. “A.J. Parkinson” is the alter ego responsible for coining aphorisms. “The price for free speech is never too high,” attributed to Parkinson, is on a plaque the Governor presented to the Albany press corps. It took over a year for the reporters who cover him daily to figure out that the thought processes of A.J. Parkinson were remarkably like those of Mario Cuomo.

Despite the wit, his book, The Diaries of Mario M. Cuomo, portrays a soulful man who pits his daily behavior against rigid moral standards and who enjoys intellectual and political battle. Cuomo’s spiritual nourishment comes from his religion, his family – his wife Matilda, three daughters, and two sons – and the French Jesuit philosopher Teilhard de Chardin, whom he quotes constantly. Cuomo, a lawyer and law school professor, has read widely and thought deeply. The proud son of Italian immigrants who owned a mom-and-pop grocery store in Queens, New York, Cuomo, fifty-two, is in fact a restless workaholic who seems fueled in equal measure by tradition, compassion, and ambition.

There’s no question he likes to have the competitive edge. I once made the mistake of asking the Governor how he came to have such enlightened views on women since he grew up as a traditional Italian male. First he laughed. Then he upbraided me mercilessly for stereotyping: For a year, I was not allowed to forget my error. Pleading that I was half Italian was of no help whatsoever. The Governor saw an opening and he exploited it.

For nearly two years, my husband, Timothy J. Russert, worked closely with Governor Cuomo as his counselor. I had to get used to the Governor’s seven a.m. phone calls six days a week. (He usually waited until 8:45 a.m. on Sunday mornings.) Sometimes, when my husband was out, Cuomo would chat with me. As a telephone pal, he is a genuine pleasure to know – concerned about others and endlessly inquisitive. It has been fascinating, for me, to witness his spectacular rise to national prominence. Unlike many politicians, Mario Cuomo doesn’t presume that he could bring thousands to their feet, as he did last July in San Francisco when he gave the keynote address at the Democratic Convention. Whether by chance or by design, Cuomo constantly underrates himself.

Take the first of his three great speeches, his Gubernatorial Inaugural Address, when Cuomo outlined his political philosophy – which he dubbed, “progressive pragmatism: — a mix of common sense and compassion based on the notion of the government as “family.” The speech was so moving that even Richard Nixon wrote him a laudatory letter – and reportedly another to the Reagan White House telling them to watch out for Cuomo. Yet, the night before he gave the speech, Cuomo told me, “It’s somewhat convoluted, and some of the ideas are not well thought-out.”

Before his uphill victory in the governor’s race, Cuomo had never won public office on his own. He had lost once for mayor of New York, was appointed Secretary of State by then Governor Hugh Carey, and ran four years later as Carey’s Lieutenant Governor. In fact, Cuomo didn’t run for office until he was over forty.

Many of Cuomo’s views of social justice have their roots in the papal encyclicals published in the early ‘sixties to modernize the Church. Last September at Notre Dame Cuomo gave a controversial speech in which he said Catholics who felt, even as he did, that abortion was wrong would divide the electorate unnecessarily by attempting to impose their views on the political majority.

Whether Cuomo runs for president in 1988, is still anybody’s guess. It’s certain that he loves being Governor of New York. I once watched him approach a startled Alexander Godunov at a restaurant near Lincoln Center. The emigré ballet star was dining alone, reading People magazine and obviously not used to friendly government officials asking if everything was all right.

“What shall I say to him,” asked a girlfriend of mine who was to be seated next to Mario Cuomo at a formal dinner. “Nothing,” I replied. “He will interview you.” Our interview took place at the end of a long day in New York City. The Governor was coatless and had forgotten to each his lunch.

Maureen Orth: An Indian woman sat on the steps of the New York State Capitol last summer beating a drum for three weeks as a protest for Dennis Banks, the then fugitive Indian leader. What does such an intensity of belief mean to you?

Governor Cuomo: People who have a conviction or a mission have a great gift. This woman, beating a drum week after week, thought she was delivering a message for justice. She really honestly believed it, and that’s good. I think if we have had one major weakness in the last twenty or thirty years, it is that we have lost conviction.

I gave a speech some time ago called my “Mrs. Robinson speech.” It turned on a line from a song in The Graduate, that great movie. “Where have you gone, in The Graduate, that great movie. “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you.” What Simon and Garfunkel were singing about was there were no more heroes, no more Martin Luther King, no more John Kennedy, no more causes, nothing to believe it. That’s a terrible, terrible condition. So what does intensity of belief mean? Everything.

Orth: Do you feel there are a lot of politicians who lack that kind of belief?

Cuomo: Some believe in things not worth believing in. Like applause or universal acceptance, which we’re all tempted to believe in. We’re hurt if one guy out of the group rejects the painting, rejects the poem, rejects the article, or votes the other way. A lot of us in this business are ego-driven: we measure satisfaction by whether people approve of us. That puts you into a terrible situation because then you have to keep altering your message to fit what they might want to hear.

Orth: In your Inaugural Address you enunciated the theme of “The Family of New York,” the idea, since widely copied by both Democrats and Republicans, of the state as the family, where the strongest help the weakest. How important is the notion of family politically?

Cuomo: It is the single most intelligent theory of government I can find. You say “family” and everyone understands it. The principle of family is just a neat, convenient understandable way of saying that our society is a disparate, complex, multifaceted one. The government is family because people come together to do collectively what they couldn’t do as well individually – build a road, a school.

I want people out there to understand that you should help people in wheelchairs. There are a lot of people who say, “Let the churches do it, let the private charities do it. I have all I can do to make a living.” If I were to say, “The redistributive function of government is essential in order to achieve a kind of universal equity,” they wouldn’t be impressed. But if I say, “Hey, look, if in your family one of the kids won track medals, and one of them was born to a wheelchair, wouldn’t you ask the kid who won the track medals to pitch in?” And I say, “Now think of this government as a family,” and it makes it easier to communicate.

Orth: What were you attempting to articulate in your speech last September at Notre Dame on the separation of Church and State, politics and religion?

Cuomo: There is a relationship between religion and morality, but you can’t argue that something should be part of the public morality just because it is a religious value. The greatest strength in our democratic system is the freedom it gives people. Any effort that will jeopardize that freedom inordinately is to be shunned. Any attempt to Christianize the nation would give religion a role it’s not entitled to. But many of the questions about where religion ends and public morality starts can’t be answered by formula.

Orth: What about abortion?

Cuomo: This is one of the more difficult cases. The insistence of Catholics that everybody treat abortion as wrong – though it is a view that I as a Catholic accept – is not a wise or fair step to take at this stage. In order to bring your religion to bear on this pluralistic society you have to live your religion well. We Catholics haven’t been able to prove that we reject abortion since we have abortions the same as everyone else.

Orth: Are you attracted to the notion of running for the presidency in 1988?

Cuomo: No. It’s an intimidating thought, a disconcerting thought. I think the question to be answered by an incumbent governor is: will you run again in 1986? If you do, I don’t see how you run for president in ’88.

Orth: You’re perceived as a very hands-on-governor. You graduated number one in your class at St. John’s Law School, but you couldn’t get a job with a Wall Street law firm – I guess because you had too many vowels in your name. As Lieutenant Governor of New York for four years you were sometimes isolated by a quixotic Governor. Does that sense of being an outsider affect the way you govern?

Cuomo: Sure, my whole history has something to do with the policies I make now. I would hope that having been a kind of outsider I understand that situation and am sympathetic to it.

Orth: Your book, “The Diaries of Mario M. Cuomo,” constantly suggest a person torn between doing good for the public and doing well politically for himself. You’ve received a lot of good press. Does it ever seem like hype to you? Do you ever stop to wonder whether you’re in political life for the right reasons?

Cuomo: Yes. That’s why I keep a diary. I ask myself all the time, are you sure you’re doing this to help other people, or are you getting to like this publicity? And I test myself all the time. Maybe occasionally I fool myself, I don’t know. The question is, do you honestly believe that what you’re offering is the best thing you can offer? If so, acceptance or rejection ought not be terribly significant.

Orth: Are you honestly immune to criticism?

Cuomo: No, I didn’t say immune. I don’t like being criticized. When I’m in a crowd of five thousand and one person stands up and says, “You big hypocrite phony,” I take it seriously.

Orth: You seem to operate as if you weren’t going to win; and when you do, you’re excited.

Cuomo: If you’re talking about using all of our energy, resourcefulness to win that election, balance that budget, get through that legislative session, yes do go all out. I like that. The worst thing in the world is wishy-washy blandness. What can be worse than being insipid?

Orth: You’re a fighter, yet you’re not necessarily optimistic.

Cuomo: Excuse me. I think of myself as a striver.

Orth: I was struck by the imagery you used in your book about your childhood, growing up in the back room of the family grocery store, the little boy hiding behind the potato sacks, studying. You had your own little monastery back there. You seem to like to be isolated.

Cuomo: Most of the people I know like their moments of privacy. I cherish them. I like thinking things through. Sometimes I feel things through. And that’s probably what got me in the habit of getting up so early in the morning.

Orth: For someone who cherishes his privacy, was it thrilling to give the keynote address at the Democratic convention before millions?

Cuomo: No, that was intimidating. I didn’t want to do it, and I resisted it. We were convinced the speech was going to bomb; nobody was listening to anybody. They didn’t listen to Jimmy Carter and they were terribly rude to Ed Koch – everybody talking and eating salami sandwiches and walking up and down. And the speech itself – I wasn’t convinced it was a great speech. We gave it an 85. So was I looking forward to it? No. How did it come out? Much much better than anybody on my team thought it would.

Orth: Are you a natural orator?

Cuomo: I’m not terrific with my gestures. I’m not a performer like Ronald Reagan. Even when he doesn’t make sense, he’s effective. If my speeches worked, it’s for one of two reasons: One is that the idea being communicated was a good sound idea that people understand and relate to. Second, I believed the idea. That sincerity communicated itself and people like that.

Orth: You’ve been married for over thirty years. You have three daughters and two sons. Your eldest daughter is a doctor and your two younger daughters want careers. How have the women in your family affected you?”

Cuomo: I remember in the Diaries commenting about my mother at my father’s wake. My mother had been virtually invisible to the world. They saw themselves as partners, but he was the speaker for the family. And then poppa became senile and then he died. We wanted no wake – she wanted three days. She got her way. She sat through that wake and performed like a British Queen. And I remember saying in the diary, why are we surprised? Here is momma demonstrating what she always had – intelligence, class, ability to deal with pressure. But she hadn’t had a chance to demonstrate it.

The analogy is kind of crude but that’s the situation with women in this society. They have an immense capacity to participate but no chance to demonstrate it. So my mother’s experience, my daughter Margaret fighting her way through medical school had an effect. It was tougher on Margaret than on a man. I’ve taught law school, so I know how professional schools operate.

Orth: Have there been other experiences?

Cuomo: I have two beautiful daughters after Margaret. One of them has twice been attacked by the same man. The second time he took a cigarette and burned her on the breast and it left a little mark. We never caught him. That affects my judgements on how I feel about criminal law.

Orth: How important has Geraldine Ferraro’s candidacy been?

Cuomo: She put an end to a lot of stereotypes just by her performance – as tough as a man’s tougher than most.

Orth: Is Matilda your foremost confidante?

Cuomo: Matilda is not just my wife. Matilda is the honorary Chairperson of the Council on Children and Families. She was very involved in the campaign. Is she more important than the Secretary to the Governor? She has more input. I can’t measure what her opinion is worth. Sometimes I accept it, sometimes I reject it, but I always hear it. Sometimes it’s the last thing I hear, even if I have a pillow over my head, I hear it.

Orth: Matilda travels more than you do. Whenever you leave New York, it’s only for a very short time. You’ve never seen Paris, or been to China or Japan. Why is it, for someone who has been so prominently mentioned as a presidential candidate in 1988, you aren’t traveling more?

Cuomo: Always in my life there were things I preferred doing, like teaching and speaking. I preferred representing people who were going to the electric chair to traveling. I didn’t want to travel. I guess that somehow makes me shriveled in my cultural instincts. I guess I’m a stiff. Put me down as a stiff!

Orth: What makes you go for a big risk like running for governor against all odds or giving the keynote speech? You could have given your Notre Dame speech at your parish church, Immaculate Conception, in Queens.

Cuomo: The Sicilians have a great expression: He who doesn’t risk doesn’t reap. And risk – what do I have to lose? I started with zero. When you come from behind a grocery store and a wonderful momma and poppa, when staying out of jail would be regarded as a success in your lifetime, what can you lose by giving a keynote speech? People will say you’re not a great speaker? So what? People will say you’ll never be president? So what? I got to be governor, didn’t I?

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments